Metal breasts dotted the walls, intertwined with mushrooms and cat tails; and a feminine body, cast in bronze and shining wood, levitated midway up on the space’s white walls. For purposes that will become evident later, let’s call this piece a girl, with full recognition of that word’s expansive and suffocating possibilities.

In Shana Hoehn’s Basket Toss, up at Prairie Projects for the month of April, viewers were asked not only to accept the responsibilities of this complicated closeness—to become voyeur and force majeure upon the seemingly passive girl—but to understand the reciprocity of such positioning. That when you look at someone, when you enact change upon them, they too change you in return.

“Basket toss” itself is a reference to a cheerleading stunt where two performers throw a third into the air; their body either stiff or moving through a series of fantastic contortions. The athlete who freezes flying through the air, just like Hoehn’s girl on the gallery wall (the piece itself also titled Basket Toss) brings to mind slumber party games and magic shows. However, all are efforts that seem to speak to a larger, more unwieldy, excessive act of wanting; especially on the part of the flier and the floater. Why would someone ask to be taken by the air?

In Greek mythology, the stories of Daphne and Apollo, and then Medusa and Poseidon, are studies in evasion: they detail the consequences of capture, they’re what happens when your body changes from sovereign territory into something new. Considered by writer Lauren Guilford in the show’s written materials, the story of Daphne and Apollo begins as a story of pursuit. Apollo, hit by Cupid’s arrow, spies Daphne (a river nymph), who becomes the desire to end all others. Not even the gods are immune to Eros. Apollo ardently pursues the nymph, but she remains out of reach. Yet the day comes where confrontation, collision, appears inevitable, for not even nymphs can run forever. Daphne’s body changes. Her heartbeat slows, her breath stops, the sinews of her legs affix to the ground, bones splinter under glossy bark, and green leaves burst from her blood vessels. Daphne is now the sacred laurel tree, the unknown girl-nymph rendered semi-legible through the sun god’s overwhelming desire. Domination is semiotic in this story. Daphne was once unknown, hidden in the woods until someone tried to give her a new beginning and end.

Like Daphne, Medusa’s story is built upon ambiguity, the power of the unknown, of circling desire, of touching and being changed through it. The fates, the characters, the wants, the needs, the sorrows of both figures, float and shift, and depend upon who tells their stories. We don’t know if Medusa was a monster, or if her extraordinary beauty rendered her monstrous in the way beauty always seems to bring violence upon its bearer. Did she come to Poseidon by choice? Did she break her vows of celibacy as a priestess of Athena by choice? Was it love, was it force, or an undefined in between? Did she wake up alone, incense smoke staining the temple walls and slow shimmery hisses echoing in her head? Did each glance, each heart now cleaved to stone, hurt: the pain an intimate reminder that violence was also hers to share? Medusa met her end at the hands of Perseus, a hero in Greek myth, who is said to have tricked her into looking at herself, but maybe, just maybe, she wanted to finally see. Stone here can cool and comfort, mend and not break. There’s a way then to see both tales as ones of transformation, of flight and freedom, of changing and being changed. A tree, a monster, the beloved, the lover, the dead, the living, and all that floats in between.

When I was a child, I played the same game every Sunday during Mass. I’d ask my mother if I could use the washroom and, once outside the chapel, I’d head straight to the baptismal font. I’d climb up the ridge of the fountain, its four foot high base appearing like Everest, and begin a precarious, wobbling walk to its northernmost point. The priest’s voice, speaking of angels and demons, the vulnerability and porousness of the human soul, echoed as I would then jump to the nearest chair. As a child, seconds feel like hours, time moves like magma, and you’re flying, held only by air. It was a game that allowed me a certain thrill, I could leave my body but the ground waited tantalizingly below. I always enjoyed the possibility of falling, it reminded me of my own beginning and end, the demarcations between me and the other.

When I was seventeen, I woke one night aloft, briefly suspended, as my bed rattled and picture frames shook on the walls. (Growing up in Saint Louis just north of the New Madrid fault line, we were at risk to rumblings from tectonic plate shifts, though they rarely occurred.) Due to the relative rarity of earthquakes, my portion of the Midwest firmly centered in the colloquially known Tornado Alley, I thought instead of the anecdote I had recently learned: the supposed case of demonic possession that inspired the film “The Exorcist” had taken place in Saint Louis. Much of the case is now conjecture as the child who survived the grueling months-long ritual is still alive and living in relative anonymity. What we do know is that for three months a fourteen-year-old boy lived under supervision of priests. Every night he was forcibly strapped to his bed. According to priests’ reports, the child was strong enough to one night escape his bindings and pull a bed spring from his mattress to stab a priest. The stabbing resulted in an injury that required upwards of one hundred stitches.

He was said to be possessed by the spirit of a deceased aunt, a state of being which caused his “body [to] distort and transform” his “heels touching the back of his head, his body forming a loop.” The body bent, no longer linear, appears different than the ramrod straight lines of Hoehn’s girl but the boy’s excessiveness—the too much-ness of his strength, his pain, his determination, his intimate connection to a feminine sign—expands and complicates what it means to be an agent of the dominant discourse. His was a body marked as other, whether through illness or grief for an absent beloved aunt or teenage ennui or something else entirely, he too could fly.

The feminine, the femme, the female, have long thought to be susceptible to spiritual possession. This relationship ties to a pathology of the feminized body, those marked by excess and deemed unknown under the dominant discourse. There are countless films where possession (think: the “Conjuring” franchise, “The Devil Inside,” “The Exorcism of Emily Rose,” “Paranormal Activity,” or “The Exorcist”) is fought, sometimes to the death. These are stories that assert loudly the inviolability of one’s soul, the sanctity of one’s spirit; they trumpet to fight and die for possession of oneself is a worthy cause.

In a sleep-induced haze that same night, I remember thinking spirits, if they existed, were welcome to me. I was curious to see what might happen next. The next morning I was puzzled by my response to what was an out-of-the-ordinary occurrence. As a child who regularly attended Catholic mass and was endlessly intrigued by the idea of the supernatural, I thought my reaction when confronted with the unknown would be, well, different. My own easy acquiescence, my own desire to see, puzzled me at best.

The classic scene of possession always seems to happen in a bedroom. The detritus of childhood lines the walls, the sheets are usually white, and the body of someone innocent of the world, yet part of it, begins to slowly rise into the air. Those white sheets begin to slip off their owner to expose a bare calf, a sliver of arm hanging akimbo, as the possessed never seems to wake from their state of arched suspension. The physicality of the possessed might look different than the total control of the levitator, but belongs to the same family; they all exist on the same spectrum of power and control: who has them, who wants them, who sees them, who takes them, and what happens after the taking occurs.

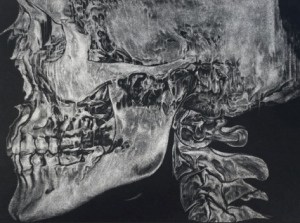

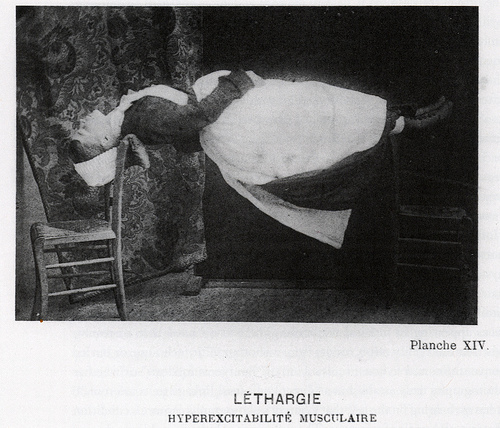

A headless figure contorted into a backbend resembling an arch, Louise Bourgeois’s hanging bronze sculpture, the Arch of Hysteria (1993) is often read as female. The sculpture’s pose itself has a long history in early medical studies of hysteria at Salpêtrière, a women’s hospital in Paris during the late nineteenth century. Hysteria was inscribed upon the bodies of female patients through the photographic studies of Jean-Martin Charcot, an early mentor of Sigmund Freud. The women housed at Salpêtrière were those marked by society as too poor, too ill, too disabled, too pregnant, too queer, too old, simply too much. Charcot’s photographs feature a select group of patients repeating a particular contortion or gesture that Charcot diagnosed as their symptom, the particular hat trick that revealed the origins of their hysteria. In one of these photographs, titled Léthargie Hyperexcitabilité Musculaire (circa 1876-78), a woman in a maid’s uniform lies extended between two chairs, her head balanced on one, her feet on the other; an echo of Hoehn’s flying girl.

In early twentieth France, live-in maids Christine and Léa Papin murdered their employer and her daughter (the murders forming the basis of Jean Genet’s 1947 play The Maids). The sisters are considered an infamous case of folie à deux, “the madness of two.” The structure of folie à deux depends on partnership; in order for feelings, delusions, dreams, emotions, to take shape within the world, there has to be a witness: the person who awaits the flier’s landing, or a spirit’s host, their arms spread wide, their body open. Transmission needs to occur. The lover needs a beloved. Again, again, again.

Charcot’s photographs are built upon such repetition and transmission. He categorized and classified the supposed systems of hysteria by documenting the women’s poses. Yet, their bodies tell many stories, some much older and deeper than those Charcot sought to capture in his operating theaters: think of these stories as kin to actors who bring some of themself to the screen, the stage. Those people who tear out pieces of their heart for us, the audience, to ponder in wonder.

Think of Isabelle Adjani’s hospitalization for her breakdown after filming Zulawski’s 1981 “Possession.” On the surface, Adjani’s character is a woman who betrays her family for a monstrous squid-like creature she fucks in squalor. On the surface, Léthargie Hyperexcitabilité Musculaire is a photo of a patient, a woman who is seen as ill; a person cordoned off from society. Yet questions always creep in, the unknown just like the tides. In “Possession,” Adjani’s husband neither trusts nor understands her. Her sexuality was already under scrutiny. Why was she sad? Adjani’s desire to leave her husband and son constituted something monstrous in her husband’s eyes; it was desire in excess, beyond his understanding. She was a monster before the squid lover ever appeared, just like the subject of Hyperexcitabilité, who was never quite the right kind of woman in the eyes of society. Much has been written about these photographs, that they encapsulate both Charcot’s domination and female resistance, but I don’t think the stories of power are ever that simple or clear cut. Within the walls of the Salpêtrière the patient deemed ill, the body under examination, was rendered into something grander and more mythic than society ever allowed. Flight can happen even within the most confined of places.

Within a psychoanalytic framework, hysteria is not reduced to anatomy. Rather, hysteria occurs when words fail and language proves insufficient for the task at hand. When faced with this, your body does its best to tell the story. Your story is given meaning, you see it reflected and refracted in reality’s icy light. Some things need a reason, though most often they do not possess what is needed. It’s like how wind sings as you fall, the metal of bed springs and operating gurneys both burn, the cold stone of the temple floor is a comfort after the god leaves you bleeding, and the reassurance of flesh now joined forever to the solidity of the laurel tree. Or how you can fly even when your body is held tightly in place, only bruises left to remind you of the fall. This is not the end. Rather, the story begins when you feel the ground, flutter your eyes open, see your snakes, feel the moon on your leaves for the first time.

Maybe that’s what I hope to leave you with, both comfort and warning. Hoehn’s levitating girl vibrates with life. The girl is not alone because you’re with her, you change one another.

About the Author: Annette LePique’s writing has appeared in ArtReview, Chicago Artist Writers, Chicago Reader, Eaten Magazine, New Art Examiner, NewCity, Stillpoint Magazine, and many other publications. She received master’s degrees from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the University of Chicago and is a 2023 recipient of the Rabkin Prize for art journalism.