Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates—through conversations with formerly-incarcerated artists and their allies—the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

In 1984, Vincent Wade was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison, based on a confession tortured out of him by Chicago police detectives. He spent 31 years in state prison, teaching and working as an artist in every available medium, sharpening his skills for the day he would walk free. On August 14, 2015—years after proof of systematic torture and coercion by the Chicago Police Department was uncovered—Vincent was finally released. While groups like Chicago Torture Justice Memorials continue to fight on behalf of Chicago police torture survivors, Vincent remains focused on the thing that got him through more than three decades behind bars: his art. We sat down just south of Washington Park to talk about Vincent’s artistic mentors, his fight to go back to school, and how freedom stole his peace of mind.

Michael Fischer: How far are we right now from where you grew up?

Vincent Wade: I’m gonna tell you something about this area. I practically came up in this area: 61st Street. We used to own a barbershop down there between St. Lawrence and Rose.

MF: You’re in a strange position of having grown up on the South Side and then returned more than thirty years later, without catching a single glimpse of it in between. What was the emotional experience of seeing the changes in your neighborhood when you got back?

VW: Well, to tell you the truth, now I see what the grand design was—what they’ve been wanting to do all along. This city’s being bought up in a blink. They took all those that had any kind of control in the neighborhood and just locked them up. They didn’t care how they got ‘em off the street; if they had to put cases on them, that’s what they did. I see how—from the senior Daley on down—they’ve concentrated on where to place things in this city, where to put the colleges, because they wanted Daley’s dream to come true—his vision for the city of Chicago.

I told my mother when I was in seventh grade that I wasn’t going to school no more. Long as I knew how to read, write, add, subtract, multiply, and divide, I didn’t need the rest of that stuff. And I really felt that way, because I had got so deep into the streets. I was like, “Man, I’ll have more money than a person working a nine to five every day,” and didn’t even do any work. All I did was allocate positions for guys and then, you know, collect. That was the lifestyle that was in these communities, those were the types of things going on in these communities.

Now that I’m back here, I look at everybody like robots, to tell you the truth. Because technology has them enslaved. People’s mindset is so small, especially in the urban community. They’re just glad to get by, day by day. And it hurts, because I was born and raised in this city. And it’s like, “This is what this city has become?” They took all that time in between away from me and my family—and mainly from my daughter because I only have one child. She’s grown now; when I left she was seven. Now she’s 38. I’ve got three grandkids. So it’s the psychological impact of everything that’s changed that’s hard.

MF: In prison, I assume there were times—especially in the early years—when guys came to you wanting things that were a challenge for you, things you weren’t sure you could do. How did the people you met inside help push your development as an artist?

VW: I met a Mexican guy in the county jail—I was in the Cook County Jail for two years—who couldn’t speak English. He couldn’t speak a word of it, but he would sit there and draw things that would just amaze me. I was determined to break the language barrier to get what knowledge I could out of him, and that’s what started me learning. I just watched him and started doing envelopes. And it got to the point that, by the time I got to the penitentiary, everybody knew me as an artist. Everyday Joes couldn’t even buy my work because of my prices. I knew my work was good; I didn’t have to force it on anyone. All I had to do was put it out there. I was an artist.

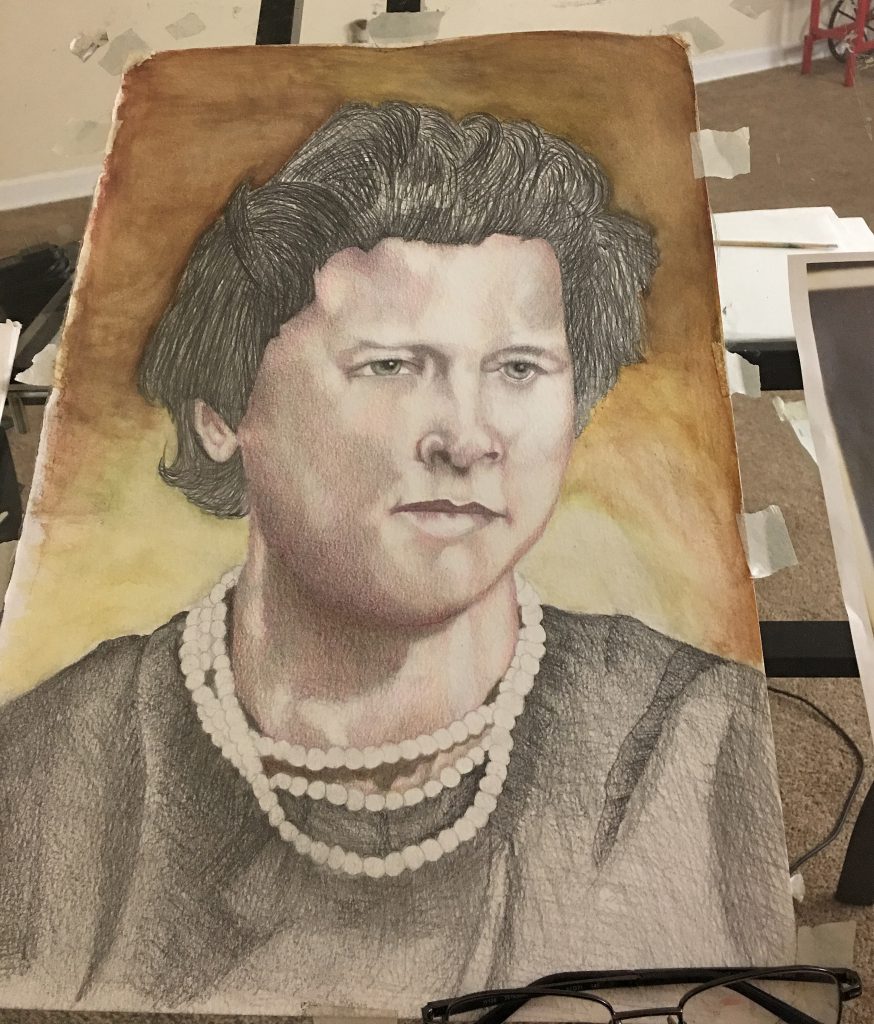

I have to give credit to Mr. Mark Merritt. He ran the Pace Art Program in the Cook County Jail back in the early 80s, and he’s the one who I give credit to for me actually learning how to draw. Mr. Merritt took me through every medium. He started me with graphite and then he took me from water-resistant ink to watercolors, from watercolors to acrylics to oil to pastels, then brought me back down to watercolors. He said, “If you can master that, the watercolors, there’s no medium you can’t do.”

Pretty soon I had the Ninja Turtles jumping out at you, Mickey and Minnie, all of that. Because you know, most animation is done in watercolors. So it gave me the true depth of color mixing. There’s a science to color mixing, especially once you get to portraits because there’s different pigmentations in the skin. You have to learn how to work with those different pigmentations, but they all start from a base. And that doesn’t come overnight; I made a lot of mistakes.

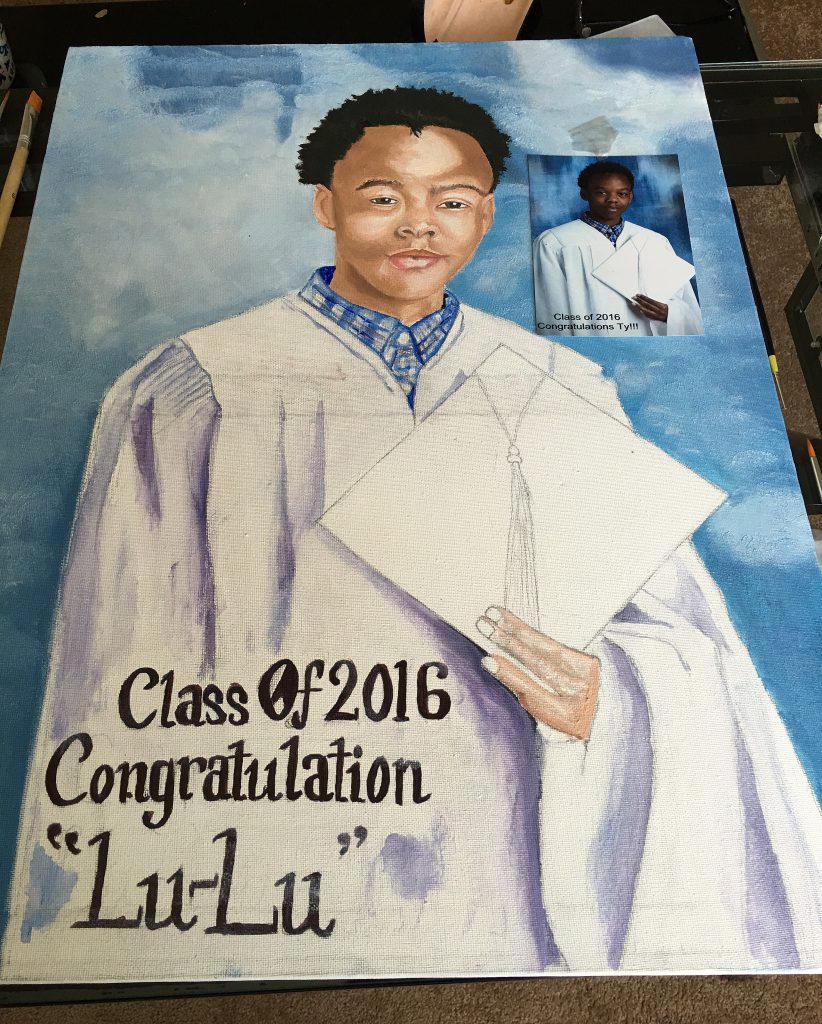

MF: Prison art is such a vital thread—sometimes the only thread—connecting inmates to loved ones. I remember commissioning a handmade card to send to some friends whose wedding I was supposed to be in; knowing they had it in their hands was the only thing that got me through missing their wedding. How conscious were you of that role, of being someone who could help bridge that distance created by incarceration?

VW: I’m glad you asked that. It came to a point where I became selective about who I would draw for. Because first you had to show me you had an appreciation for art—not that you just wanted me to do something real quick. And then, especially if you came to me wanting something for your mother or your kids, I used to give a lot more time and attention to those. Those used to be my best pieces. And I know I put smiles on a lot of peoples’ faces because I put my heart into things when I was doing them, I was never just looking at the monetary value.

As time went on, I would take it even further and try to be even more creative for them. I started making the hearts, making the roses out of papier-mâché, getting three-dimensional with it. Nobody else could do that but me. The creativity, the things I had to use—but I was still able to do it. I always knew my worth and the worth of what I did, and that’s something a lot of guys lose track of, being locked up all their life.

It’s not the monetary value that makes art art, by the way. Because what might not look like much to you might be a piece of art to someone else, and you’ll be looking at it trying to see what they even see in it. But that’s what makes art so versatile. I’ve learned that if you take the versatility of art and apply it to everyday life, you’re less burdened, less worried about things. And that’s how I was able to survive for so many years.

MF: At one point, you filed a civil litigation against the Department of Corrections; the prison you were in responded by confiscating your art supplies. How much confidence did overcoming obstacles—lack of supplies, lack of space, basically trying to create with one hand tied behind your back—give you moving forward in your work, now that you’re out and have everything back at your fingertips?

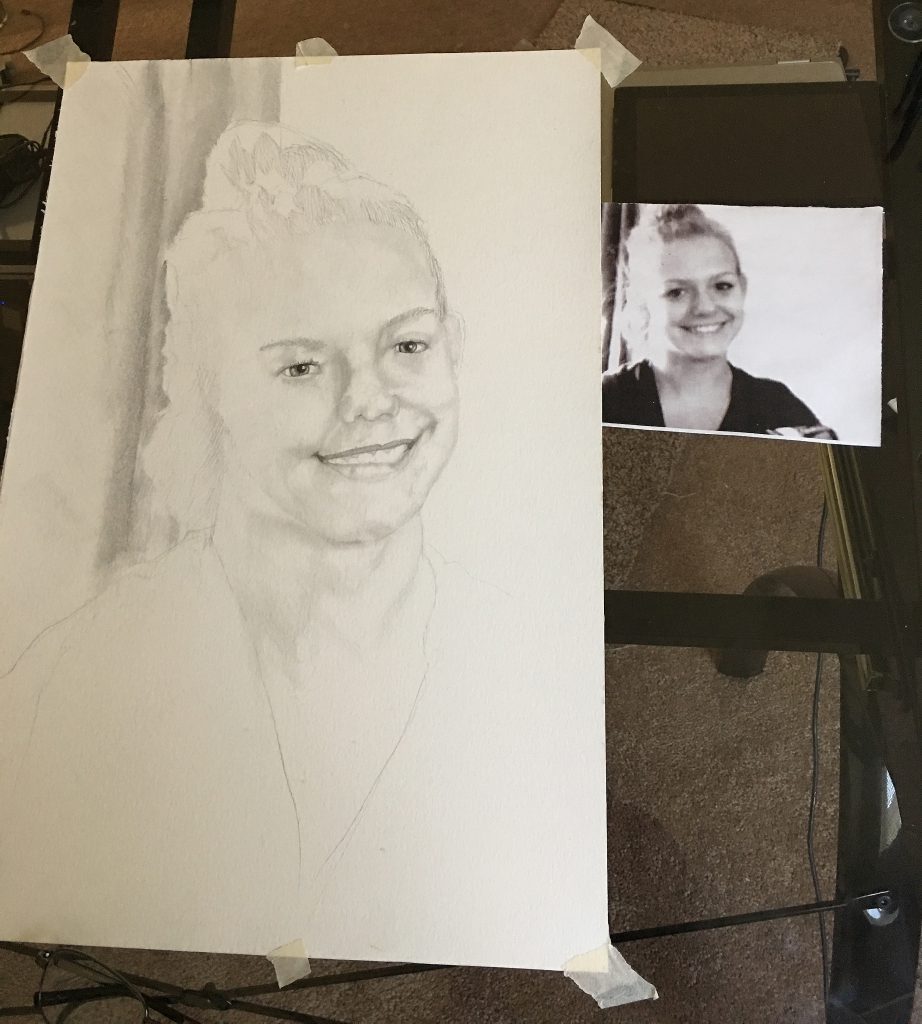

VW: I’m glad that I went through that, because at that point I had told them, “You can take my supplies all you want, but you can never take my skills away.” They had me in segregation for four years; I didn’t have nothing but a graphite pencil and a black ink pen. And I still was surviving, off of just that. People asked me, “How can you go to Seg and come out at 215 pounds? Everybody else goes back there and loses weight.” And I just said, “I’m loved by a lot of people.”

Guys knew they could buy those cards off the commissary and send them down to me and I would make something happen. And next thing I know everyone’s sending me work, even though all I can work with is a pen and a pencil. And that’s how I stayed fed. So now, yeah it’s easy. I can do anything.

MF: The lifers I knew, it seemed like anyone who had been in for 25, 27 years, or less was still pretty sane. Any longer than that, guys had lost touch with reality a bit—sometimes a lot. You did 31, yet here you are with your mind still intact. For anyone that doesn’t believe in the power of art as therapy, who thinks that kind of talk is woo-woo bullshit, talk a little bit about that.

VW: I’ve learned over the years that a person is quick to say, “I can’t do it.” Once you interject that thought into your mind that you can’t do it, then you can’t. I’m glad that I had the opportunity to teach art classes, back when they were open. All the guys I taught became artists, because I taught them the way that I was taught. I took them through the same channels that I was taken through. You might come into class and want to draw portraits, but that’s not what you’re going to start with in my class. You’re going to start with a still life. First you’re going to learn how to give an object life, to make it come off the paper with that graphite. Then we move on. The guys I had that paid attention to me and really took it to heart—came to class fully aware, didn’t want to play games, just wanted to learn what I had to give them—they knew what this work could be worth, how it could help you keep your sanity.

A lot of guys weren’t mentally strong enough for the changes that came about when the prisons went to total control of movement. Even segregation totally changed, the whole environment changed. Guys didn’t have anybody there to teach them; a lot of them were confused about the difference between a right and a privilege. Guys just didn’t know, and they suffered. I look at the changes in guys now: all the old guys in there don’t want anything to do with the newer generation, and the newer generation is just lost. They’re just lost.

I know what circle I need to be in to have my sanity. I need to be amongst people like me. I’m an artist, and everybody says we artists are weird anyway, because we see life differently. We go into an object, we go into a subject, we don’t just look at the surface of anything. Because as an artist, that’s how you dissect a picture. So that’s what I’m going to continue to do: stay on the path I’m on, but dissect things as I go.

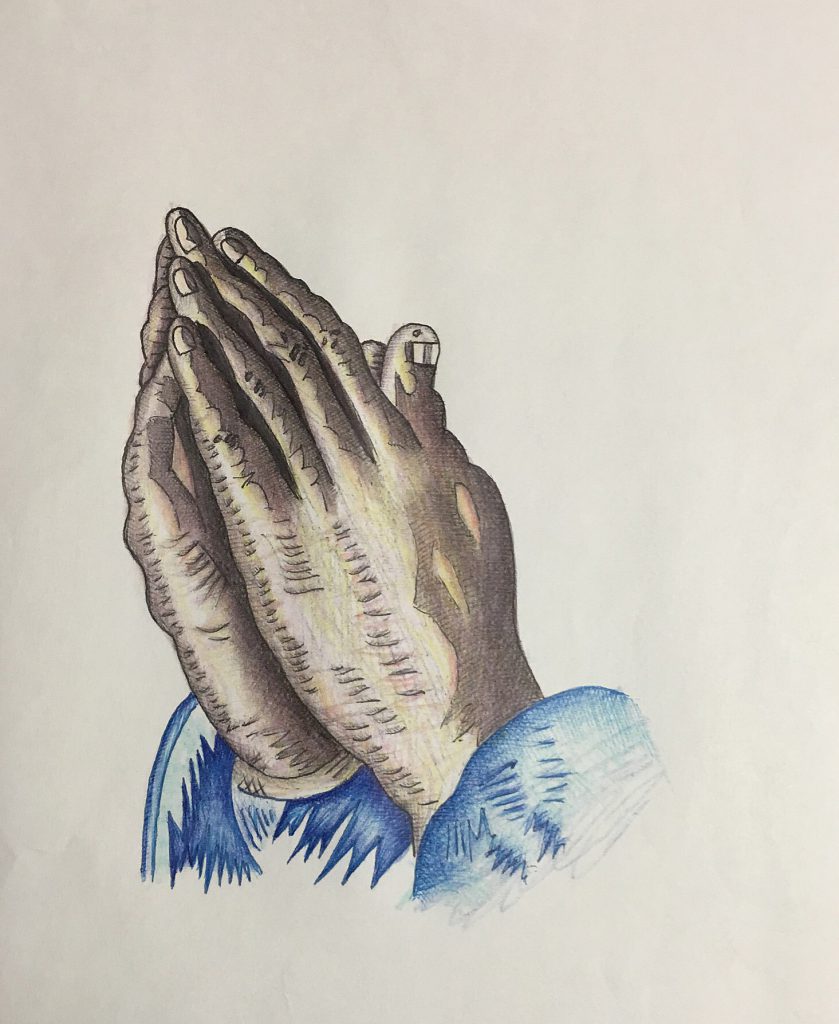

MF: You’re obviously a survivor, someone who embodies a positive mindset, but it must be hard not to look back at everything that was taken from you. You were raised Catholic and you’re now a devout Muslim. How have both your faith and your art helped you find peace of mind, maybe even forgiveness?

VW: I knew I was locked up for something I didn’t do, but I didn’t let the psychological effect of that keep me from bettering myself and becoming a better person. I take all my experiences, be they good or bad, and use them as stepping stones toward my future. And I actually had peace of mind inside, believe it or not, for 31 years. But now I’ve come home and my family has taken that away from me. And it hurts to say that, but they refuse to let go of the past. It’s the people that I’ve been meeting that I find more love and respect coming from than my own family.

I’ve been able to see what some of the people around me have set up as their god: money. I realized all they were focused on was seeing me on the news, people saying I’m going to get out and they’re going to give me some restitution money. But they don’t know the whole picture.

The psychological effect of what those people did to us and our families—all the money in the world can’t put that back together. You took 31 years out of my daughter’s life, and now she doesn’t want to forgive me. And then when she sees that I might raise my voice or something, she doesn’t want to be around me. And that hurts a father. So I just have to keep showing her, after all the negativity she’s heard about me all her life. I can’t just tell her; I have to show it. So I’m looking for forgiveness from others as much as I’m trying to find it in myself to forgive.

MF: Nowadays, social media and everything that comes with it is a big part of marketing oneself as an artist. How are you adjusting to what is for you a brand new world of media? Is it something you enjoy or is it more of a distraction?

VW: I don’t really mess with the social media. I’m old fashioned; I still believe in the paper and I’m glad I still believe in the paper. But some of my friends are jealous of me because I learned all this new technology quick. Everybody’s amazed; I’ll be 55 this Friday. Most people my age wouldn’t even want to look at all this technology for the first time at my age. So everyone’s like, “You learned all these apps and that so quick?” And I’m like, “Yeah, I know it all. I just needed to get my hands on it.” I’d already read all about it while I was inside. I’m like a kid with new toys now, playing the games and all that.

MF: Now you’re looking toward the next chapter in your life: applying to college to complete an art degree. I read over that form you sent me, the “criminal disclosure information form” required by the art school. It’s two pages long. I was pissed just looking at it, and I’m not even the one applying. When you think about your goals for yourself as an artist, when you think about everything you’ve been through in life and everything you’ve learned—and then you look at that form: what goes through your mind?

VW: You know, I’ve been through the fire, the real fire. I applied somewhere else already and got denied; they asked for a criminal disclosure and I gave it to them and they denied me. The counselor from the school even went out of her way and called me on her own time to let me know she felt what they did to me was wrong—but that was that. I wish the selection committee would have at least met me, given me a chance to talk. Okay yes, that’s my past, but I’ve been held accountable for my past.

I even had to emphasize this to my own fiancée the other day. I told her, “Understand, they have me labeled as a convicted murderer. Do you know the magnitude of that? You know how many resumes I’ve turned in, everybody saying they’ve got a job for me, but when it comes right down to it and I check that box on the application they throw me on the back burner?” So now I found something else, another art program. I think it’s a better environment for me and they have the program I want: graphic art and design. Once I learn that Adobe software, I know I’ll be good.

I’m not letting anything distract me from my focus. I see so much distraction out here. That’s how people get lost. I see how people steady looking at their phones all the time out here now. Do you realize you could allocate that time to something productive? If you don’t have an entrepreneurial spirit out here, you’ll cease to exist. You can’t be lazy. Scripture says so: “You must labor in order to prosper.” Nothing is going to come to you. You’ve got to make something happen.

I’m just going to continue to take it one day at a time, like I did inside. Tomorrow isn’t promised to you. At the time I was in prison, you better not expect another day, because you didn’t know if you’d live to see one. You didn’t know what was going to happen when you stepped out of that cell every day. My art took care of me for 31 years. I know it can take care of me out here.

Featured Image: Vincent Wade

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.