I’ll begin at the end. Arms raised, knees levering, booties popping, we danced to the beats served by DJ Hijo Pródigo in the Currency Exchange Café, which had turned into a bar for the night, serving up cocktails loaded with activated charcoal. We had an hour before been perched next door on stools and benches for a reading at the BING art books store, and an hour before that stood chatting with cheese cubes on napkins in the Arts Incubator gallery. Nearly a festival in itself, it was the closing night of the monumental ECLIPSING festival: three months that included a performance series, a group and a solo exhibition, workshops, a vegan market, and a “performative lecture” in four arts venues around Chicago.

The festival, whose full title is ECLIPSING: the politics of night, the politics of light, was organized by Amina Ross and took place between January and March. The word Ross used to describe the robust programming is “holistic.”

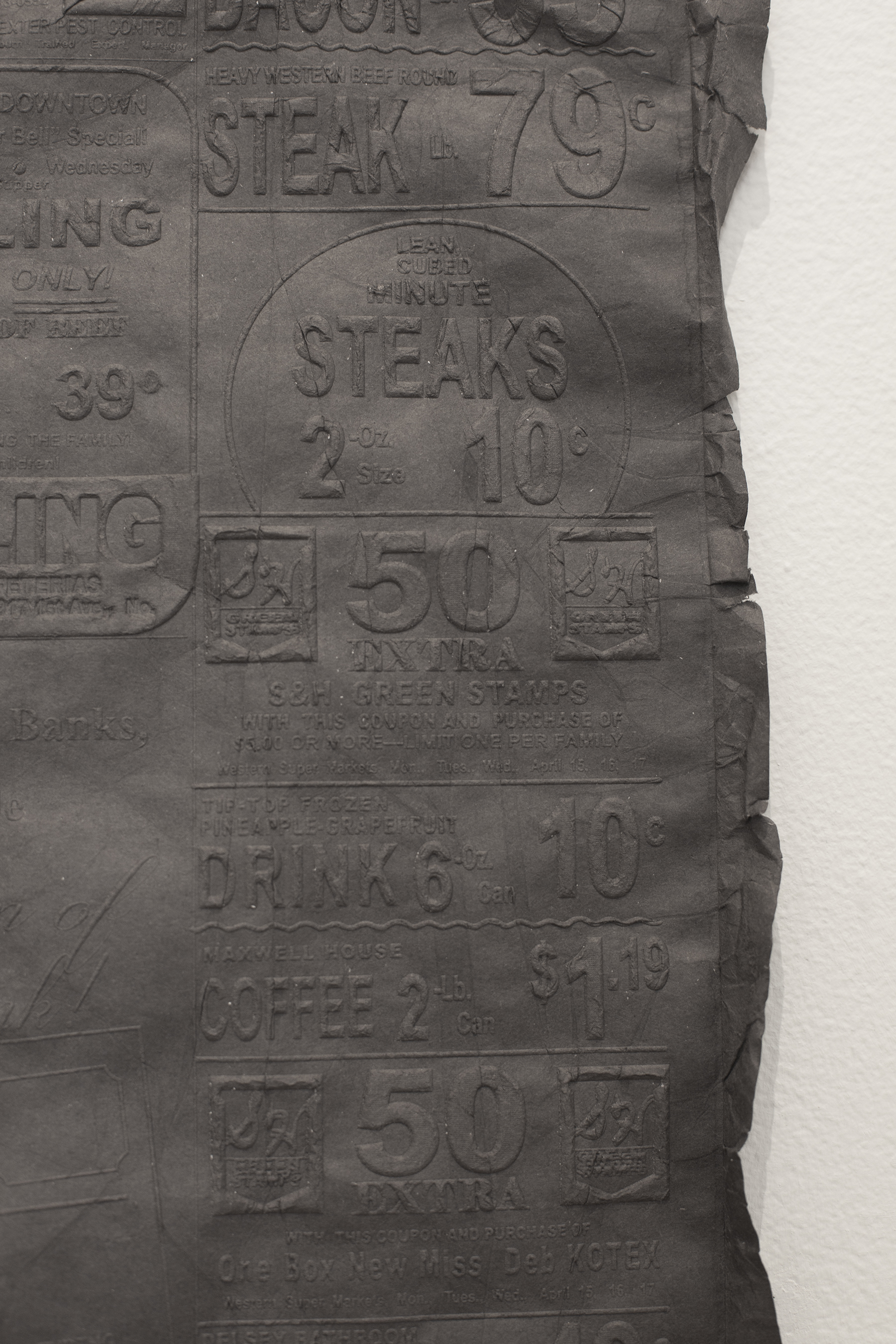

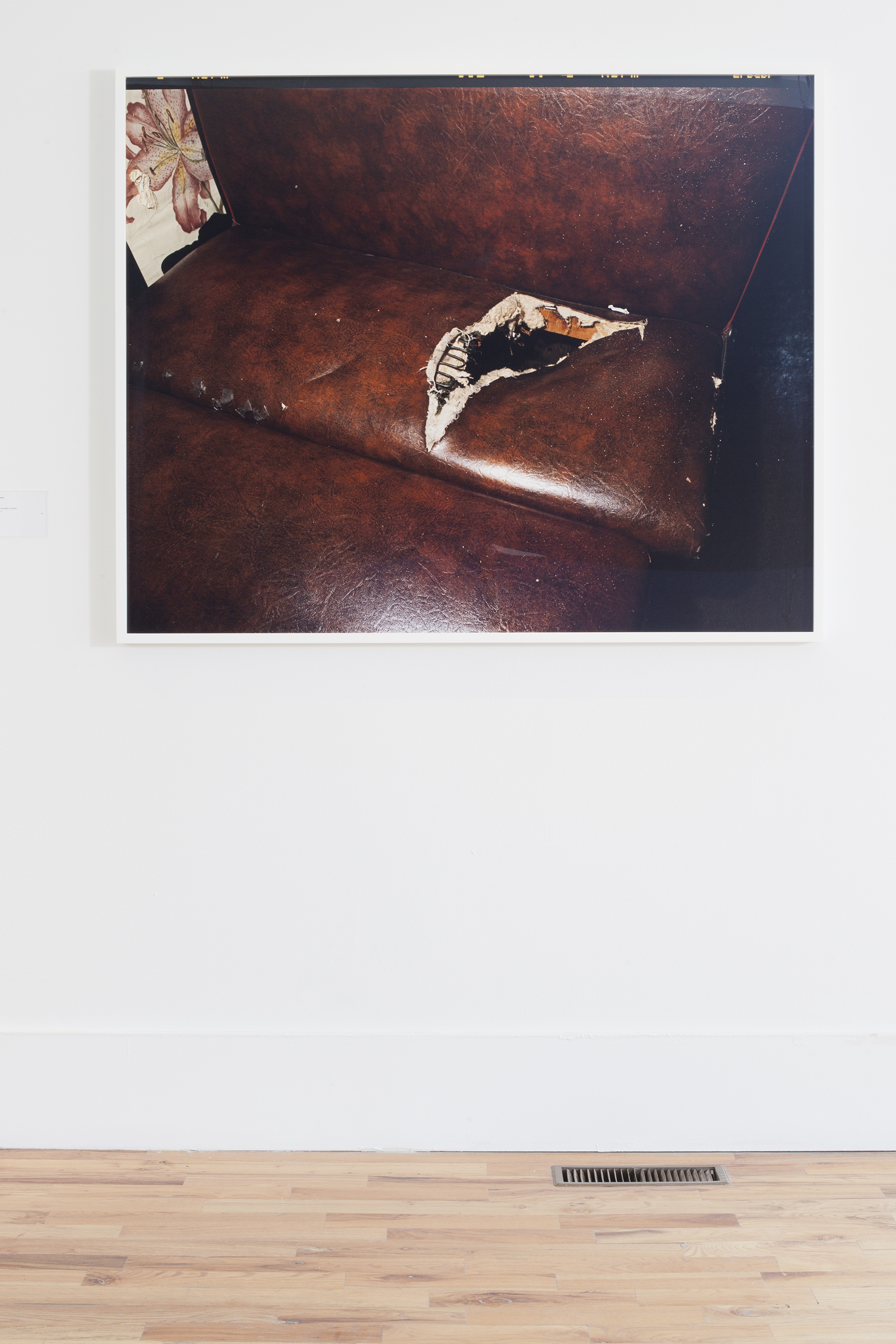

An eclipse is a drama, a shifting in the relationships between the looker, the looked-at, and the body that uncouples them. The individual artworks and performances, as well as the curation, were therefore attentive to their relationship to us, the lookers. In the group exhibition (co-curated by Justin Chance), The Birmingham News, 1963 by Bethany Collins and patRIOT by Angela Davis Fegan both presented black text on black paper, making one work (squint, move closer) to decipher their meaning. Deana Lawson’s Portal beckons the imagination into a world within a hole torn into a brown leather couch. Pass behind the black curtain in the far corner of the gallery to investigate the sound of a voice, and find a (projected) mouth speaking out of a mound of soil in Shala Miller’s Untitled (The Seed Sings a Secret Song) — another portal.

On March 7th at Threewalls gallery, Ross sat cross-legged on the floor, next to artists and healers J’Sun Howard, Khadija Kysia, A.J McClenon, and Jared Brown, who sat on a couch bracketed by floor lamps. In a cross between a panel discussion and your best friend’s living room, the “performative lecture” centered on Marlon Rigg’s 1989 film “Tongues Untied.” As they discussed their own relationships to Blackness, to sexuality, and to the film, Ross asked questions of the audience like, “When has anger silenced you?” and, “What makes you feel alive?” The conversation was interspersed with poetry and music; in one enchanting moment, all five stood up and danced freely with their tongues out. In each transition, Ross gave gentle but firm directions to turn the lamps on or off.

Ross’s conceptual exploration of the eclipse began with a 2014 video project entitled Eclipsing (body), and the festival was initiated by a curatorial residency at the performance venue Links Hall. As Ross began compiling a list of artists to include, a concept for an exhibition began to unfold, and so Ross turned to additional art venues that could support the work with both space and funding. The Arts Incubator — cornerstone of the Theaster Gates-directed, University of Chicago-funded “Arts Block” in Washington Park — housed the group exhibition, while ADDS DONNA hosted Jomo Cheatham’s solo exhibition.

Despite the scale of the festival and its institutional partners, ECLIPSING felt homegrown. Ross, who co-runs (and lives at) the domestic art venue F4F, is a lead artist for the Teen Creative Agency program at the Museum of Contemporary Art, and attended the School of the Art Institute, is no stranger to navigating Chicago’s large art institutions while grounding in a DIY ethos. Institutions often require many routes of navigation for the individual artist or curator: their internal bureaucratic systems and hierarchies, their metrics of success, their neighborhood politics. But for Ross, it was important to find organizations that could support free or low-cost programming and pay the Black artists and artists of color who worked on the festival. We discussed this further over sweet potato pie at the Currency Exchange Café.

Sasha Tycko: How was the working relationship with the Arts Incubator?

Amina Ross: Very collaborative. Just a hundred percent supportive. In my work navigating other large institutions, I feel like a lot of that work or labor comes in where you’re asking for permission, or proving why you need this, and that wasn’t the process at all. Which was like, “Wow! You have money and you’re letting me do what I want to do?!” Shit…So that whole labor of navigating institutions was erased from the process, and was very much a bunch of people coming together to figure out how do I support this work. Even Gabe Moreno, who’s the preparator for [the Arts Incubator], built a custom rig for the projector. One of the artists, Shala Miller, wasn’t available and doesn’t have an assistant or someone to fly out and install her work for her, and Gabe was so passionate about the piece that he poured everything he had into realizing that work and spent countless hours on making sure everything was aligned and just literally making the work. And that wasn’t anything he had to do. And there were a lot of moments like that, where the things that they didn’t have to do, and not even it being driven by some sort of perfectionist drive, but a drive to be like, “I believe in this thing, and then how do I make it work? How do I make it be the best thing it can be?” And that’s a really beautiful thing.

ST: You used the word “disruption” earlier. Do you want to expand on about that? What ways were you disrupting the institutions you were in?

AR: Yeah! Totally. I think that one thing I really appreciated from day one — and really, not a credit to the university at large as much as it is this specific team. From day one when we were discussing programming — because programming’s really important to me — they were like, “We’re really interested in things that people who live on this block want to go to.” And a lot of places don’t say that, and wouldn’t say that. And beyond it being just said, that sort of run is a part of everything we’ve been doing. And so, for me, it was wanting to create a series of invitations in the exhibition to the outside. And I think you can see a lot of that from just beyond the window. So I think typically the way that gallery space is curated is for the person inside of the space, but I really thought a lot — and I co-curated with Justin Chance as well — thought a lot about how we were catering to the person on the other side of the glass window. So some of those things were the piece by Kelly Lloyd, the big mountain landscape, and that was one of the first things to go up, and people would be like, “Who? What is this?” And people would peer in, and people were telling me — [people] who worked at the Currency Exchange [Café] and the Arts Incubator — that people were slowing down their cars. And so, for me, it was, “How do I cater to the eye outside the window?” And same with Cream Co.’s work, the plants that are installed along the —

ST: Yeah, I loved that.

AR: Yeah, that’s been the biggest invitation for folks. I’ve had a lot of people peer in and be like, “Oh, I garden, too, da-da-da.” And so people can take the plants home as well. So the idea that — one, that’s just super accessible. Who doesn’t love plant life? But also, who doesn’t need that, especially in urban landscapes, and specifically in urban landscapes that are deprived of the big budgets that Michigan Avenue is given to, you know, create these elaborate floral things that you see — it’s like, “Oh yeah, let’s curate all of this really peculiar plant life for people while they’re shopping.” But that same investment is not poured into places where people, specifically Black people and brown people, are living. There’s this absence of green. So wanting to also insert green and life into the space in that way and invite people to take it home with them. There’s something about care, like the care that the plants require as well. So those works specifically, for me, are huge invitations. And then I worked to also create a lot of programming that are invitations, and everything’s free. But yeah, thinking about the show as specific invitations for the eye beyond the window is a big thing.

ST: I want to break down more the process of curating and bringing together all the artists that you brought together. Because you describe it in a really intuitive way, which I think is cool. Even, in the intro to the catalog you say, “This felt good,” and that’s how you moved —

AR: Yeah, I move with a philosophy that all of my research will indirectly affect the decisions that I’m making, if it’s integrated into myself. So I do a lot of research, and just through moving as I am holding this knowledge, that research applies tangentially to everything. So I go to a lot of shows, I’m really interested in lots of things, but all of that is a long way of picking things up. So I started to think about eclipsing, I had some artists in mind already and just started listing. And I’m interested, with the performance festival, in artists who I saw working in ways that were very visceral. I also have a specific interest in technology and the way that specifically Black artists and artists of color are taking on technologies — whether that is Danny Giles’ interest in surveillance technology, or A.J. McClenon and Jared Brown, and even FUPU’s interest in audio technologies and the manipulation of audio. But taking on technology almost as a sort of form of magic, in processing either their own emotional landscape, histories, or the world around them, and either navigating their own internal power or the powers that are around them. And oftentimes, in dialogue with both of those things. If that makes sense?

…I also wanted to make sure I was leveraging power and like, “Are all of these artists from SAIC?,” where I went. No. That was a big thing. I’m not just going to be putting on all of my friends in that direct way. I’m not here for like “new nepotism” [read Sixty’s article on “new nepotism”] just as I’m not here for “Black capitalism,” it’s still the same shit. So let me make sure that I’m doing my homework and researching and then trying to pull them here. But from there, once I had the list, I worked with the artists pretty directly through the process of realizing the work. So we had a lot of conversations. I try to have dinners with people. Jared, A.J., and I had a critique at the house, where we all shared work with each other.

ST: Oh, that’s amazing.

AR: Yeah. But a lot of that sort of sharing of ideas. But most of the work was new work from folks. Not everyone, but mostly everybody. And all of the work was adapted specifically to this space. And so, I do like to have conversations moreso around the ideas they’re having, but then how that work actually looks is a bit of a mystery to me. So on the day of, I welcome the artists to take liberty with what — like, I trust them, there’s trust there, and I think that comes from the relationship building part.

ST: Right, right. Why did you pick the festival form? As opposed to — well, maybe that’s not a good question.

AR: No, that’s fine.

ST: Maybe that has an obvious answer. I’m just really drawn to that word here. Because it could be, it’s a “performance series,” or it’s a “show.”

AR: It took me a long time to think of the word “festival.” One, I think there’s something about celebration that I wanted to be at the heart of this. And it’s funny, because looking at the catalog — like, if you look at the text of the catalog, or you even just look at the titles of a lot of the workshops, or maybe even just with a lot of works individually — there’s a lot of pain and sadness. Like a tremendous amount. And, I don’t separate that from our joy. I think that oftentimes Black joy and Black pain are, you know, put on this binary of like, “Our joy is over here, our pain is over here. You need to leave the pain behind in order to be joy. Don’t be won by the falseness of joy. Sit in your pain.” Well, they’re all here at the same time. That’s how it’s embodied. So how do I create space for that in the showcasing of these works?

So I think “festival,” just sort of the connotation of joy there. And also, just wanting a multitude of platforms. It’s, one, just how I think and work. I’m just like manymanymanymany. Also well. Many but well. Do a lot but do it well. But I want to allow darkness and Blackness a space to be many things. And all at once. Which is why this idea of overlapping programming, and we had workshops that were on the same stage as the performances, so we’re going to be unpacking sexual trauma on the same stage that you’re going to be dancing later tonight. And really wanting to conflate these spaces to allow… It all, for me, is just an attempt to get at a holistic picture, that isn’t simplifying or forcing a body into a box. You know? So this was the best way I could see at just trying to get there. And it’s all an attempt. Because to really try to land at any absolute picture, to me, is not the idea, but to strive for it, you know?

ST: Right. You mentioned, at Threewalls, you said, “the personal is political.” Which feels really relevant to all the themes in the festival. But, how did that come out specifically? Both in the works themselves and in how people interact with the works?

AR: Yeah, totally. I think it’s like…yeah, I think that’s just a part of feminism or womanism that a lot of the artists embody. They’re incredibly well-researched, incredibly — all of the artists I’m working with know the form that they work within. So it’s not any sort of… Because I know there also can be the sort of reduction of Black artists, to like, “We’re just feeling our way through it!”, right? But we’re feeling and thinking at once. So they’re incredibly well-researched, incredibly aware of the forms and mediums they’re working in, and realize that their lived condition is the lived condition that contains, or contains within it, paradigms that mirror the systems at large.

So I talked about this specifically in the night that Gabrielle Civil and A.J. McClenon performed, in that they do a wonderful job in particular of using their own body as a site to mine collective trauma, collective joy, and really taking instances from their own lived experience and then unpacking, “What are the power dimensions at play?” And I think that that is, for me, that feels like a really effective way of furthering conversations around systems and structures that can get too abstract too quickly. Like, way too abstract too quickly, when it’s a felt thing. I feel it every morning, you know?

ST: Yeah. I have a question jumping off of that about senses. Visibility and seeing are obviously a huge part of the festival’s themes, but also I liked how other senses were engaged — like in Cream Co.’s piece, it says, “Touch. Smell.” It’s directing you to use those senses. So I’m wondering how, either in your own personal experience throughout the festival or in the works themselves, different senses come in, in addition to vision.

AR: Totally, totally. I think one thing for me is that I think a lot of conversations around power and identity politics oftentimes go towards visibility. And we see a lot of tactics employed to increase visibility. Which I think is partially effective, and is one strategy, and is not one that I’m like, “Oh, fuck that strategy, this is the way.” I don’t believe there’s the way, I believe there’s many ways. But I do think that’s perhaps the dominant narrative around identity politics, right? And liberation. But I think that there are other ways beyond being seen that are, for me — Yeah, I wanted to explore other ways beyond being seen. So, a large part of this festival — even thinking about the metaphor of the eclipse and what it is to find power based in darkness — means where do we find power beyond being seen? And so wanting to engage other senses was a big, big part of that. Like, what is it to feel somebody? What is it to smell someone’s pain?

ST: So the tagline for the festival was, “politics of night, politics of light.” I’m wondering if you felt like those were evenly treated, or if one —

AR: Mmm. It’s hard to treat night. Night is a marginal space. And I want to engage that. Like, to break that down a little bit: business hours, that’s daytime, like what happens at night, most of the times the things we associate with happening at night, are those of like — I think that’s even a saying, “All of the things that happen at night…” or “…the things that happen in the dark…” — but even the things we associate with happening at night, like, are sex and drugs — that’s on the fun end — and then on the not-fun end is like, “Who knows what’s going to happen when I’m walking home when it’s dark?”

And so I think it was hard. That’s a challenge — that’s a great question — because that’s a challenge that I want to lean into more, like what would it mean for me to have something that starts at 1 in Chicago. That doesn’t happen often here. And that is something — I was engaging that idea with wanting to bring in — I brought in some folks who work in nightlife who I really admire, specifically Trqpiteca [a queer DJ collective that played the after-party for the opening reception] and then Hijo Pródigo [the DJ who played the after-party for the closing reception]. And that’s my poke. I’m like, “I’m gonna step into it. I’ll figure out ways to support you because I love the work that they are doing at 4 in the morning — I love it — but my ability to engage a wide range of audiences that aren’t between, like, 21 and 30, at 12 in the morning— [laughs]

ST: Yeah. And then, even with light, I mean, it feels like it’s almost more the politics of dark than light.

AR: Mmm hmm. I wonder if darkness has a politic. If that makes sense? Like, that’s a good question, too. But I approach darkness as a felt thing, as a lived thing, as an experienced thing, as a time and space where we have the ability to construct our own rules and set of circumstances and environment. And, for me, light is the structure that is imposed on me.

ST: Yeah, light’s the agent. In the metaphor of the eclipse.

AR: Yeah, exactly. And so how do I address those politics while, you know, embracing dark space and time as a place of play and wonder and spirit and communion? If that makes sense? Which I guess is — there’s politics to that, but it’s a felt thing for me, and has been a very felt thing for me in the festival.

ST: Yeah. Could you just say a little bit about what you mean by politics? It’s a big question.

AR: Yeah! Totally, totally. You know, I’d love to also go and look in the dictionary. I do that all the time, but I find it’s really helpful.

[Amina looked up the term in the dictionary on their phone and read out a set of definitions for “politics”: “The activities associated with the governance of a country or other area,” and “The debate or conflict among individuals or parties having or hoping to achieve power.”]

And yeah, it feels to me like a sort of — and again, for me to want to engage the politics of darkness would almost be like wanting to — it’s the same way I was talking about the idea of “Black capitalism.” Like, what it means to attach a radical, felt thing like Blackness to a system that I’m not wholly invested in. [laughs] If that makes sense. I have to engage politics in my day to day, because, you know, I live in this world. And I do engage them. But I don’t aim to want to create a new set of politics of, like, a new system of achieving power, and power as it’s defined by this definition. Does that make sense? I really wanted to explore, like, a power that could reside in us playing, or a power that could reside in us making space for us to talk to one another. So, wanting to upend that power, rather than talk about, you know, how can we in dark space find this sort of rigid sense of power that has the ability to govern and order in this new way. Does that kind of make sense?

ST: Yeah, totally.

AR: That’s a good question! That’s a hard question.

ST: Yeah, sometimes I ask though because…it escapes me, you know?

AR: It’s important!

ST: It’s the sort of thing where it’s like, “Everything’s political!” but then —

AR: I do it all the time! I think it’s important to do. A large part of this is, the whole time, I’d go back to “What is Black?” I’d go back, “What is Black? What do I mean–?” For me, a puzzle that I return to a lot is, “What do I mean when I bounce back between ‘black’ and ‘darkness’?” Because they’re two different words. “Black” is a word and “dark” is a word. So I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about that. But even the smallest parts of our language carry so many connotations that, if I’m aiming to effectively communicate with you, we have to get on the same page.

ST: So if you were debriefing ECLIPSING, what are some of the successes and failures that you’re thinking about with the festival?

AR: The way that people have showed up for this project has been absolutely remarkable, and I think that’s been in part because the experiences that I’ve held space for have given them something that they needed. And a form of healing in whatever way that looks like. I think healing’s oftentimes reduced to looking like us putting our hands in a mudra of our choice and, you know, intoning in some way. But I think that healing looked like people moshing at FUPU’s set or looked like being questioned during Gabrielle’s performance or looked like singing “Coming Along” in Spanish during Joelle [Mercede]’s, looked like taking home a plant in Cream Co.’s. But that people were able to find things that either provoked something in them that needed to be addressed, that soothed something in them that needed to be soothed, that sparked something. That people were able to find what they needed and then have shown up for it. So that’s been really remarkable and, you know, to be able to hopefully do this again would be, [laughs] again, knocking on wood! We’ll see what happens! So, for me, the success is met.

I loved the question you asked earlier, though, addressing nighttime as a space — I think that’s the one where I really come up against some very material boundaries. And by “material,” just the reality that night is a space that people don’t like to occupy. So that would be really — it is an exciting challenge to me to see how I can push that more. I’d love to pay everyone more. [laughs] That’s a big thing. I’d love to also — as a big lesson — I’d also love to pay myself more, because I’ve been really horribly underpaid. I’m always like, “Oh, we need a photographer? Take it out my stipend!” “Oh, we need this? Take it out–!” “Oh man, you need this? Take it out my stipend!” And I think that also being conditioned as a Black person who was raised as a woman in this world, who has been socially conditioned in that way, can be very like, “Here!” So a big challenge for me is like, “Wow, can I do good work that is healing for other people, pay other people, and heal myself, which has happened, and pay myself.”

ST: Yeah. What surprised you? Or feel free to eat some pie. I’ll talk slowly. [laughs] But yeah, what surprised you, and how have your notions of queerness or Blackness or identity or healing been expanded or evoked?

AR: Totally. I guess just seeing intersectionality embodied communally has been really surprising and exciting. When we first started, and I was putting the workshops out, there was the question around whether I was going to keep them as affinity spaces, which I do with Beauty Breaks [an experimental workshop series founded by Ross that opens participation to Black-identifying people], and I wanted to really see like, “Well, what if I offer up the same thing and don’t put any caps on who could come?” …Do you know what I mean? So it’s been cool to put specifically Black femmes at the front of facilitating holding space for other people, or taking up space — performative space or visual space — and then having that also attended by other Black people, and also attended by folks who occupy other identities who are willing to show up and do the work and engage in harsh, in healing, in joyous, in painful conversation, activity, movement. That has been really exciting to me.

I’m always sharing the same headspace, or even being in the same headspace as older Black women who are mothers, like I’m always sharing that headspace, but to share physical space to engage in the conversation, I’m like, “Oh my god!” Or, like, I’ve always shared the — you know, I know a lot of Black, gay, male-identified people who share the same headspace with, like, me as a gender non-conforming femme person. But for us to share the same literal space and engage in conversation across those things has been so awesome. It’s allowed me space to embody a lot of the things I’ve been in conversation with through my object-based work or video work or things I’ve been reading or notes I’ve been jotting down. But to do that work with others has just been really, really awesome. To just engage in genuine discovery with other people.

Featured image: A still from Untitled (The Seed Sings a Secret Song) by Shala Miller, 2016. Video projection, soil, water, pigment. Image courtesy of the artist

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko and at www.nomoneynoborders.com. Photo by Julia Dratel.

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko and at www.nomoneynoborders.com. Photo by Julia Dratel.