Projections of an opaque body of water, rippling with rays of sunlight, fill the east gallery of the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s (MoCP) newest exhibition, In Their Own Form.

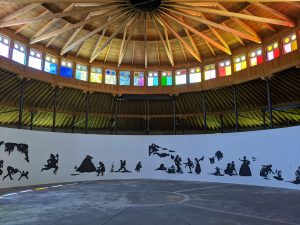

This film installation Passage, by South African artist Mohau Modisakeng, is presented cinematically with echoing audio of splashing water, a ship’s bell, and docking boats. The sonic experience is enhanced by the large-scale tryptic of three black figures in motion that monumentally tower above the viewer. Each visual signifier presented — three sinking white boats, figures in antebellum-era clothing, submerged bodies contorting in distress, a clasped black whip — are shown from an aerial perspective in a manner that abstracts the components of the image into lines and shapes. Over the duration of the film, the composition of the projections shift to resemble a ticking clock, a coffin, or even a curled fetus in the womb. Whichever narrative emerges out of the viewer’s subconscious, Modisakeng’s tantric images conjure up historical references to the Atlantic slave trade by interrogating water’s relationship to black bodies.

Natural bodies of water and spacious environmental landscapes feature prominently across the photography and moving imagery on view in In Their Own Form. The exhibition’s curatorial vision pays homage to the ancestral lineages that came before our present moment in time. “Water in Afrofuturism is both life giving and erasing in terms of the Middle Passage, and in African spirituality,” said curator Sheridan Tucker Anderson, MoCP’s Curatorial Fellow for Diversity in the Arts.

Whether in front of the swirling waves in Teju Cole’s Brazzaville or along the ocean shore of Alexis Peskine’s euphoric portraits, Black subjects in the exhibition are dynamically placed in the foreground and active in their positionality to mother nature. It is as if they are metaphorically reclaiming agency within the disempowering narratives that circulate in the world’s public imagination regarding the black experience–from 21st century immigration politics for people of color to canonized American history that designates the Middle Passage as the starting point of history for African-Americans.

While In Their Own Form certainly honors 21st century understandings of Afrofuturism’s foundational aesthetics through expressions of Pan-Africanism, technocultures, and Black liberation, Anderson chooses to conceptually approach the exhibition from a unique historical perspective that harkens back to nineteenth century abolitionist Frederick Douglass—a scholar she describes as “proto-Afrofuturist.”

“I had been doing research on the history of photography, specifically as it pertains to black Americans, and I came across an essay by Henry Louis Gates where he explores Frederick Douglass’ connection to and affinity for photography,” said Anderson. According to Anderson’s curatorial research, Douglass was not only the most photographed American of his era, but also strategically used photography as a political tool to capture the humanity of black people in resistance to caricatured representations of Blackness. “[This approach] allowed for a more historic approach to the Afrofuturist movement. I wanted to emphasize that afrofuturist ideals had existed long before Dery ‘coined’ the term in 1993.”

The gesture of conceptually moving backwards in time in an effort to activate the historical memories of antebellum-era ancestors in a 21st century contemporary moment, is what makes the curatorial strategy of In Their Own Form inherently Afrofuturist. It engages with a warping of time and space that is distinctive to the Afrofuturist philosophies of seminal writers like Octavia Butler and film’s like Marvel’s Black Panther.

While Afrofuturism often appears across mediums in visual art, literature, and music in popular culture, In Their Own Form is medium specific. There is a keen attention to the ways in which the photographic medium has served as a politicized reframing device to center black subjectivity–much like Frederick Douglass did centuries ago.

The exhibition is not only inspired by the plight of African-Americans in the United States, but also traditional African cultures. “The [natural bodies of] water referenced throughout the show are an intentional choice that make a nod to both traditional African spirituality and Afrofuturism,” said Anderson. This global approach successfully links contemporary manifestations of Afrofuturism to their original diasporic roots.

Alexis Peskine’s photographs on view showcase reinterpretations of Senegalese talibe children–youth who gather money on the street–by portraying them confidently wearing stylized uniforms with ready-made helmets, belts, and clothing along an ocean shore. In the photograph Aljana Moons, two boys regally sit in a horse and carriage in a manner that shows agency and pride in their environment. The horizon line behind them falls beneath the figures and fills the bottom quarter of the composition, further allowing them to dominate the natural landscape in which they are immersed. While more dystopic compared to Peskine’s work, Fabrice Monteiro’s images in the series The Prophecy reimagine present-day ecological issues in the most polluted African nations. In his image Untitled #2, for example, an elongated figure who is part detritus and part human emerges from the depths of a rocky ocean shore wearing a gown of black plastic trash bags, feathers, and cowry shells. Although his characters are made of discarded materials, they serve as superhuman creatures that have flourished despite the environmental catastrophes surrounding them.

In Their Own Form locates Afrofuturism from the perspective of reviving ancestral memory through futuristic modalities. Yet the thirty-three works on display more convincingly understand our natural world–the ocean, land masses, sand–as the connective tissues that have consistently linked both global and continental experiences of the African Diaspora.

_

Featured Image: A still from Passage, a 2017 film by South African artist Mohau Modisakeng. The black-and-white image is taken from an overhead view and depicts what appears to be a woman in a black dress with white fabric showing slightly from underneath the top skirt. She is barefoot and laying flat in a small boat that has a white interior. The boat fills the center of the image, with the head of the boat pointing upward. The water is dark, and a spot of sunlight shines in the top right corner, reflecting off the water. She holds a black whip over her head with her right hand.

Sabrina Greig is an art critic in Chicago, originally hailing from New York City. She received her MA in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on representations of the Black diaspora in pop culture, fine art, and gentrified urban spaces. Sabrina is a current curatorial fellow at ACRE projects located in Pilsen and has curated shows at the Haitian American Museum of Chicago as well as the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary work has been published in Fnewsmagazine and Bad at Sports. For more, visit her website.

Sabrina Greig is an art critic in Chicago, originally hailing from New York City. She received her MA in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on representations of the Black diaspora in pop culture, fine art, and gentrified urban spaces. Sabrina is a current curatorial fellow at ACRE projects located in Pilsen and has curated shows at the Haitian American Museum of Chicago as well as the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary work has been published in Fnewsmagazine and Bad at Sports. For more, visit her website.