Taking in the immensity of Chicago-based Jin Lee’s ‘Views & Scenes’ at the Chicago Rooms of the Cultural Center, one feels an uncanny sense of connection between the built environment, natural life and its rhythms, specifically at a time when people are beginning to emerge from extended periods of isolation, bound by the Covid-19 pandemic. The towering ceilings of the galleries cleave open, bringing into view different layers of the city and its seldom seen habitats through pronounced, slim, vertical doorways that make a perfect accompaniment to the horizontality of Lee’s photographic installations. Multiple series of photographs—Train Views, Great Water, Salt Mountain, and Weed—shed light on the rigidity of our view of the city, pointing not only to the narrowness of our own perception, or of the way we think of places, but also to the artist’s deeply intimate experience traversing the Midwestern landscape between Chicago and Central Illinois.

Stepping into the galleries, the serenity of Salt Mountain and Weed subdues the bustle of crowds from the city streets directly below. Lee begins to direct the viewer to relax and gives us the opportunity to take the time to see things mindfully; shedding semiotics of signs, civic infrastructure or the prettiness of flowers. Something ‘else’ catches the eye. Walking into the second gallery, human figures re-enter Lee’s frame, however indirectly, in reflections or miniscule figures that establish Lee’s appreciation of the city and its citizens. Her ability to pay deep attention while engaging with the nuances of medium in Train Views cures the voyeuristic nature of documentarian camera work. Moving on the elevated tracks of the Amtrak, she reveals the back ends of the city and its people to reconstruct a story of households, landscapes, and trade that is often left unaccounted for and overlooked. Lee’s act of traversing this particular landscape over two decades led to over one hundred images of a place and its communities, without overtly flattening the experience of Midwestern America in singular narratives. In conversation, I am struck by her openness, and perhaps now subconscious Zen-like mastery of deeply questioning and understanding through the lens, how to read a community and its people and conditions, in order to subtly point to their aspirations for a better reality.

The denouement of the exhibition is a series of photographs titled Great Water, that begins to capture the primordial harmonies of Lake Michigan. Ranging from the tempestuous to the tranquil, the nameless experience of the unrepeatable moment of standing before the water reminds me of our interconnectedness—through time, elemental being, and specificity of the experience of a region East of Chicago. Liberated into the infinite and held within its boundary, I’m reminded of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon and the dreams of the landlocked:

“The people living in the Great Lakes region are confused by their place on the country’s edge—an edge that is border but not coast. They seem to be able to live a long time believing, as coastal people do, that they are at the frontier where final exit and total escape are the only journeys left. But those five Great Lakes which St. Lawrence feeds with memories of the sea, are themselves landlocked, in spite of the wandering river that connects them to the Atlantic. Once the people of the lake region discover this, the longing to leave becomes acute, and a break from the area, therefore is necessarily dream-bitten, but necessary nonetheless.”

I spoke with Jin Lee about being dream-bitten, about finding oneself in landscape, and on the particularity of this specific moment in the artist’s career.

PS: Thank you for speaking with me, Jin. First, I was wondering if you intended to present the exhibit with a specific beginning, midpoint and end, given the flow between bodies of work, from one room to the next?

JL: Absolutely. I think because the gallery is comprised of three separate, yet interconnected spaces, and because of the serial nature of my work, I was thinking about each room not only by subject or theme but as a particular kind of viewing experience. The first gallery, to me, is a room of contrasts. Mountains and plants are materials that are not only beautiful but historically rich in meaning. The sublime landscape of ‘Salt Mountain’ meets scientific inquiry in the botanical illustrations of ‘Weed’. The grand and monumental salt mountains are juxtaposed with smaller individual portraits of hidden city plants, like an initial meeting where one begins to recognize things about the other. Also, both series are made on the west side neighborhoods of the city, miles from downtown Millennium Park in which the Cultural Center is located, so this gallery points to a broader awareness of the city.

PS: This show has been in the making for some time, hasn’t it? Are you happy with how the works sit in the space?

JL: Yes, the exhibit was originally scheduled to open in June of 2020 and was postponed three times due to different stages of the pandemic and building renovation. The galleries now have new light wood floors, which really brighten and open up the room. Walking into the space is a breathtaking experience and I feel incredibly fortunate to show work in the new gallery.

PS: It must have been stressful to have a show of this scale suspended for over two years.

JL: When I was given the space, I was excited but also intimidated. The Chicago Rooms on the 2nd floor are spectacular, with 30 foot high ceilings and grand, tall windows that look out onto Michigan Avenue. I thought back to two of my favorite shows here, by sculptors Sabina Ott and Christine Tarkowski, and their incredible installations. The two years of delay fortunately gave me the time to consider how to organize, sequence and group photographs to create connections among the series. I got thinking, in a very subtle way, about particular worlds and a sense of rhythm involved in viewing and scale in space. We decided that works should be hung slightly lower than usual, weighing down the bottom quadrant against very high ceilings. Ironically, I was also concerned about the possible distractions of the busy downtown view outside the windows. But in the end, I came to appreciate the unfolding conversation between the work in the show and the city. It’s an important aspect of the experience of the exhibition.

PS: ‘Salt Mountains’ has been a long project for you.

JL: Yes, the series started back in 2007, when I first noticed a large pile of salt at a city storage site near Western and Grand Avenue. I had just come back from a residency at Ucross in Wyoming, and was missing the landscape of stark mountains. I started driving to the site whenever I had time to photograph the mounds, only to find they would scoop out large amounts to use for removing snow over the winter; it kept changing with the seasons. Salt is a really interesting material that changes color and texture beautifully over time and weather conditions. I loved photographing the mountain form, thinking about the immensity of geologic time, and feeling like a 19th century expedition photographer exploring new land… I respect early American Westward expansion photography, and connect with that complicated history of expansion and colonialism. I’d often think about early photographers trying to figure out how to photograph land as a domain. Being from California, I do have an interest in the idea of the ‘West’. Both Salt Mountain and Weed come from such encounters where I found moments of the sublime, of beauty and wonder while I moved through the city. In the last few years, the city has placed a giant white plastic dome over the salt piles and they are no longer accessible.

PS: How did your transition from the West Coast to the Midwest lead to some of these early acts of locating yourself? Something must have provoked you to take your camera and create your own landscapes in a fairly flat expanse.

JL: In a broader sense, I am interested in making these photographs because firstly, I do like making work about places, and while there are few, sometimes no people, I’m interested in the natural world and the philosophical, aesthetic component of it. My family moved to Los Angeles from Korea when I was 13. I grew up in Korea with four distinct seasons, and the experience of seasonal changes as a marker of the passage of time. It’s been an important aspect of my sense of place and my work. I then attended college on the East Coast and have now lived in Chicago for over 30 years. So, I think my interest in landscape and in forming intimate relationships to the environment, through photography, is rooted in my experience of moving and settling in different places. In my work, I seek to create a sense of connection, intimacy and belonging through an active exploration of the materials and sites around me.

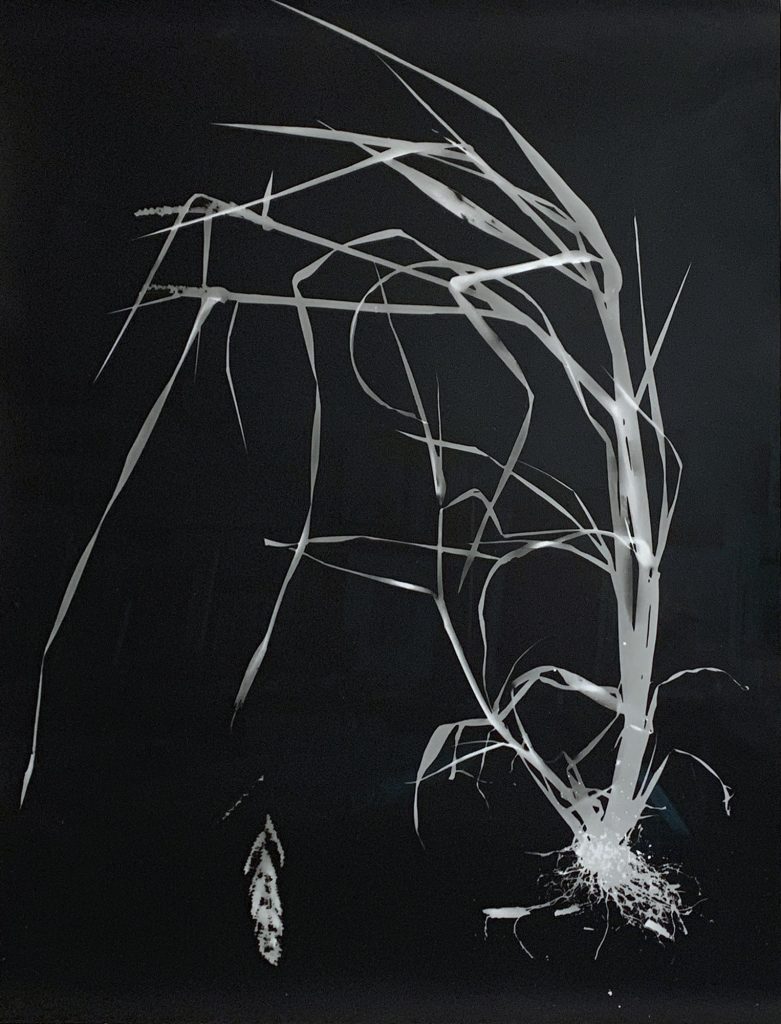

PS: I love the contrast between the photograms from the ‘Weed’ series and your landscapes and couldn’t place why.

JL: The photograms are made from whole plants pulled from the ground and exposed to light on silver gelatin paper in a darkroom. The prints reminded me of Asian ink drawings, but reversed—with white shapes against a black background. To me, the bending leaves look like brush strokes and the glow of the white feels like the transference of a life-form from the plants to light sensitive photographic paper. The photograms are my newest works in the exhibition, and I really enjoyed being back in the darkroom, working directly with the plants. There is a strong influence of Asian art and philosophy in my practice, from subjects seen against flat backgrounds of a white wall or blank sky, to the central theme of impermanence and transience of material worlds.

[Our conversation is interrupted by a stranger who approaches Jin to ask if she is the artist. He introduces himself as ‘Mr.Amtrak’ and explains that he has been riding long-distance trains for over the past few years to help him heal. He shares his phone screen and shows his photographs of landscapes across the West, as seen while riding the famous ‘Empire Builder’ that runs from Chicago to Seattle.]

JL: I love this idea, to think about train rides as a way to get out of oneself. You’re moving through the world at high speed, in a landscape moving forward, to another place. I can see how it can be therapeutic.

PS: Surely! As a young student I traveled most of India by train, but now I’ve come to understand how the train system played an integral role in the British’s scheme to ‘divide and rule’…

JL: ‘Empire Builder’…. the name says it all!

PS: I also think it’s interesting to think of other early technologies that paralleled trains—like the printing press, the first camera trigger, typewriters, morse code…

JL: There’s a book, River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West by Rebecca Solnit, where she writes about the photographer Eadweard Muybridge and the changing landscape of the American West—how the passenger railroad led to the standardization of time, so that the train would leave and arrive at synchronized schedule from town to town. Earlier, time wasn’t exactly linear, nor standardized, but it was moving forward.

PS: Speaking about linearity, could you share how these images were selected from ‘Train Views’? These are views otherwise concealed from the world as often tracks specifically run through the back ends of the city.

JL: These photographs were selected from my weekly two-hour Amtrak commute between Chicago and Bloomington/Normal in central Illinois, where I teach. Moving back and forth on the same fixed track, the rides opened up a whole new world of views and scenes that were not of my choosing, specifically the built environments, and provided me with a different way of making work. I started photographing out of the window as a way to pass time, and to learn to see what I was looking at—the oil refinery, billboards, wind farms, the old Joliet prison tower and limestone quarry where prisoners once worked… And of course the land itself, beautiful and always changing through seasons, weather and depending on the time of the day. I started working on this series in 2014 and by 2016, the election informed the way I viewed and edited the series as a reflection of this ‘present moment’ in the country. Graffiti messages, empty buildings, new constructions, junk yards, self-storage units, an American flag in the dark, lone figures in the landscape.

PS: There’s also something about the facelessness, namelessness of the rider on the train.

JL: It’s like a movie, every train ride is an adventure, with a sense of drama and the unknown. They can feel very cinematic, like so many film and books about the train—The Lady Vanishes by Hitchcock, Murder on the Orient Express, The Girl on the Train.

PS: Speaking of film, there is a length on which you’ve placed your prints on a long table, was that something you decided? There’s a lot of trust in leaving prints face up, uncovered, for people to see.

JL: The west side of the second gallery has dark windows with no wall space, so I decided to have a 30-feet long table built to display a portfolio I’ve been working on. ‘Train View: One Hundred Views’ is a portfolio of 100 prints selected from the series, inspired by ‘One Hundred View of Mt. Fuji’ by Hokusai from the 1830s. The large selection of images allows for repeated views of the same scene transformed by season, weather, and time of day. Certain subjects begin to appear multiple times, including the Joliet prison tower, CITGO oil refinery and Mega Millions Lotto billboards. I find it really interesting to re-look at things over a period of time. Also, I find photographic prints beautiful, and placing prints on the table is how I view and edit my work in the studio. In this way, I think the installation offers a direct experience of the material and the artistic process.

PS: To find when things thematically or compositionally align?

JL: You can take 10 photographs, and luck factors in and maybe one turns out right. [pointing to a single dark image of a blurred American flag at the center of a wall behind the table] When I was photographing this, I realized “This is a really dark moment we’re in”, so taking a critical view of who we are and where we are, historically. There’s a sense of alienation, but you know, only time makes something like that [points to the image emphatically] make sense. There’s the reward of working on something for a long time. You come to understand it differently.

PS: It sounds like you point to an embodied sense of continuity? There’s also the question of what comes into focus in ‘Train Views’. Do you intentionally set the camera for a deeper focus or…?

JL: Often, the foreground is blurry because the train is moving very fast, and things that are closer to the train tend to blur, whereas the distant horizon is more in focus. In this way, there are different registers of sharpness, which I think lends to a different, more dynamic view of the landscape.

PS: So much of your work makes me think of being present as an act of heightened awareness.

JL: Yes, it’s a bit like meditation, which is so hard. I think part of the medium itself is predicated on being fully present, in a state of attentive awareness.

PS: Yes, but I’m also thinking about awareness as active and inactive.

JL: I think that’s what drew me to photography—that practice of both seeking and making things happen, but also being completely open to what is happening. When you’re in the zone while photographing, it’s an entirely different state.

PS: Moving to the final room, what struck me at first was the eye-line in this space.

JL: Yes, I like how the horizon runs through the center of all the images, dividing them into two zones—of water and of sky.

PS: But also in between rooms, the eye-line shifts. In the previous one, the view is dependent on the elevation of the track. Prior to that in ‘Weed’, the camera is low to the ground, and then the gargantuan scale of the salt mountains where you are looking up at them. We are constantly being moved through different vantage points.

JL: The vantage point is critical to photography. It creates a specific view of the subject and also locates the body in relation to the subject.

PS: And this is an ongoing body of work?

JL: Yes, I’ve been photographing the lake since 2005. It is so central to our sense of place in this city. Like even if you’re not at the lake, you still feel its presence and know where it’s located in relation to where you are.

PS: Yes, it seems the lake became a huge source of relief for people in the course of the pandemic.

JL: I’d meet friends at the lake all the time and swim in the summer to cool down. But I also go there to be alone with my thoughts and feelings. I began to notice other people there doing the same thing, taking refuge and connecting to the water. I think about how the lake holds space for everyone and everyone has their own relationship to it. Whether they’re fishing, reading by the water, or just hanging out having a smoke or a drink, it’s always cooler by the lake and it’s free to all.

PS: Yes, it’s an open resource.

JL: Yes! Did you know the Cultural Center is called the ‘People’s Palace’ because it’s also free and open every day? I love that this show is in a free museum, where people can come anytime to see art, listen to concerts, view the architecture, or just to rest.

PS: Also, thinking about how this reinserts you, the artist, into the city. I think it’s really important given how much museums are struggling to find their relevance today. Going back to the lake, which is technically right behind us, across the park…

JL: I hung a large photograph of the lake on the eastern wall between these windows to point to the unseen lake, beyond the park. There is only one picture of a person in the gallery—of a young girl looking out at the water with long black hair flowing down her back, on the opposite wall. I loved how she seemed so contemplative. She’s doing what we’re talking about—being in the landscape, immersed in the moment. The photographs also give you a clue as to where I am. They’re all taken from a single location on the South Side. I felt that it was important to center myself, in order to study the immensity of the waterbody more closely. There are clues about the location in a few of them… If you look closely, you can see Indiana [running her finger along a horizon line] and pumping stations on the horizon, on a clear day.

PS: Do you also think, in the process of capturing these images, that the water mirrors or influences your mood?

JL: That’s so interesting because when I was editing these images, I started to think about each photograph as a different mood, a different state of mind. Yes, I think there is an exchange. I respond to the mood of the lake and also become aware of my own interior state when I am by the water. The lake has infinite variations, and that’s what makes it so great.

PS: I often wonder about how our perception of an image essentially points back at us. Like can there ever really be an objective read of an image…my favorites are where the horizon line vanishes.

JL: Yes, I definitely identify with many of these moments.

PS: Are these shot on a specific film?

JL: All of the lake photographs are shot with a medium format film camera. When you get close to the photograph, the image begins to fall apart into a field of film grain, which I find really beautiful.

PS: I’m wondering as someone shooting on different formats; large, medium and digital, are you concerned at all about the ‘legitimacy’ of the image?

JL: They’re very different processes, so I don’t think it matters in the end. When I work with film, it’s a different process because you may not see the image for a while until the negatives come back from the lab and are scanned. There’s a waiting period, of almost forgetting what you photographed. When I teach darkroom photography, my students enjoy this the most because they are so used to the instantaneous. You don’t even know if you have a picture and there’s a feeling of joy when you do see it, because you worked hard to capture that moment. There’s also the tendency of a picture always being more or less than what you might have thought it was going to be, so the element of surprise comes in. There’s a sense of traveling back in time to when you made that picture, of recollection. It just takes more time and work, which is part of the reward. I think it teaches you patience.

PS: Yes, there’s something about sustained attention the work demands—on both the making and receiving end, in the perception of your images.

JL: Everything comes down to the material. I think in film so I am partial to it, it’s become my vocabulary. But there are some images I make with my phone camera if the need arises, so I have to use the tools that work for a particular moment, you know? Tools don’t validate the image but different processes produce different relationships and experiences. I do think my work is about creating relationships to subject matter and to place. Like you said, your perception echoes back at you. The tools become part of a larger set of experiences.

PS: So the act of forgetting the image is also part of the process?

JL: Yes, I think of the photograph as proof that you were present, then and there. Exactly.

PS: Krishnamurthi once implied something like, how does the experience of memory point past itself, towards the eternal. I was thinking about this a lot here as these images of the lake feel so timeless, and yet so time and place specific.

JL: I wanted this to be the final room for viewers to get to that place where there’s an open-ended sense of place and time, that is specific to the particular states of the lake. It took me a long time to put together this series. Every series started with questions, “What is this experience? What does it mean?” I know that things I see around me have meanings, but they are revealed to me in time, over a long period of repeated viewing and renewing my relationship to them over and over again. It’s a question of going back and looking again, even more closely, each time.

Jin Lee’s exhibit ‘Views & Scenes’ is on view until August 7th at the Chicago Cultural Center’s Chicago Rooms, 2nd floor north. More information is available here.

Pia Singh is an independent writer and curator. Born in Bombay, India, and currently based in Chicago, she has organized several exhibitions and public programs since 2010, recently founding by & for (2020), a solidarity initiative that aims to bring together artists, curators and art professionals in support of community-run organizations. Her research investigates community-engaged arts practices through the frameworks of Contemporary Art and Design Thinking, to challenge hierarchies and structures within and outside of which artists form a set of improved conditions in communities, through artistic and collaborative research.