This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago Now, an initiative by the Terra Foundation for American Art that amplifies the voices of Chicago’s diverse creatives, past and present, and explores the essential role they play in shaping the now.

Can the dead perform?

Supernatural, yet consider the case of one remixed mausoleum: Reckless Rolodex, an exhibition at UIC’s Gallery 400 dedicated to the memory of Chicago performance artist Lawrence Steger. Curated by Matthew Goulish, Lin Hixson, and Caroline Picard, the gallery’s antechambers hold a trove of archival material including photographs, posters, letters, audio recordings, costumes, and props from performances in the 80s and 90s, and a fruit cake made with Steger’s ashes that has circulated amongst his friends for the past two decades.

These are all means of contact with the dead, some more visceral than others. Pressing on and beyond Steger’s archive, the exhibit offers layered resonances and homages from a younger cohort of queer and trans artists, including new commissions from Devin T. Mays, Derrick Woods-Morrow, and Edie Fake. As Matthew Goulish’s curatorial annotations explain, “New forms emerge out of old errors, the reckless with the rolodex, and here we are extending them, extending the idea of you, as an invitation. Your methods, your personas, your mysteries, your aggressions, your sources, your intellect, your generosity, your conviction, your humor.”

“You,” as any torch singer worth her salty tears knows, is a porous pronoun. Goulish’s intimate second-person conjures the ghostly traces of Steger’s influence into the millennium he never saw, as the next generation steps in to fill his shoes. Collectively, these artists stage a new performance with Steger’s ghost. I left the exhibit with an eerie sense of kinship and identification with the artist through others, despite never having crossed paths with him.

WARNING: The author makes no assurances against the grave risk of courting the afterlife, of turning back like Orpheus to Eurydice. Performing with the dead is a reckless rolodex, a fatal game of roulette. Proceed with care…

Copy the moves: dance with death, dance with life. A repertoire is a personal history, a record of where you’ve been and who taught you or otherwise left an impact. Re-enacting someone else’s repertoire is like living another’s archive. Cherrie Yu’s video Trisha & Homer (2018) makes an effective use of split-screen as she mirrors the choreography in an archival recording of a talking dance by artist Trisha Brown (who died the year prior to the making of Yu’s video). Then Brown’s video disappears, but her audio becomes a voiceover for another custodial figure in the video frame. Homero Muñoz, a maintenance worker Yu met in downtown Chicago, sweeps a staircase between two escalators. Just as before, Yu copies Muñoz’s movements as if rehearsing choreography. Yu asks Muñoz—her psychopomp—if he thinks of his work as a performance. Muñoz answers in the affirmative (as would Brown, whose postmodern dance vocabulary celebrated everyday movement in public places).

Abridged description of the artwork courtesy of Gallery 400: color film begins in a two-channel format featuring two women in either frame cropped at the waist. Found footage of the dancer-choreographer Trisha Brown’s 1986 performance, Accumulation with Talking Plus Watermotor, plays on the left. In this frame the artist, Trisha Brown performs a series of movements in a dance studio, speaking slowly. On the right, is the contemporary artist Cherrie Yu. Yu replicates Brown’s dance and the two figures produce the same series of movements simultaneously. Brown’s voice alone is audible, even after the video switches to a single-channel format. In the next scene, the video resumes a two-channel structure. Brown’s voice remains audible. The left-hand frame features a public stairway running between two escalators (one up, one down). As people pass up and down the passageways, the camera remains centered on the back of Homero Muñoz mopping the stairs with a mop. Muñoz has short brown hair, wears navy pants, a loose navy jacket, sneakers, and appears to be at work. In the right-hand screen, the camera centers on the back of Yu in a kitchen. Yu wears the same black shirt and pants from the earlier sequence. She has no mop but reproduces the actions of the Muñoz in time with his own. The final portion of the film depicts Yu and Muñoz seated against a wall. They face the camera without speaking and move very little. Yu, on the left, wears a white shirt over a black tank top and glasses. Muñoz wears a black button up shirt with a white undershirt. They appear to be watching the same film,Trisha and Homer. Although Yu and Muñoz do not speak in the frame, subtitles capture their audible discussion about dance, labor, music, and performance.

The curator’s wall text likens Yu’s acts of mimicry to drag, one of Steger’s performance genres, though I might instead describe her video in terms of temporal drag: there is a “liveness” that is repeated and reenacted, supplanting the subverted role play. How does our understanding of this video performance shift if we view her homage as the living dancing for or with the dead; or the dead dancing through the living? Yu’s video is a layered form of Maintenance Art, as it braids the care work of remembrance and cleaning.

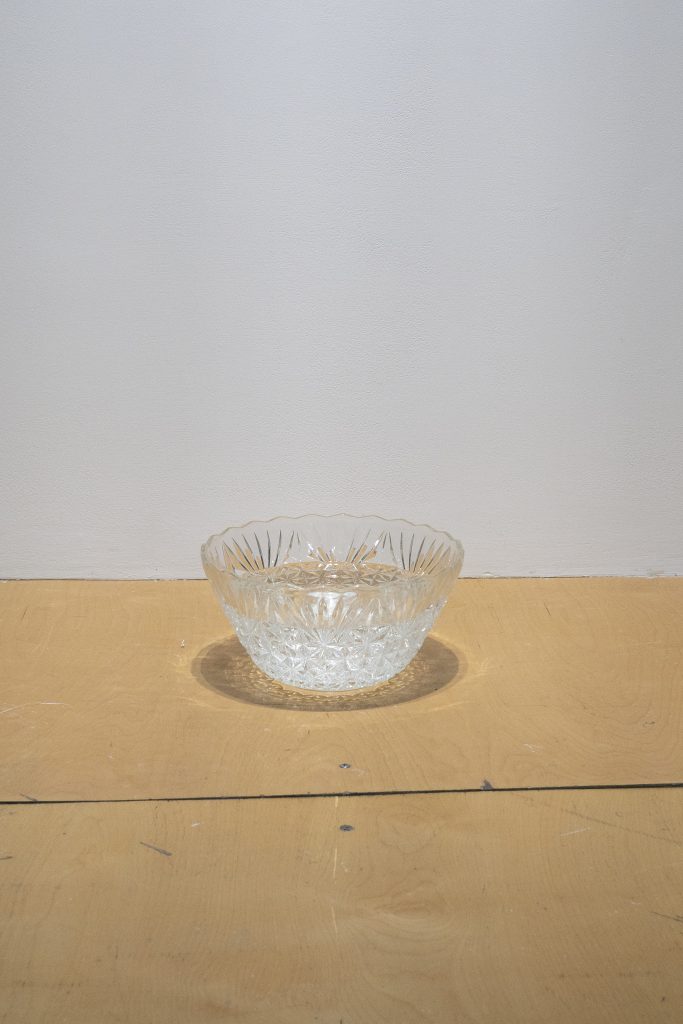

I linger on this theme of care as I consider the partially filled vessel of water sitting on the floor nearby, almost like a pet bowl. There are several other small bowls of water throughout the exhibit on the floor, from Devin T. Mays’ At Rest, a vessel (2023). In the corner, a letter accompanies a pitcher on a plinth, addressing the curators: “Dear caretakers…” Within the body of the letter, the curators are assigned the responsibilities of filling various vessels with water and maintaining their water levels throughout the exhibit. Hydration is essential for life, those in mourning (grief hygiene!), and maybe also for art, and the dead. In assigning this task of watering, Mays insists on a collaborative relationship with the curators. The curatorial role is one of care taking, not only for objects in a space, but also ideas, people, histories.

It is crucial that this activity is ongoing and not one-time: through repetition and attention, it becomes a ritual of presence, of what Christina Sharpe eloquently describes as “wake work”:

“Wakes are processes; through them we think about the dead and about our relations to them; they are rituals through which to enact grief and memory… But wakes are also ‘the track left on the water’s surface by a ship, the disturbance caused by a body swimming, or one that is moved, in water’… finally, wake means being awake and, also, consciousness.”

To stay in the wake requires care to sustain a co-present relationship with the not-yet “Past” and hold complicated feelings and histories. I’m conscious of the exhibit’s bringing Black and Asian queer and trans artists into dialogue with the archive of a dead, white, gay, male artist of another generation. Is it a discredit to these younger artists to frame their work in service of his memory? Yet the interposition of present and past, pulling towards and away from each other in a dance, enacts a compromise between the living and dead. At the meeting point of the water’s seemingly even surface: a reflection, a disturbance.

Nor is the viewer exempt from the responsibilities of care for the dead. Derrick Woods-Morrow’s Gravity Pleasure Switchback (2023) is a participatory ritual. Two upright twin used mattresses face each other, subwoofers heaving inside them, like lovers bearing marks of their histories—a motif which calls to mind Felix González-Torres’ work, especially the intimate undoing of public/private in his empty bed billboards. Nearby on the floor were white balloons of different sizes, to be blown up by audience attendees. Other “materials,” listed in the artist’s wall text, include “empathy, patience, and time occurring unnaturally.” These conceptual materials point towards the social and requires the participation of the viewer to complete the relation.

A poetic performance score on the wall bears an invitation to take part in a grief ritual: to suck your breath to fill a balloon and contemplate Dionne Brand’s Verso 55, a chiasmic poem of gratitude for Black aliveness: “The gods woke up and we felt pity for them, and affection, and love. They felt happy for us, we were still alive. Yes, we are still alive, we said. And we had returned to thank them. You are still alive, they said. Yes, we are still alive.” Like González-Torres’ seemingly innocuous candy piles, the balloons are a playful but ultimately elegiac vehicle for the exhaustion of breath, the circulation of life, of stillness, of liveness, of still alive.

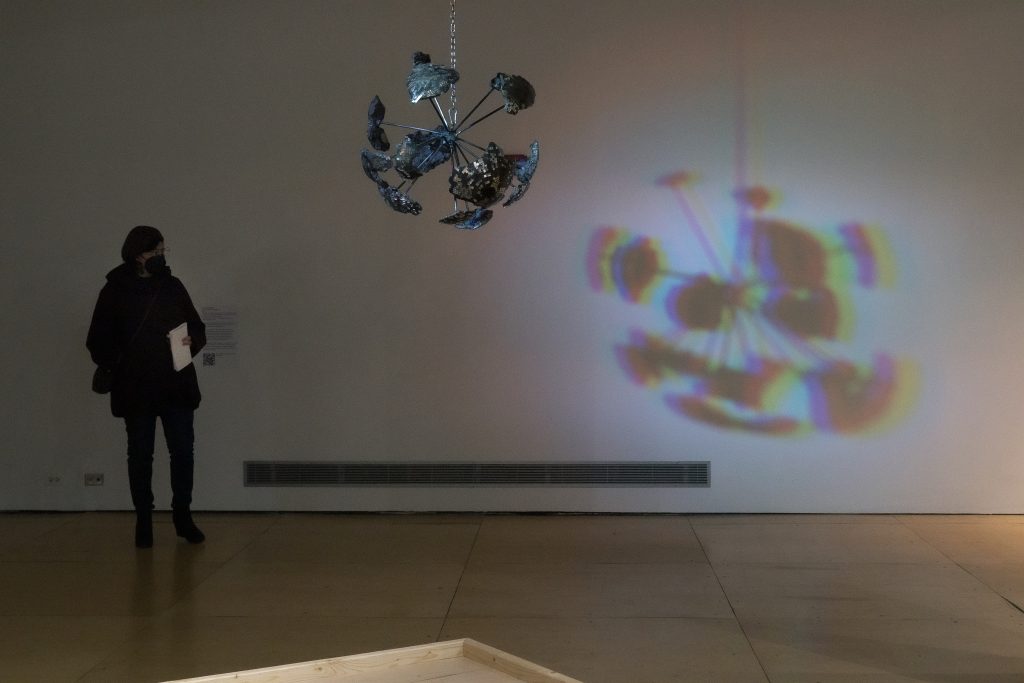

Yet we who are still alive sometimes feel left behind, wrecked in the wake. Will someone constellate our pain? Young Joon Kwak’s large hanging sculpture Brown Rainbow Eclipse Explosion (2017) looks like a disco ball that met a wrecking ball. Iridescent neon shards cast multi-colored shadows on the wall, light dancing. If the disco ball, as Jafari S. Allen describes in There’s a disco ball between us, is a constellation of mirrors reflecting and refracting “light at different angles, showing different colors of the spectrum—seemingly in a different time too, shifting on the walls, on the floors, on the face of dancers at different points in space”—then you or I might see ourselves in the wreck of the funeral disco, encounter the risk of our own shattering, join the afterparty.

For queer people, nightlife can be a site of sanctuary or refuge, even while it is also laced with grief. There are so many people no longer here to dance with us. The (after)party might be “a way of staying alive and of keeping each other alive,” as performance scholar Joshua Chambers-Letson elegized his mentor José Muñoz, “In your case, it was a way of sustaining your life after your death.” This context is all the more inescapable in the aftermath of an ongoing history of homophobic club massacres, including Pulse, Club Q, and the Upstairs Lounge. Not even to mention the ongoing, willful governmental neglect of queer people through AIDS, monkeypox, and COVID. Capitalism’s machinery grinds on despite and against us and gentrification’s selective amnesia of cultural spaces and histories leaves us to remember parties shut-down on our block, underground lifeworlds subsumed by yoga studios and juiceries. What spaces are left for us in the grief industrial complex?

Artist Edie Fake’s speculative drawings Memory Palaces pay tribute to the architectural details of closed Chicago night clubs and other lost queer places with ecstatic specificity. Fake’s commissioned piece for Reckless Rolodex, a 160 square foot wooden platform installation called Open Moment (2023), continues his interest in the potentiality of queer space, building on those histories to speculate what’s on the horizon. In Fake’s own words: “It’s always been about tapping into knowing that these things existed as a source of power in the future versus a nostalgia trip. Less ‘Boo hoo, that doesn’t exist anymore,’ and more like, ‘We have agency in the present to create a world.’ It’s an ecstatic drawing of space and bodies.”

Ecstatic, indeed: Fake’s playful people-sized board game (an anti-capitalist Monopoly?) at the center of the room is painted with geometric patterns, its open-ended form draws out a utopian impulse in claiming space and worldmaking. A moment may be an ephemeral unit of time, but it can also be a memorable scene of fabulousness—think of André Leon Talley’s or Mariah Carey’s use of the word.

Throughout the exhibit, Fake’s platform was activated for various special events, lively gatherings in the here and now for another world. One winter night, Open Moment’s long ramp became an accessible fashion runway for Rebirth Garments’ queercrip radical visibility. On Valentine’s Day, former partners Mark Jeffery and Judd Morrisey reunited as ATOM-R to stage a performance art seance called I Love the Dead. ATOM-R’s mixed-reality drag gestured towards props and scenes from Steger’s repertoire and ended with a sensually morbid video recording of Steger covering the Alice Cooper song of the same name.

What if the dead are choreographers, providing a score from beyond the grave for the living to enact? What remains for us: a disrupted, de\composition, seeking transfigured embodiment. Love the dead, remember the dead, care for the dead—they might leave you with one last encore.

This essay coincides with the event “Call and Response: Lawrence Steger’s Archives and Lasting Legacy” presented by Chicago Collections Consortium (CCC) on March 7, 2023. CCC Executive Director Jeanne Long joined Reckless Rolodex’s co-curator Matthew Goulish and participating artists Max Guy, Mark Jeffery, Devin T. Mays, John Neff, and Cherrie Yu for a discussion about Lawrence Steger’s influence on their work.

About the Author: Noa Micaela Fields is a trans poet with hearing aids. She is the author of the chapbook With, and her work has been published in Tripwire, Anomaly, Zoeglossia, Elderly Mag, Tyger Quarterly, and Sixty Inches From Center, among others. She is the Events & Accessibility Coordinator at the Poetry Foundation in Chicago and a 2022 fellow with Zoeglossia and Disability Lead.

About the Animator: Kiki Lechuga-Dupont is a multidisciplinary artist based in Evanston, Illinois. She’s inspired by visual memory and its capacity for emotion and perspective. Though her body of work ranges in subject matter and style, she strives to design pieces that evoke a sense of wonder and mindfulness. When she’s not working, she’s tasting teas, collecting cookbooks, and exploring new drawing techniques. Photo by Matt Austin.