Featured Image: Jyreika Guest (left) performing in a music video for the livestreamed theater production grelley. Guest stands on a crate and gestures toward the video camera, surrounded by lighting equipment and a basic set design. At right are crew members (L-R) Eon Mora, Kevin Veselka, and Glamhag. In the background another actor checks their outfit in a mirror. Filmed in Chicago, May 2021. Photo by Sarah Elizabeth Larson.

This is the first in a series of articles made in collaboration with the Chicago Arts Census to explore the living, labor, and material realities of art workers in the city of Chicago. To learn more about the Census, how to get involved, or how to take the survey, please visit: https://chicagoartscensus.com/.

Click here to read the second article of this series.

To get to the Internal Call Center you have to enter the museum’s loading dock, head down endless hallways of windowed offices—the home of Curatorial, Education, the Director, the President (a.k.a. the people who neither know nor want to know you exist)—hop down two or three flights of stairs, and weave through the maze of Membership offices to reach an enclosed alcove of four ’90s-era PCs precariously balanced on top of cardboard scraps gathered from forgotten subterranean piles. With days that begin in early mornings and end in late evenings, the cardboard is an ill-thought-out attempt to ward off carpal tunnel under the glare of a shaky fluorescent sun. Your time in the basement, however, has an expiration date. Any day now your job will be outsourced to the company that the museum plans to hire for all Membership solicitations, calls, complaints, and questions. For around minimum wage, your shifts are spent letting people scream at you on the phone (or in person on your lucky above-ground days) and creating a training manual to be read by someone someday soon in another underground office filled with more convertible furniture than people.

Around 90 percent of your co-workers identify as women; the majority are white women. The few women of color in the office are routinely chastised by managers and directors for their “volume” and “tone” while on the phone. You do not qualify for health insurance. During storms, your small bunker can flood; it’s your responsibility to avoid the slowly seeping groundwater and live computer wires. When you tell people where you work, they answer with variations on a theme: “are you an artist?”, “you’re so lucky to work at such a beautiful place”, “it must be amazing to work around so much art!” You never know how to answer. You write sometimes, but mostly you just want to be able to pay your rent. However, your basement is neither your grocery store nor your coat-check stand—you didn’t have health insurance at those jobs either, but hey, at least now you have your own chair? Addendum, other people use your chair. It is not technically your chair; this is just something you tell yourself to stave off panic’s Everclear bite.

My time spent working in and around arts organizations while writing, or not writing, has been a long lesson in invisibility. Who is seen, whose labor is seen or unseen, who matters and who doesn’t matter under the eyes of power? Though my story is relatively tame and couched in privilege, these facts do not lessen nor negate the truth: the art world is not immune to the harms that accompany the use and abuse of power. Rather, the art world is beholden to and forged within the machinations of global capitalism. At their worst, all art and cultural organizations (museums, galleries, theaters, performance venues, the music industry, and on and on) can simply reflect shards of a burning world, echoes of white supremacist surveillance, mirrors of broken memory, and silenced voices. Yet art and the communities it grows can also hold their own promises. There are moments of liberation, witness, participation, life, and desire. That moment where your breath leaves you like the ghost of a thumb in soft fruit, thunder in the pineal gland, unexpected moth wing grace.

There’s a stickiness then, a slipperiness or a friction inherent to the idea of “art worker” as an occupation and identity. Who is, and who gets to be, an art worker? What is the use of art worker as a descriptor, a claim; it’s histories and genealogies? How does such an identity function for life and art bound by rising precarity? What do art workers need? How can we make and find collective resources for art workers? Where does our unspoken and dismissed labor live?

Such questions do not just carry ethical weight but hold material consequences, as the arts are an economic powerhouse within the United States. In 2013, the arts sector included 2.21 million artists in the U.S. workforce, 95,000 nonprofit arts organizations and 656,000 additional arts businesses, 766,000 self-employed artists, and $151 billion in consumer spending. In 2018, the Chicago-Naperville-Arlington Heights, IL area was also cited as one of the top 20 Arts-Vibrant Large Communities (Metropolitan Areas or Metro Divisions with population over 1,000,000) and the Chicago Metro Division ranked in the top 7% of communities on overall Arts Providers and in the top 2% on overall Arts Dollars.

During the summer of 2020, the minimum wage in the city of Chicago was $14 an hour for employers with twenty-one or more workers and $13.50 for those with four to twenty workers. For folx in the service industry who receive tips, minimum wage was $8.40 and $8.10, per that same criterion. As of June 2021, average rent in the city of Chicago was $2,012. Near the beginning of the year, the Art Institute of Chicago furloughed 109 employees while the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago laid off 17 out of 162 full-time employees and 24 out of 49 part-time employees. As arts organizations and the city’s service industry shuttered their doors and folx were left with fear and uncertainty for the future, state sanctioned violence and vampiric environmental racism continued.

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the urgent need for the creation of—and equitable access to—sustainable Chicago-based community resources for art workers. Art workers who are performing artists or who work within the performing arts (in theaters, music venues, concert halls, dance studios) have been uniquely impacted by the pandemic as their practices have been rendered nearly impossible by city and state health guidelines. While this impact has been recognized through federal and state aid, such aid isn’t easily accessible for all performing artists and art workers.

In a recent Chicago Reader article, Olivia Junnell, the development and outreach director for Experimental Sound Studio, detailed her experiences on various boards for grants and aid for the performing arts, and illuminated how the very structure of the grant application process immediately excludes great swathes of art workers who may not have reliable internet access, neurodivergent applicants, or those who do not have the privilege to become familiar with grant writing practices. Such structural disparities even extend to relief programs that position themselves as both cognizant of and in conversation with the historical inequities that the pandemic has illuminated. For instance, Chicago’s Performing Arts Venue Relief program explicitly states that its funding was (and potential future funding recipients will be) chosen through “an equity lens that considers the history of disinvestment and the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 on the South and West sides of Chicago”. Yet to qualify for funding through the relief program, organizations are required to meet criteria such as a PPA (Public Place of Amusement) or Music and Dance license in good standing, a non-P.O. Box street address, proof of ownership or year-round lease of a venue or club where performing arts are the primary amusement/activity (as verified by past programmatic listings and website content), proof of operation since at least December 2019, proof of at least 25% revenue loss due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and must not owe more than $2,500 in unpaid fees or services to the city of Chicago.

Though the city asserts that the criteria are implemented with intent to alleviate harm, these requirements can also enable the same barriers to access. The re-circulation of these inequalities not only defines a system built upon intersecting disenfranchisements but also gives insight to a fundamental confusion regarding the performing arts. Under the shadow of COVID-19, what does the future hold for the performing arts and what does this mean for performing artists and art workers?

MoMA Magazine’s artist-run project “Performing at a Distance” features pieces by performing artists on how the pandemic has impacted their practices: their time, their audiences, their bodies in public space, now private. Their writings touch on the knottiness of time, the centrality of physical presence, and the shift from the immediacy of the body to the mediated moments of the screen. To join and to watch doesn’t feel the same. What now makes a performance? Where do musicians, dancers, actors, dramaturges, stage technicians, choreographers, conductors, composers, all performing artists and art workers go from here? There are hosts of think pieces on this very topic, reports on the potential trials of safely reopening performance spaces, and conversations with leaders in the performing arts. Stability has long been not guaranteed, yet a common thread throughout each of these conversations is that art has a future, and the performing arts have a future; there will be a next note, a next step, a new breath.

However, art workers who identify as members of BIPOC communities occupy increasingly precarious and vulnerable spaces. A 2020 report by Enrich Chicago, an arts non-profit centered on resources for African, Latinx, Asian, Arab, and Indigenous artists and organizations, found that more than 70 percent of boards and “decision-making staff” at foundations and arts and culture organizations identify as white and that organizations with strong BIPOC leaderships “receive 50 cents for every dollar that white organizations receive.” Structural inequality does not just touch and shape our histories. It does not exist within an elite monied stratosphere. There is no clear source, no one solution, no beating heart within this labyrinth. Rather, inequality is so enmeshed within our lives that it is taken in with every breath, step, and moment of the day. Inequality in the arts matters. In the words of Enrich Chicago’s director, Nina Sanchez, “arts organizations are not just arts organizations, they’re often health service organizations that have arts programming. They are community organizing spaces… Art is approached in a cultural way […] embedded holistically, in everything.” Coupled with COVID’s disproportionate impact on majority BIPOC communities it is now more important than ever to understand how the relationship between structural racism and classism brought us to the current moment. Only with such understanding can we rebuild for a better future.

Thus this piece centers inclusivity, diversity, and intersectionality at the heart of its explorations. We must be compelled by a holistic understanding of how art workers are both formed through and continuously shaped by the large-scale forces that dictate our survival. Classism and racism are not things that happen beyond us, or just to us. Those burdens, those trappings, are carried within communities—carried in you, carried in me. Any understanding of work and organizing within the arts must be powered by a commitment to collective wellbeing. What does organizing and action accomplish if people remain vulnerable, forgotten, left behind? This work is for everyone.

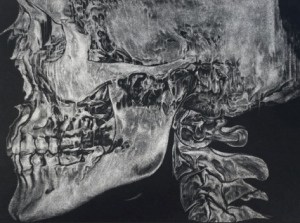

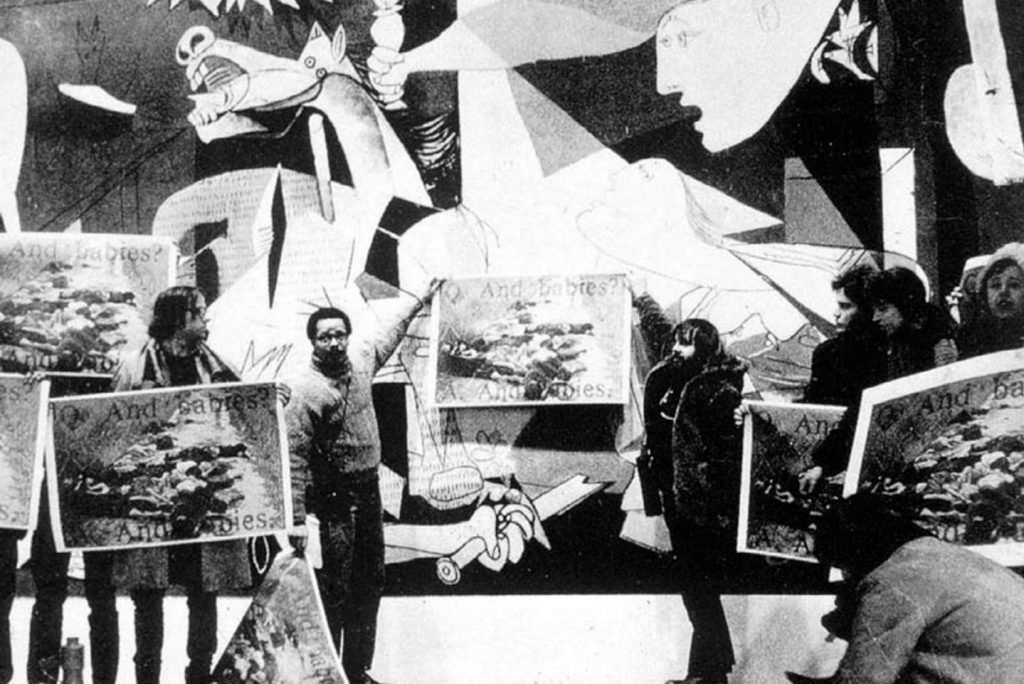

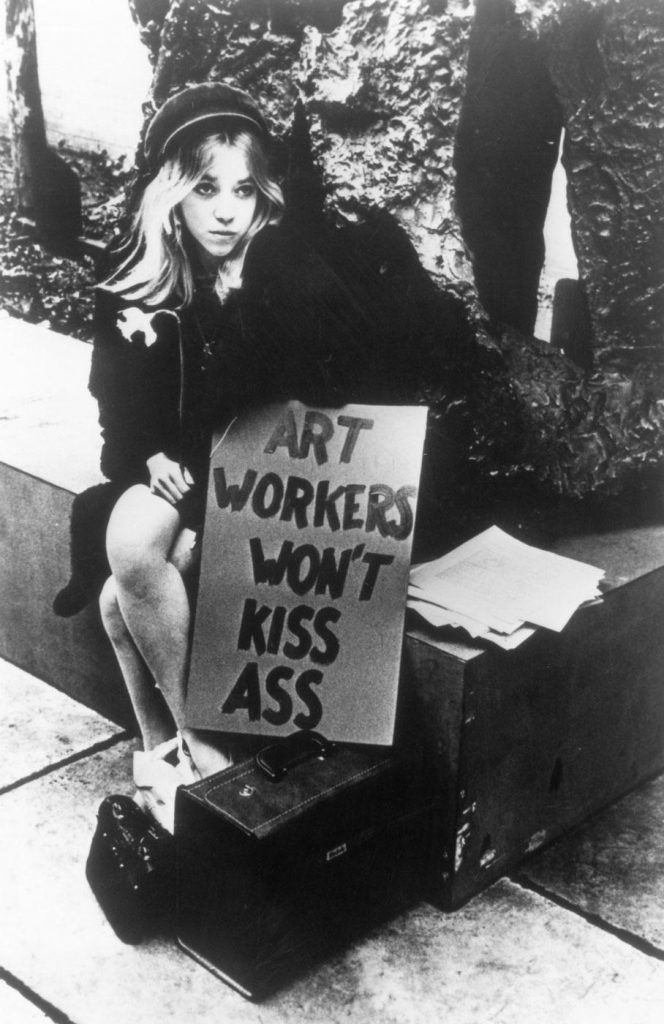

During the late 1960s, the Art Workers’ Coalition was formed in New York City as a response to unscrupulous and discriminatory institutional exhibition practices by MoMA and other local art museums. The AWC planned systems that encouraged institutional accountability for artistic labor, equitable arts funding models, and much needed studies on the relationship between the arts and corporate sector. When I say the corporate sector, think of the origins of museum trustees, directors, and investors. Think of where the money flows and how those dollars trickle down to impact every facet of community access and, in turn, collective quality of life. Think of the Sackler dynasty’s long shadow over institutions like the Tate museums, the Louvre, the Guggenheim. Think of Nina Sanchez’s words, the arts are “embedded within everything.” Though the AWC was originally created as a local group to strengthen artist agency and bargaining power when in dialogue with larger arts organizations and institutions, the Coalition’s membership and concerns soon grew. Over the 1970s, the AWC expanded to include artists, arts administrators, journalists, teachers, and gallery and museum workers. Together Coalition members would work on identifying inexpensive exhibition spaces, sustainable employment, and affordable housing opportunities. Inspired by America’s New Left, the Coalition fought for equal access to services and resources aimed towards supporting working creatives. The figure of the artist was then in essence reconfigured under the AWC’s political framework. Instead of an individual creator, the artist was now a member of a broader community beholden to the same material forces and invested in a collective good.

Where can we find such creative community? How does one balance the needs of the individual with working towards a common goal? Who do you work for, where do you belong?

There’s a reason why Theaster Gates’ Rebuild Foundation quietly failed in Saint Louis; it is not the community to which Gates speaks and in which he claims membership. That would be Chicago’s own South Side. At the corner of 43rd Street and Langley Avenue there once stood the mural, The Wall of Respect. Envisioned by the Visual Arts Workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture, Respect was a space for artists, makers, thinkers, and activists to converge and create a monument to and for Black Pride and Black communities on the South Side. Several artists involved with the mural would go on to play a role in the founding of AfriCOBRA, a pan-African arts movement dedicated to exploration and celebration of the visual languages that informed Black life and pride in diaspora. Connected to the broader Black Arts movements of the time, AfriCOBRA centered the collective as a tool for political change and empowerment.

In 2019, curator and art historian Dr. Jeffreen Hayes organized the exhibition Nation Time, a collateral event in that year’s Venice Biennale. Hayes explored how AfriCOBRA’s visuality worked between the past, present, and future; how the movement presented temporality on a continuum, with community and possibility positioned at its forefront. Hayes continues, in response to AfriCOBRA’s investment in a Black futurity, “we must ask ourselves how the past reflects today and what we can learn from these connections for the future. AfriCOBRA is thinking of the past and in the present moment there is much we can learn from the collective… to craft a future abundant with possibilities.” In an interview with Sugarcane Magazine Hayes also asserts the material demands of such action, “we tend to forget that these artists are also human beings who have lives, families, and experiences just like the rest of us. They must sustain themselves.”

The American Occupy movement of the early aughts was a response to the mushrooming of the neoliberal state, its increasingly deregulated financial institutions, rampant wealth inequality, and the growth of precarious and or otherwise contingent labor. Infamous for the Occupy Wall Street protest, the movement was a seemingly democratic effort to combat the collective injuries sustained by the existence of the one percent. The movement’s arts and labor theory for the most part centers an idea of disenfranchisement in a way that draws upon the language of performance, a system that blurs the boundaries between life and art. Capitalism’s emphasis on flexibility has led to a regime of labor where individuality is consumed by new paradigms of work. Flexibility, now, is coded within precarity—that corporate doublespeak where your “creativity”, “adaption”, and “invention” are said to be rewarded. There is no longer the option to turn off or clock out. Stability is, for most, a thing of the recent past. The figure of the artist, the creative, has been co-opted and rebranded by the gig economy: everyone performs to survive.

Artist and theorist Hito Steyerl likens the neoliberal necessity of performance to “economies of presence,” and presence as the potential for “unmediated communication, the glow of uninhibited existence, a seemingly unalienated experience and authentic encounter between humans.” The possibility of such bodily epiphany, a match struck behind the eyes, is both a false promise under the shadow of the gig economy, and a slippery slope for musicians, dancers, performers, and other art workers whose bodies are under siege. Late capitalism’s unchained melody. Thus when Paolo Virno asserts a political potential within the realm of “virtuosity,” a lived experience that “happens to the artist or performer who, after performing, does not leave a work of art behind”, one must ask who has access to this potential? Where does it live?

The Occupy movement is ultimately thought of as a failure. Why? Let’s think first on the idea of performance. Performance depends on the performer: performance can be necessity, privilege, or survival. For performers who identify as BIPOC or LGBTQIA+, performance—code-switching, the notion of existence—in a world filled with hate is a matter of life and death. Who then is the performer, the artist, in Occupy discourse? Who has the privilege to discover their artistic practice as a site of political praxis, who does not need to depend on or otherwise locate themselves within an ambivalent collective? They are white, they are male, they are the perfect consumer, a symmetrical site of production and reproduction; a capitalist subject ripe for picking, both in danger of and aching for controlled demolition. If the Occupy performer was anything other than the figure of the lone genius, Friederich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, couldn’t there have been systemic change? Couldn’t Sam Greenlee’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door have come to pass?

What then are we here for: work, art, fulfillment, life? The projection doubles up and the film reflects upon the wall, the image splits slightly askew, our lines weave together. What did you come to see? It is all a patchwork, stitched with spidery glass on the supermarket magazine rack. You can’t talk about one without touching the others.

The day you leave the museum with a new job you cry in relief. You move to an art school. Tuition remission is available for employees. You register for an evening class with a faculty member whose course description begins with the Detroit auto industry and ends with MTV’s The Real World. Their writing excites you; it opens possibilities that you could never imagine. First class, you get to your room and an old panic hits, the kind where you’re struck wordless and afraid. You are not smart enough to be here, you should not be here. You clean and make schedules, you don’t write. This was a mistake. When your professor arrives, you notice in aesthetic admiration their dark rose toenail polish and what you now remember as a small tattoo of an Anarchist “A” on the crook of their hand. You brace yourself to be asked to leave for countless imagined transgressions.

The first class ends. You’re drenched in sweat, but you begin thinking again. It’s been a while. You don’t pretend to understand or know what happens in class, but everything starts to appear a bit sharper, with clarity. The semester is almost over when the professor says something that etches into your brain: unions.

In academia, multiple communities need, and could benefit from, collective bargaining: graduate student workers, staff, and non-tenured faculty who are all working with little job security or benefits. In a 2018 study headed by the Chronicle for Higher Education, 97 percent of the collective bargaining agreements the study examined lead to an increase in job security for contingent faculty. On the Verge of Burnout: COVID-19’s impact on faculty wellbeing and career plans, a late 2020 nationwide survey by the Chronicle of over a thousand faculty members at colleges and universities, found that more than one-third of respondents considered changing careers and leaving higher education this past year. These changes correlated with the increased stress and untenable labor environments both brought about and amplified by COVID-19. The study also found that BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, disabled, and female faculty were disproportionately impacted by these changes, and many who identify as members of these groups reported their workloads and work/life balances to be unsustainable.

Aspects of modern academia also mirror the precarity faced by many art workers, as both sectors are changing to meet evolving neoliberal paradigms. Andrew Ross’ essay “The New Geography of Work” cites ethnographic evidence gathered by multiple authors in the aughts that states “job gratification, for creatives, still comes at a heavy sacrificial cost—longer hours in pursuit of the satisfying finish, price discounts in return for aesthetic recognition, self-exploitation in response to the gift of autonomy, and dispensability in exchange for flexibility.”

Now back to the classroom.

Windows jut out to grey alleys, the rolling chairs, and tables you rearranged earlier in the morning. Class starts, conversation begins. The question of the hour: why don’t part-time faculty, staff, and graduate students join and expand the faculty union? You can’t stop thinking about it: why don’t we?

You wish you could tell a story of victory, of community, of coming together. But you can’t; you were afraid. Again. Afraid of being fired, losing health insurance, not being able to pay rent, screwing up, getting screwed, again and again and again. The fear is what you regret the most, but as time goes on you feel it less and less. Your voice is a bit louder, solid. If you could tell your professor one thing today it would be to thank them for cracking open the door.

What does action then look like for an evolving community of art workers? This piece, in essence, is a call to provide space for failure, missteps, experimentation, and trust. Art workers, everyone who plays a role in bringing art to the public, can come together to build new structures that work and feel right for all. Yet what does feel right?

Art workers must ask other art workers what they need. Include everyone who has a hand in the labor of art—from the visual, to performance, the literary, and musical arts; the sanitation, administrative, and all service workers at arts organizations. To artists hustling to survive, artists in the service industry, artists who are caregivers who cannot pursue their practice, those with multiple jobs and those whose practices are interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, post-disciplinary. The workers who cannot work, those who have lost loved ones to COVID-19 or any of the myriad unfair and unjust reasons why a loved one can be taken too soon.

I believe in the power and potential of community organizing. When communities come together with a common goal, we have the power to expand access to material rights and opportunities, provide for a diversity of activist voices, and better the living conditions of all workers. Through the work of movements like Fight For $15, the city of Chicago’s minimum wage for workers with large employers (21 or more workers) was raised to $15 an hour on July 1st. Such victory was only accomplished because of Fight’s commitment to ethnic and racial intersectionality and cross-class solidarity. Chicago’s own performing arts communities have a strong history of organizing for the rights of working artists. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s seven week strike in 2019 resulted in the ratification of contracts that promoted equitable pay for orchestra musicians, and the Chicago Federation of Musicians continues to raise and provide direct aid to support musicians impacted by COVID-19. These are critical strategies from histories of activism, parlayed into material plans for more equitable futures.

We must also look to histories of activism and work to learn from the past to build a different future. In her 2021 account of the ACT UP coalition, Let The Record Show, Sarah Schulman asserts ACT UP’s activism succeeded because of the group’s radical democracy. Direct actions that in any way addressed the AIDS crisis did not require a broad organizational consensus. This shared stance meant that the collective’s reach was wider, further, and deeper than any linear plan.

Now ask: what material changes can improve the lives of all art workers?

In Brontez Purnell’s review of Danez Smith’s poetry collection Homie, Purnell writes, “As a writer, I have always rejected the very old and very dead notion that for writing to be ‘good’ or ‘successful,’ it must have a clear thesis, a supporting argument, and an ending. That’s what some of us refer to, in Black vernacular, as cracker bullshit.”

Purnell’s message doesn’t just stand for one’s words; it is a reminder that action, work, and care are not a linear process. On this the future depends.

Annette LePique is an arts educator and writer. Her research interests include cinema, race, illness, and the body. She has written for Spectator Film Journal, Fashion x Film, Cleo Film Journal, Another Gaze Feminist Film Journal, and Dilettante Army. She is an active performance artist with a background in dance and music.