I entered the exhibition thinking about the phrase “bodywork of hospitality”. What does it mean to apply the concept of hospitality to the body? Hospitality is associated with hosting, with providing care and refuge. Does the body perform and enact hospitality, outwardly offering care, or is it the site of hospitality, hosting and embodying within itself a place of refuge, becoming a vessel for care? The answer, as proposed by Sylvie Fortin, curator of the exhibition, is not a simple one. Instead, she proposes it is all of the above: both/and as well as both/if, exploring past, present, and future possibilities of the body as host. Through the vastly diverse and barrier-pushing artwork included in the show I don’t know you like that: The Bodywork of Hospitality, the hospitable body extends and stretches in shape, transforms its functions, and reimagines its very way of being and engaging with the world. Not for the faint of heart, the artworks pull apart and put back together sensations of the body, miraculously pushing us into an unknown future while maintaining our solid human sentiment.

The viewer is almost immediately greeted with a crossroads, as the exhibition space is largely divided into two main spaces (or so it seems). To the right, the gallery holds works that reference the past. Before moving into the unknown, I’m transported back in time: dark parts of history where bodies have been experimented on and exploited are explored and revealed in works like Rodney McMillian’s mixed media piece Between the sun and the moon (For H.A. Washington), 2020. In this piece, a timeline is laid paper on in inky washes of acrylic and latex, revealing a horrific history of purposeful medical malpractice on people of color. Statistics like, “1990s: Norplant, a long-term contraceptive, was implanted into young black girls at alarming rates in Baltimore Public High Schools” demonstrate this long-standing history of testing medicine on communities of color without their consent. Perhaps the most well-known example of this is the story of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cells, which were the first immortalized human cell line, and were responsible for furthering medical research tremendously. However, Ms. Lacks’ cancer cells were taken without her or her family’s knowledge or consent. Crystal Z. Campbell’s piece, Portrait of a Woman, gives form to the life of Ms. Lacks. This portrait shows up as an image of Ms. Lacks on a solid glass cube that could fit in the palm of your hand. Inside the cube: HeLa cells. The cube rests inside a wooden post in the gallery, compelling you to crouch down to see the details of Henrietta’s face — bringing to light a horrifying example of hospitality being abused and exploited.

In Mounir Fatmi’s photo series The Blinding Light, we see a hospital room during what looks like the middle of a medical procedure. Doctors in scrubs stand under a bright light around an operating table. But this modern medical scene is obscured; paintings of saint-like figures (complete with Renaissance-esque gold leaf halos) grab onto the patient’s leg, which has been turned completely black. Fortin explains that the series references the story of the ‘black leg’, which comes from the 10th century, where medical doctors believed they could transplant a human leg from a corpse onto a human that was alive. And although the procedure (obviously) didn’t work, this was one of the first recorded cases of transplantation. This practice, too, did not regard the deceased or their family’s knowledge or consent. This selection of artwork interrogates the body as a site of potential hospitality by revealing bodies that have had ‘hospitality’ thrown upon them, regardless of their cost. Without the consent of bodies such as Henrietta Lacks, the notion of the hospitable body becomes inverted. One cannot have hospitality without consent, as both parties must be in this relationship together. ‘Host’ and ‘guest’ must be in agreement, at equal stakes, allowing both a choice, a choice that is essential within the notion of hospitality.

I am enraptured in the history/horror of what has been done in the name of ‘medical science’ when I catch my breath due to the deep breathing emanating from Ana Torf’s video piece When You Whistle, It Makes Air Come Out. Phrases like “When you breathe, it comes into the mouth” are shown on a single-channel video, reminding you to take note of your breath, your body. The steady rhythm of long breaths ground you. You are present. You exist. You are here in your body. But where does your body end? If you breathe out, is part of my body leaving, dissipating into the air in droplets? Whose body is my body? Is that my breath I am hearing, or is it the sound of the machine? This is the introduction of the body as a tool separate from the self, a site of (consensual) potential and play as the threshold of inside and outside the body, the separation of me and you, is enticingly stretched and abstracted. This malleable body is not quite science fiction—or perhaps the works will reveal the sci-fi-esque experience of existing inside a body as a shell.

In the adjacent gallery, the body as a carrier bag is undone. The vessel is pierced, skin opened, with abjection sure to follow. Whereas the first gallery contained works that explored what has been done to specific bodies—contained within the body—the next gallery blows the body wide open. Here, the body becomes the medium—the raw materials from which hospitality and care can be built. Extending towards you in the gallery is a dark and looming piece: Untitled (Entrails) by Rodney McMillian. Playful and foreboding, chandelier-like black tentacles hang suspended in the center of the space, reaching to your left, right, and straight towards you. The piece resembles something (entrails?) inside the body, something that is not quite inanimate. It is not moving, but it is certainly reaching. It is not intestines, but it is certainly something ‘of the body’. It does not matter if it isn’t alive — your body, your senses, and your imagination makes it so.

A nearby piece has the same effect. Jean-Charles de Quillacq’s installation piece Superclogger is comprised of an aquarium tank filled with clear liquid and a silicone mask inside that resembles a human head, water spewing like a fountain from the mask’s ear. The piece seems more weird and eerie rather than evoking a psychological (or bodily?) reaction, like McMillian’s piece. A decapitated head squirting water? Innocent enough. However, that tank is not at all filled with water. Upon closer inspection, I discovered it is artificial sweat, spewing and splashing just a foot or two away from the wall label, where I learned this disturbing information. I was repulsed by viewing such a vast amount of sweat, and the fact that it is artificial somehow adds another layer of repulsion—and interest. (What exactly is fake sweat made of?). My skin tingled and my mouth became dry as I tried not to feel as if I could taste the sweat. I could not bring my body close enough to inspect it, instead becoming hyper aware of my body, creating a deeper, strangely sensorial way for me to engage with and, in a way, become part of what was happening in the exhibition space. Both/and. Even more unsettling was how I was not disturbed until after I found out this small piece of information. For all I know, this information could be a lie, leaving me to wonder how ‘real’ or ‘unreal’ my reaction is. I could physically feel my reaction—but if it is purely physiological, is it arbitrary? Could I get over this gut-repulsion? As seduced as I was, I had to walk away.

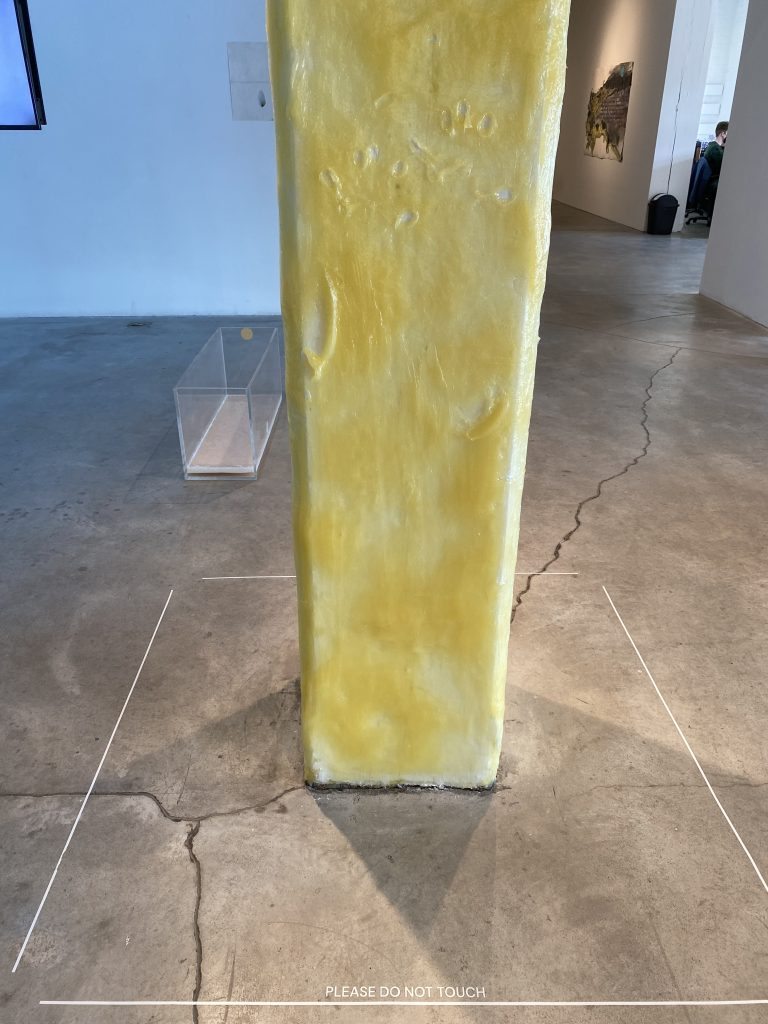

I almost collided into another piece by de Quillacq: Armpit. For this piece, the artist has slathered a column in the gallery entirely with amber-colored petroleum jelly. Strategically placed, other viewers had clearly run into the piece (or perhaps they simply could not restrain themselves from touching it), as a set of hand prints were imprinted in the gel. The closer you get to the piece, the more visceral it becomes. The jelly is slimy, shiny, sticky—you do not need to touch it to imagine its texture. Closer yet, I perceive hair emerging from the jelly. At second glance, you see that thin pieces of hair jut out from all over the jelly. The hair is (you guessed it) armpit hair. To obtain human armpit hair for this piece, Charles de Quillacq met a local man on Tinder, requesting a donation of armpit hair — which the man gave. Here, the body as contained is complicated and collapsed, its fluids spilled, splayed out for us to see. These artists cleverly use materials that are not actually living tissue (hair being dead tissue), and use it to awaken something within the viewer. We remember the smell of sweat, the feel of hair, the sensation of squishing petroleum jelly — yet, these elements of the body (sweat, hair) are not on us. They are not attached to any human body at all invoking the uncanny, something like deja vu. It is us, but not us: a part of our body that is no longer in its place. What is next — decay? Death? The parts are as evocative as the sum, but more eerie and dangerous as they threaten the boundaries of our body that contains us.

In Skin Flick, Adham Faramawy has installed a single-channel video on three monitors atop a mound of dirt and various shaving cream cans. Stacked vertically, the piece can be seen, heard, and smelled almost anywhere in the gallery, making its presence known — one of the main characters, an alien creature, speaks to the viewer, while another smears shaving cream all over their body as the wind blows, bringing to mind Venus in her shell. The piece is otherworldly and textural, both figurative and floral as it explores, encourages, and celebrates the absence of these bodily boundaries, seeing the potential in flouting them despite the constraints that capitalism, gender expectations, and Western cultural standards place and force upon our bodies. What is possible if we are not contained by these presumptions, if we are not restrained even by our physical bodies? Both/If. The artist has installed a single-channel video on three monitors atop a mound of dirt and various shaving cream cans. Stacked vertically, the piece can be seen and heard almost anywhere in the gallery, making its presence known — one of the main characters, an alien creature, speaks to the viewer, while another smears shaving cream all over their body as the wind blows, bringing to mind Venus in her shell. The piece is otherworldly and textural, both figurative and floral.

“The work is about a very porous body that is embroiled in various relationships of desire and toxicity that expands both its internal functions and its external appearance,” Fortin explains. “It’s about taking substances to increase your performance, but also taking beauty products to maintain your youth. The piece pulls from all of these things that are central to Western culture, but teases out a different reading. One where the notion of the human no longer makes sense. There becomes this separation of the human from other life forms in scientific terms, in mythological terms, and in terms of what we consume.”

Perhaps the body no longer makes sense — it is changing, reshaping, becoming more adaptable to survive. If our environment, or our own bodies are no longer hospitable to us, then perhaps we must alter the body to become more hospitable. This concept is explored further in Ingrid Bachmann’s film The Gift, located in an adjacent space. If de Quillacq’s piece Armpit is the skin of the exhibition, then Bachmann’s film is surely the muscle. A standout piece in the exhibit, this film is moving, a stunning collaboration that interweaves contemporary dance with modern medicine and psychology. Two dancers precisely move with, towards, and around each other. Muscles are flexed and strained, moving in tandem and against. The artist directed these dancers to respond to the act, exchange, and experience of organ transplantation, one dancer representing the donor and one representing the receiver. The artist informed me of the extensive research this project demanded, including numerous discussions with both organ donors and recipients — a detail that is felt in the honesty and care pouring forth from The Gift. In the film, behind the dancers, darkness, the unknown. Is this unknown territory how much we truly don’t know about organ transplantation, or is it the other side of our life? Life and death, give and receive. To give hospitality by way of donation, and to offer a place of hospitality inside your own body, a home for the organ itself. Here, the ghost seeps out of its shell to stretch what is possible within and outside of our own bodies—the ultimate gift being part of ourselves.

Transplantation and transportation considered, Fortin moves our bodies through the exhibition by way of altering our body’s potential state, allowing us to pause and consider that our body is not so static, but instead a location and tool to care and to host.

Outside both sections of the exhibition lies an entirely different space, mostly used for events and performances. In this space, I am confronted with a lone installation of bright and soft pinks and blues in the middle of a spread of concrete. The installation, by artist Bridgette Moser, is located farther away from the other sections of the exhibit, and rightfully so, as it is somewhat of a departure. A space for the surreal and uncanny, the installation invites playfulness and (lots of) humor: Crocs have legs, chairs have hands, and inflatables have pecs and a six pack. Even the artist’s body itself, which appears on a screen in the middle of the installation, becomes a plastic plaything. The artist claws at her intestines in the film (the organ actually being a child’s toy) along with other disturbing yet clever shenanigans. In her performance When I’m Through With You There Won’t Be Anything Left, Moser activates the installation by wreaking delightful havoc: her performance is unbelievably thrilling, convincing, and downright hilarious. Using a variety of strangely anthropomorphic props and soundbites taken from pop-culture, Moser disembodies everything and twists things just slightly off. Here, she prods, pokes fun at, and interrogates body image and expectations as well as our current culture of beauty and health. Interestingly, Moser has experience working for a plastic surgeon, allowing her to perceive the human body in strange and unexpected ways. Although this piece has a mood that is at a contrast to most other parts of the exhibition, it, too, considers the body as raw material and as a site for potential. Here, hospitality turned inward, pointing a mirror to our own bodies. How we care for our own bodies inevitably affects how other bodies are cared for. Our own body as host is all of our bodies as host.

Throughout the exhibition, the hospitable body can be seen used unethically under the guise of ‘progress,’ used as a tool, as a type of building block that can be opened and transformed for potential and survival, and used as a mirror, satirically showing us what a ‘healthy’ body is not, what a hospitable body has the potential of becoming if not continuously interrogated again and again. Exploring these different avenues of hospitality, these artists rework the body, compelling a type of care that is desperately needed for us to push forward, for the body to survive.

I don’t know you like that: The Bodywork of Hospitality was curated by Sylvie Fortin and was on view at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts from December 9, 2021 through March 20, 2022. Read the interview with Sylvie Fortin to learn more about the curator and her larger curatorial practice.

Christina Nafziger is an art critic, editor, and writer based in Chicago (occupied land of Ohklahomo, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Odawa people). Earning an M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her research focuses on the effect photo collections and archiving have on memory and identity and the potential capacity these collections have in altering and editing future histories. Working with a collaborative approach to her editorial work, her writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices and how they engage with archives.