To schedule our interview, oral historian Rae Garringer once again needed to use their phone as a hotspot. The day before, Hurricane Helene had ravaged the Florida coast, bringing with it flooding across central Appalachia and internet and power outages to Garringer’s home in southeastern West Virginia.

On the day we spoke, their power restored and their family safe, they shared an hour of their time with me before transporting supplies to southern Virginia, which had been hit harder by the storm. Relationships in these parts of the country are—by mutual necessity—of a different charge. To overcome time and distance, queer relationships here may require an even higher voltage. At least this was Garringer’s experience after nine years away from the Allegheny Mountains they grew up with. After going to college on the East Coast and living in Austin, Texas, Garringer moved next door to their family’s sheep farm and returned both to the feeling of home–“a calm rootedness” they had never experienced before–and to a deep sense of isolation.

Where were the queer people? Where were their stories, ones that didn’t end in death? What could life look like, for Garringer themself and for other queer people living outside cities?

To answer these questions, Garringer began to interview the queer people they knew elsewhere in Appalachia. In 2014, they crowdfunded a summer road trip; other queer people in rural areas and small towns across the country (and beyond it) also longed for connection. What started as a borrowed recorder, a flip phone, a paper atlas, a “used Subaru Forester with over 160,000 miles on it,” and sheer will led to a way. To date, Garringer has documented queer stories across 21 states from people as young as 19 and old as 81, people who work at manufacturing plants, who manage farms, people who are political organizers, drag queens, authors. Country Queers isn’t a “passion project” or “hobby,” Garringer tells me in our conversation. “It grabbed me and wouldn’t let go.”

While my own boots are planted firmly on Midwestern ground, and I dream only the occasional dream of leaving for desert country, this vague sense of relation between my region and theirs has been nagging at me for years. After talking with Garringer, I realized we both experienced a form of existential claustrophobia triggered by one smothering national narrative: to succeed, to have potential in the first place, we’ve been told in countless ways that we must leave the place we call home for the “greater,” coastal place; the bigger, more cramped city.

Well, maybe we’re both here to tell anyone who’ll listen that we stayed, we returned, and look: these seeds can’t grow anywhere else. When I say seeds, I mean stories…or maybe I mean relationships—what’s the difference, really, in a life? Maybe in the larger community of Country Queers Garringer would be best described not as an oral historian but as a farmer, a gardener, a seed collector.

Now after more than a decade of collecting for the ongoing multimedia project, which includes a podcast, Garringer has assembled photographs, interview excerpts, and reflections on the at times arduous journey into a book, Country Queers: A Love Letter, released in October by Haymarket Books in Chicago.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and flow.

Amanda Dee: The Country Queers project has had and continues to have permutations online and in person, but you’ve always dreamed of a book. Now that you have this book, what does it mean for you and the project?

Rae Garringer: I’ve been thinking about it a lot this week. I didn’t have power for six days over the course of Helene, and I grew up in very rural West Virginia where we would lose power all the time, for days and weeks even. It’s just the reality of infrastructure and the power grid in rural Appalachia. I grew up without TV. I grew up mostly pre-internet, or pre-internet in rural areas, and books were my total connection to the world outside of the farm where I grew up and outside of these mountains. Both through fiction and nonfiction. I love books, I love the slowness of them, I love being able to hold something in your hands that’s not a screen.

And so I’m really excited for a few reasons. One is that it feels like the arc of this project, this original dream that I started imagining in 2012, probably 2011, definitely 2013 when I started recording interviews—a beautiful book with full color photographs of people in their places—it’s coming true. But then, at the same time, I’m really excited for there to be a way for other isolated rural queer and trans people to spend time with these stories that doesn’t require internet connection, that doesn’t require electricity, that doesn’t require cell service, which is the reality for so many rural people still.

AD: And it becomes an object, or an artifact, in your own home.

RG: Totally. It’s interesting ’cause the podcast, it can come into your own home through speakers, through headphones—and social media, of course, is in people’s homes—but to have it on a shelf and be able to be like, these stories of all these real queer people are in my house, even when I’m not, it feels different.

AD: I mean, when you think of history, you think of a library, and to have a physical marker in your library that these stories—these people—were here, it feels kind of profound.

RG: It really does.

AD: You’ve also talked about how queer elders are often missing from these histories, how you often struggle to find them for the project, in part because of the AIDS epidemic and also because there’s a generational difference for a lot of older queer people to be out and proud in general, especially in small towns and rural areas.

This project documents a lineage that not only says queer people are in these parts of the country, but that they’ve always been here, so I’m curious about your own lineage of storytelling. In the book, you have a long list of acknowledgments of people in your community and you mention some musicians like Hazel Dickens and Amy Ray and authors like Dorothy Allison. Are there storytellers or stories that first imprinted on you or that you’re returning to now?

RG: Well, it’s funny because the first thing that comes to mind for me actually is not about queer stories, but people sometimes will ask me, why did you choose oral history?, because it’s not something I studied and I don’t remember the first time I encountered oral history talked about in that forum. But what is true is that I grew up in rural West Virginia public schools. My parents, my family, are not from this region before my generation, but I grew up immersed in a very rural mountain place. That slow storytelling in person, on a porch, in the barn, is kind of the way of these mountains, or it has been for a long time. I think this format of sitting down together somewhere, often outside, and really talking for hours is a very Appalachian way [of storytelling].

That’s one thing I think of, but then I think in a queer elder sense and queer storytellers, like Dorothy Allison. I read Cave Dweller when I was in high school in West Virginia before I knew that I was queer, and I very much still remember the hints at queerness and being like, huh, this is interesting. Then once I got to college, my first queer love would leave me Dorothy Allison poems in my dorm room. It’s unfathomable to me that [Allison] let me just come to her house and interview her without knowing me, and she’s in the book.

Since then, I got to have some conversations about queer oral history with Randall Kenan, before he passed away, when I was a graduate student in North Carolina. I hadn’t known his fiction, which is full of rural, Southern, queer history, before then. There’s so many other queer fiction writers from the South whose work has been really important to me. Fenton Johnson, Silas House, my friend Carter Sickels was the first, that I knew of, trans Appalachian writing rural queer fiction. Novels have been a place that I’ve gained a lot of support.

And bless Amy Ray. I probably shouldn’t say this on the record, but I think of Hazel Dickens as a country queer elder. She might not have been queer in practice, but I feel like she’s such an icon.

AD: Have you read Dorothy Allison’s essay on writing place?

RG: I haven’t.

AD: I’ve returned to that essay so many times thinking about my own writing about the Midwest. Knowing how you feel about Dorothy Allison…you might be very into it.

RG: I’m kind of obsessed with her. I think about this all the time, when I got to interview her in 2018—it’s in the book—she said, “I like writing, I don’t like publishing. I don’t like becoming an icon. It’s uncomfortable.” I also love that she told me directly to my face that she hates that.

AD: It reminds me of how, in the book’s postscript, in hermelinda cortés’ interview with you, you talk about the discomfort of becoming a semi-public figure with this project. Maybe this is a good time to talk about your background in political organizing.

I’ve done some oral history as well, and I think what draws me to it compared to, say, journalism is it feels more like a conversation, or at least the way that I think good oral history does, where you have to give a little more of yourself when you’re listening to someone else’s story, where journalism feels more like, I’m coming here, I’m doing this interview, and then we’re done. Oral history feels more intimate. I think part of it is that oral history feels more like an attempt to be a collective format. And it also often fails in that way, as you know. I’d be curious to hear more about your connection to political organizing and oral history as this imperfect collective medium.

RG: To start where you started, I’m a hermit, I’m a recluse, I’m an introvert. I really love to be on the other end of the interview process. I think part of what happens for me is people will be like, I’m such a fan of your work!, and it doesn’t feel like mine. This is a collaborative process and it doesn’t work at all without the people who have agreed to share their stories with me, especially the 40 or 50 people I talked to in the first two years who didn’t know me. I had no experience. I had nothing to show them that I knew what I was doing or was worth trusting. And they just opened their homes and their lives to me with so much generosity and so much vulnerability, and that’s what made this project. And all the people who donated and supported this project and my poor friends who have listened to me fret about this for 11 years, constantly. So that’s one piece.

And then, I hadn’t really thought of it like this before, but in the extended conversation I had with hermelinda cortés, who’s on the podcast editorial team, she pointed out: You didn’t go to an oral history master’s program before you started this, but you were connected to all sorts of Southern and Appalachian movement spaces where a lot of the ethics of [and] the importance of communities, particularly marginalized communities, having agency and control and say over how they’re represented, especially when they’ve been documented from the outside for so long, is central to the organizing framework. Storytelling is a central Southern organizing component, like listening circles and connection through story.

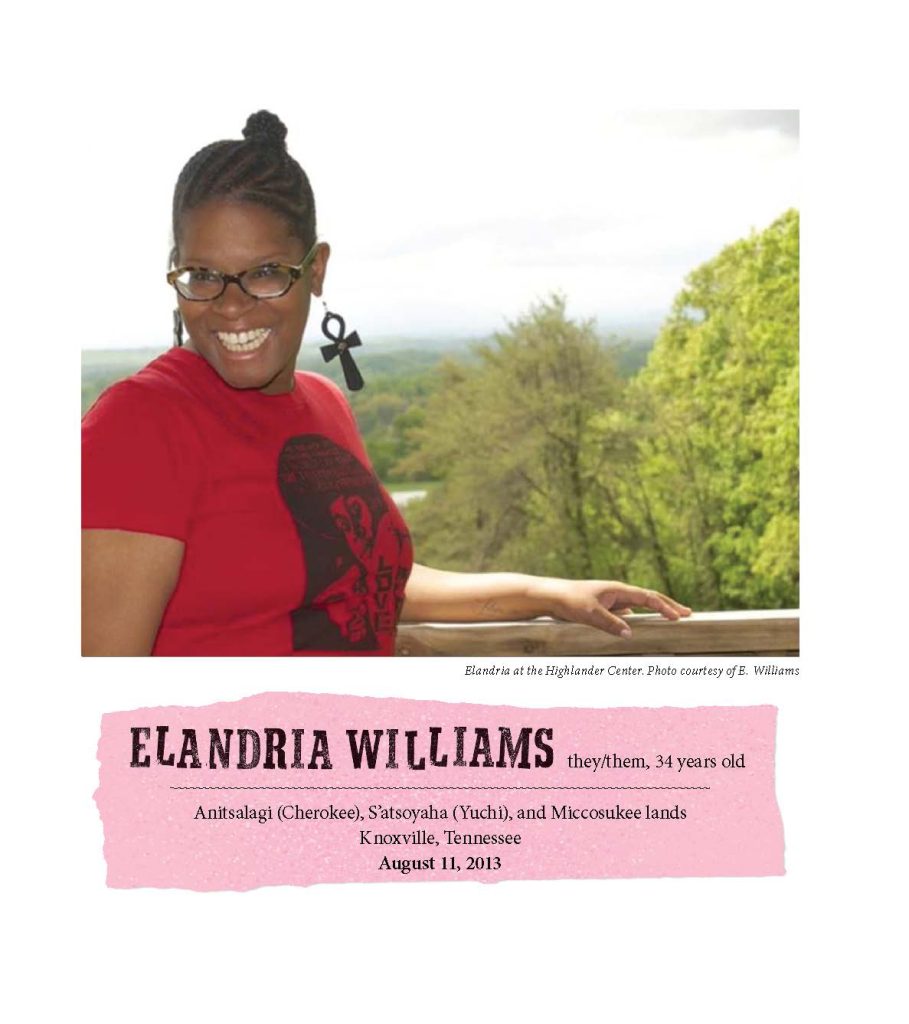

In the beginning of the project, I was under 30 and a member of the Stay Together Appalachian Youth (STAY) project, which is a network of young people across the central Appalachian region. That organization, in some ways, was brought together by three people in much older organizations in the region that all had some youth work, which were the Highlander [Research and Education] Center in East Tennessee, Appalshop in eastern Kentucky, and High Rocks in West Virginia. Appalshop, I don’t even know how, is this over-50-year-old media arts center in eastern Kentucky that comes out of this history of mountain people needing to be able to tell our own stories based on the incredibly problematic documentation of the region during the War on Poverty.

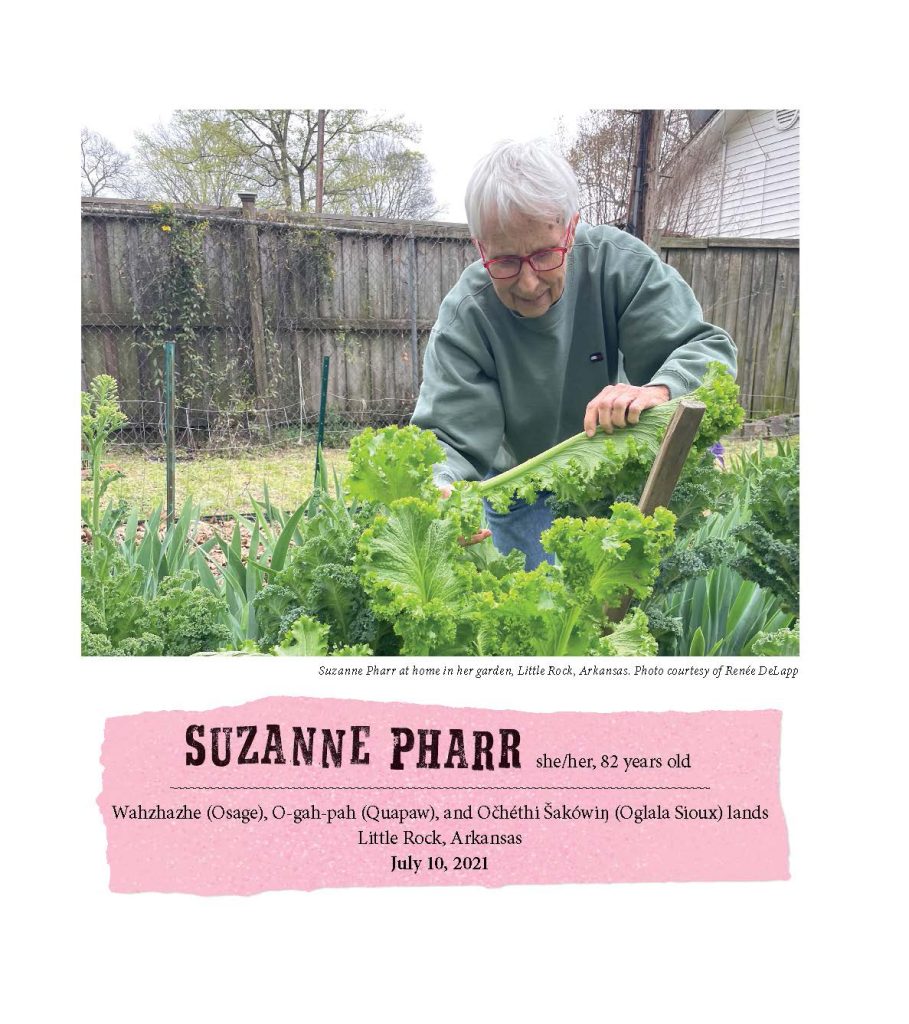

So, in many ways, my training for this project was not through an academic oral history lens, but it was through being part of spaces within Southerners on New Ground, or SONG, which hermelinda and Suzanne Pharr, who wrote the foreword [for Country Queers], co-facilitated. SONG is a space for rural queer Southerners to talk about our homes. From across the region, we would, and they continue to, hold these autonomous spaces for young people in central Appalachia. Cultural organizing is so ingrained in almost all the work I’ve been a part of in Appalachia.

The other thing I’ll say is that before I started Country Queers, I didn’t have a social work degree, but I did a lot of that kind of work with young people, in dropout prevention organizations, in shelters for houseless youth and young adults. I think being able to create a space where young people—often in crisis, and many of them queer—felt safe to talk to me about what was happening, that was training that supported and influenced my approach and my process in this project.

AD: I think your training makes a lot of sense for your attraction to oral history. I’m of the mindset that you can’t just go and get a degree in oral history or even journalism and be good at it, at least that’s not true of the people doing this work who I respect. You have to be a sensitive listener, you have to be listening for the right things, and you have to be able to understand that you’re working with real people, right? You don’t just want to get the good juicy story. You want people to feel like they were heard. Really, at the end of the day, that’s what you give back to someone, besides documenting their story.

RG: There’s one more thing I’ll say on this. There’s a historian based in North Carolina who I really admire named Cynthia Greenlee, and we have worked together on an oral history project and podcast through the National Council of Elders. In a training she led, she talked about how she came to oral history later, after a long time as a journalist, and how she had to really shift her approach. As a journalist, sort of like what you were saying, she would show up with her list of questions, her focus for the story, her plan, and she realized as an oral historian that it was a lot more like porch sitting. You show up to have a conversation in a slow way and to collaborate with someone on where that goes. I think about when she said that quite a bit these days.

AD: In Country Queers, after each interview, you have your commentary, reflecting on that interview and on your own evolution as an oral historian. You also include what you were going through personally at the time, the material reality of your situation as you’re doing this work, which I felt was almost if not as political as these stories you’re telling.

RG: It is important to me for people who are not based in rural places to understand that there’s a different level of challenges to doing media work, to doing documentary work, if you’re actually in a rural, economically depressed region with little infrastructure while you’re doing it. I don’t feel like I hear that being acknowledged enough in national media landscapes. Just getting around in rural spaces takes so much time. Basic infrastructure challenges that are the reality for so many rural people are absolutely a part of the story of this project. Even in training for how to do this kind of work, or the kinds of funding that friends of mine who are doing incredibly brilliant work but are based in LA or New York can get, [it is so much different]. There’s funding opportunities for lefty, queer, and trans people working in cities that’s really hard to find in a state that’s run by coal companies.

AD: I want to pivot to the connection between the South and the Midwest that you bring up in your preface. You write, “It becomes clearer to me every day that small towns and conservative cities across the South, Midwest, and West are the new front lines in the battle for queer and trans liberation.” I’d love to hear you talk more about this connection.

RG: What I’m trying to get at here is the level of anti-trans legislation introduced this year alone is unlike anything that’s happened in such a coordinated, national way in the 11 years that I’ve been gathering stories. It’s unique and it’s dangerous and it’s terrifying. Clearly all of this, Trumpism, Project 2025, if implemented, affects queer and trans people across the country, including in cities and coastal cities, but the ways in which this has been sweeping the South, the Midwest, and the Western states not on the coast is noticeable. I follow Erin Reed, who’s doing incredible work tracking the anti-trans legislation across the country with these risk maps, and it’s incredibly clear that there’s a different thing happening for those of us who aren’t on the coasts.

I also think there’s a really different thing happening in states that are predominantly rural. While West Virginia borders some states that have significant cities, like D.C. for example, the largest city in the state is less than 48,000 people. There are a lot of rural places in Georgia, but they have an Atlanta; and there’s a lot of rural places in North Carolina, but they have a Durham, they have a Raleigh. There are states where we don’t have a progressive city with a concentration of queer and trans organizers who are ready to go. We just don’t have the kind of infrastructure and resources that tend to be in major cities, like the funding, the organizing infrastructure, the networks and communications and media infrastructure. We’re sometimes in our second, third, fourth year of having Pride celebrations at all. The kind of backlash people are facing, it’s different. These attacks, and not to mention the increased rise in organized white militias across a lot of these places, too–the link between Proud Boys targeting drag performers, that’s happening across the South, Midwest, and West in a way that’s not happening in the same way on the West Coast, on the East Coast, in the Northeast.

AD: The stakes are different.

RG: Absolutely.

AD: Across the interviews there’s this refrain about living in the country, which stuck with me, about the need to stay and mediate conflicts with the people you live with that contrasts a place where you can just get a new job, maybe, or you can just meet other people, find a new relationship, where there are more people to choose from, at least in theory anyway. This came up in E.’s interview when they say that being country queer, to them, means “you can’t leave your folks at the door.” Did you notice this theme, or refrain, as well while you were collecting interviews?

RG: Definitely. And it’s something that I feel very much in my own life. I think E. said it really well in their interview. I love Crystal Middlestadt, who talked about this as someone who mostly did have experience in urban queer scenes and then found this different kind of need for each other in a small place really refreshing. It’s a real beautiful strength that a lot of country people have, and that’s not to say that there isn’t all sorts of conflict and violence and horrible things happening in our communities, of course, and all sorts of people who don’t get that kind of generous treatment, but I do think if we’re going to make a generalization, in my experience, you just can’t throw people away in the same way if you live in a rural county or in a town that has 2,000 people total. It doesn’t work.

I think of all of my central Appalachian friends who are organizers and very political. If there’s a fight about the prison proposed to be built in your small county—like in Letcher County, Kentucky, there’s this federal prison that they’re pushing through and there’s a lot of local resistance—people’s own families are divided about it. You are going to see the people that you disagree with politically on maybe everything at least every week, if not every day, depending on where you work and what your relationship is to being in town. And I think that does change how we have to relate to each other.

I have all sorts of neighbors who I’m sure I disagree with on literally everything politically. And I know, from this week, that when the power is out, they check on me and they come over. We see each other. We know that we don’t agree, and we’re going to make sure that we have water. We’re going to make sure we can get out if there are trees blocking our roads. I’ve been thinking about this a lot this week. I’m so glad that we have, nationally, a framework for mutual aid. I think about Suzanne Farr, who’s 85 and grew up in rural Georgia in the ’40s, and talks about how mutual aid is just how country people have always survived. Many people here still don’t talk about it as “mutual aid,” but you just have to live that way to live out here. It’s a really beautiful thing about a lot of rural communities, and I don’t think that gets lifted up in national media very often.

AD: I think it speaks to this long-standing myth that the book and these stories counter. This idea of the South or small-town America as a repository for “backwards ways of thinking.” Cities up North? It’s fine. On the coast? It’s fine. As if that’s where all the progressive views of our country live. Even in saying this, I’m starting to think about how, in so many of these stories, people move all the time, even people who live in a place for most of their lives. There’s this false binary of North and South or rural and city, when everyone’s passing through these places. Some people might live in a city and then return, like you and so many others have. These stories show the movement that counters this idea that here is where that type of person lives in our country.

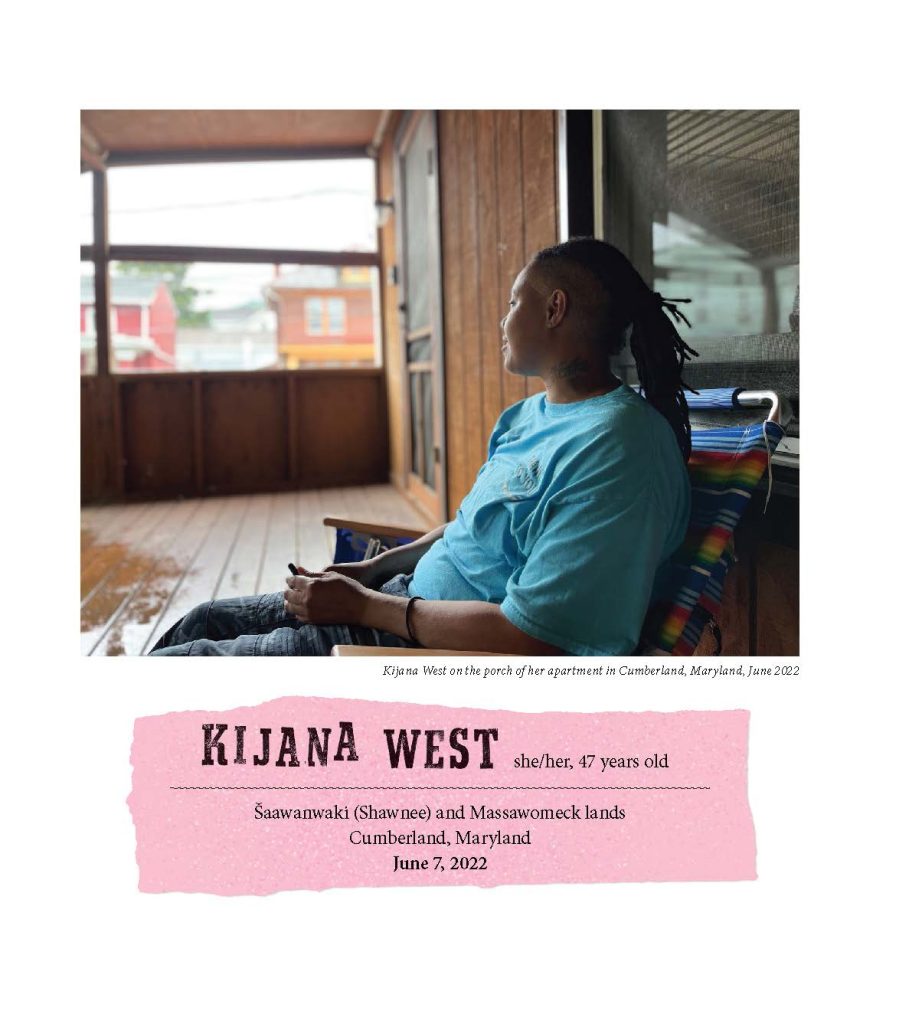

RG: I really think about Kijana West’s interview when you say that. I learned so much from that interview because Kijana was born and raised in New York City but has deep family history in the mountains of western Maryland where she spent summers with her family, Black Appalachian people who’ve been in this place for generations. It feels very much like home to her. She ultimately moved to Maryland from New York City after an entire life there.

Speaking of my own evolution from earlier on in the project, I might not have interviewed someone who’d spent most of their life in New York City until that year. But Kijana’s story adds so much about that conflict, the complicated ways in which so many people are connected to rural spaces, even if they’re not in them, and also the movement that you’re talking about that rural communities are made up of. People who’ve grown up there their whole lives and never left, people who’ve left and come back, people who’ve moved there from a totally different part of the country or the world. That false binary is really strong. I mean, in so many ways, national narratives try to simplify things in a way that erases all of the nuance.

AD: In the preface you say, “We have always made a way out of no way.” And that’s what happened with this project, where despite fear and anxiety and a whole lot of other feelings, not having enough resources, you found a way. How did you grapple with knowing that you needed to do it? Where were you drawing from to get Country Queers going versus this pressure that you started feeling, after you were involved in the project for a while, to do it in a way that felt like you were doing it right by the people involved? To take a step back and be like, no, I need to be more intentional about this?

RG: People are like, oh, it’s a passion project! I’m like, no, this has been an obsession my entire life. This was not a hobby. It grabbed me and wouldn’t let go. To be totally honest, it’s added so much stress to my personal life. I didn’t know how hard this would be when I started it and had this fantasy of a book. But I was super isolated. I was living back on the driveway I grew up in, an hour outside of a town, working in public schools that I’d grown up in, not being able to be out at work. I had a lot of rural queer community across the central Appalachian region through STAY, but not locally in the part of West Virginia where I lived at the time and live again now. I felt desperate to be like, okay, I’m so happy to be home. My chronic illness is so much better since I left the city. And also, I’m really isolated. I don’t know how to make this work. And I’m starting to realize that there are people here who’ve been doing it longer and I want to learn. I don’t think if I had needed it so bad personally that I would have done it, which is maybe selfish to admit, but it has been so challenging in so many ways that if that weren’t true, I don’t think I would have kept going as long.

I do think you’re right, that at a certain point I started to be like, oh, whoa. People really want this. Other country queers are asking me to come to far west Texas from West Virginia, which is a very long way, because they’re like, we need this. And then, I was like, wait a minute, this is really complicated. People are telling me stories full of trauma, full of things they’ve never told people before, that I’m recording and feel pressure to share. And then of course, all these other things came up around who’s self-selecting and how this project, as a whole, is interacting with race in rural contexts and with histories and the presence of racial terror and genocide–all these really complicated things emerged later. I learned how to do this work through doing it, and so I didn’t know all of the complexity of it at the beginning.

AD: Following up on that, if someone were to want to start a storytelling project like this, or feel like they wanted to connect to other people through oral history, do you have any wisdom you’d share with them?

RG: There are things about how this project has evolved in this ongoing rambling way that are beautiful, but I would give yourself a goal, like we’re gonna gather 30 stories and then see where we’re at. I think that some boundaries around what the thing is at the beginning could be really helpful.

There’s a huge section of the book that’s just called “The Overwhelm,” which is probably also the most amount of years in the project. I mean, hindsight is 20/20, but if I could have found one other person who was equally as obsessed or even, like, partially as obsessed as I have been about this project who wanted to help me think through it along the way [it would have been helpful]. [Although] the editorial team for the podcast has really become that even outside of the podcast, but between 2013 to 2020, when they came on, was a long time. There were a lot of other people who helped shape it and who I had conversations with and volunteers and all sorts of things, but I think having a team, even if it’s one person, and having a narrower focus, whether it’s regionally, whether it’s how long you’re going to gather things, I would recommend all of that.

AD: Is there anything else you want to add about the book or the project?

RG: To bring it back to where my brain is, with this devastation across Appalachia after Hurricane Helene, it’s a weird hard time to try to promote a book while this region that is my home, that I’m so deeply in love with and fiercely protective of, is in such intense unfathomable crisis. All of my central Appalachian country queer community are actively coordinating mutual aid across the region right now. I think country people need each other in good times, but in times of crisis, often we’re literally all we’ve got, our neighbors out a holler that’s cut off from the rest of the world.

Rural Disaster Relief Support Recommended by Rae

- Rednecks Rising (supporting western North Carolina): @chelseawnc on Venmo

- Knoxville First Aid Collective (supporting East Tennessee): @firstaidcollectknox on Venmo

- Care Collective of Southwest Virginia (supporting southwest Virginia): @carecollectiveofswva on Venmo

- Appalachians 4 Appalachia Hurricane Helen Response Fund through Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky

Find Country Queers: A Love Letter through Haymarket Books or wherever else you borrow and buy books. Listen, view, and learn more about the oral history project here.

About the author: Amanda Dee is a writer, documenter, and apparition of the Midwest. She’s on staff at the literary journal TriQuarterly and, in a past life, was the editor of an alt weekly. Photo by Momoko Fritz.