Even 125 years later, we can’t stop thinking about the World’s Columbian Exposition, an extravaganza so large and dense that we continue to unpack its flaws and glorify its vastness. In 1893, Chicago introduced the world to collections of dancers, photographs, paintings, magazines, and yes, even a map made entirely of pickles. The fair influenced how we view and how we curate exhibitions today. It was a spectacle and its history is a labyrinth of stories and mystery, and even a bit of horror.

The Newberry Library is looking at the visual aspects of the fair—exhibiting an extensive collection of ephemera and art—in Pictures From the Exposition: Visualizing the 1893 World’s Fair. The exhibition displays the way artwork influenced people from afar to visit Chicago, as well as those who were living the experience, and how these images served as a means of advertising as well as fine art.

What’s always been so undeniably interesting to me as a Hyde Parker, living on the edges of where the famous fair was once held, is how the naked eye cannot see what once was. The buildings at the World’s Fair dissolved and vanished after just six months. Living amongst the history of the festival is non-existent. We know it, we understand it, but we don’t physically see it. The ghosts that remain are the The Palace of Fine Arts which is now the Museum of Science and Industry as well as a permanent statue on E. Hayes Drive which can’t be missed from Lake Shore Drive. But the real remains lie in the souvenirs that were salvaged and are available to view on exhibition at the library.

According to Newberry’s Director of Exhibitions, Diane Dillon, “City boosters sought to position Chicago on the global stage as a cultured metropolis that had rebounded from the Great Fire of 1871.” Not only were the artworks and performances surrounding the fair notable, but the architecture and state exhibitions were among the draw for spectators.

Pictures from the Exposition highlights the experience of the visitor’s first hand by displaying ephemera advertising the fair and promoting the so-called “utopian landscape,” of the city with big shoulders. Of course we know the fair was far from utopia, as was Chicago. Much is withheld from the history of the fair, as racism and sexism were rampant for the time and for the exhibitions on view across the neighborhood. Segregation and racial hierarchies plagued the fair’s events even though the exposition was meant to exemplify progress. Minorities were subjected to being performers, low-level jobs, and racist stereotypes. Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn, and Ferdinand Lee Barnett published a pamphlet called, The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition, which was passed out to visitors. The pamphlet is featured in a glass box in the library along with the history of the Midway Plaisance, where spectators went to “escape” the high-brow environment of the remainder of the fair. The plaisance was riddled with racist reenactments and “ethnographic-themed villages” that featured cultures from around the world. Frederick Douglass wrote that “the Dahomians are…here to exhibit the Negro as a repulsive savage.”

The Native Americans were propped up as theatrical entertainment as they played the role as “themselves” in their so-called natural environment. On their stolen land, Potawatomi leader Simon Pokagon wrote, “I declare you, the pale faced race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in Chicago city, the wonder of the world.”

Despite this unforgivable controversy, America still largely focuses on the success of the fair, the numbers that were drawn to the city, and the innovation it created. The White City, called so because of the illuminating lights and white stucco buildings, saw 27.5 million people pass through the South Side of Chicago. The neighborhoods of Woodlawn and Hyde Park boomed after the fair, where venues and rail systems sprung up in order to engage their audience.

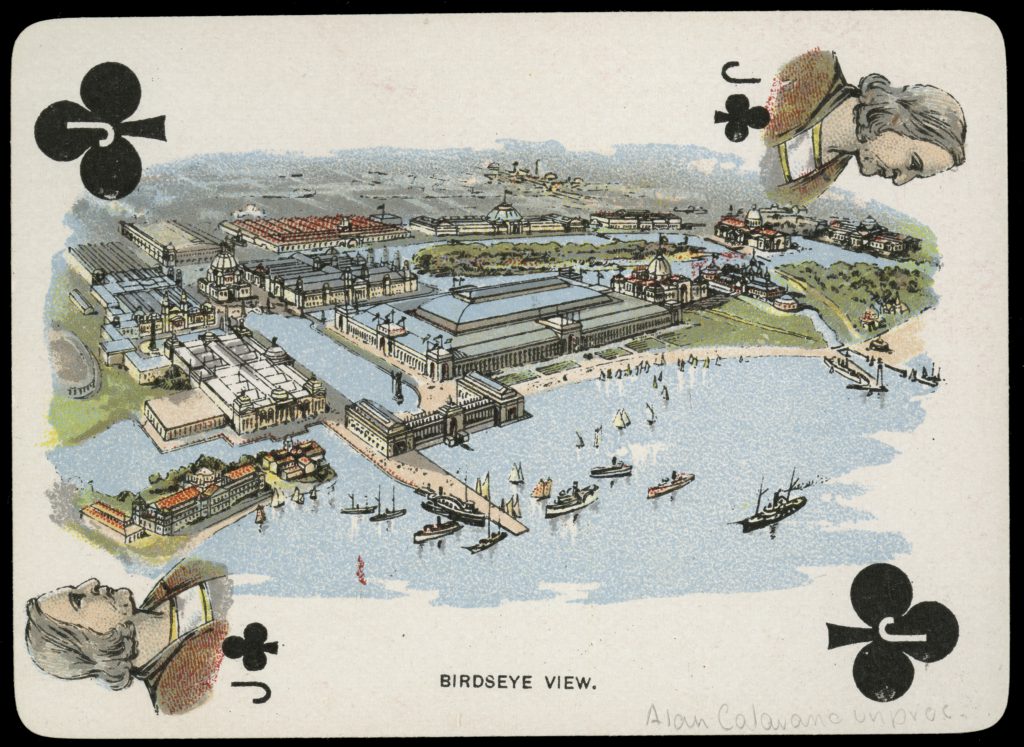

The ephemera in The Newberry’s exhibition includes souvenirs, postcards, hand-held fans, and larger paintings all displayed along tables and on the gallery’s walls. The exhibition opens with a large sculptural Ferris wheel that doubles as a postcard holder, both became increasingly popular after the fair. Walking into the gallery includes more delicate items. Paper envelopes especially capture my eye as they are printed with orange, purple, and green ink and feature barely visible scenes from the fair. Playing cards and postcards are other interesting artifacts which exemplify the span of advertising involved. Other objects include John W. Green’s chromolithograph fans which beautifully detailed the islands and waterways surrounding the fair.

Most of the photography of the fair is architectural photography. According to the library, the fair charged, “$2.00 to bring hand-held cameras on to the grounds.” A map cane is even featured as a souvenir created by the Columbian Novelty Company. The library explains that the items like the fans and canes probably weren’t used but were purchased as mementos. Moreover, people who could not attend the fair even purchased these items as they wanted to experience the excitement from afar. As for larger pieces of work, the grounds and all of the buildings were filled with large-scale artworks. The “Statue of Republic” chromolithograph by Francis D. Millet appears like a watercolor piece utilizing pastels and vague background imagery.

Spanning 600 acres, the spectators were able to live amongst new inventions like elevators and even the first electric chair. The zipper, Cracker Jacks, and the first voice recording were all exhibited at the fair. Moreover, on the Midway Plaisance stood the first Ferris wheel. Chicago, a city of summer festivals, had its first start with the 1893 fair. The history of city planning and consumerism ties into the Newberry’s $12.7 million nine-month renovation of the gallery. The library itself opened in 1887 and with its new look, hopes to appear more appealing to non-scholarly visitors—as the library is free and open to the public (and somewhere I never visited until writing this article).

A friend of mine has a 1893 World’s Fair glass etched and inscribed with a date and the name of the fair, it’s definitely a family heirloom. They have it propped up in a shelf in their apartment—a prized possession passed down from a great-great-great someone. I have a replica of a map of the fair in my kitchen. It hangs above the microwave with thumb tacks pinned in the corners. It’s a signifier of my roommate and I being proud Hyde Parkers through and through. Souvenirs, though real or fake (like my map), were collected individually and kept as relics of identity, nostalgia, the past, and probably a lot of Chicago pride.

The Newberry Library is open Tuesday through Thursday from 9am-5pm and Saturday from 9am-1pm. Pictures From the Exposition is on view until December 31st.

FEATURED IMAGE: The image features outside of the entrance to the gallery. A large Ferris Wheel is displayed in a glass box that doubles as a postcard holder in the right side of the frame. In the middle is the door into the gallery with text on the wall. Courtesy of The Newberry Library.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, Broadly, Rewire, i-D and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, Broadly, Rewire, i-D and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.

Photo by Jordan Levitt.