In the final minutes of Viral Representation: On AIDS and Art, a day-long conference held at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center that presented research on artistic responses to AIDS as part of the exhibition Art AIDS America, I found the nerve to raise my hand and pose a question to the roundtable that included all twelve speakers who presented or spoke that day.

“Where are the women?”

Tangled up with many other unnecessary words, the question slipped out of my mouth clumsily as words do when they’ve been stuck in my throat for a while. There was a heavy silence that followed as the speakers, only two of which were women, looked at one another to see who would offer a response.

Joshua Chambers-Letson, an assistant professor of performance studies at Northwestern, cut the silence by refining my question—“…women of color.”

Where are the women of color? Or the women? Or the people of color? Or youth? And others largely omitted from these conversations and this research? Where is the information buried? These questions—which have been raised by others such as Kia Labeija and Sur Rodney (Sur)— have been on my mind since I first went to see the show at the Alphawood Foundation’s newly adapted exhibition space in Lincoln Park. These questions seemed like obvious ones. They were the loudest silences in the building during my walkthrough of the exhibition with curator Jonathan Katz back in December. While not completely absent from the exhibition, the low presence of these voices within this art-world context doesn’t quite reflect the scale of the nation-wide impact that AIDS was having (and continues to have) on these communities within the US during the 80s and 90s. If one were to rely solely on what the gallery walls tell us, a viewer might be led to believe that the artistic response to AIDS began as a mostly white American undertaking that revolved around gay men.

That narrative begins to expand once you start to dig into the other parts of the exhibition. The catalog, packed with essays, additional points of reference, and beautiful plates for each work, offers more information for those who are curious, though it only goes so far as to include works from the original exhibition and not the artists who were added to customize the show based on each new location as it traveled starting with a preview version in Los Angeles to full versions in Tacoma, Atlanta, and the Bronx before settling in Chicago. (Chicago’s iteration had the largest addition to the exhibition roster with several relevant local artists incorporated into the checklist.)

Then, Chicago showed up as only this city can through an ambitious lineup of programs presented by Alphawood Foundation, QUEER, ILL + OKAY, and a long list of partners in many corners of the city. The exhibition was pulled further into a present-day context through performances, talks, symposia, screenings, AIDS education events, tours, readings, and sister exhibitions—all of which helped to address the blindspots and blanks left exposed in the voids between works on gallery walls. It was in the programming where women, people of color, the Ls, the Bs, the Ts, the Qs and many others who are obscured from view were given microphones.

Although we are often told to consider programming, publications, and the objects on display all as separate components that together make the whole, the truth is that these parts aren’t circulated and moved forward in history in the same way. Some parts stick while others evaporate or become fragments, remembered in the minds of individuals, photos on a hard drive, a buried Facebook post, or a video in the abyss of Youtube. These events reminded the curator in me of the inherent limitations of static exhibitions and why programming is so important. Then, it reminded the historian in me of how often programming is ephemeral and doesn’t reach as wide an audience as an exhibition does while a catalog, often created leading up to an exhibition, fails to document the important dialogues and art generated once artists, writers, scholars, advocates, and the public encounter it. All parts of an exhibition are not treated equally by history and our collective memory. Chances are the work that comes after Art AIDS America will be built primarily from what was easily commodified—in this case, the catalog and maybe websites and reviews, along with some printed programs and other collateral. But this work is far too important to let its elements slip away.

It took me over three months to write about this because I needed to watch how it all unfolded. Also, for me, the conversation around Art AIDS America being presented in Chicago wasn’t simply about creating press around this opening moment. Nor was it about the giant and generous gesture of the Alphawood Foundation to make space for this exhibition when other major institutions decided not to. More than anything, Art AIDS America provides an historical backdrop to the complexities of these three A’s—art, AIDS, and our country. It is a physical, mental, cultural, and extremely personal site for shaking out the nuances. As silly as it would be to claim that exhibition-making is easy, the truth is that doing the research, collecting the work, developing didactic materials, and mounting it in a space is the easy part of this project when compared to the work that comes next, which is to address the big questions that remain: Why are people of color largely absent from the mainstream understanding of the early impact of AIDS in the United States, and even more so in conversations about the artwork that was made in its immediate wake? With so many people of color, particularly African Americans, affected by HIV and AIDS making up such a small piece of the most widely circulated foundational narratives, what is the curator’s role in derailing those fractured histories? How do we measure due diligence in scholarship and curatorial practice? Then, what conversations need to be had about the privilege and the freedom to fight and struggle in public versus having to pick and choose your battles because deciding between fighting for the survival of a wider community impacted by AIDS and fighting for your own individual survival as someone who is othered within the othered (positive, queer, woman, of color) can all be considered a matter of life and death?

I say this not as a negative critique of Art AIDS America, but more as a critique of the fragmenting nature of exhibition-making, and as a call to those building on this history. I challenge those of us who work to fill in the gaps and pull these stories forward to see this as a point of departure into further and fuller research. I challenge us to find additional ways to capture what happened here, seek out the voices that are missing, and thoughtfully pursue a variety of ways to make this information easily accessible five, ten, or fifty years from now.

I have to say it again. Creating an historic exhibition that is anchored in the early years of AIDS and tracks its cultural and social impact in the US is by no means an easy task. The work presented and uncovered is nothing short of admirable and incredible. But the shaky responses to the question I posed at the Logan Center makes clear that there is still quite a bit of work to be done. And here we are in the final week of the show. It is from this position of looking back while standing at what could be seen as a new starting line that I share my conversation with curator Jonathan Katz that happened in December.

Jonathan David Katz: This is purpose-built. It’s a pop-up. And this is the largest exhibition ever mounted about AIDS. And it was not easy to turn a bank building into a museum-quality space.

Tempestt Hazel: Right. And that shows a real commitment and investment of the Alphawood Foundation, which is pretty incredible.

JDK: Nobody else would build a museum space for an exhibition because it wasn’t being seen in the city.

TH: And it needs to be seen here. There’s a vibrant community of artists, activists in the city whose work speaks directly to this work.

JDK: It was one of my initial concerns that we were able to show it in Tacoma, New York, Los Angeles, Atlanta, but we couldn’t find a venue in the Midwest.

I consider this city home. I was here during graduate school at the University of Chicago and Northwestern—I spent 11 years in this town. And this city has changed remarkably. When I was here, we were battling for anti discrimination measures with the aldermen and having members say things like, “Landlords should be allowed to discriminate against queer people because everybody knows that queer sexual practices involve copious amounts of excrement that befouls the carpeting and drape…”

TH: Wow. So, now you’re returning to Chicago for this exhibition. Can you start from the beginning and give an overview of the show?

JDK: The show is divided into these sections: Body, Spirit, Activism, and the weird outlier, Camouflage. Body is work about the body, Spirit is work about spirituality, religion, or the transcendental. Activism is about politics. But camouflage is where the majority of the work lies. It’s what the show’s about. What I wanted to do was make a show about the fact that the vast majority of art about AIDS doesn’t look like art about AIDS. We only have seen those exhibitions that talk about the AIDS graphic or protest images—the familiar red ribbon or emaciated bodies of AIDS. But what I wanted to do was say, “No, actually AIDS has been a motor for the development of American culture at large. But like so many other things associated with AIDS, we’re repressed that image.”

TH: And with camouflage, I think of the parallels that it has with coded languages like in fashion, for instance. Like flagging and the clever masking that is created by people who align with anything that is sometimes violently or deeply opposed in societies. And the parallels of camouflage when it comes to safety, even thinking militarily.

JDK: One of the things that gets lost is the degree to which it was literally illegal [to speak openly HIV and AIDS in relation to homosexuality]. Jesse Helms in 1987 passed an amendment that made it illegal to reference homosexuality or drug use in the context of HIV. So, art about AIDS was literally illegal. So artists were faced with a stark choice. You could be an activist artist and address art and AIDS, or you could be a street artist. Or, you could make work that camouflaged the politics and spoke out of both sides of its mouth.

TH: Some of these artists are studied and well-known—even if it’s a very basic overview. They’re familiar—like a Felix Gonzalez-Torres or Mapplethorpe. But some of the quieter ones are who I’m interested in. Can you talk about the process of finding those artists?

JDK: We got a Warhol grant that allowed us to travel across the country to look for non-costal figures. Which was central to the conception of the show from the beginning. We also wanted a national exhibition that included a mix of artists that you knew and work that you’d never heard of.

[During our research we found] this work, the literal first work of art about AIDS. At least in 12 years of research it’s the earliest one I found. It dates before any news research about AIDS. It antedates any public mention of AIDS. At first I didn’t believe him—I thought he pushed the date back. I grilled the artist, Izhar Patkin, in several long interviews until I was convinced. But he [told me the story] of when he went to his dermatologist in New York City, and there were four hot guys with copious sarcoma lesions. When he saw that, he said, “Oh shit, something’s coming.” And not only did he go home and make this painting, which is about kaposi sarcoma lesions, but he called it Unveiling of a Modern Chastity.

He got it right then and there.

TH: That story seems like the thing of myths—like when stories are retold.

JDK: That’s the first AIDS film by Lawrence Brose in Buffalo, New York—not an epicenter of AIDS activism. But Lawrence’s partner was English. He was dying. And he went home to die in England. So, Lawrence made a film using images of the two of them together as well as telephone conversations and letters between them to cope with the loss of that distance. This was before the internet when you couldn’t even call.

TH: To go back to the camouflage, there’s the camouflage that you were talking about dealing with how illegal it was to make that work. But then there’s also—and you note this in some of the text around the show—but my curiosity is in the fact that AIDS has never been something that discriminates across lines of race, gender, age, or class. It affected a lot of different people. But I appreciate on the website how you acknowledge and say that there was a lack and challenge of finding–for instance–artists of color to include in the show. Do you feel this show represents them or are they and others still camouflaged within the history of AIDS and the art generated from it?

JDK: The artists of color who make work about AIDS tend to be more contemporary and the weight of this show is on the historical side because that’s what’s unfamiliar to us. In over a decade of research, this wasn’t something that we weren’t aware of. And even as we were sending out a call to experts in the field, we only uncovered two artists that I didn’t know.

I’ve talked to historians of African American art and they explained that it was hard already to be a Black artist, but a Black, gay, AIDS artist? So, it’s not that the show was unrepresentative, it’s that the artists were hard to find—particularly in painting.

In film, it’s a totally different story. We have one of Marlon Riggs’ greatest films upstairs. With film, you can speak to a mass audience, whereas with painting you need one collector to buy the work. And that’s why doing this show was so fraught. I have never been so rejected by so many museums than I was when doing this show. I did the Hide & Seek exhibition at the Smithsonian. I’ve done some of the first queer exhibitions in the country. I thought I’d climbed Mount Everest by doing a queer exhibition at the Smithsonian, but then I found that AIDS is even more politically fraught.

TH: Still.

JDK: Still! And we’re talking about present-day. There were artist foundations who wouldn’t lend to this exhibition because they didn’t want the artist being associated with AIDS to cloud their market position. There were museum that wouldn’t lend work because of it. This is still the damn third rail. It comes all the way back to 1989 and the Robert Mapplethorpe censorship at the Corcoran. No one wants to go back to this—it wasn’t the art world’s finest hour. Everybody cow towed to the winds blowing in Washington [D.C.] and no one resisted it—at least not the museums. So, there’s really this desire not to go back.

TH: It’s surprising but it’s not surprising—I find myself saying that a lot these days.

JDK: Well, as you know, the art world is an extremely conservative world.

TH: But it’s not just one world. There’s the artists working on-the-ground, in the studios, making the work. Then, we envision this other side with the tall towers, galleries, and market.

JDK: Then you have artists like Jenny Holzer who cross that—like with these condom packages she created in 1982. Just read these, “In a dream you found a way to survive and you were full of joy…” It makes me cry every time I read this thing. It’s amazing. “Men don’t protect you anymore… Protect me from what I want…”

We’re asking a great deal of our viewers in this exhibition. What we’re trying to do is address incredibly complicated facts. When you look at Peter Hujars, Ruin Bed, Newark, a series of photos he did of the burned out remains of the race riots from ’67 and ’68 he had just been diagnosed. Why did he go to Newark? He goes to Newark because it became a metaphor for him, of AIDS. Of a community that is being destroyed and no one cares about the ruins that one has to inhabit. Or Robert Maplethorpe’s Tulips in a Glass.

Then there’s Scott Burton, who made these furniture pieces for corporate lobbies and skyscrapers in New York City. If you look at it from the front you don’t see anything, but if you look at it from the side it insinuates gay sex in a way that is so subtle that industry titans sat on these seats without any knowledge of what they were about.

TH: I love that.

JDK: It had to be this way. It was illegal to do anything else. Then, there’s Felix [González-Torres]—perhaps the most important work in the show. He specifies that you cannot avoid walking through the curtain. You have to walk through it. He made this like he made the other curtains, in an attempt to address AIDS elliptically. As the great theorist of resistance [that he was] he said if you attack someone directly to their face, all you do is let them know they’re being attacked. So you have to go around them. This one is called Untitled (water). Metaphors of baptism, cleanliness, uncleanliness, here and there, this world and the other world. All ramifying but nothing explicit. And he said that he wanted to be a virus. He wanted to affect the immune system—meaning the museum.

TH: How has this show been received in the different cities that it’s traveled to?

JDK: In Atlanta the usual neaderthals objected to it and threaten the museum by removing funding. The difference is that in 1989 they would have carried sway, and now people looked at them and said, “That old crap again? You haven’t learned anything?”

TH: And there’s a big queer population in Atlanta. I’m curious about who showed up to the show?

JDK: It was mixed. When the question of race and representation and the exhibition was first raised, it became a way for us as curators to carry that conversation publicly. It’s something we took seriously. The thing that bugs me is that the vast bulk of exhibitions in which questions of race aren’t being raised don’t get attacked. But this one, which is alive to questions of race, does.

TH: Why do you think that is?

JDK: Because it’s the lobster/pot analogy. You always grab the other lobster when you’re trying to escape the boiling water and if you’re outside of the pot, you’re unreachable. I mean, attack the Met, attack the Museum of Modern Art? Attack the mainstream institutions that would never do this show in the first place.

TH: Right. So, where did the show start for you?

JDK: I was approached by the Tacoma Art Museum because they were doing a show and they wanted a theoretical and historical framework. I was clear from the beginning that I didn’t want to do an activist show—because that’s obvious. I wanted to do a show that talked about why Still Here is an AIDS painting.

TH: How did you come across these works?

JDK: A lot of it was research and beginning to really dig [into the work]—work that doesn’t look like an AIDS image. Like this work by Daniel Goldstein—who took the leather covering of the workout booths at the Market Street Gym in San Francisco, a gay gym, in fact, my gym. At a moment when that gym’s membership was dying. He simply framed them—when Gold’s Gym bought the gym, he took them and framed them. They are stained with the sweat of men who are no longer with us. They are incredibly emotional. When I used to work out on them I always wondered when they would change these ratty covers. But then when Daniel framed them I lost it.

There is a huge swath of American culture that has been informed by AIDS, but because it isn’t self-evidently AIDS-like, we haven’t credited AIDS as it’s emotive force.

TH: How did you make decisions about the Chicago artists who are included in the show? I know it extends programmatically, but just focusing on the exhibition…

JDK: We met with a lot of people who have deep roots here. We invited them in and had a conversation. We talked to every group we could think of, including African American church groups. Anywhere we could to find things we didn’t know about. We also really wanted to Chicago show—because of the extraordinary and unprecedented building of a space to house the exhibition—we wanted it to be the spectacular one. And it is. It’s the largest iteration of the exhibition.

TH: What kind of programming has there been or will there be?

JDK: In past iterations there have been talks. This one will have an academic conference for the first time as well as a lecture I’m giving on AIDS in American art and how it’s changed American art. We’re doing HIV testing here, we’re making this the centerpiece of a series of cultural events happening across the city.

TH: This may be a hard question, but I have to ask. Are there any particular pieces that, as you were developing this show, that became the piece that made it clear that you were on to something? I mean, there are many names that we know and works that we know, but some of these artists and works might be unexpected.

JDK: This one. This blew me away. This is Andres Serrano. Serrano did this whole series that looks like orthodox American paintings. Like this one is called Milk/Blood—two main vectors of transmission. It’s politics and art—both on and under the surface.

Or here—Blood and Semen III—looking like an abstract expressionist painting. Beautiful photographs. Or I’m really moved by this piece by Glenn Ligon—My Fear is Your Fear—a piece I didn’t know until I did the research.

Or this—this work by Mark Chester, an erotic photographer, of Robert Chesley who is a playwright who is also his lover. It took place and was made at a moment when gay male sexuality was akin to death and ejaculation was like murder. And the extraordinary bravery of Chesley in baring his HIV infected body and showing himself as an erotic being at a time when gay male sexuality was being policed…and doing it in a superhero costume. Both erotic and vulnerable, victim and hottie—all of it combined. This piece was shown in the Bay Area Reporter in San Francisco. I remember seeing it and thinking, “Finally, someone realized that the ideology of a virus is not a moral judgement.”

TH: So, where were you during this time? Were you able to voice your disappointment in the government, in funding, in institutions as this was going down?

JDK: I’ve been an activist since the moment I came out. I ran the first guerrilla clinic for HIV in Chicago until the police closed us down. We made HIV medications that were unproven, but there wasn’t anything available to free for people. I was diagnosed with HIV in 1982, very early. It turns out I don’t have HIV. For 10 years I was used as a test case for the government because they were trying to figure out why I wasn’t dying. Turns out I had Kaposi Sarcoma—KS—which was seen as an indicator of HIV. Turns out that it’s a separate virus and I was a stressed out graduate student who wasn’t eating well and my immune system was shitty. So I was getting KS lesions though I was not HIV positive. So, I’m one of the few people who had to walk to the pit and then have the great privilege and pain of walking back.

Doing this show meant opening a shoebox in the back of a closet filled with memories that I didn’t want to open. What do you do when you have address books filled with the names of dead people? When you go to funerals every week?

TH: I can’t imagine.

JDK: I remember talking to two friends of mine—one my cousin who passed on. Once in a restaurant in San Francisco, we all thought we were dying of AIDS—all hotties in our twenties. A woman from Nebraska comes up to our table and awkwardly interrupts us and tells us that she couldn’t help but overhear our conversation. She says, “we’re tourists from Nebraska”—and I’m ready to get up and go at it! And she says, “I just want to say, I’ve never heard so much courage in young men before. Godspeed.” And she walked out.

TH: I’m curious about these two pieces—especially this Whitfield Lovell.

JDK: As a Mexican American artist, Rodriguez has a different relationship to death—right—with the day of the dead. These tonguing skeletons is not how I would have painted it. With the Lovell piece, we really wanted a work that talked about the history of oppression and the wire around it. I have had disagreements with my co-curator about its appropriateness in the exhibition, but I lost. [laughs]

TH: In my experience and within these conversations—particularly with members of my family—I find that there’s something generational about people are able to understand how different struggles are related. For me, that makes this Lovell piece’s presence interesting—it’s a little strange—but it speaks to something that is present and relevant. Like how you reference immigrant populations and not solely talking about AIDS in the context of LGBTQ lives and communities, but also acknowledging the fact that it deals with class, race, sexuality—everything.

Did you adapt the show to each location?

JDK: Yes. We felt we needed to make the show alive to it’s different cultural circumstances. And let me show you this work by Frank Moore. He’s one of the great painters who died of AIDS. For him, AIDS was also an environmental degradation. He understood the relationship of AIDS to the body as he understood the impact of humans to our planet. The blood becoming a waterfall, the bed becoming a pond. They’re extraordinary works.

TH: I’m a child of the 80s, so I was just too young to have an understanding of how things were happening and how people were finding ways to survive on an individual and communal level. But I’m curious about a need to create reminders of someone’s ability to be desired and of your sexuality—like in the work of Chesley that you spoke about earlier—and the fact that with or without AIDS, HIV or any illness we continue to be sexual beings. In your experience, was that and is that an internal struggle as well as an external one?

JDK: It was both. The government was closing bath houses. Gay sexuality was being aggressively policed. Giuliani in New York killed gay culture. He closed dark rooms, bath houses, and cruising sites. At the same time, we were individually [struggling]. When I was falsely diagnosed, I made the unusual decision to be public. I was the first openly [positive] person at the University of Chicago. And there was one man who I had a short relationship with. He rang the doorbell and when I opened the door he spat out, “You motherfucker, you killed me.” Then, he walked away. He was dead a month later. I thought I had killed him. It was only afterwards that I realized I didn’t. But I took responsibility. It was a struggle on both sides.

TH: Wow. And what about this piece…feels a little Andy Warhol?

JDK: This is one you may not get if you’re young—and you’re young. [laughs] Yes, it’s in reference to [Warhol’s] Brillo boxes. But it also speaks to a particular controversy. In the early days of AIDS, Trojan wouldn’t make reference to homosexual sex on their condom packages because they were worried that people would see them as gay condoms and not buy them. So, he adds the words “during anal,” which did not exist originally. He added that to give it some umph.

TH: Really?! I never noticed. Have they added it since?

JDK: It was a multi-year battle. Then there’s this piece that’s really telling. If you want to see the impact of race on [the conversations about AIDS], here it is. This is Anne Meredith who takes photographs of women with AIDS—one of the first photographers to take photos of women with AIDS. And what do you see? There it is. White women perfectly happy to be photographed and Black women with their faces effaced. And they did this. Meredith allowed them to efface themselves. Says everything you need to know.

TH: Right. Adding a woman’s point of view for this exhibition is extremely important. There’s forever the need to call attention to everyone being impacted.

JDK: Finally, I just love this room. This encapsulates the exhibition. This piece [by Patte Loper], it looks like a piece of corporate hall art—no offense to the artist—but it’s nothing you would pay particular attention to. But, think about it. You’ve got this deer that’s burst into this pristine interior, through the glass, and is about to cause havoc. It’s a metaphor for HIV. But it’s so removed that you would never read it as such unless it was next to an HIV testing site.

One of my biggest questions about this piece was will people understand what it’s about. And it’s so much more interesting than corporate art.

TH: And there are so many question marks within it that show something’s not quite right. Something about this show that I really appreciate is that even though it’s taking a deeply historical approach, it doesn’t feel overly dated. What I mean by that is with how this work is discussed or taught—at least art historically—it’s often presented as a moment as if the world moved on from that moment in time. So the work that tends to represent the conversation is often rooted in that period of time. So, I applaud the ability for this exhibition to break it outside of that—to create a show that is a testament to the realities of it over time. That AIDS is not just a moment, and it goes far beyond when it was new and at an early point of shock—when people were reacting, didn’t know what was going on, losing family and loved ones…

JDK: …when the eagle was really extreme. As I was curating this show my ex died of AIDS. It really drove home the point because when I talked to people about Kurt’s passing, people would respond by saying, “People still die of aids?” Yes, people still die of AIDS.

TH: So, it’s a continued struggle. It’s something that is still being addressed, which to me makes this exhibition feel like a benchmark moment in a forever-exhibition. Do you see this continuing in different ways? What is next? How does it continue to build?

JDK: Look, I think it’s a damn shame that the first major exhibition dedicated to AIDS is taking place in 2016/2017. Thirty five years after [it started]. I think it’s happening after because, frankly, only with new pharmacology is AIDS capable of historical distance. When it was raging among us we would have never been able to do this show. I want to find that knife-edge point between an historical exhibition of real contemporary relevance. I’m gratified to hear you say that it doesn’t feel dated because that’s exactly what I was going for. I don’t want this to be fossilized. This isn’t about things that are gone. AIDS is still there. And the work still has the capacity to move and to shock, and to laugh, and to hurt.

TH: So, for the younger artists doing this work, calling attention to these questions and topics, or curators and scholars—is there anything you would say to them from the perspective of someone who has built a career doing this? Or is there a place where you hope they will continue to build?

JDK: That’s why I’m a professor—I’m trying to train the next generation. I think the key element of being a pissed off queen like me is perseverance because they will say no. And it’s imperative not to [let that stop you].

Art AIDS America is on view at the Alphawood Foundation through April 2, 2017. Learn more about the exhibition, catalog, and related programs here.

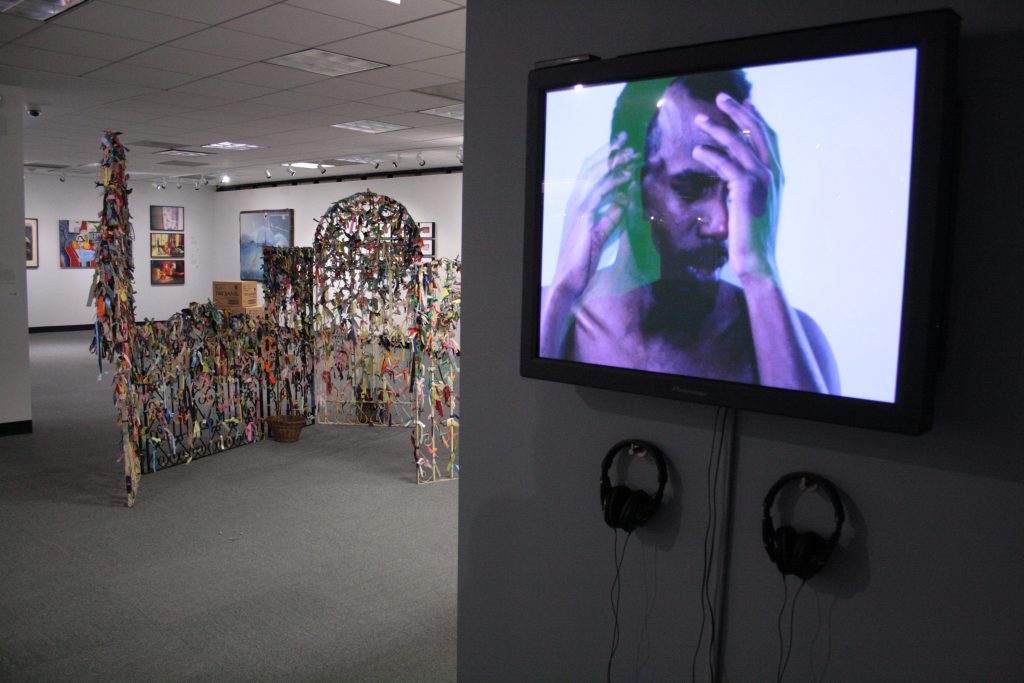

Featured Image: Installation view of Art AIDS America. Photo by Sixty Inches From Center.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center and the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including an upcoming book by Cecil McDonald, Jr. published by Candor Arts. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. (Photo by Zakkiyyah Najeebah.)

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center and the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including an upcoming book by Cecil McDonald, Jr. published by Candor Arts. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. (Photo by Zakkiyyah Najeebah.)