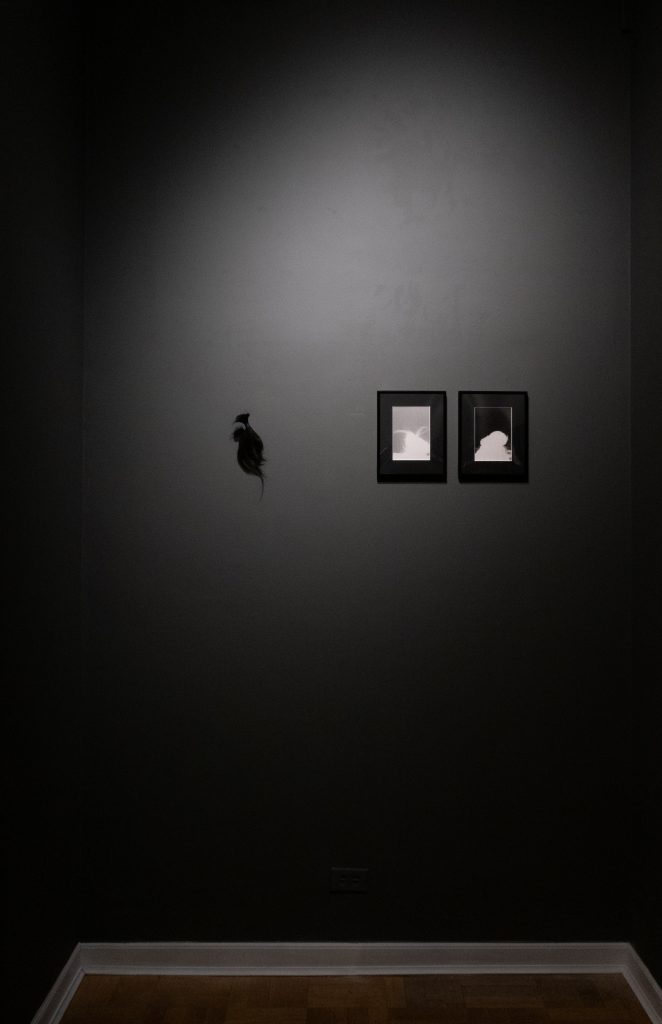

Photographer and musician Kioto Aoki uses a wide array of analog processes in her practice, such as pinhole cameras and cyanotypes, to experiment with photography at its rawest form. Her exhibition Breathe, Fibers of Papers Past at the International Museum of Surgical Science is the result of a residency she had at the institution last fall, during which she photographed and researched the museum’s history, translating herself and the architecture of the museum onto pieces of paper. When I visited the exhibition, I was surprised by how discreet yet poignant her photographs were. They are not all in one room, but rather merge within the museum’s permanent collection. Because of the nature of her work and how cameras operate with light and darkness, I noticed the reflections of textures and feelings more than I could make out clear images. The photographs are not quite abstract, since they include her hands or hair, but they often feel that way. The ghostly fragments of film photography wash away the faintest sight of a hand, only to remind us of the simplicity of the nature of photography: light entering a lens. Aoki turns these elements into poetic treasures.

For this interview, Kioto and I spoke on the phone to discuss her residency and process creating work for the exhibition.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mána Hjörleifsdóttir Taylor: Your artworks are scattered around the museum, often leaving the viewer to discover them, with no labels or descriptions. You merge your photographs with the permanent exhibition of the museum. For example, in one room dedicated to Japanese medicine, you display yourself on a plaque alongside doctors, as if you are one of them. It feels like a camouflage of sorts, almost like you want the viewer to not completely notice your work. What are you hoping for a museum visitor to experience from your artworks and this exhibition?

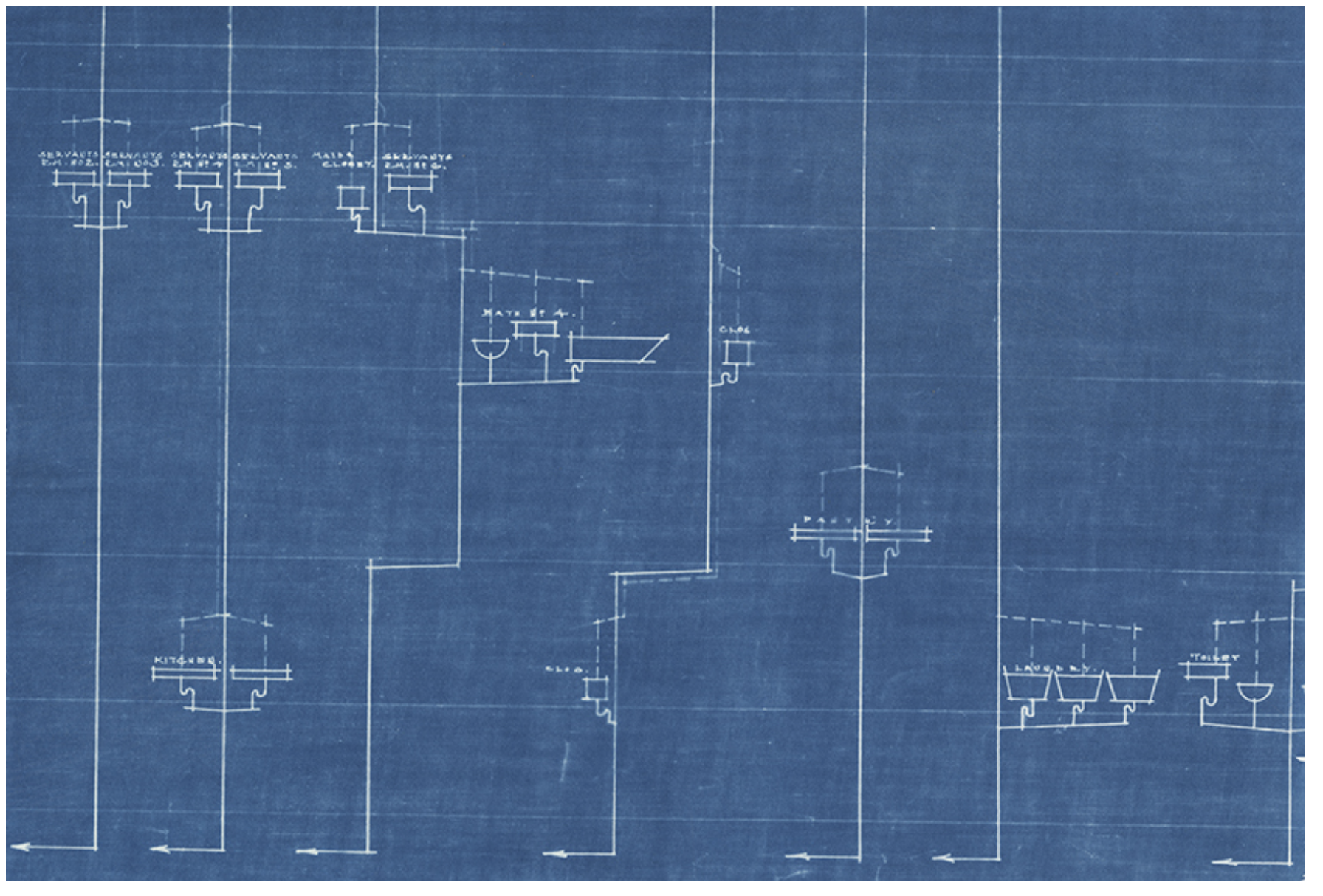

Kioto Aoki: I think a lot of the recent work that I have been doing is site-specific and material-responsive, but also site-responsive. I was looking at the history of the building itself, and so the exhibition is kind of presented in a way that consolidates the history of this home, which includes Eleanor Countiss and her family, as well as the founder of the museum, Dr. Thorek, who was an amateur photographer. So, I kind of merged history and the present space with each other. For example, I had cyanotypes made directly from the old blueprint drawings of the home that I found from 1916.

KA: The work I’ve created takes up all four floors, and is aligned with my interest in paying homage to the space and making work in the space. I think one of the interesting things is that it is hard to tell what is my work and what is already in the collection. I think it’s a way for me to merge with the existing space and collection.

By the time that you get to the third floor, you see more of what you would assume are contemporary artworks, or what’s visually accessible contemporary art pieces, from the two X-ray installations to my series of self-portraits and the portrait in the Japan room. That was just a very funny thing, where I thought I would try to engage with as many spaces in the museum as possible. And me being Japanese, I don’t make work about my cultural identity–at least not with my visual practice. I thought that room was a perfect space to insert my presence subtly.

MHT: Yeah, I really like that. I like the X-ray photographs a lot, too. Did you develop the photos on site?

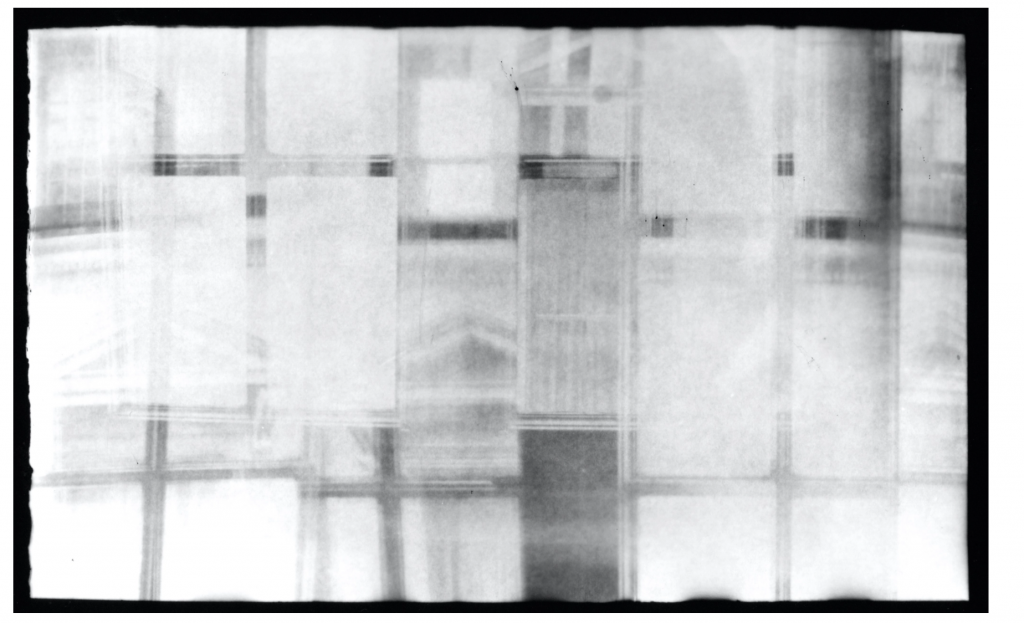

KA: No, everything’s done in my basement. The X-rays visually read as X-rays, but I’m just using X-ray film to make photograms of my hands. I use my body a lot in my work, especially my hands and my feet. I learned that X-ray films are actually double-sided. Cinematic and photographic film have only one-sided emulsion and the other side is a base. But X-rays have double-sided emulsion so you can expose either side, and that’s for the safety of the patient so that the exposure time is lessened while they’re getting the X-ray done. So, I was trying to think about the double-sided nature of that, and to play with the double-sided presentation of X-rays. I’m also thinking of the history of cinema, when there used to be public projections. As a visitor, you could actually choose to sit next to the projector or on the other side of the screen. Back then, there were two spaces where the audience could interact with the image. I’m shooting in a way that engages the space in front of the lens, and I create the self-sufficient and self-reflective cycle of an artist in front of and behind the lens. I do this quite often.

MHT: Yes, it seems there’s so much that you learn from the museum itself and also from the process of creating a photograph, historically and personally, that all merge together here.

KA: Yes, I’m very in for the material process: material as form, and form as material and process. I’m trying to also always engage with the history of analog image-making, so cyanotypes of course were a way to do it. The X-ray, the photograms…they are a very standard, fundamental technique you learn when you first start with photography, and I think these fundamental ideas are an important part of my philosophy as an artist, to always work with light and form and time as elements. I think that the analog process, of course, necessitates that. And we often forget when we are just[working in]Photoshop. We don’t realize that the burn and dodge tool is the exact technique that we’re doing in the dark room. You really have to learn how to manipulate time. You are of course experiencing time as the film develops, and there’s a kind of quietude and space and experience that is lost now with the ubiquity of photographs and the ability to take photographs.

MHT: The same could be said about sounds, since I know you are also a musician?

KA: Yeah, I think so. I’m interested in melodic textures, especially since my instrument is a percussive instrument. I make sure I’m not playing rhythmically or percussively, it’s more about musicality and choreography.

MHT: I’m thinking now about the series of photographs where you kind of disappear. This series contains multiple photographs that are almost the same, a portrait of you, but slowly dissolves and becomes just a white piece of paper that the photo is on. It has a rhythm or a narrative to it…

KA: …a seriality, absolutely. The piece that you are mentioning consists of twelve photos and is really working with the mechanisms of photography and that specific camera. There’s one roll of 120 film that goes inside the camera and you get twelve frames. The exposure time is determined by body time and not by mechanical time, so how long I open the shutter is based on the number of breaths I’m taking. And of course, following the technical aspects of photography, the longer you hold the shutter open, the more light comes in and the image is overexposed . So by the time you get to the twelfth breath, the last image, visually I disappear.

MHT: That’s beautiful. I was just about to ask you about the title which includes the word Breathe, so in terms of breathing with the photographs that really makes sense.

KA: Yeah, the title of the show is Breathe, Fibers of Papers Past, and I’m thinking about fibers as the paper negative process, something that Dr. Max Thorek, who founded the museum, was experimenting a lot with and was writing about. He published two books on photography, and he was a pictorialist. I actually bought the two photo books that he published. He was really into the manipulation of the image and writes extensively about how that can happen through the paper negative process. And with the paper negative you can draw on the emulsion side or on the backside. I am tying in that history of photographic processing that was very prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where paper negatives were extensively used. I often use paper negatives myself, so I thought that would be a perfect way to tie together the two histories and revive them through the fibres of history, whether it’s the stories of the building, of the family, of the home, or of the emergence of the museum. So the exhibition is all about paper and fibers as photographic paper, and the way to engage physically with images, which I think is really important for me.

MHT: Is there any part of the museum that inspired you the most, or that you find yourself returning to a lot during your residency?

KA: I actually really loved the camera that I used on the fourth floor. It was a Henry Clay camera that I found in the collection. I don’t know the story behind it, and the museum doesn’t either, I think, but it was one of these things that was sitting there and no one knew what it was. I understood it to be a camera, so I used it and refurbished it.

The first thing in the collection that I was really interested in was the stereographs, which show medical images made on stereograph cards. They show sectional dissections of the body and are made to be viewed in 3D through a stereoscope, and they’re beautiful. I wanted to highlight that, so I made some stereograph experiments early on.

I was quite happy to see the original blueprint drawings of the museum. There were three iterations of the home. I found that the library and the dining room had been switched at one point. The telephone room and the smoking room were the same place, that’s where the iron lung is now in the museum. I’m very intrigued at the details that still remain in this landmarked home-space. A lot of the ceiling details that I isolated as cyanotypes are still visible. The fountain, which was in the original drawings, is no longer there today, so I put the blueprint of the drawing in the space it would have been in.

MHT: So your photographs are both using what you have found in researching and looking through the archive, but also giving the viewer a chance to see the past and present alongside each other, and in the same space.

KA: I think my practice is really about accentuating the beauty of the everyday and the mundane. I bring attention to those things that we are overlooking all the time, so the fossils on the floor were really important to me, too. They’re in the black-and-white photos I took with a pinhole camera. Those are parts of the home that people don’t see often as visitors, so I wanted to highlight that. All these things respond to the collection, too. I have been working a lot with pinhole cameras, and the camera I made using a matchbox from the Diamond Match Company was an homage to Eleanor’s family–her father and grandfather were CEOs of the Diamond Match Company. They patented the diamond head shape of matches and we still use them to this day. It apparently made them much easier to flare than the rounded-head ones. And that’s the fortune that funded the building of this home. I found a tin on eBay that was from the Diamond Match Company and made it into a pinhole camera and shot details of the home using paper negatives. That really merged the history of the home, how it was built, thE family history, and the paper negative process, which Dr. Max Thorek was writing about.

MHT: That’s so amazing to hear – this object with a history to it, and how you used these even in the process of creating your photographs! Not only do the photos themselves have significance, but the cameras you used and created yourself.

KA: And it accompanies the images of the house that are already on display from the museum’s collection. And those were taken by Eleanor’s son who was dabbling in photography as well. He took photos of his home, and those photographs are exhibited, so they’re supposed to be in dialogue as well with that. It was so lovely to dig into the archives with free reign. I also found many medical glass slides that didn’t make it into the show as well as a lot of other objects that I was able to play around with.

In general, I’m interested in accentuating the moments that already exist in life, so there’s a lot of shooting spaces that have light and shadow, the sort of things that are available to us all. I think we are losing interest in the value of this sort of thing, you know. It takes one to really slow down and take time to really observe and look, and I think that’s the sensibility that we are absolutely losing.

MHT: That’s really true.

KA: You know, with this absolutely digitized world. (laughs)

MHT: Yeah, absolutely! Especially now with how easy it is to take a photo. I took a class one time where we developed film, and to see the photo develop and the slowness of it–it’s really special and tangible, or more special because it’s tangible.

KA: Yeah, I’m so into the physical tangibility of it, but also the process. I don’t shoot whole rolls anymore, because 36 images are a lot! But now on your phone, people just take bursts and edit after, and that’s an entirely different thinking process. You could just take one and have just as good of an image. I think it’s that kind of philosophy of taking time, consideration, looking at things around you, and making that decision and owning it. People think that you can take a hundred pictures and that’s the same thing. And yeah, there’s a time and place for that, and I have a cell phone and I take photos all the time, but I am also spending time in the dark room and making my own slow work.

Breathe, Fibers of Papers Past is on view at the International Museum of Surgical Science from March 12 to June 13, 2021.

Featured image: Anatomy Of by Kioto Aoki. A sectional cyanotypes created from original architectural drawings of the Countiss Mansion from 1916. The image is blue and white. Courtesy of the artist.

Mána Hjörleifsdóttir Taylor is a writer and editor based in Chicago. Her writing has been published in Newcity, Chicago Artist Writers, and Tides Magazine. She is the co-founder and editor of The Documentarian.