It goes without saying that so much of the labor in an artist’s practice goes unseen, ranging from the countless hours of trial and error experimenting with a medium before getting it right, to the often mind-numbing planning and prep work when starting a new piece. However, there is yet another layer below the surface of this complex production that is inherent to the creative process: research. There is collection of information, images, and archives that happens even before any pen is put to paper, feeding and informing an artist’s body of work. Works Cited asks artists to uncover this part of their practice with us, sharing research materials such as essays, playlists, online archives, and tips on how to navigate them. In the spirit of open access, this column also serves as a resource in and of itself, as each interview includes access to these materials in the form of either reading lists or sharable links.

In this edition, I spoke with Mario LaMothe about his collaborative project Assotto’s Child at the Altar, which explores, elevates, and enacts the work of gay Haitian-American artist, performer, and activist Assotto Saint. LaMothe is Assistant Professor of Black Studies and Anthropology at the University of Illinois, Chicago, whose writing and research focuses on queer, Haitian identity and performance, as well as Afro-Caribbean religious rituals.

Reading List:

- Nou Mache Ansanm (We Walk Together): Queer Haitian Performance and Affiliation by Dasha A. Chapman, Erin L. Durban-Albrecht & Mario LaMothe

- “Documenting Spaces of Liberation in Haiti” by Josué Azor

- “The Legacy of Assotto Saint: Tracing Transnational History from the Gay Haitian Diaspora,” by Erin Durban-Albrecht (free access via JSTOR during 2020)

- Jaime Shearn Coan in conversation with Mariana Valencia

- Assotto’s Child at the Altar – Propeller Fund

- Video of Assotto Saint Poetry Reading

Christina Nafziger: Could you tell me about the project, overall?

Mario LaMothe: Assotto’s Child at the Altar is a project that I submitted to the Propeller Fund through Threewalls [and Gallery 400]. It’s a tribute to Assotto Saint, a Haitian-American author, and performer who openly self-identified as gay. He was really a renaissance person. Born Yves François Lubin in St. Marc, Haiti in 1957, he passed away in New York City in 1994 at the onset of the AIDS epidemic. His stage name Assotto Saint comes from Asoto, Haiti’s most sacred Vodou drum, considered a divine entity, and Saint, in memory of Haitian revolutionary hero Toussaint L’Ouverture. Assotto was part of this cohort of LGBT thinkers, activists and artists in New York, men and women from around the United States and other countries who created social justice work aimed at destabilizing homophobia, transphobia, racism, sexism, and more. They were proponents of having and living with intersecting identities: how one’s race, gender and sexual expressions, class, nationality, religion, physical ability, and other self-identifications cannot be disaggregated and are expressed in dialogue and/or in tension with larger societal systems. In my opinion, Assotto does not receive the attention his colleagues such as Essex Hemphill, Marlon Riggs, Barbara Jordan, and so many others continue to receive. I am interested in questioning for whom his legacy has been remembered and forgotten.

Assotto did amazing work and has a modest readership, and I’m one of those followers. I discovered his work after he passed away through his essay “Haiti: A Memory Journey,” which is included in the anthology The Butterfly’s Way edited by Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat. The anthology captures the experiences of writers of Haitian descent living in the U.S. and who invoke Haiti in their everyday life. I fell in love with Assotto’s essay because he was so loud and unabashed about his gayness––I mean, he called himself a “low-life bitch.” I recognized myself in how proud he was about his identities, how he not only spoke out against so many issues like homophobia and transphobia but also stood up to government officials, from local to federal ones. I wanted to figure out a way to celebrate him, and so I thought, what messages did he cultivate and communicate? How do people remember him now and how do they embody or live his philosophy or practice philosophies similar to his?

ML: The moment I found Assotto, I bought whatever I could find. I bought three copies of his anthology Spells of a Voodoo Doll, for instance. I directed two exhibits inspired by Assotto Saint’s legacy at the University of Illinois Chicago, where I am an assistant professor. But I also wanted to stage and embody some of his works. So I proposed a performance art show to the Propeller Fund in which I will stand-in as one of his children––in plain words, one of his kin and followers––who sets out to build an altar for him as a way to remember his legacy. What do I mean by altar? Think about a Christian church altar. But in the Africanist religions of Vodou, Candomblé, Santeria, you build or fashion an altar to honor an ancestor and/or one of the religion’s divinities. A person does so as a means to maintain a connection with their ancestor and the divine, and to fashion a portal between the human and ancestral realms. I will perform as a non-binary person (they/them) in the process of building an altar for Assotto Saint to seek his guidance. They read and embody Assotto’s work as a form of liturgy. Basically, they engage in a dialogue with their ancestor Assotto. It’s supposed to be a multidisciplinary project that includes narration, dance, songs, and visual media.

I named this person, this child/follower of Assotto, Femmot. I was born in Brooklyn, New York and I grew up in Port-au-Prince, Haiti where I attended an all-boys Catholic school from 1st to 11th grade. I was––I’m still a very curvy guy––and my classmates read me as feminine. They called me “femmot,” a word they invented to basically mean “little woman” or “woman-ish.” It was this disparaging word that was used to tease me and force me into conforming to the heterosexist and masculinist norms of being a Haitian male boy or teenager. With my performance art project, I want to recuperate and give new life to Femmot, what these classmates thought of me as a deviant male person whose body hosts feminine energies. In many ways, my performance will reflect on how a person evolves with and maneuvers through non-normative identities, behaviors, and practices as well as how their communities accept or reject their non-normativity.

Femmot will be doing a ritual to remember Assotto Saint, and to remember the joys and pains that LGBTQI people of color experience. Without minimizing the obstacles LGBTQI people like him confronted, Assotto wrote copiously about the joys and liberties he experienced, which folks outside of the LGBTQI community didn’t understand. That’s in a nutshell the scope of my project. My main collaborator is a wonderful Haitian-American mixed media visual artist Alexandra Antoine who was formally trained at the School of the Art Institute Chicago, and has traveled to Haiti and West African countries to enlarge her practice.

I was supposed to start rehearsing in June and then have an opening in December in partnership with the Haitian American Museum of Chicago. Now, given the restrictions brought on by the coronavirus, Alexandra and I are figuring if and how we can do a live performance or put the project out in the world in a creative and powerful format that people can access without gathering in person.

CN: Yeah. Accessibility is very precarious, nowadays. It’s just interesting to me that, although so many things have been postponed or cancelled, so many performances are now almost more accessible, because things are recorded and made available online when normally they’re not. Are you envisioning this project culminating in an exhibition?

ML: Yes. For this project, Alexandra will repurpose photographs of Assotto Saint and of myself as a child and adolescent into collages that will juxtapose or blur aspects of our lives and embodiments. I’m in dialogue with Haitian photographer Josué Azor to use his photographs of Haitian gay men and trans women, to also illustrate that Assotto’s children are numerous and thriving. In the original project plan, collages would adorn the performance space and the physical altar dedicated to Assotto. And every so often, maybe three or four times during the run of the exhibit, I had planned on doing a performance to activate the altar. That is, I would go through the ritual of putting the altar together, of speaking the words of Assotto Saint, of embodying his gestures, of commenting on some of the collages. That was the plan. Many performance works are available online and are more accessible now, and I agree that that’s good in a lot of ways. But there’s something also to be enjoyed and cherished, for instance, if you and I did this interview face to face. Likewise for my performance project.

CN: Yeah, I totally agree.

ML: It’s a different vibe. Our bodies are affected differently by live and virtual encounters. The call and response varies according to how you’re reading my verbal and non-verbal expressions, and vice versa. In a performance space, if you give energy to me, I give energy back to you. Not that this exchange doesn’t happen during web-based interactions, but we’re adding a portal and other elements that generate both gaps and opportunities. We’re in the midst of figuring out how to see and act and react to one another.

CN: Yeah, there’s those micro-gestures.

CN: Definitely. This happens during performances, too––especially in smaller spaces. It’s just so much more immersive. It’s great having it on screen, but there’s nothing like feeling that energy and hearing people whisper or breathe or gasp. It’s those small reactions of watching and experiencing a performance––those things culminate in a collective energy. Yeah, that totally gets lost through a screen.

ML: I agree with you that there’s also an opportunity that can come out of synchronous or asynchronous web-based performances or visual output. For example, if I were to do it live, it would be with a small audience. The space of the Haitian American Museum of Chicago in Uptown is small. It seats approximately 40-50 persons. So let’s say I do three performances, there would be a maximum of 150 Chicago area folks. If I were to transpose the project to a visual medium available on the internet and have it out there in the world, then it might reach a wider audience. As such, I’m seriously considering what that opportunity could afford me. But I also want to do it in a careful way that’s methodical and visually interesting and that could live beyond the necessities of COVID-19.

CN: Yeah, yeah, exactly. I feel like research, a lot of making and creating, can be so isolating. It’s very interesting to me when individual research becomes a collective effort, a group effort. The project description of Assotto’s Child at the Altar mentions a couple other people that are involved. Are they artists? I’m curious how they became involved with the project.

ML: Sure. The way I understand Propeller Fund is that it provides seed money to emerging artists. It’s a modest sum, but it gets you to experiment with a project. And as a collaborative project it needs to also include other Chicago-based folks. Alexandra Antoine is based in Chicago. I am also working with dancer/performing artist Roxane D’Orléans Juste. Roxane is Haitian Canadian. I was a touring manager for the Limón Dance Company in the late 1990s when she danced with the modern dance troupe. She’s currently completing her MFA in Dance at the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign. Another advisor is Chloe Johnston, who is a Performance and Theater professor at Lake Forest College. Chloe resides in Chicago and is well known in the Chicago ensemble and immersive theatre scene as a longtime member of Neo-Futurists.

It’s incredibly reassuring to have this roster of consummate artists by my side because the last time I danced in front of audiences was 2012. Since, I’ve done dramatic readings and lectures in which I do gestures, poses, and minimal movements. I’ve done that, but to perform without a script, I need the guidance of these allies. I’ll be front and center in this case, so I need all these people to help me craft a message and a performance that can reach its fullest potential.

CN: That sounds really exciting. So, let’s move backwards to the research stage of this project. Since Assotto’s work is so performance-based, were you able to read descriptions of those performances? Were there any audio or visual recordings? How were you able to access the actual performance aspect?

ML: Some of the research I did included going to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which is a branch of the New York Public Library system where Assotto Saint’s archives are housed. I spent time at the Schomburg Center, reading his works and notes voraciously. I analyzed Assotto’s thought processes, his sources of inspiration, and how he synthesized his ideas. I listened to a few audio files. Video files were not readily available, and if there were ones available at the Schomburg, they weren’t digitized and available to the public when I visited between 2014 and 2018. There are a few video clips on Facebook. You can hear his voice in a couple of Marlon Riggs’s films, and he’s featured interviewee in Riggs’s No Regrets. I watch these clips and films to familiarize myself with his mannerisms and embodiment.

I also have a colleague in New York, Jaime Shearn Coan, who is a PhD. Part of their doctoral research and work at the City University of New York Graduate Center included the creation of an open-access digital archives of all of Saint’s materials. Jaime collaborated with Assotto’s friends, family, and kin whose own personal archives contributed to the digital archives. I had the chance to see and browse through Jaime’s project and I’m really excited about the fact that this platform is out there, or will be soon.

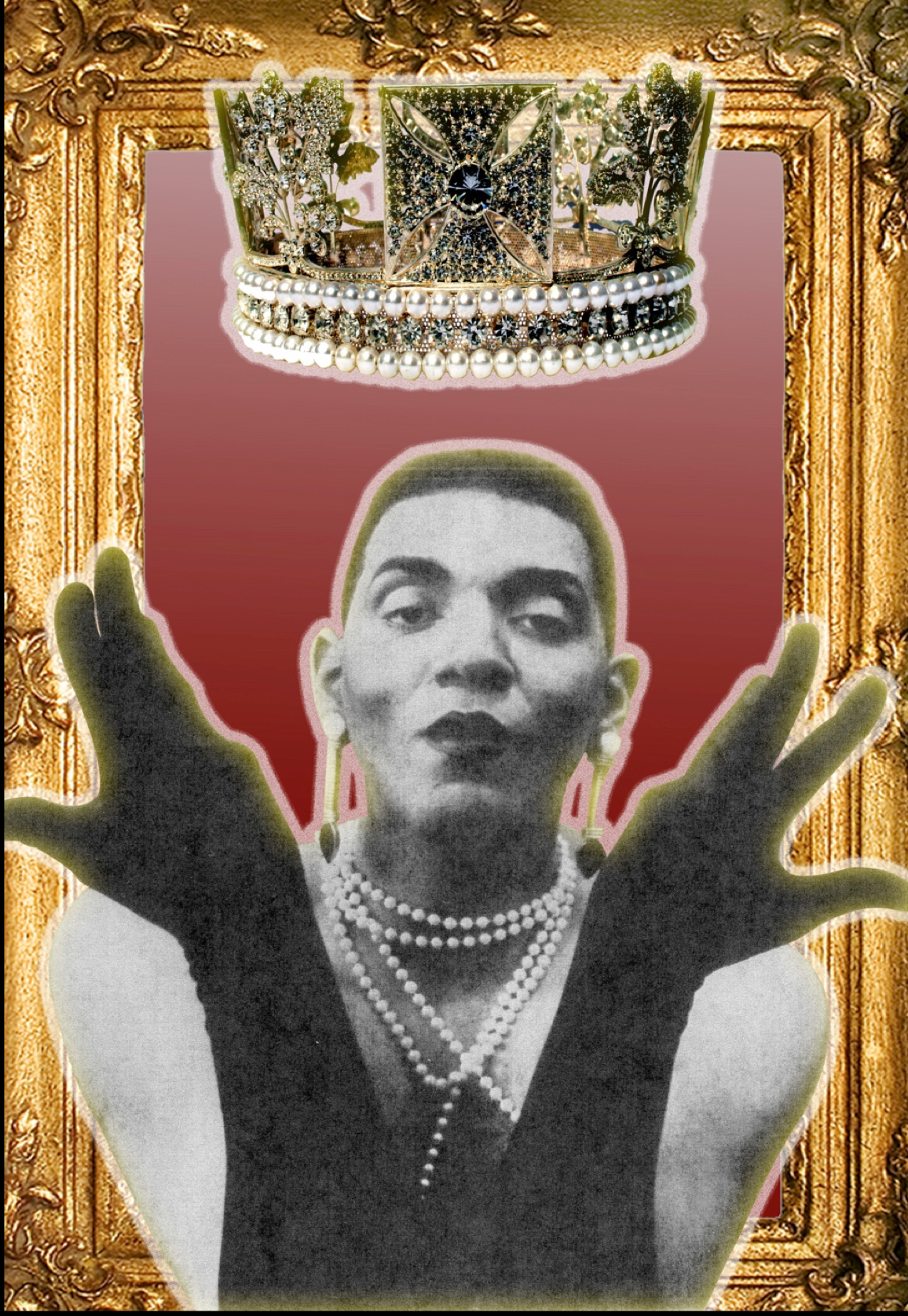

Video: A recording of Assotto Saint reciting his poetry.

All of these resources inspire me to re-imagine Assotto. For instance, there are two video clips on Facebook focused on Assotto reading a poem at his friend Melvin Dixon’s memorial service. He’s very expressive. He was also a dancer with the Martha Graham Dance Company early on in his career, and you can observe dance qualities in how he used his fingers and hands, moved his head, and carried himself. He loved to pose: to create a dramatic image of himself. My performance wants to improvise with how he fashioned and imaged himself. The idea is not to mimic him at all, but to use the traces he left behind as a springboard for paying attention to contemporary dynamics. The performance is about Assotto’s child remembering Assotto. However alike they might be, they are not one of the same. Much like you Christina, you might resemble your mother and share strong affinities with her. And even emulate her. But you can never be your mother. There’s something about your mother you know and/or respect well, and then you use that to project an idea of your mother.

CN: Yeah, and you interpret those qualities from your perspective. That’s a great analogy.

ML: Yeah, that’s what memory’s about: reinvention through working with what remains and filling in the gaps. We think our memories of an event are faithful, but the moment something happens and we think back on it, we start to reconstruct how that thing resonates with us. We’re not only interpreting but are making something anew. Remembering is simultaneously a creative and destructive act always, which requires a lot of imagination and ingenuity. That’s the beauty of remembering. What I’m hoping to do with this project is to merge Assotto’s voice with my memories as a queer, Haitian-American, and my experience with LGBTQI practices in Haiti and how queer Haitians create spaces of liberation for themselves there. Interviews I conducted with bi, gay, and trans women of Haitian descent for my academic research project are helpful in crafting Assotto’s Child at the Altar.

I have audio interviews, I have Assotto’s texts, I have my memories, I’m working with performing and visual artists. What can I and my collaborators do with these sources? Given the restrictions of the coronavirus pandemic, I can’t travel to New York or go to the Schomburg again. I have several tools. How can they aid me in producing a whole world? As one of my friends loves to say: the thing about art is that, for the most part, it’s always potent when we work with constraints.

CN: I think it’s interesting just to learn where people are getting their source materials from. You started talking about how Assotto’s Child at the Altar connects with your personal research––can you talk a bit about your personal research and how that led to this project?

ML: Yes, of course. To me it’s all connected. I have a couple of projects happening at the same time. From 2010 to 2015, I lived in Haiti to do research on my academic book project. However, I ran out of funding. To provide for myself, I had to get a job as a project manager for HIV/AIDS Prevention for men who have sex with men. I created a peer-to-peer education program for bi and gay men and trans women to communicate information on HIV/AIDS prevention best practices. I developed a network of HIV/AIDS education specialists who became my friends. When I returned to the US, we kept in touch and continued to collaborate. With academic and activist colleagues Dasha Chapman and Erin Durban who also research LGBTQI practices and activism in Haiti, I co-edited the 2017 special issue “Nou Mache Ansanm (We Walk Together): Queer Haitian Performance and Affiliation” of the journal Women and Performance. Our aim was to shed light on queer Haitian bodies who thrive, self-care and self-love despite or regardless of people and systems that oppress them. In many ways, I’m continuing that work with Assotto’s Child at the Altar. It’s a very organic process.

Additionally, since 2006, I’ve been attending Vodou ceremonies in Haiti, which are enclaves for LGBTQI folks. They feel most accepted there in Haiti, especially practitioners who are non-binary and gender fluid. For instance, let’s say a divine mounts you and wants to use your body as a vessel to communicate with the congregation. If that divine is considered primarily feminine and you are male-bodied person who self-identifies as fluid or a woman, for the span of that symbiosis, congregants accept you as feminine. You get to express your femininity. You get to be a woman and feel fully realized, so to say. It’s a little more complex and nuanced than what my example suggests and we don’t have the time and space to go into greater details. In any case, I go to Vodou spaces, I observe, I participate, and I do interviews with members of the congregation.

CN: That is so interesting! I didn’t realize how much research is conducted firsthand, like recording interviews in-person.

ML: Oh yeah, I consider myself an ethnographer. Ethnography is a research method that generates knowledge about how we live within communal and social structures. An ethnographer’s data comes from collaborations with human beings. It’s used in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. Your work and interaction with other people should be as dialogic and as critical as possible, meaning that you’re open to dialogue, to work through our various social positions and differences. You’re not poaching information. It’s a process of give and take with your collaborators. And hopefully by doing ethnographies with LGBTQI folks in Haiti or with queer people of Haitian descent, I’m also there to support them. I lend my hand, I lend my expertise. If one of my interlocutors wants to write a grant and they want me to proof it and translate it into English, I’ll be there. To listen to them talk about their joys and challenges, I’m there.

That’s my research method. It doesn’t dismiss who I am as a human being, my social positions, where I am in the world. The collaboration is not about me. it’s about being aware that my own way of looking at the world saturates the research. It affects it, it impacts it: I have to be very self-reflexive. I have to remind myself that I am a US citizen of Haitian descent. That comes with a lot of privilege. I can go to Haiti anytime I want and when I feel uncomfortable, I can hop on a plane. I leave my interlocutors behind. So, doing ethnography comes with a lot of responsibilities. It has to be grounded in really deep ethics for all involved. I’m in dialogue with others, and trying hard to balance out our power differences, privileges, and social stances as we generate critical knowledge about issues that affect our lives on a personal, communal, and societal level.

CN: Exactly. So, I have sort of a specific question. Looking at the description of the project on the Propeller Fund’s website, it says: “The project will simulate a Haitian Vodou rite of reclamation.” I’m wondering if you can elaborate on this because I don’t know much about these rituals?

ML: Well, let’s look at it this way: I think we all do our own rites of reclamation, in our own ways. Look around your house where you keep the things that you most treasure. We all build altars. Some of us might have a corner in which there’s a photo of your grandmother. Next to that there are knick-knacks, it could be like a ticket stub from a show that you saw. And somehow, those are all traces and mementos of something that you cherish the most. You feel this means something, it makes you feel whole and complete. It connects you to a past, and makes you feel grounded in the present. Sometimes, as a part of that set-up, there’s a candle we light. We burn incense there. For me, sometimes I’ll do a little prayer, like: “Grandma, I’ve been thinking about you today. Help me cultivate strength and wisdom today.” We may say a silent prayer. We sort of conjure the person into the space with us. It’s how we self-care, self-love, and self-heal. And those things are spiritual in the sense that it’s a way to nourish our souls. That’s how we do simple rites of reclamation.

CN: Yeah, definitely.

ML: An actual Vodou rite of reclamation is complex and involves ceremonial proceedings officiated by initiated elders. I’m not privy to the intricacies of such rites. In my project, I want to improvise with aspects of Vodou rites of reclamation I’ve participated in. Elements will include preparing the space for your communication with the ancestor: pouring libations, saluting the four elements (earth, wind, fire, and water), building an altar that reflects the ancestor’s taste and former aspirations. There’ll be prayers, orations, songs, and dances from beginning to end. In a rite of reclamation, one invites the ancestor to be their guide. In Haiti and in places where Africanist religions are practiced, once an ancestor passes away, the knowledge they have accrued in life doesn’t die with them. It transitions with them to the realm of the Invisibles.

In Haiti, after a prescribed amount of time (typically one year and one month) to allow the ancestor to reach the realm of the Invisibles and settle there, a human being is allowed to call the ancestor back, to guide the human from the beyond. That ritual enables your ancestor to remember how necessary and beneficial their wisdom is, to ask for clarity on an issue, and to understand how to better communicate with them. I don’t know if you can see––there’s a corner of my apartment where I have a mini altar.

CN: Oh yeah!

ML: It’s basically framed photographs of my loved ones who’ve transitioned: my great-grandmother, grandmother, grandfather, and father. And every once in a while, on Sundays or Wednesdays, I light a candle and burn some incense, I say a prayer like, “Thank you for creating me, for getting me here to this time and space, for me being here.”

I don’t want to be literal about a Vodou rite of reclamation. I want to personalize it. For my project, I’m claiming Assotto Saint as one of my ancestors. I want to say to Assotto: “You too are an ancestor of mine, as a Haitian American who went through a seriously oppressive time for queer bodies. The AIDS epidemic was destructive to that community. What did you learn that can serve me/us right now?” As a Haitian person growing up and being called femmot, I didn’t know I had role models who were queer, artistic, and passionate until I became acquainted with Assotto Saint’s works. I was shocked by and enamored with his artistry. There was a queer Haitian person who lived in the world and spoke frankly about his life and sexual practices and considered himself empowered? He said and performed these things? That’s what I want to reclaim: that queer Haitians are not abnormal and abject. We are part of a legacy, we’re part of a genealogy, and I want to claim Assotto Saint as part of that genealogy.

CN: That’s very powerful. It’s such an incredible project. I’m so into this. And it’s so true––thank you for showing me your altar. Yeah, that means a lot.

ML: And we all do it.

CN: Yeah!

ML: It’s like letting those ancestors know that they’re with us always. That’s what I want to do when I say “rite of reclamation.” It’s these things. It’s reclaiming the memory of these people by saying you are here with me always.

Featured image: A still from a video recording of Assotto Saint reciting his poetry. Assotto is in mid-word with his eyes closed while holding both hands to his body.

Christina Nafziger is a writer, editor, and curator based in Chicago. Her research focused on performativity within the image and the effect archiving digital images has on memory and identity. Her recent writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices as well as the role of the archive and its capacity to alter and edit future histories.