Featured Image: The exterior of Hyde Park Arts Center at night. Eight colorful portraits are projected onto HPAC. To the far left of the portraits is a dark square with the text: “What Time Is It? A Cultural & Civic Archive.” Below the projected portraits are metal doors covered in red, blue, yellow, and black spray painted art. Photo courtesy of the artist.

INTRODUCTION

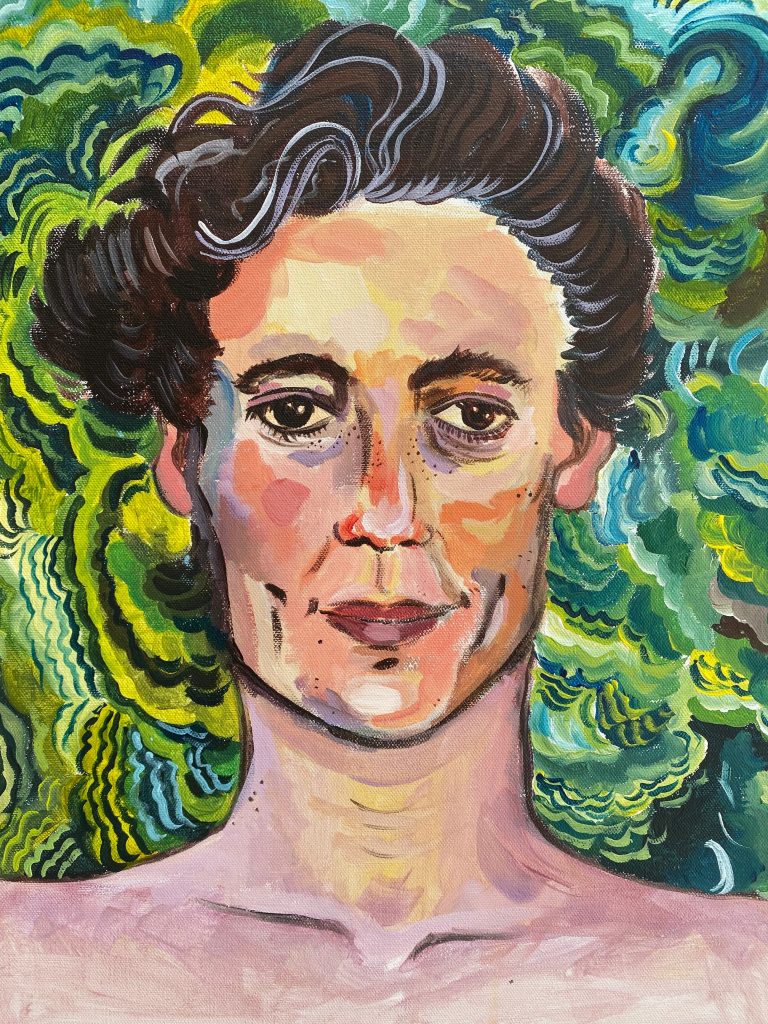

Irina Zadov’s portrait series and accompanying conversations, What Time Is It? began only a couple of months after quarantine. It is a long process of asking Grace Lee-Boggs’ question: What time is it on the clock of the world? It is both a philosophical and practical enquiry.

Beginning on May 4th, 2020 with a self-portrait, the series has expanded past its original scope to include an ongoing podcast holding conversations with artists, activists, and educators; an exhibition at the Hyde Park Art Center in April of 2021; and artistic interventions over the summer of 2021 in collaboration with Honey Pot Performance and the city of Chicago’s We Will Chicago.

The following dialogues have been edited and rearranged with intent towards clarity, brevity, and to thematically tie together three separate conversations taking place over two weeks in April 2021: one with Zadov alone; another with collaborators Najee-Zaid Searcy and Rivka Yeker; and a final one with Zadov and portrait partners, Tonika Johnson, Fawn Pochel, and David Stovall. To find the full, unedited audio transcriptions click below.

PART 1: PORTRAITS

Persephone Van Ort: So, would you be down to describe the project in your own words?

Irina Zadov: Yes, so, the What Time Is It? Portrait project is… Sorry, I literally have the mission memorized ‘cause we’ve been recording this podcast so I’ll try not to tell you that (laughs)

like:

(makes voice)

“This is a civic and cultural archive rooted in…deep listening! Relationship building! And radical imagination!”

Ok, I’ll say it in my own words: It’s a… basically, when the pandemic started I felt lonely and I missed people. I was doing a yoga session with our mutual friend Peregrine, and I was in a meditation and this idea came to me of how can I reach out and connect to people that I miss. And the Grace Lee Boggs’ quote is one that, over time, has randomly popped in my head and now felt like a good moment to dive deep into it, and I was very curious as to how people are perceiving this moment. And of course that changes all the time. My intention behind the project is to connect and listen and try to archive in a way that’s maybe a little bit different from social media and the news cycle that invites listening and relationship building.

PVO: I really enjoy reading the interviews and finding the vast array of [answers]: “this means just chilling out, or hanging out, or doing whatever you need to rest.” David Stovall’s answer really stuck out to me. It was, “To destroy me is to invite your own catastrophe” or something along those lines. Were there any responses from others that really hold a firm grip on your hand?

IZ: I just want to clarify they are not interviews, they are conversations. A lot of people say that and I have to correct myself too, just because I am not a journalist and I don’t go in with questions. I paint people and they talk. I don’t ask them anything at all except for that one question: “What time is it on the clock in the world?” I usually save that ‘til the very end so a lot of [the conversation’] is very meandering and people just talk about anything and sometimes they are like, ‘Oh that’s just like therapy, thank you.’

Ok, so anyways, to answer your question, if any of this stuck out, I think the very first portrait I painted, after myself, was Zakkiyyah, and we had a conversation about who gets to… like, who is an authority on time, essentially.

“On who’s clock” and that something that has stayed with me a lot because we all operate in this world of deadlines, and schedules, and calendars… Who gets to set the clock and how do we understand time? I think a lot of people spoke about time folding onto itself or different moments in time coming together, so that concept of… who’s controlling our understanding of time and how do we take ownership of it, is something that really resonated for me.

PVO: Who, at this point, is your ideal audience? Is it the people that you’re painting or somebody else?

IZ: I really see the value of this project in the future as a time capsule, as something that people can look back on. I just read a book of oral histories from Chernobyl, and, you know, I grew up right next to that area, so obviously I knew what happened, I knew the basics of it, but reading these oral histories brought it alive for me in such a profound way. The whole narrative is basically about the ways in which our governments lie to us. It’s obviously an interesting time to be reading that, and really made me think of the value of this kind of archival work, because of course we have all the tweets, and articles, and social media posts, and at the moment it is overwhelming… but looking back I do think there is value to that slow meandering storytelling, and to see what were people actually thinking and feeling at a time when there’s so much upheaval… and uncertainty.

PVO: You mentioned in your first entry that this was a decision to re-explore portraiture after a time away, and I’m wondering how your relationship to painting has changed during this time. With this process specifically.

IZ: I had a very specific kind of art education as a young person and when I was in high school I did paint portraits a lot. I would sit down with folks and I think because I’m an anxious person, painting someone would give my hands something to do and then we’d have this conversation where otherwise maybe I would feel less confident. Then I became politicized and started to really question visual arts and my role as a cis-white person painting things and people. I started moving away from my own artmaking and I moved more to curatorial practices and education and facilitation and admin, and I really haven’t painted consistently in like twenty years in a serious way, so getting back into it now…

I still have a lot of questions about portraiture and the white gaze, you know. I think that there’s parts of this process that are still complicated for me and unresolved. When I paint people I like to ask them to participate in the process so I ask, like, how they would want to be depicted. I really try to be collaborative and as consensual as possible, but obviously it is my interpretation that guides what the final product is.

It’s… It’s still complicated, you know, I don’t have a final resolution. I guess that something I will say is I’m really interested in this project evolving beyond something that is filtered through me. I’m really interested in working with young people, and have lots of different people creating portraits and conducting conversations, so it’s not that I’m kind of an omnipotent viewer or vessel. I think just by ways of the pandemic, and being at home, and having the skill set, I wanted to practice, but now that we’re beginning to open up a little bit, I’m really interested in involving more folks.

PART 2: PROCESS

Persephone Van Ort: Would you two introduce yourselves, state your name, pronouns and just what your role in this project is?

Rivka Yeker: (chuckles) Najee, you wanna go first or you wanna go first?

Najee-Zaid Searcy: I will support you on that. My name is Najee-Zaid Searcy. I use any and all pronouns. I was born in Chicago but I grew up in Dekalb, IL, and moved back in 2010. Since then have done a loooot of different art, and more recently [I am] deeply exploring digital media and how we can incorporate community in our processes when thinking about arts and culture work in larger structural shifts in the world today.

My focus in the project has been in the digital media sphere, thinking through podcasting edits, working alongside the full team to help to produce the podcast component of the work, thinking through intellectual property rights, how we can (clears throat) rightfully and justly incorporate the amazing talent that it is here in Chicago into this civic and cultural archive while providing ownership, while being in conversation with ongoing works of said community members….and also just as a cheerleader!

I really love the work that Irina, Rivka, and Jay [Sath, a graphic designer] are doing, and especially all fifty folks or however many folks we land on, that are receiving a portrait, and an interview. These are very, very strategically selected people because they are so vital to the fabric of the arts and culture of Chicago and how we approach civic engagement and do community work. But yeah, I’m gonna pass it over to Rivka. I hope I have bought you enough time.

RY: (laughs) That was perfect. Do I even have to say anything? But–

Hi! I’m Rivka. I am from the Northwest suburbs but my family is also from the Soviet Union and I grew up in, sort of, the whole Rogers Park to Northwest suburbs and migrated to Chicago, and I basically started as a transcriber, turned into a creative consultant, and also a cheerleader.

Same with Irina and Najee, my belief in the world is that culture should be at the center of all political movements. The way we understand one another, the way we learn about history is, I think, best through ethnography, through storytelling, obviously through interviews, conversations–exactly what this project is, it’s a civic and cultural archive. This is what people should be listening to in the future, ten years from now, if they want to learn what was going on with Covid, Black Lives Matter, uprisings, or any type of social justice, these are the facts, this is what is actually happening. My role is just making sure this is getting across and we make it into the project it’s meant to be.

These people that are getting their portraits done are sooo compelling and interesting and [are] artists themselves. This project has reminded me that people are doing the work and what we are set out to do is to highlight that hard work and remind people to continue being hopeful because shit… shit is happening, so that’s my spiel.

PVO: You talk a lot about cultural archives, and I was wondering how you hope to expand around and possibly past Irina’s initial purview of this into being into what can be.

RY: This is education for a lifetime, and the beauty of this is that all of us see it so clearly which makes it actually kind of easy, because what we are finding out as we go is that we are on the same wavelength and any time someone brings up something like, “What if we did this? Or included this? Or tried this?” We’re like, “Yeah! That sounds great!”

NZS: Percy, would you mind repeating the question again?

PVO: Yeah, of course. How do you hope to expand on Irina’s initial work or past it?

NZS: How do I look to expand on Irina’s initial work and past it?

PVO: Yeah.

NZS: Please hold.

She literally lives for the archive, it’s not even a joke. Irina so captures the importance of critical moments and critical mass like, “Hey! We are in a global shift in global history, global Herstory and Ourstory!” These are the moments that people reference when they build their curriculum, when they talk about world history, when they build policies, make structural change. [Irina’s] original work as I saw it was really elevating those that have a strong legacy to necessary change in the city of Chicago, especially when it comes to transformative and restorative justice, activism, civic engagement, youth work, intergenerational healing. There’s a lot of different skill sets, identities, wisdoms that need to come to the center of our city in the way that we think about our present, analyze our past, and build our future, and so it then moves beyond her and becomes that emergent process of responding and building from a place of care that incorporates what we’ve learned.

If we are good at listening, the benefit and beauty of podcasts is that we literally listen to these conversations for hours, and hours, and hours. And we are transcribing and editing and communicating and ingraining, etching so much of the lived wisdom and experience of each of our community members that are reflected in this work, and the folks that they wanna bring into the archive, and the nature and the other ancestries, indigeneities that they wanna bring into the archive. So it becomes, I believe, in a future iteration malignant, it becomes a type of mycelia, a type of network that, in days past, would operate outside the visibility of a larger system such as our city government, larger agencies, or larger organizations.

I think that if we are doing good to Irina’s initial plans for this project, it would help strengthen ties and relationships and connections that are essential for us to radicalize our environment to be one of care, to be one of justice, to be one of equity. To constantly be a moral compass to our city and to really shift our municipal focus and our cultural lenses to the reality versus a projection of a fiscal budget… you know, whatever other white supremacist capitalist frameworks you insert here.

Replacing that space with something valuable and meaningful for the people who live here and who are affected by the city of Chicago.

RY: [At the beginning] there were some conversations that were just pandemic talk, Covid; I mean there was obviously talk of systemic inequality, but when June hit and the uprising started, the conversation shifted obviously. What’s most fascinating about this project is that these conversations were happening in real time in reaction to historic moments and Irina was capturing it. That’s what made all of us realize, “Oh! This needs to be preserved in a way that’s much larger than just a website.” It needs to be preserved through audio, it needs to be preserved in a mural.

And the people that Irina was talking to were not just policy makers, or government officials; it was people that are working on the inside, are artists themselves, are community organizers, culture organizers, have been in the inside [of government and institutions] and have been on the top of the inside, and left the inside because they were hurt by the inside.

One of the people is Aislinn Pulley from Black Lives Matter Chicago. Aislinn, I think, was in the news talking. Always on the news, right? But getting this conversation with Aislinn in this way… because Irina has said: “I’m not a journalist. I’m having a conversation over tea with my friend, and they are telling me the inside scoop.” Aislinn is not in front of a camera for NBC news or whatever, saying these things they have to say in order for people to listen; they are saying their heart and their souls and their truth to their friend. And that’s a conversation you can’t access on public news.

PART 3: PEOPLE

Persephone Van Ort: If you all can go around, say your names, pronouns and associations or roles that you occupy?

Tonika Lewis-Johnson: Hiii, I’m Tonika Lewis-Johnson, I’m.. the term I’m using these days, it changes like every month or so, is social justice artist. My primary medium–I can’t even say photography anymore–anyway: social justice artist who lives and centers my work on greater Englewood.I am the creator of a project called Folded Map as well as one of the co-founders of Residents Association of Greater Englewood, and most recently Englewood Arts Collective.

Fawn Pochel: I’m Fawn Pochel. I am Saulteau, I am the auntie of the Chi Nations Youth Council. I have been doing community work within the Chicago Native community for about the past thirteen years now. My pronouns are she or they.

David Stovall: Dave Stovall. I actually like the pronoun “y’all.” I guess it’s the Chicagoan in me. I am a professor of Black Studies and Criminology, Law & Justice at the University of Illinois Chicago. I’ve been working with young folks and families around education and housing for the last thirty years.

PVO: Dave and Fawn, you two had your interviews with Irina back in the springtime, just after the pandemic started and I think just before the George Floyd protests began. I’m kind of wondering how your answer has changed to the original question of “What time is it on the clock of the world?” Or has it at all?

FP: Yes. I think, yes, it should be an answer for everyone. I’m not gonna lie. After the interview, just seeing the racial tensions grow across the nation, specially focusing on the anti-Blackness within, not only the Chicago Native community here, but Native communities across all of the so-called Americas, has been very visible and it’s something that I, light-skinned Native woman, have had the privilege of ignoring for such a long time. But I work with young people, I work with Afro-Indigenous young people in particular, so they check my ass real quick. Since then I’ve been trying to do the work to push forward more–for a lack of better terms, I hate this–anti-racist, anti-bias work.

Having these conversations with…anti-Blackness within the Native community is something that we’re not doing, and is something that I only see our young people doing, and when it’s our young Afro-Indigenous people, it upsets me because this emotional labor should not solely be put on them.

DS: I was thinking about it this morning. It’s one thing to understand what it means to be Black in a space founded on white supremacy, slavery, genocide, and wrongful land appropriation. It’s another thing to be reminded of what it means in its most visceral form. […] I’m born and raised in Chicago, I’m almost fifty years old, so I’ve come to grips with what it means to be Black in the world that hates you. But you are reminded in this visceral way, and it makes you understand it differently, right? The scholar Saidiyaa Hartman always says something that sticks in my head. She says, “Look, we have to come to grips to know that the Black body has been rationalized as the gratuitous site of punishment, right? It’s been normalized to that.”

We’ve been here for a long time–this thing around ideas of the world’s reckoning–but then Black folks saying “we’ve been for a long time.” So now, because we’ve been here for a long time, what’s the next set of work going forward?

TLJ: I feel the same way. The terms white supremacy, systemic racism, and all of the ways in which we describe injustices are now more common in the public. It’s spoken about on national media. I think that is a necessary step in the direction that obviously we need to go in, but [a national conversation] takes so long to get to. I definitely feel we are in a reckoning with public consciousness around this issue in a way that hasn’t happened in a long time, and in a new way with new generations and different kinds of solidarity. As much work as we still have to do, I definitely notice very strong localized movements of solidarity, and the attempts across different races to kind of solidify this coming together, recognizing how people of color in, as Fawn said, so-called Americas, have been mistreated, brutalized, here, in the same ways. I think we’re all starting to raise our consciousness to attempt to learn the intersections of injustices that we’ve all experienced at the hands of white supremacy. And I think that’s very, very important for the public to learn about and to know.

PVO: What would y’all hope is held onto from this quarantine period? Anything that can help us move forward and move into something else?

DS: It’s gonna sound hella basic. One of the things that make me hold onto hope is the ability to imagine a time where we are back in community with each other outside of the digital space, literally just being able to see [people] in [person] like “Man! Tonika, what’s good? it’s good to see you, fam! It’s been a minute!” Right? Just be in folks faces. That type of interaction holds, for me, the essence of hope. The understanding that we will be in community with each other, and it’s not about holding on, as much as it is about building for the day where we will be in community with each other.

FP: Part of what all of this has brought for me is seeing people really want to learn and engage about the land they are occupying.

[…]

Working at the First Nations Garden over this past year, community has came out and built over fifty-two boxes for us to plant food and medicine for this upcoming growing season, and that space was used to organize the Black Indigenous Solidarity Rally that happened on July 17th [2020] downtown, which ultimately got the Columbus statues removed. Seeing youth–especially our Black and Brown Indigenous youth–utilize outdoor meeting space to understand their privilege of being young and able-bodied, but also understand that they are the ones that push us forward.

[David] Stovall bought up the Coil Mound; there hasn’t been a mound built by Indigenous people since the founding of the United States up until November of 2019. The Chicago Native Community–led by artist Santiago X–built the first mound in Schiller Woods, a site that has remnants of Mississippi and Erie, so seeing people come and support indigenous earthworks, want to engage and not just outdoors, but understand that this landscape here in Chicago is and always has been Indigenous […] It has been something beautiful for me to experience.

TLJ: It’s literally the same kind of process of injustice that Indigenous people have experienced, that Black people have experienced, and Asian-Americans […] it’s the same pattern of (laughs) injustice. Injustice is not even a good enough word. Atrocities! So you know, I just feel me talking about the Black community has to also include and align itself with what other groups of color have went through, but also uplifting the very specific anti-Black history that this country has done. I just want the spirit of community, and empathy, and the passion to help move the needle forward and correct all of this. The redress. All of it. That’s what I hope continues to move forward.

PVO: Do y’all have any hopes or plans of how to archive this time? I’m wondering if you know of any work contributing to that?

TLJ: Yes, and especially so many photographers that I know. There was so much documentation from other photographers that I know that I was, “You all got this! I don’t need to get out there. I’ll just focus on my other photography projects, cause you all got this!”

The one that stands out, his name is Vashon, young Black male photographer.

DS: Yeah! His book! That book is fresh!

TLJ: I’m really glad that people have found amazing ways to document this period, because I’m always interested in future histories, and how it’s going to be spoken about. That is my training as a photojournalist, as a journalist, and artistically speaking my appreciation for the ways in which we memorialize or talk about history, this is a moment [where] we have so much content, that it will make no sense if this is spoken about incorrectly.

DS: A good friend of mine was talking about the past, future, [and] present in terms of how the connections to the past propel us to a future. And this whole moment made me think about Frantz Fanon. In the late fifties he wrote these things, he said, “Each generation out of relative obscurity will fulfill their destiny, or betray it.” Right? For me, this moment is seeing young people, seeing folks who are coming to some type of awakening, fulfilling their destiny.

And this question around moments to movements: people would look at me like I had eight heads four years ago when I would say something like, “White supremacy is more than white supremacist nationalist terror, that we gotta think about in terms of ideology, we gotta think about it in terms of material reality, and we have to think about how white supremacy lives in us,” and just that being into the lexicon, right? Or even people starting to think about the word “abolition” in terms of the ways in which folks understand it, and bringing back what critical resistance and folks in the 1830s were talking about in terms of abolition, and revisiting that. So I think about the past, future, present in terms of all these things that are now bringing us back to understand that there have been moments when people have been talking about this.

And I really like the series that Colin Kaepernick did for a part of a digital magazine called Level, and one of the parts of Level was dedicated to abolition. They talked about folks who have returned home from incarceration and talked to folks who are currently incarcerated. It was a really interesting, wide, broad piece of digital media that I think is an excellent documentation of the moment, but also pushing us to now think about all these things and where the contradictions occur. And where we fall short. But at the same time I really like what I’ve been seeing in this last, say, a year and a half.

FP: I don’t know how to follow those answers…

(all laugh)

I’ve been enjoying the memes. They are truthful, they’re honest, they’re funny as fuck… Can’t wait to teach about that in History Class ten years from now.

(Dave laughs)

There’s academic seminars about what landback means and it’s a meme.

(laughs)

It will always be a meme.

TLJ: You bring up a good point. The humor…the level of consciousness, if this is a term. Humor, the smart humor about–

(laughs)

“I was so proud of all y’all folks, how you made that funny? How?”

But it’s so accurate! It’s so funny!

DS: Tonika, to your point: this fall [2020], when the meme of landback came out, one of my homies showed me, she showed it to me and I literally fell on the floor. It said, “Republicans are like ‘fuck poor people.’ Democrats are ‘fuck poor people, she/her/hers.’”

(everybody laughs)

What? There you are!

TLJ: But we should do… we should make a book! Collect all of these memes…

DS: Man! That was it! I was like, damn! Hell no! You summed up all of the political strife in like, a hundred..

TLJ: A hundred characters.

DS: A hundred characters! Right! I was like, damn! That’s it.

TLJ: I’ve been really proud of the humor that has emerged out this past year. I love it. Protest humor. Is that a thing? Protest humor! I love it.

They should really attribute [memes], cause I want to follow these people! Literally, when it started to happen, I was like, “Okay these people are too funny and smart! Who are they? Who made this meme? I want to follow them and be their friend!”

But yeah, OK. Next question please.

PVO: How do you think education needs to change now?

DS: Well, look, Percy. This is what we know. We know that standardized testing is a fraud and a farce. It’s been a fraud and a farce for almost a hundred and fifty years. We know that no young person has died because they didn’t take a standardized test.

Now, you’ve got a moment. They suspended standardized tests and the state of Illinois applied to the feds to get a waiver not to take them. Just get rid of this shit! I mean they were never needed! And something that was actually born out of eugenics. Standardized testing was created because of a belief of non-white people to perform lower. They wrote the scales based on the belief, so that’s something that we could easily be getting rid of. And if you think about it even more radically, what if we start to think about grading differently? Why do we even have [grades]? Because grades, if we really come to this point of reckoning, [are] really about you demonstrating your capacity to regurgitate your proximity to a knowledge of white Western enlightenment thought. So, you’re graded on how well you can regurgitate your proximity to whiteness.

So, now that we think about that, what would it mean to have different forms of assessment that other countries actually use! This dude, about twelve years ago, came from Brazil who did these things in a town called Porto Alegre, [called The Citizen School Project (Escola Cidadã)]. He came to Chicago, and he was walking in the hallways of the schools and people were explaining to him what grades were and he came to us and said, ‘What are y’all doing? You are still ascribed to a system that separates folks before it puts them together.’

So now you have an opportunity–back to your question, Percy–now you have an opportunity to revisit that, to do that differently, and the window is small, that window closes very quickly. But at the same time you have a way to rethink what some of the things are happening.

The last thing: getting cops out of schools. Right now, we know that cops do not make young people feel safe. We also know that the presence of cops does not decrease crime. What it does do: it increases arrests. So this thing, we have some things that we could readily do that would be substantive changes to how we understand education.

TLJ: I agree with David wholeheartedly. And I think that an upcoming opportunity for us to rethink the value, the assessment, the criteria for certain grades is approaching very quickly. Because honestly, as a parent of a high schooler–a 2020 high school grad and sophomore–there are kids that did not do well during this period of virtual learning. My son, one among them. He just started failing three months ago. This is affecting their grades, their actual GPA, so next year there are going to be parents who will want to protest their kids being impacted by the grade that they’ve gotten during this pandemic because that sticks with you if you want to go to college. I had to advocate for my son, my son being actually diagnosed with anxiety. I had to advocate for that to help him get a 504 plan. Something I know nothing about, but I have friends who are educators who told me how to go about it, because of the fact it’s going to affect his grades.

So how grades are used [and] what they are used for,is completely unfair, not only just the curriculum in general, just everything needs to be…a complete overhaul. There’s a time that will be fast approaching in regards to grades students have gotten during the pandemic that can be used as a platform to, at least, start a conversation [of] us really discussing the inequity of the grading system.

I just agree with what Dave said, and I’ll start whatever petition, do whatever protest, and abolish grades! Because they definitely don’t speak to my son’s skillset or the brilliance that I know of him. It’s just another way of getting stereotyped and misjudged.

FP: So I’m Anishinaabek. I’ve got ten kids point-blank. Two of them are out of school thankfully, but the other eight are in school. And then on top of that, I’m an auntie to youth council with kids navigating high school or lack thereof. So one of the conversations I had with my circle is are we okay with letting our kids fail? And we had to check ourselves because it’s not the kids that are failing, it’s a system that’s failed them. It’s always failed our kids. At what point [do we] as Native people, as people of color, become okay with sending our children to white supremacist institutions and expecting them to come out whole people. So thankfully one of the bright things that came out of [remote learning] is we were able to really understand what they were taught in school ‘cause we could hear it. One of my nephews is a freshman in high school. His teacher told him that Western expansion was not a genocidal act.

That nephew is white-passing. So I think it’s the way in which the teacher had coded my nephew and assumed that would be a satisfactory answer to move on from the class. I’m just looking for those opportunities to do unschooling, not only for our youth, but for parents, and actually teaching ourselves how to re-parent ourselves and be better parents for kids. The word “failure” when it comes to academic learning should never be applied. We have to understand that our children are individuals but they’re part of a community, and communities shouldn’t turn and point at someone and call them a failure for trying.

PVO: What are you personally nurturing in your life at this time? I understand that this is turning into a little bit more of a vulnerable question.

DS: This notion of nourishing space of willing, being in communication with each other, because we’re seeing folks who unexpectedly are passing away. Then we got the heightened moment of Covid, of not being in community with folks so for me it’s really understanding what it means to be in community with folks, because many of those folks who I expected to be in community with are no longer here. So that to me is the reminder, right?

What does it mean to live fully with ease and care, but also what does it mean to live fully [while] understanding that there is work to do. People talk about revolutionary love, but it’s another thing to live that, to really understand it, because in some ways the world keeps moving and because in other ways we see this shift. Now personally, we have to figure out: how do we slow ourselves down to figure out what those next steps are? Because the world moves so quickly, right? If we pay attention to that in a particular way, it will appear as if the world it’s moving at a higher speed. What are the ways to slow down? I really think about the ways I slow myself down and pay attention, and what I’m paying attention to because you can get into these heightened moments of hyper-vigilance. I’ve been trying to nourish and pay attention to the things that I hold close. And that is a real labor in this moment.

FP: I think one of the things, especially this past week, that I am learning to nurture is the creation of boundaries. Stovall said it. Trying to come back and nurture this idea of community has been what I’ve been focusing on for so long, but through this past year [I’m] understanding that community should hold the same values.Just because I have similar political designation as a Native woman to other Native people, not everybody has to be in my community. I don’t have to sacrifice myself or our youth in order to try to put Band-Aids on wounds that are too deep for people who refuse to reckon or reflect on their actions.

TLJ: I’m just learning to nurture my sanity more, and my children. I have a sixteen-year-old and a nineteen-year-old so I really had to shift my focus on helping them navigate

(laughs)

all of this, as well as trying to establish a space for them to experience the last little bit of true youth freedom that unfortunately isn’t afforded to Black kids, especially as they move into adulthood. They start to experience all these horrors of racism that creep into their lives, and I just want to preserve the sense of carefreeness that my rearing has allowed them to tap into, ‘cause a lot of people assume, “Oh! you do all this community work, I know your kids are like young activists,” and I’m like, “No!”

I want them to not think about this as long as possible.

(laughs)

I want them to just be bathed in Blackness, to be proud of it, to be proud of where they come from, literally from this neighborhood, to know they are represented but, they don’t have to stay here if they don’t want to. They can if they want to. You are supposed to be learning about yourself and learning how to be in community with others through friendships. That’s really the only responsibility that you should be having.

(laughs)

Everything beyond that is absolutely crazy. I look at my nineteen-year-old and I cannot believe–speaking of Education–I cannot believe they want people this age to pick a major! To figure out where they want to go for school. To put that expectation on the whole entire age group. Yes, for those who have a passion and know it, yes! But I don’t like this. For me, nurturing them has helped me see all of the other ways in which so much in this country needs to just be like: burn the hill down and build it back up, you know. Education’s one of them. And just how culturally, even.. [education] is rooted in white supremacy, and how they’re psychologically perceived and engage with the world, our culture over here as westerners reflect that, but it’s so problematic, it’s so individualistic, and it really doesn’t allow people to discover themselves. Once you have time to do that then you can start to discover the ways in which you have been programmed to be racist or anti-whatever, and it’s just our culture of busy-ness, our culture of just capitalism: just having, ‘you should have this by this age.’ Even housing as a commodity! All of these things are like golden staples of your life you should be trying to get to. And it’s just a mess, so I’m just really trying to nurture these moments in time for my kids where they can just be the individual teenagers they are. Be as much as you want right now. If you don’t want to talk about it, anything political? Fine, don’t. If you just want to talk about how your friends get on your nerves? Fine, let’s do that, ‘cause trust it’s gonna end.

PVO: Is there anything or any lingering thoughts that you have that you want to share?

TLJ: I just want to hang out with everybody!

(laughs)

DS: Look! Look Tonika! I said it to a couple of homies yesterday. Literally, I’m going, when shit is finally declared over, I’m gonna go to a cafe and sit in the window for the whole day, like just support the homies at the counter and just be in the window.

TLJ: I’m not saying no to nothing!

DS: I’ll just be in the front of the cafe, I’ll turn myself into a cafe greeter. “Look! Y’all good? Enjoy yourself, you know, it’s a nice day out. Enjoy yourself, do some shit.” I officially see myself turning into people from Seattle. If you ever go to Seattle they do this shit like when the sun comes out. People start freaking out! They start actually like, “What are you doing today? The sun is out” And I’m like, “What the fuck!” It’s just random people having conversations. And it was really connected “The sun is out! What are you doing today?” So look, that’s real life! I’m gonna go to one of them joints, I’m standing up and waiting all day. I’m not doing an inch of work, just being in the fucking window.

Persephone Van Ort is a trans, white artist and writer living in colonized Chicago. They are the associate artistic director at the Prop Thtr. Their work has been featured with the Neofuturists, Walkabout Theatre, and others. They write about time, crisis, and dreams. You can find more of their work at jayvanort.com.