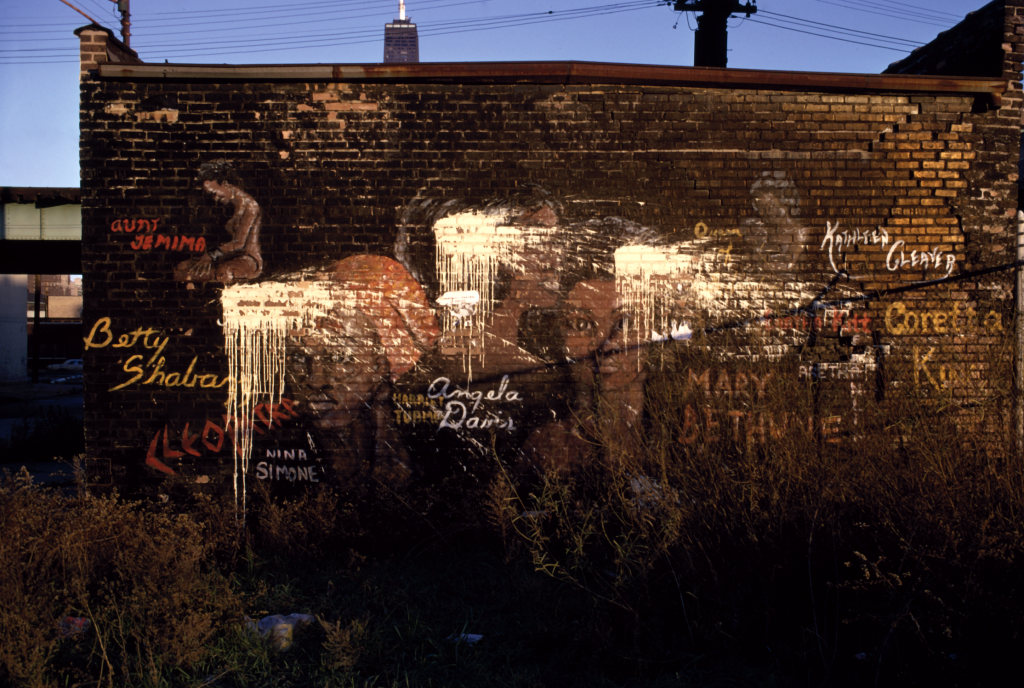

Featured image: An industrial street corner in Chicago, in the foreground is a small brick building, painted on it is Vanity Green’s mural. Vanita Green, Black Women / Racism, 1970. Mural at Chestnut and Orleans. Photograph by Mark Rogovin. Courtesy of the Georg Stahl Mural Archive, University of Chicago Visual Resources Center Luna Collection.

I pondered Tina Campt’s phrase, from A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See, “occupy a space on their own terms.”1 While her statement referred to the inter-sculptural gaze of Simone Leigh’s work in Loophole of Retreat, this Black Feminist practice resounds in many artists’ practices. “Occupy a space on their own terms” holds space and claims sovereignty. In essence, it allows a rupture of the space-time continuum and enforces an omnipresence. Or my momma would call it—stand in the gap. Vanita Green occupies a space on her own terms with Black Women / Racism, a mural on a storage shed on the Northside of Chicago that celebrates historical and fictional Black women. Shortly after the mural’s creation, it was defaced, further symbolizing the power of claiming space and radical preservation.

Critical fabulation2 was a crucial research methodology because archives, repositories of memory, re-enact colonial power structures. While the colonial imaginary may value written information, an Afrocentric paradigm, especially Black Feminist Afrocentric lens, investigates the visual, spiritual, material, auditory, and unlocks the overall kinesthetic experience. Critical fabulation acknowledges what archives render invisible and how they disrupt notions of belonging. For this research, formal visual analysis, synthesis of archival information, and reaching out to many sources provide avenues to sensing Green’s spirit through interpreting factual subtexts. Green’s name appeared in Lisa Farrington’s African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History. From there, I reached out to the Bronzeville Historical Society, who referred me to Rebecca Zorach, the Mary Jane Crowe Professor in Art and Art History at Northwestern University. She connected me to Georg Stahl, who photographed Vanita Green’s mural, and he put me in contact with Bridget Madden, the Associate Director of the Visual Resources Center at The University of Chicago in the Department of Art History. Madden connected me with another image rights holder, Michelle Melin-Rogovin. All along the way, I gathered information about Green.

Black Women (1970) was a public art intervention that claimed space denied to Black women, yet many art historians overlook both the artist and the mural. When the project began, Vanita Annette Green (b. 1952)3 was seventeen and a resident of Cabrini-Green Projects.4 The work appeared on 861 N. Orleans St. (corner of Orleans and Locust) on the Northside of Chicago.5 Black Women emerged near William Walker’s mural Peace and Salvation: Wall of Understanding. Walker’s mural is one among a series of murals throughout Chicago with aspirational value titles such as Peace, Wall of Truth, and Wall of Respect. This mural addresses violent societal landscapes and hope for unity. It demonstrates this by a depiction of a dove at the top, a ribbon wrapping around with four hands reaching towards each other, and a central group of Black male peacemakers, such as Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Jesse Jackson, Malcolm X, Black Panther Party members, John Stevens, and local Chicago youth group community leaders. However, among the Black iconic figures, women were excluded. Lisa Farrington writes, “Observing that [William Walker’s] mural portrayed men almost exclusively as arbiters of “peace and salvation,” Green borrowed Walker’s paints and brushes.”7 This act of defiance carved out space for Black women in the narrative of community building.

Green’s work highlights Black female historical and mythological figures: Betty Shabazz, Nina Simone, Cleopatra, Harriet Tubman, Angela Davis, Coretta Scott King, Kathleen Cleaver, Mary McLeod Bethune, Eartha Kitt, and Aunt Jemima.8 The completion of the mural Black Women was accomplished after weeks of labor Green completed at night after working another job during the day.9 Each woman depicted appears alongside text, varying from white, red, yellow, and orange pigment and an array of different hand-painted font styles. Green’s illustrations and annotations appear without a painted background. Not including a background removes specific context: space, time, and location. This timeless shows a continuation of Black female historic figures — some busts, some full bodies.

What is most compelling are the multiple gazes within the painting. A few figures suggest an interior gaze by facing away from the viewer. For example, the figure next to the name, Aunt Jemima sits in repose, cross-legged, and head-bowed facing away from the viewer and maintaining an inward gaze. Aunt Jemima’s nude body shows attention to a light source emanating from the center. The right-hand corner, next to an obscured name, depicts a woman holding a child, her eyes are imperceptible. The array of gazes and sizes of the female figures showcase a diagonal rhythm and depth of field. Overall, some figures face straight-on, others ward off direct eye contact with their gaze. Their shielded gaze and refusal maintain a quiet power.

Black Women galvanize the philosophies of the Black Arts Movement by representing a working-class Black perspective. Green oriented her work around Black power and liberation, cultivating a Black agitprop aesthetic, and making accessible work.10 Her work caters to the public because it is a mural for public consumption. This mode of display affirms the community. However, public display precipitated public interaction and scrutiny. A few days after completing the mural, white or yellow paint (color variation across sources) covered the mural by an unknown defacer.11 In 1977, Eva Croft wrote that this was “practically the only defacement in Chicago at that time.”12 Therefore, while the motivation of the defacer is unknown, their choice of destroying a mural that celebrates the contributions of Back women, communicates power that compelled their defacement. In response, Green retitled her work Racism and stated to Eva Cockcroft, “It says more the way it is. Before, it was just a bunch of pretty pictures. Now, people have to stop and think. Why would anyone do that to a painting?”13 Green’s assertion and re-titling of the mural suggests a Black feminist consciousness because of her proclivity for self-naming and noting that the change in her image directly interacts with her intended message.

Years later, with considerable gaps in the archive, Green obtained a bachelor of arts degree in June 1976 from Columbia College.14 The next record of her Green is that she (possibly) died in 2011 at age 58, which Rebecca Zorach, professor of art history, shared.15 A profound melancholy clouded the remainder of the research eliminating the likelihood of meeting Green and witnessing her personality. It was another instance of the transfiguration of a riotous woman, in the endearing way that Hartman bestows the term, absent in the body but an alive spirit. There was so much knowledge worth uncovering. Who commissioned her for Black Women / Racism, did she make any other murals in Chicago, and how was her life? I thought back to how Vanita Green’s work belongs to a long lineage of iconoclasm of Black women in art history. Ancient Egyptians believed that one’s spirit or “ka” resided in figural sculpture.16 When Hatshepsut, the first woman sovereign pharaoh of Egypt in 1473 – 58 BCE,17 passed, her successor destroyed statues depicting her.18 Therefore, iconoclasm erased memory and staged spiritual warfare. Similarly, Vanita Green occupied a space of her own by rending the lives of Black women visible defying erasure. Though paint obscured her work, may we bear witness to her beautiful resistance.

* * *

Works Cited:

1Campt, Tina. “Sounding a Black Feminist Chorus,” A Black Gaze, Artists Changing How We See, (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2021), 147.

2Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14. muse.jhu.edu/article/241115.

3Farrington, Lisa. African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 256.

4Cockcroft, Eva. “Women in the Community Mural Movement,” Heresies: A Feminist Publication vol. 1, no. 1 (January 1977), 14.

5“Racism,” Chicago Mural Movement Project, Northwestern University, n.d. http://madstudio.northwestern.edu/ChicagoMuralMovement/#!/list/5877

6“William Walker Peace and Salvation: Wall of Understanding,” University of Chicago Visual Resources Center, n.d. https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/ll/thumbnailView.html?startUrl=%2F%2Fluna.lib.uchicago.edu%2Fluna%2Fservlet%2Fas%2Fsearch%3Fos%3D0%26q%3DWilliam%2520Walker%26bs%3D100

7Farrington, Lisa. African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016, 256.

8Ibid.

9Zorach, Rebbeca E. “Climb the Scaffold”: William Walker, Mentor of Women Artists,” Bill Walker: Urban Griot, Chicago, IL: Hyde Park Art Center, 2018, 35.

10Zorach, Rebecca. “Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975,” Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019, 5.

11Farrington, Lisa. African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016, 256.

12Cockcroft, Eva. “Women in the Community Mural Movement,” Heresies: A Feminist Publication, vol. 1, no. 1, (January 1977), 14.

13Robbyelee, “Vandals Destroy Mural: It Makes You Stop and Think,” Liberation News Service, January 27, 1971.

14“1976 Commencement Program,” Columbia College Chicago Library. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/commencement/11/

15“Vanita Green,” n.d., White Pages. whitepages.com

16Calvert, Amy. “Ancient Egyptian Art,”Khan Academy, n.d. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/ancient-mediterranean-ap/ancient-egypt-ap/a/egyptian-art

17Tyldesley, J.. “Hatshepsut.” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 1, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hatshepsut

18Pobric, Pac. “Unearthing Hatshepsut, Egypt’s Most Powerful Female Pharaoh,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/collection-insights/2018/hatshepsut-female-pharaoh-egypt

Chenoa Baker (she/her) meditates on Black art, hybridity, ecology, spatial studies, and collective liberation in her writing and curatorial practice. Currently, she resides on the ancestral homelands of the Massachusett, Wampanoag, and Nipmuc peoples as a Museum Fellow at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. Her work appears in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Burnaway, Art & Object, Black Art in America, and Sugarcane Magazine. Learn more by connecting with her through LinkedIn, Instagram, or email.