In 2015, I conducted ethnography across the United States, interviewing 100 people of the last analogue generation, to answer the question: How has the high-tech revolution changed us? In this work, I sought people of all backgrounds—immigrants, Indigenous, blue collar, white collar, rural, urban—asking them for their stories, experiences, and sometimes bald-faced opinions about the computer technology that had (and still was) transforming all aspects of American life.

Though my goal was to remain neutral, I was personally pleased to document the inspiring stories of innovative women right in my backyard. I grew up just outside Detroit, the child of a white-flight family, with a childhood sheltered and sanitized. I didn’t know much about the big city, let alone the rest of the state of Michigan, until I galloped from the gate just after my 18th birthday. I was hungry to catch up and sought the lived experiences of others to do it.

As an anthropologist, I gulped down stories like my ancestors gulped homemade brandy in Croatia, ultimately leading me to those 100 interviews. Though I went far and wide—driving almost 12,000 miles in total—it was these three women who made waves in my home state that stuck with me. Three women who knew themselves in a way I hoped I would someday know myself and who demanded from me every iota of attention.

One of my first interviewees came through due to her proximity to my hometown. Harriet Berg insisted I meet her at the Wayne State Farmer’s Market in downtown Detroit. There were many properties named “Wayne State” around the city, and I am famous for missing the obvious while noticing the minutiae, so it wasn’t until I’d arrived that I realized this was a food truck court right smack dab in Wayne State University’s quad.

We were interrupted by people she knew throughout her interview. Though retired, Berg’s influence echoed across campus among the young and old. That’s where her story unfolded.

“I went to New York [City] every year for twenty years to study. There [was] nobody here in Detroit to study contemporary dance with. I couldn’t get the training here, and so I had to go to New York to study with the people who had the knowledge. I started very late. I didn’t start dancing until I came to Wayne. I had a teacher who understood that I had creative ability. I joined the Wayne State University (WSU) dance workshop, and I eventually became director and taught at the university.”

Berg wasn’t the only teacher I met who had wide influence across the state. Later in the course of my ethnography, I met renowned professor at Michigan State University, Penny Gardner, at her home in Lansing. She floored me when she told me she was a Playboy Bunny in her youth.

“I had been caught dating a member at the Gaslight Club [in D.C.]. I began looking for something else because I couldn’t [afford] to be suspended. I found out about this and went and auditioned to be a Bunny.” I wanted so badly to share her story of empowerment in my book, but being a Bunny—and discovering you are a Lesbian in mid-life—wasn’t relevant to my thesis on the high-tech revolution.

Then there was Grace Stinton. She, too, invited me to her home where I met her family. It was immediately apparent that she was the matriarch, but she ruled with a gentle hand, living up to her name. Everyone knew she was a boss, and everyone knew she had earned the title out of a mutual respect.

I was urged to interview Stinton because she had been a Rosie the Riveter during World War Two. What I hadn’t been told was that she took that job to put herself through college—the first in her family.

“Our mother was kind of a pioneer,” said Stinton’s daughter, Penny Landosky. “She was the first person from her town to graduate college. She worked to put herself through college. In 1968, she completed her Masters Degree in Special Education.”

“I worked summers,” Stinton told me during our interview. “And one year I worked [at] the American Screw Company. It was a wartime [operation] making rivets for whatever apparatus they used in the army and all the services. So that’s my experience as Rosie the Riveter.”

Stinton, too, had seen the ways in which art was created and shared evolve as she grew up. The evolution from radio to television stuck in her mind: “I can remember the first time I saw television was at my grandmother’s house. She had a television and we went over and we listened to it and watched it,” she reminisced.

The Michigan Arts

“I came [to Lansing, Michigan] at the age of 53 to get my graduate degree and to be a lesbian,” Penny Gardner stated as matter-of-fact. During our interview she told me of her role on the board of the Lesbian Connection, one of the oldest LGBTQ+ publishers in the country. I left with a subscription. That’s how conversations with her went.

Gardner wasn’t one to demure, to fit herself into a mold for her students at MSU. Instead, she stood as an example of authenticity. Realizing she wasn’t going to keep up with tech, she showed her students her vulnerability, and they loved her for it.

“I went to the University Without Walls for my undergraduate degree out of Oberlin College [which is located in Ohio]. What I learned [of technology] I learned to use [at] the library [as a student]. Then I went back five or six years later as a teacher [at Michigan State], and it had changed. Even as a teacher, I would take classes, but I really needed someone sitting side by side with me for whatever I wanted […] Then, as a teacher, I just decided ‘fuck it’[…] This is who I was… and the students were accepting of it. I think that [it was because I was] an old person. I think if I were younger, that they would not be [accepting]. I think they loved me. Many of them would hug me when the class was over, but I still think that ageism and technology is a gap,” Gardner exclaimed.

Berg, too, found herself frustrated with technology.

“If they can figure out fracking, why can’t they figure out a way to put cartilage in my knees!?,” she exclaimed during our conversation. She had danced her cartilage away, yet was still active, doing yoga to aid her body’s aging after a lifetime of leadership in the arts.

“[Dr. Hillberry] said to me, ‘Harriet, I want you to start on your masters, because … I’m going to nominate you for head of the dance department. [WSU is] going to have a College of Creative Arts.”

Unfortunately, he passed away before Berg could take the role.

“The man who was chosen to be president wasn’t interested in creative arts,” she explained. “He wanted a medical school… so the whole thing was dropped. So, if I continued, I would be in physical education. As much as I admire physical education for taking dance in, I said dance is an art form, it should be taught like an art form.”

Berg, adamant about the value of dance being taught with all the creative support it deserves, left WSU. “I went to the Jewish Community Center that was reorganizing at the time, and I was there for fifty years. I developed a dance department and had two dance groups. We taught all ages, from three to three-hundred, and I had a wonderful, wonderful time.”

Berg wasn’t just a trailblazer for dance in Detroit. She set the stage for women of the era. Her husband supported her throughout her career, providing an example to those she taught that women can have careers.

“In order for a woman to do something like that [in that time], you had to have a unique and irreplaceable husband. You had to have a husband who supports you. He’d stay at home with the kids on his Christmas vacation. He was a public school teacher and he’d stay home and take care of the kids while I went to New York to study: he supported my career every inch of the way.”

Stinton, too, was a teacher, spending her time with junior high students until she transitioned to a stay-at-home mom: “I found that it was financially better to stay home and take care of other children than to have someone take care of my two and teach.” However, her leadership in the arts continued beyond the schoolroom.

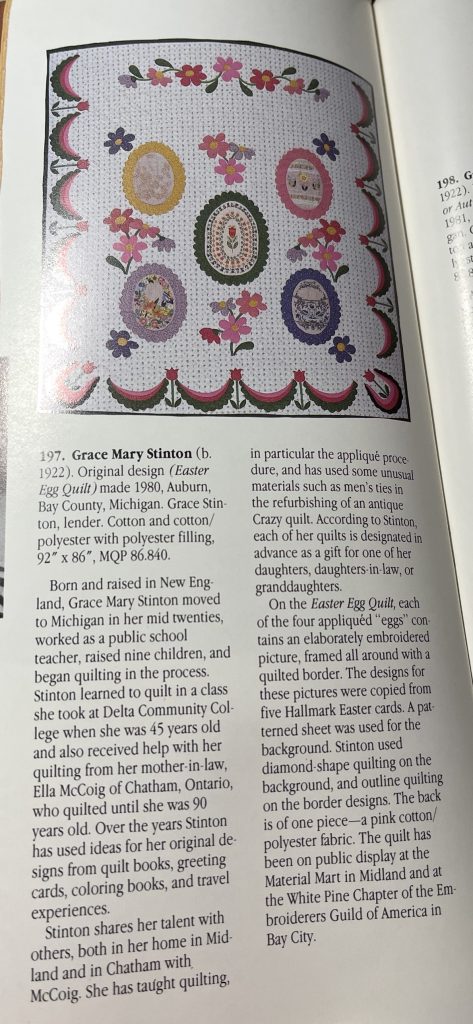

“[Our mom] created several quilts [whose titles] include Adam and Eve, I Dream in Chocolate, The Wizard of Oz, Look Ma! I Can Fly, Tempest Fuget ‘Time Flies,’” shared Landosky. “[She] also [quilted] a Hawaiian pineapple quilt, a pumpkin quilt, a Christmas quilt that included pictures of many generations, a beautiful Easter quilt, and many more. She designed every one of them.”

It’s no surprise that Stinton designed her works after fictional scenes. She was an avid reader in her youth.

“We had a one-room schoolhouse. [It] was open only on Wednesday afternoon and on Saturdays,” she said. “So I would go on Saturday, I would get there as early as it opened, grab all the Oz books I could read, take them home, go back before it closed, and get some more [to last] until the next Saturday—my pastime was reading and drawing.”

The Portraits

You would think someone like Stinton who had played such a pivotal role in both U.S. history and feminist history would have wanted her portrait to be taken with only her Rosie gloves. Not so. Stinton wanted her portrait to be taken with one of her quilts.

The family led me into the basement where, adorning the wall from floor to ceiling, was a quilt fully illustrating The Wizard Of Oz. The yellow brick road cut vertically, from Munchkin Land through the poppies and into the Emerald City. It was vibrant, full of life, and a grand example of just how Stinton had become known for her quilting and stitchwork, not just in Midland, but in national publications. “Grace was featured in Woman’s Day magazine with her pumpkin quilt design,” said her daughter. Her art influenced her family and community. Ever since, her influence has echoed to all she met. To this day, her family still keep in touch with me, even going so far as to write to me when Stinton passed.

Photograph of a page detail featuring a quilt design created by Grace Stinton. Image courtesy of Veronica Kirin.

Berg witnessed significant political action during her lifetime. She was ten years old when Diego Rivera, the famous Mexican artist, husband of Frida Kahlo, and Socialist actor, visited Detroit; her father organized the Streetcar and Milkman Unions in Detroit; and their family hosted Norman Thomas at their house while he ran for President of the United States.

“My [parents and their friends] were preparing a dinner for Norman Thomas. A friend of [my mother’s] was helping her peel potatoes, and Walter Reuther came in. He said, ‘Hi Helen, can I do anything to help?’ And she said, ‘Well, why don’t you sit down here with Maywolf and help her peel potatoes?’ They married, and were famous couple of the Labor Movement [across the United States].”

It was by Reuther’s statue at Wayne State University that Berg’s portrait was taken; a family friend, founder of the United Auto Workers union, and leader of the national Socialist movement which she continued to ascribe to.

Gardner on the other hand, would hardly hold still for her portrait. Rather, she eagerly showed us her inner sanctum: her attic, wherein she had written her thesis and proudly displayed posters from the protests she’d organized. “When I first moved here, my sister came shortly after… and she said, ‘Oh, this is such a good room. Don’t ever put anything on the walls.’”

She did.

“My pet project is abortion,” she pointed at one of the many posters lining the walls. “We did a march on Miami Beach. And this [desk] over here was where I wrote my dissertation. And this is a picture of my dissertation.”

Community at the Core

They each influenced their community as much as they were influenced by it. Berg changed the lives of hundreds of young women across Detroit, and built a program that continues to this day. She told me Missy Copeland was a modern inspiration to her: “It is an incredible story of a human being just overcoming every single obstacle they put in their way. She just wouldn’t quit wanting to be a ballerina. She is, like one might say, ‘the new rock and roll star.’”

Gardner advocated for women’s rights, mentored students, and was inspired by the likes of Mary Daly, Angela Davis, and Audre Lorde. “Daly wrote that you’re first in the foreground [dominant culture], and in order to be in the background [truth], you have to find yourself. So this is what I wrote about [in my dissertation],” said Gardner.

Stinton looked up to Caryl Fallert-Gentry, an internationally known quilt artist. “She always looked up to an artist named Caryl Fallert-Gentry. In fact, she purchased the tie dye fabric from Caryl from which she made her fish wall hangings,” shared her daughter.

These women shaped the arts landscape of Michigan in personal ways as active participants in their communities. Gardner cast her net across the national political sphere, Berg focused on her students and local movements in Detroit, and Stinton influenced the arts in both her public circles and within her family.

Landosky told me about her mother’s tradition of creating work for her family: “Grace Stinton, our Mom, was an artist,” shared Landosky. “She could take pictures from coloring books and reimagine them into whatever she was creating [at] the time. Her quilts are only a small sample of her talent. She was always creating things. In fact, she made over 150 beaded ornaments. She then purchased brass [Christmas] trees for all nine children and her sister’s daughter. We then proceeded to choose round-robin style from all the ornaments.”

I’m a firm believer in the butterfly effect—our influence does not have to be great in order to be wide. Each of us can have an impact through the arts, no matter the reach. This is important to note in a cultural era that belittles the benefits and necessity of the arts and uses it as an excuse to cut their funding, and the lives of these women serve as a great reminder of this fact.

* * *

In an effort to honor and preserve the stories and voices of our elders within our (arts) communities, Sixty is prioritizing interviews with the elders in our (art) communities. Are there elders within your Midwestern communities whose work has had a positive impact on your community and whose story has been unsung? If so, we would like for their story to be told! You can learn more about this publishing priority and pitch your story here.

About the author & photographer: Veronica Zora Kirin is the founder of Asterisk Women’s Health, cofounder of Anodyne Magazine, and founder of GreenCup Digital. She is also an anthropologist studying paradigm shifts, the author of the award-winning book “Stories of Elders,” and has presented her research at two TEDx events. Kirin has been named a Forbes NEXT 1,000 Entrepreneur, one of GO Magazine’s “100 Women We Love,” and a BEQ 40 LGBTQ Leader Under 40. Follow Veronica’s work @vmkirin.