This article is part of a partnership between Sixty Inches from Center and Black Lunch Table (BLT) partnership, Crowdsourcing the Canon—an editorial series diving into the lives and practices of Black artists based in the Midwest, especially those whose Wikipedia pages lack sufficient citations.

Note: All quotes not otherwise cited were spoken by Yaoundé Olu in a conversation between Nadia John and Yaoundé Olu recorded on April 19th, 2025.

Early Life

In 1945, the same year World War II ended, Yaoundé Olu was born in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood and lived in the rectory of Saint John Church. Minus a stint on Grand Boulevard and suburban Illinois as an undergraduate, she has always stayed on the South Side—Englewood, South Shore, or Hyde Park to be exact. Her family had a penchant for moving into a neighborhood just as it was transitioning. Englewood was historically a white immigrant, working-class neighborhood. Its early housing, built in the early 1900s, was made to house the workers who came to work for the Union Stock Yards and steel mills in the area. Beginning in the early 1940s, Englewood and surrounding neighborhoods were also taking in many new residents that moved as part of the second wave of the Great Migration, who were also taking in the spaces left by drafted residents in WWII.1. By 1940 the housing in the neighborhood, which was largely bungalows and hastily built apartment buildings, started to fall to disrepair, so the available housing became some of the most affordable in the city, and able to house its influx of new residents who came to start a new life. Englewood, and its surrounding neighborhoods such as Kenwood and South Shore, which brought in Black residents from The Great Migration as early as 1910, soon became known as “The Black Belt” and by more derisive names, such as “Black Ghetto” and “Darkie Town”. With this influx of new Black residents came reactionary white flight and redlining from the previous White residents. The 1948 Shelley v. Kramer United States Supreme Court case ruled that “racially restrictive housing covenants (deed restrictions) could not be legally enforced,” which further exacerbated the white flight and redlining2. Englewood had a “population of 98 percent White residents in 1940, but by 1950 the population of Black residents increased to 11 percent, 69 percent in 1960, and 96 percent by 1970”. It now has a population of 90.5% Black residents, per the 2024 Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, and a similar trend in population change can be said for other neighborhoods in “The Black Belt”.3

Birthed in such a context as The Great Migration, the Black Belt became a site for Black communities to start anew and flourish, as well as a site of great political and economic struggle, as redlining left increasingly deleterious effects over time. Olu says everyone on her block ended up being teachers and preachers, or (later on) gangsters as the neighborhood transitioned again in her adult life.

Olu’s father was born in Cincinnati, Ohio and moved to Chicago when he was a child. Her mother was born in Wichita, Kansas and raised in Chicago. Her father went to the oldest predominantly Black high school in Chicago—Wendell Phillips Academy. Her mother went to DuSable High School where she was part of the first class of students after it was built. Her father was a mailman. Her mother worked for the Social Security Administration as a clerk. Her parents, like Olu and many others in her family, did not just stick to one career; they had other jobs on the side. Her father was a carpenter and painter. Her mother was also a novelist.

Olu comes from a family of six children. She grew up with two siblings and when they grew up, her parents had three more children. Olu was the oldest and got along quite well with her siblings.

One of her earliest formative memories was when she saw an airplane while walking with her grandfather when she was three years old. It was rare to see planes in those days. To Olu, the big machine flying in the sky seemed like an extra-terrestrial and marked it her first encounter with something that could continue to inspire her throughout her life.

Olu describes her family as mystical, invested in learning and interested in culture. Her house had a lot of nice encyclopedias and many books. They were also people who had to have personal freedom in whatever they were doing. When she was growing up, her paternal grandfather was a preacher ordained in the Church of Christ and a Master Freemason connected to a “whites only” lodge. Olu would often hear him describe his philosophies toward life and share his prophetic visions in ways that sound like riddles or have varied interpretations. These prophecies would often be about incoming changes in daily life through new technology, tensions and shifts in politics or racial relations, and shifts in humanity’s personal and collective philosophies. She remembers he would say things such as, “in the end, there will probably be a skirmish between white and Black, and that no white and red and the Black would be the determining factor as to how the planet, how the world turns out.” Most of the men in her family growing up were also Freemasons. Olu and her siblings absorbed this mystic lineage. The manner in which her grandfather would speak of philosophical things and tell stories gave her and her siblings the understanding that “there are things that you can know that everybody else doesn’t know and let us know that there is more to life.”

More in that vein, Olu describes her family dinner table as “more like a conference, because whatever wasn’t dealt with during the day or whatever was dealt with, you know, that’s where we would take care of our issues. Right there.” This would influence her to be preoccupied with larger philosophical questions throughout her career.

Olu also described her family as accepting and insisted she and her siblings were encouraged in their creativity: “I think there’s a certain amount of comfort that comes with being able to be yourself. You know, in my family, everyone, you know, everyone can be whoever they are. And I love that about my family.”

Becoming an Artist

Olu wanted to be an artist from a young age and was particularly drawn to cartoons from the murals her father made and the visions she had since she was little. She mimicked her father, his cartoons, and drew people and things she saw. She showed her parents and they kept nurturing her early talent and passion.

Mentorship was and is important in Olu’s life as a creative. Olu’s parents were her first mentors, encouraging her work in subtle direct ways by giving her art supplies or offering advice. “I’ve had several teachers who were mentors. And like, when I started teaching, I had mentors. In fact, all through my career, I’ve had mentors. And when I say mentors, these are people who liked what I was doing and thought I had potential and who tried to make opportunities for me so that I could, you know, manifest what it was that I wanted to do.”

She got more serious about being an artist over time. After studying books about famed artists from her family’s bookcases, Olu began working on her own art portfolio when she was 12 years old. Olu is largely intuitive and describes a desire to be in control of how she decides to spend her time. She also desires the freedom to explore. The first time she felt like she could really make it as an artist was after she submitted work to a magazine drawing project, but was not able to qualify only because she was below the age requirement specified in the contest. Being told that she had to wait until she was 18 to be a professional artist put a damper on her early aspirations so she ended up channeling her energy into music and her other interests such as writing and science.

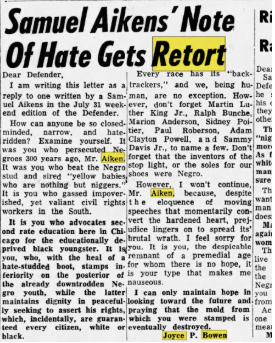

Growing up within the context of The Civil Rights Movement and the racial tensions caused by white flight in South Shore and neighboring communities, Olu was socially conscious from a young age. For example, The Chicago Defender, one of the oldest and longest-running Black newspapers in the United States, which counts Willard Motley, Langston Hughes, and Gwendolyn Brooks among its past contributors, had a large presence in Olu’s neighborhood growing up.4. The writing was often political and moralistic. It campaigned against Jim Crow, was distributed with the help of Pullman Porters, and had a large effect on Chicago being seen as a spot to move to during the The Great Migration.5 The newspaper also established a club for youth in 1923, the Bud Billiken Club, for Black children through the “Junior Defender” page of the paper. It was similarly moralistic, but written by youth and made specifically with Black youth’s development in mind. In 1929, the organization began the Bud Billiken Parade and Picnic, which by the 1950s became the largest single event in Chicago, and is still one of the largest parades in the United States.6 Off-and-on Olu wrote and contributed to the youth section, first offering her reply to brief street interviews in articles penned by older folks and then on to contributing her own writing, in the teen section titled, “Defender’s Younger Set”. She is quoted in the January 20, 1962 issue of The Defender talking about her participating in a high school play to test out her acting skills: “I’ve always liked all types of acting, and I feel this group will help me develop the ability I have”(pictured below).7 In the August 1965 issue, she penned a rebuff to a racist Op-ED left by reader Samuel Aikens (pictured below).8

As a student at Parker High in Englewood, Olu kept pursuing her interests outside of visual art and she won second prize in a citywide science high school contest.

She also discovered a passion for making music by testing out a drum kit in the school band room, but was discouraged at first from playing drums in the school band because drums were seen as a “man’s instrument.” Her mother encouraged her to take up the clarinet. For her work on the clarinet, without intentionally setting her mind to it, she won a John Sousa Award in 1964, the highest honor for high school musicians. “I had no idea. I didn’t know, I didn’t even know they paid attention to you in school. You know, some people may enter programs with a goal for A, B and C, but with me, I was just doing what I enjoy doing and what I wanted to do. So I was a member of the band, and when I graduated, I got the John Philip Sousa Award.”

Beyond the help and encouragement of her parents, she credits her high school arts teacher Frank Smith (b. 1935-2025), (a venerated artist in his own right, as giving her a great early education in the arts. He encouraged students to bring themes of politics and personal identity into their working, giving pieces a weightier meaning while encouraging personal style. She was often surrounded by venerated people such as Smith, but did not know they were world renowned.

The first time she exhibited her visual art was in high school. She made a painting inspired by Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech after watching the March on Washington on television. She saw art in one of the windows of a jewelry store at a shopping centre on Halsted at 63rd. One of the storekeepers let her exhibit her timely painting. This gave her confidence. She had a real piece of art in a real store.

College years

The theme of mentorship continued to be a central part of her life: “I had older people around me who encouraged me to do what I was doing. So that was important. And in fact, everything that I’ve ever achieved and accomplished in, in various and sundry areas, was because I’ve been fortunate to have people who might be called the ‘wind beneath my wings.’ These were people who really were interested and impressed by what I was doing and encouraged me. I did have people who took me under their wings. I’ve always had mentors and fans in everything I’ve done.”

This inspired her to become a teacher after graduating high school and mentor the next generation. “It’s crazy. I’ve always had mentors and because of that, I know how important being a mentor is,” Olu said.

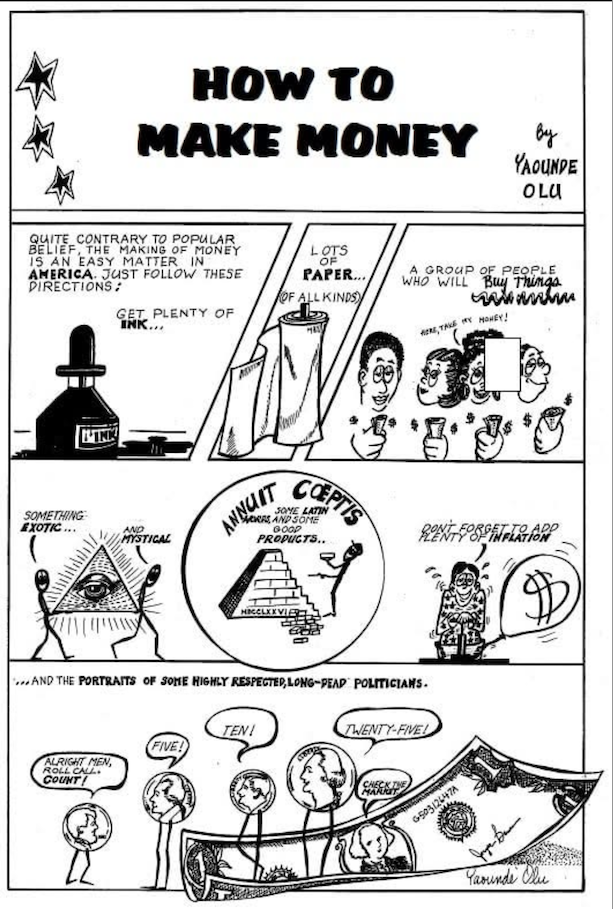

She first went to Illinois Teacher’s College, Chicago South to get a teacher’s degree and started teaching science in January 1966. There she drew comics for “Tempo,” the school newspaper. (Also, she was humor editor of her school newspaper for the student paper when in third grade). Word of her talent got out and eventually she was writing comics for Ebony Jr. magazine—humorous comics that contained a lesson. She was making paintings and drawings of her own at this time.

Eventually, Olu became close with a fellow teacher and running buddy during her first teaching job. Her friend was also an artist and encouraged Olu to start exhibiting work. Seeing how her fellow teacher was able to juggle these two careers made Olu realize that this was possible for her as well. Olu started to exhibit her work more regularly. After college she took her first trip outside of the United States and backpacked through Europe, seeing some of the most world renowned museums, including the Louvre, which inspired her. She eventually received an MA in Fine and Performing Arts from Governors State University in 1980, and a PhD in Health Sciences/Holistic Medicine from the Union Institute in 1994.

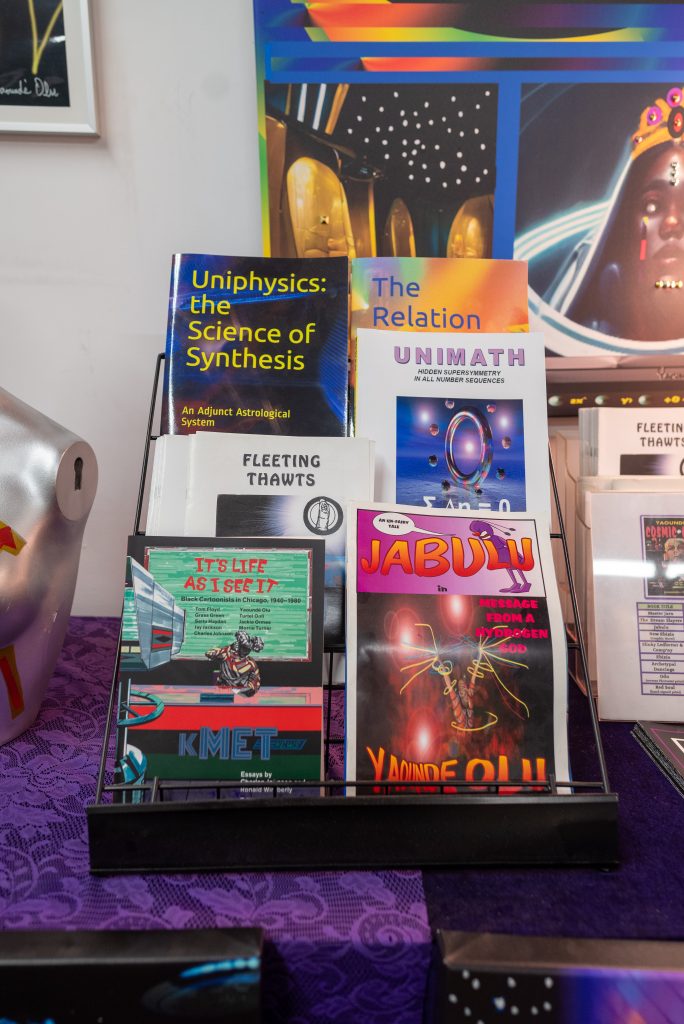

While still a teacher and a working artist, Olu became an astrologer after picking up a book on a whim while sick at home. This became another angle to ask the bigger questions regarding life. She has authored books on astrology, mathematics, and metaphysics including “UniMath” and “Uniphysics”. UniMath and Uniphysics are described by Olu as the following in her book, the Science of Synthesis: An Adjunct Astrological System (2020): “Unimath is a mathematical tool used in Uniphysics, the Science of Synthesis. It analyzes the increments between numbers in numerical sequences, and has found an amazing Law of Digit Balance wherein all sequences sum to zero with resulting balanced binaries, creating mirrors with more than 60 digits. It also reveals amazing, non-random patterns in the digits of pi, e, prime numbers, Lucas numbers, Fibonacci numbers, and more! Unimath opens up a whole new avenue in the field of number theory”.9 She also published a book that reveals the origin and generation of prime numbers (Prime Patterns: Neoteric Patters in the Prime Numbers. 2020) and another one, “Ben Franklin’s Most Magical Magic Square: New Analysis.” 2008), both under Joyce P. Bowen).

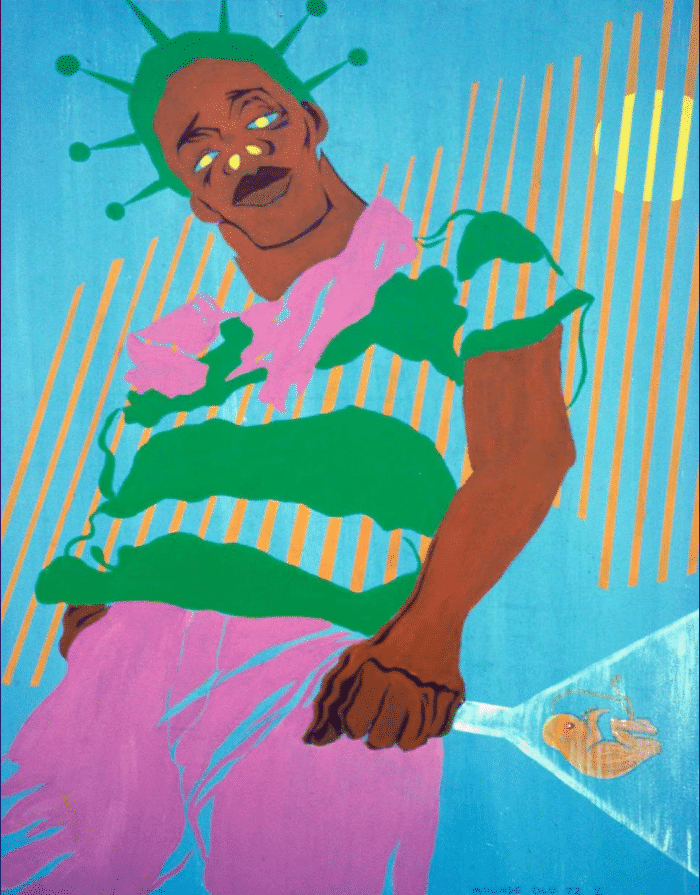

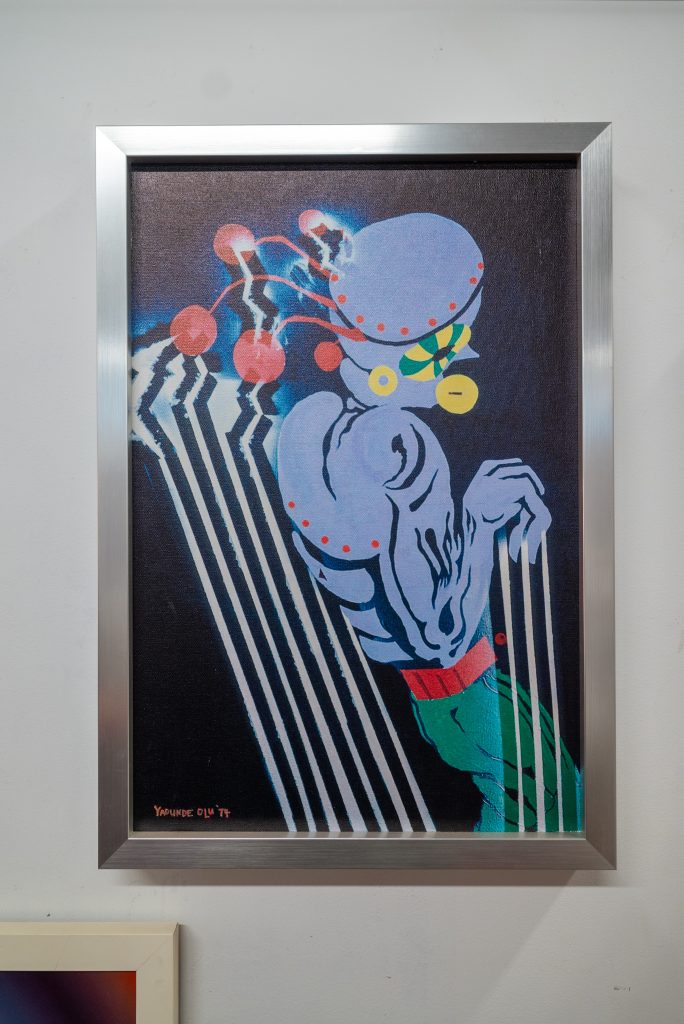

The interest in physics, metaphysics, philosophy, and structures within society can be found throughout her work including her painting “The Magician” (1974) and “The New Magi”. Both of these works were done in acrylics and show one of the entities with body paint and drawn in such a way to look African, and transmitting or being infused with energy coming from a possible world that they live in or visiting a world different from their own.

On Her Signature Style

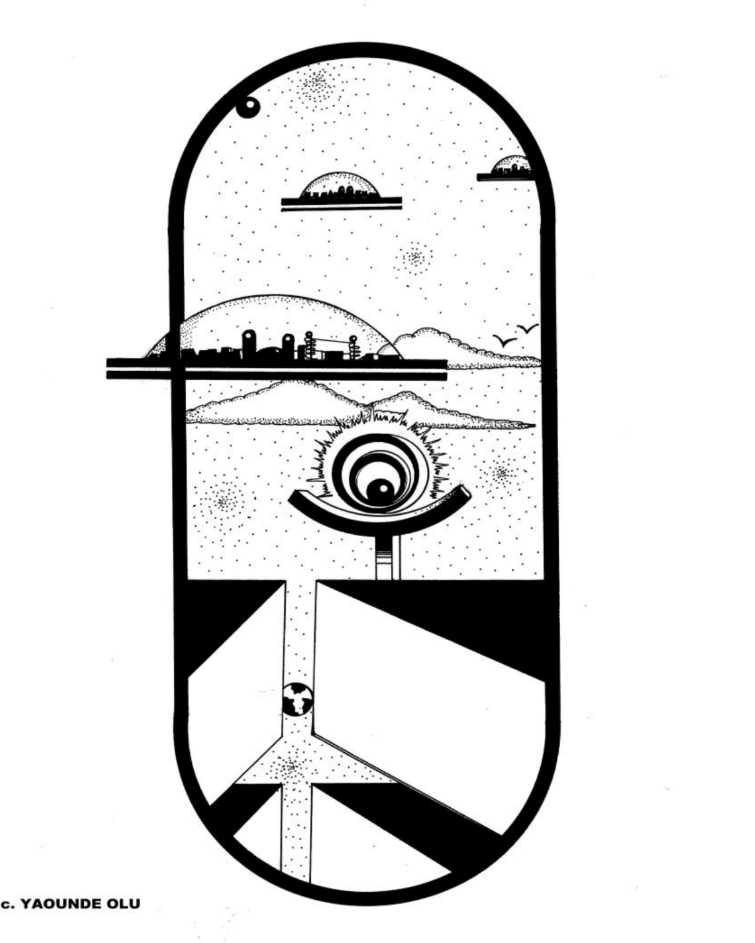

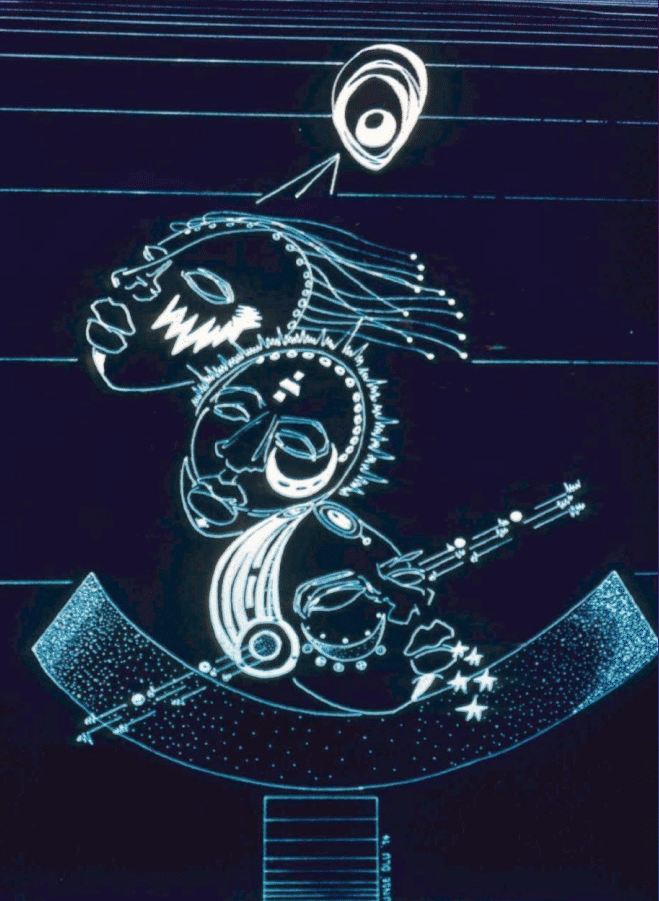

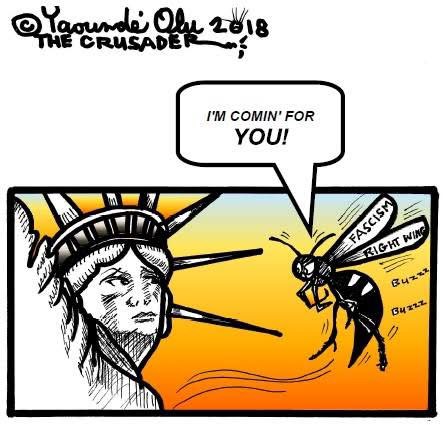

Olu has always had a specific style or flair to her work across mediums inspired by her upbringing and by the visions of entities she has had since she was little. These entities may exist now, did exist, and/or do exist in another dimension. Her work overall and specifically her cartooning always has a bit of the idiosyncratic, infusing her personal interest in harmony, the larger questions in life, political meanings of current events, equity, and a nontraditional abstract flair. Aside from her editorial cartooning, she describes her work as “Retrofuturist”.

Her 2022 show at Evanston Art Center, titled Black Field/White Field, included digital drawings/paintings/mixed media constructions on canvas, photo paper, and laminated prints. In her artist statement for this show, Olu defines “Retrofuturism” as follows:

“My art is designed to portray an alternate worldview distinct from everyday life, but that provides an objective mirror through which our lives can be seen. It takes us on a journey to unfamiliar, yet familiar territory, wherein the imagination presents numerous possibilities about different ways of being. This visual poetry strives to bring a bit of light to the world to counteract the heat that divisiveness generates; the idea of wide-ranging existences can possibly highlight the senselessness of the “isms” that tend to exacerbate that divisiveness.

My art is termed “Retrofuturism,” which could be considered as a subgenre of Afrofuturism. Retrofuturism represents images from the ancient past, elsewhere in the present, and the future”.10

“Afrofuturism,” was coined by cultural critic Mark Dery in his 1993 essay “Black to the Future.”11 Dery used the term to describe the intersection of Black literature and technoculture, exploring themes of Black identity and futures and put them into conversation with the Western artistic movement, “Futurism”, which was an avante-garde artistic and social movement founded by 1909 by Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and embraced the technological advancements of humanity which triumph over nature.12 This term quickly grew in usage within the Western art world. Although the term is still used today as the title for books, exhibitions, and used to describe the works of artists, such as Sun Ra and Flying Lotus, criticisms of Dery’s term and concept quickly arose, particularly from Black artists whose work it was said to describe. The term has drawn criticism from Black artists and culture workers because it emerges from a Western and colonial perspective of art; the term was not coined by a person of African descent and work by the Black artists it describes wasn’t intentionally made with the term in mind. When contrasted with Futurism, which was founded by a Italian Nationalist poet i.e. Marinetti through a manifesto that other Italian Nationalist artists agreed to sign, it’s hard to not see that the term “Afrofuturism”, coined by someone from outside the lineage of the work that there is a dialectic between the terms where artists and cultural workers have the say in the definition of their work, whereas the historically marginalized have much less of a say in their rights to autonomy. Echoing this statement in an article for the Chicago Reader, “The Time is Now! celebrates the black artists of the south side who used their work as a vehicle for social change” published in 2018, curator and Sixty Inches from Center founder, Tempestt Hazel, argued that terms labeling Black artists, with terms like Afrofuturism, “[strips] them of the opportunity to exist within a community-grown context created by, for, about, and directly from the lineages of Black diasporic cultures”.13

Olu started making work in her style before Afrofuturism existed as a term, but the otherworldly and “futurist” style of her work and the subjects presented have often been lumped into Afrofuturism. Another reason this term has drawn criticism is because it dampens the idea of Black genius and pits futuristic ideas in a dialectic with modernism and the avant-garde, both which are a result of colonialism and cultural reappropriation of various Black cultures.

Oşun Center for the Arts + The Black Arts Movement in Chicago

In the mid-1960s Chicago became a hub for The Black Arts Movement (BAC). Originally founded by New York-based poet and playwright Amiri Baraka in 1965, it evolved from conversations had when he opened the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BARTS) in New York following the assassination of Malcolm X.14 The BAC was inspired by the Black Power movement and Civil Rights Movement and intentionally expanded upon the accomplishments of artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Word spread of this movement, eventually inspiring artists in other cities like Chicago to create work with Black liberation in mind. It was a time when activism and art by Black artists combined to create new cultural institutions and styles across the various artistic disciplines that emphasized Black pride and reflected the African-American experience in a modern way. There was an emphasis on the tenets of Black Liberation, particularly self-determination for the Black community. Jeff Donaldson (1932-2004) who was closely associated with Chicago-founded BAC organizations such as the The Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) and African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AFRICOBRA) in the mid-1960s, described it as a time where Black artists strategized ways to work together across-genres to create “positive images with positive feasible solutions to [Black people’s] plights”.15 Collaboration, exchange, and shared inspiration was in the air for Black artists at the time.

In the late 1960s, along with the Black power movement, Black folks changed their names to reflect their heritage and religion, rather than their colonized name. Yaoundé Olu went by another name prior to 1967. Shortly before starting her gallery, Olu picked her name with a friend. They both closed their eyes and picked a spot on a map of Africa. Olu’s map landed on the capital of Cameroon: Yaoundé, which means “mother returns”. This name became a way to embody a new version of herself as a Black person in the United States and as an artist.

The organizations in these movements that operated on a national level, inspired change and civic engagement at a neighborhood level. Organizations such as the Woodlawn Action Committee, were formed with the intent of stopping “Urban renewal” campaigns and the disenfranchisement of Black majority schools.16

Simultaneously other movements sprung up such as the Women’s Liberation Movement, which had a chapter in Hyde Park beginning in the early 70s and the New Age Movement, a time where people began thinking more deeply about their rights, questioning religion and spirituality and reflecting on society and their place in the world. Along with these movements came praxis with organizations creating programs such as the Black Free Breakfast Food Program, Rainbow Coalition, and the Conservative Vice Lords (CLV). The CLV eventually created a gallery Art & Soul run which opened with “The Sounds of Blackness” in 1968.17

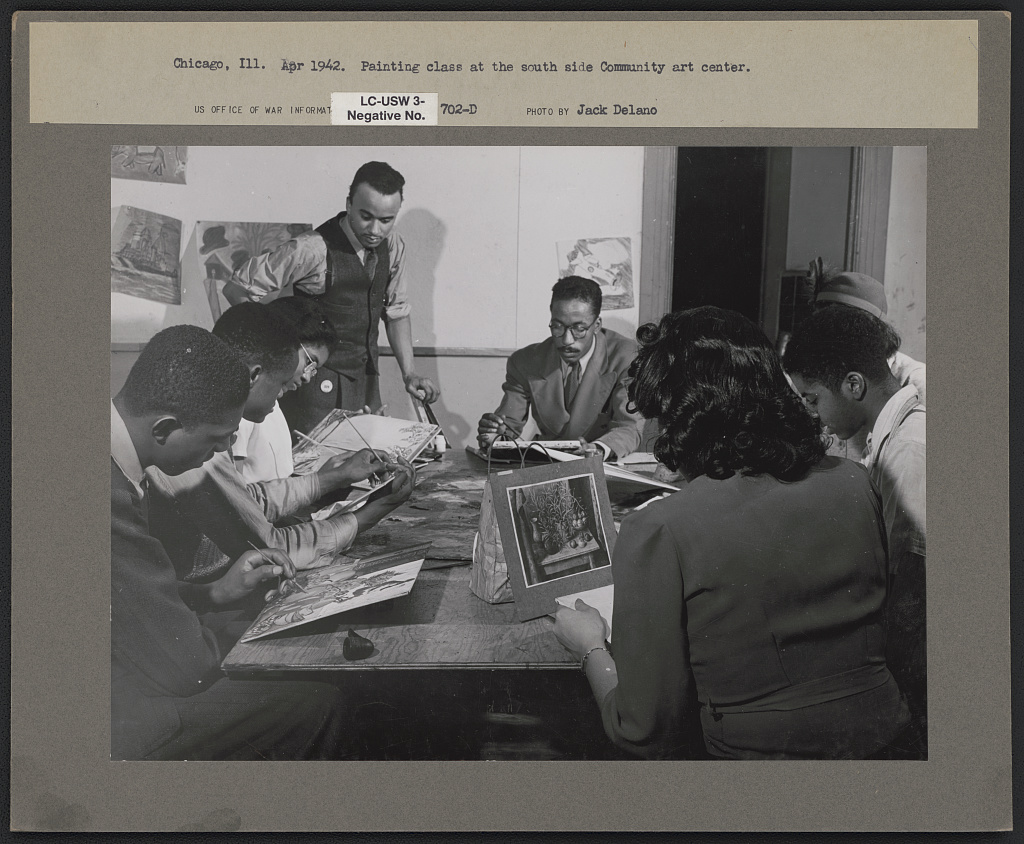

Hyde Park and South Shore became places to convene for Black Artists, thanks in part to places such as The South Side Community Art Center (SSAC) located at 3831 S. Michigan Avenue, it was host the first Black art museum—The DuSable Art Museum located at 740 East 56th Place, and it has been a hub for Black artists since around 1938.18

After finishing college and returning to Chicago after seeing art across Europe in 1968, Olu came back recognizing the growing need for a space where Black artists in Chicago could have conversations about culture, envision the future, and organize toward peace. In the early years of the Black Arts Movement, there was more of an abundance of work being made than for it to be shown in Chicago. Only a handful of galleries for Black artists were open then—Art & Soul, Zambezi Artist Guild, and Lakeside Gallery.19

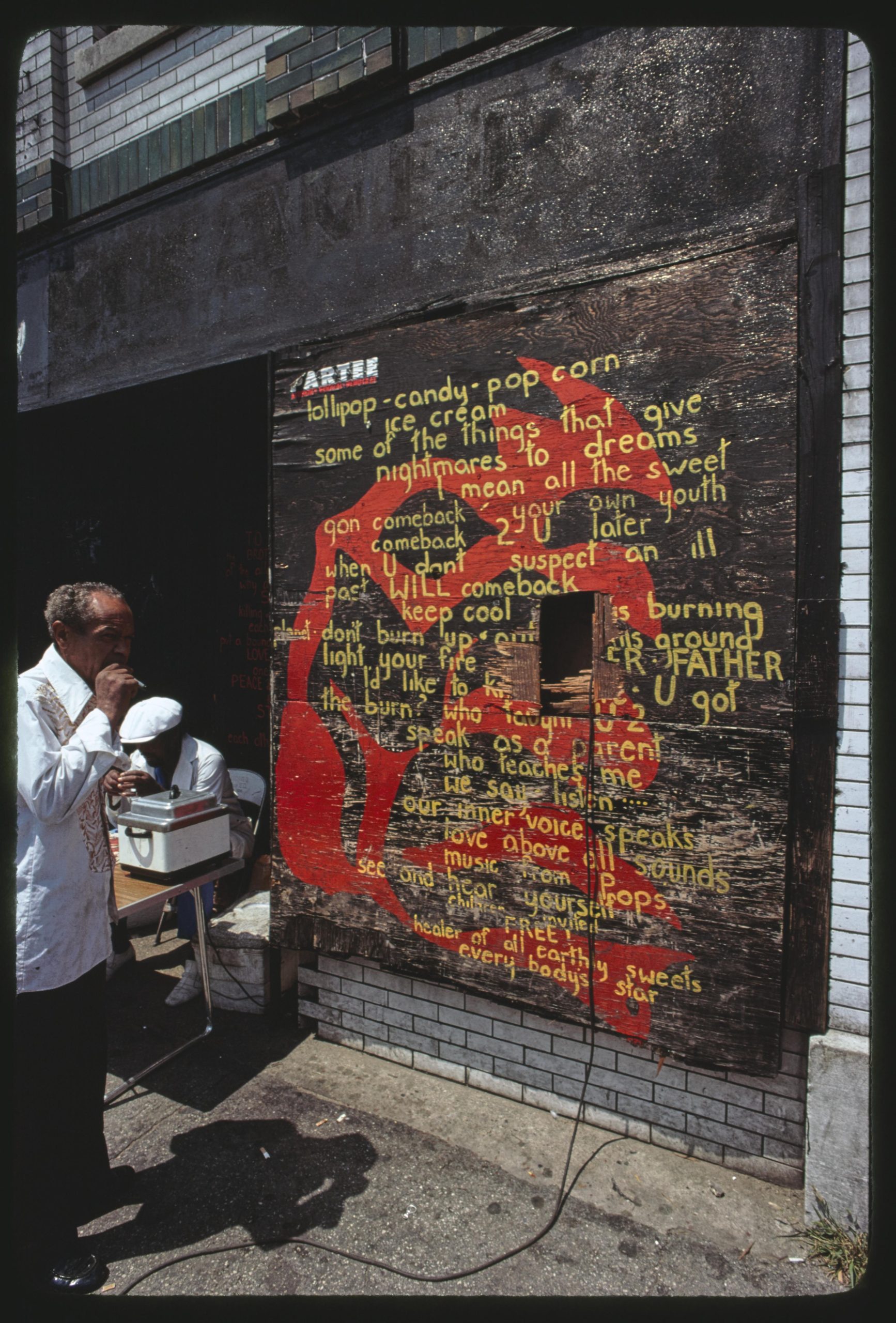

Image (left): Image: Yaoundé Olu, uniphysicist, photographed in front of Oşun Studio, 2541 E. 75th St., Chicago, Illinois. Image by Jonas Dovydenas for the Library of Congress’ Chicago Ethnic Arts Project.

Cruising through South Shore with her then-boyfriend photographer Jimmy Porter, Olu and Porter found a space for sale. Together they started East Shore Gallery. They changed the name to Oşun and opened in May, 1968 at 2541 E. 75th Street. The first staff included friends and fellow artists, including Ngozi (Sheila Hollaman/Rashid), Patricia McCombs, and Tazama Sun, all of whom started on her team and would also exhibit their works. Eventually, busy with other projects, Porter faded out of his role as collaborator and Olu took over.

Oşun is the Yoruba word for, “love, sexuality, fertility, femininity, water, destiny, divination, purity, and beauty, and the Oşun River.” Oṣun was founded because of a shortage of available exhibition space for African American artists, especially those who had not yet become known in mainstream venues.20 They also thought an arts facility would help create a stronger community.

Oşun began as a vehicle to promote emerging Black artists and in time it also became a community arts, events and discussion space. These events were timely, and in conversation with the various creative and political movements which touched the South Shore community at the time, such as The Woman’s Rights Movement, New Age Movement and The Black Art Movement, and/or opportunities to discuss local issues and dreams for improving the neighborhood with its residents. Her first collaborators at the gallery were her close friends and the Oşun’s circle eventually expanded to include others who were drawn to the space and the ideas being exchanged there. Over the years the gallery gained notoriety far beyond Chicago with requests coming outside the United States to show their work in the space.

“It was a community space or a salon because people came to hear the music and see the art, as well as to sit and talk. It was philosophical: we talked about art, the nature of art, art for art’s sake versus art for the people’s sake. It was cultural-political in that the whole purpose for me having the gallery, outside of showcasing the works of African American artists, was to help encourage the community to rise to another level…” In that vein, she one of the events she held at Oşun was a Barter & Trade Fair: “If you have what I need and I have what you need, why do we have to have an intermediary? At that time the idea was that we could begin to look at each other as resources, and so we wouldn’t have to, you know, have any intermediaries. We can exchange, share with each other, and some good things came out of it.”

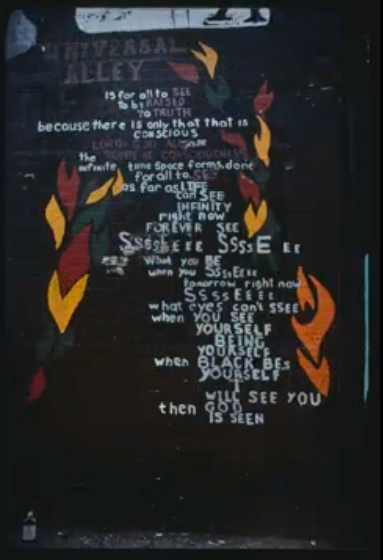

Olu mentioned, that it a quite a special space in time that Oşun ran, because the community was in a state of transition and community-based, creativity was at the center of this transition. Eventually, at least five other arts facilities along the strip between Phillips Street and Exchange on 75th Street in South Shore. Collaboration, exchange, and intrigue grew with those places as hubs in the neighborhood and surrounding areas. Over the years of the BAC, the people and projects who came through the neighborhood included the jazz spot, The Alley and its mural “The Rip-Off/Universal Alley”(1973) by Michelle Caton, Sun Ra, Phil Cochran’s 75th Street Studio, Third World Press, Lakeside Gallery, OBAC (which planned the seminal mural Wall of Respect in a space on 75th street), Obilo recording studio, the gallery of Maurice Hodo, and numerous studios such as that of Myrna Weaver and Haar-di.21

Oṣun Gallery was eventually changed to Oṣun Center for the Arts because of a change in focus to beyond fine arts. It became a venue for many other events and activities in addition to art exhibits. The strip was culturally rich, with visitors coming from all over the country.

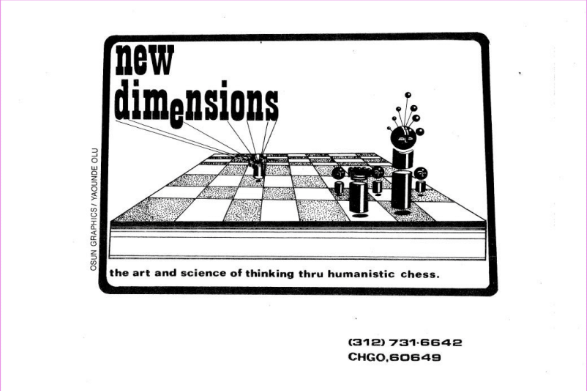

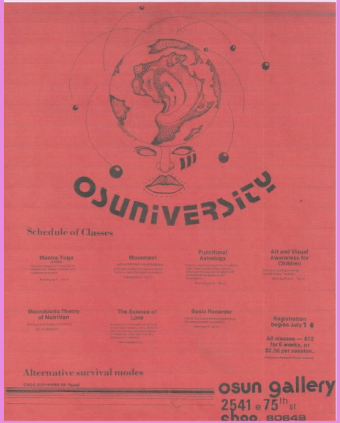

The wide range of programming and experimental initiatives at Osun included free stores, “Success Through Self Awareness” seminars, yoga classes, a hand-carved puppet show, and more. According to Olu, it’s mission was to “provide quality programs that are accessible to the community: a newsletter, a barter and trade festival, a poetry concert, experimental percussion workshops, concerts by the recently formed Association for Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), and a lecture discussion series entitled ‘Symposium on Civilization.’” There was also a subsidiary titled Oşun Graphics which provided quality illustration, layout and design services, and Oşuniversity, a series of classes that range from “The Macrobiotic Theory of Nutrition” to the “Science of Love,” as well as Oşun Publications.22

Oşun also gave artists work to help host events or promote the center. Oşun was a space for the community to gather, people of all ages including children from the neighborhood.

AFAM, East Shore ,and South Side Art Community Center, were some of the other Black art spaces operating at the same time as Oşun. These places and the people working during that time included AfriCOBRA, the AACM, poets such as Haki R. Madhubuti, muralists, photographers such as Don McIlvaine, and movements in art such as The Black Arts Movement, all of which served as motivation and inspiration in the work Olu did for Oşun, her personal artwork, and elsewhere.23

Further Comic Work and Creative Collaborations

Through Oşun, Olu quickly formed a posse of Black comic artist friends including Tim Jackson, Turtel Onli (1952-1925), and Omar Lama (1942-2022). Onli was in one of her first group shows at Oşun while he was still in high school.

Onli, though, was the comic artist she first bonded with over their similar creative ethos and love for comics. Their work often centered Black liberation politics, but it didn’t fit in with the likes of AfriCOBRA. Their work wasn’t traditional art that people might buy to hang on their walls. Onli and Olu shared similar influences such as science fiction, the work of underground comic artists, and a love of music. They were also both interested in expanding the notion of what Black Art is or can be while thinking within the context of lineage, “Why are most music collections or playlists more Black than most comic or graphic novel collections?” Onli asked in a 2014 interview.24

After seeing Onli’s work and success as a professional comic artist, Olu was motivated to collaborate, inspired to make new work, and was able to see comics as a viable way to make some income while running Oşun.

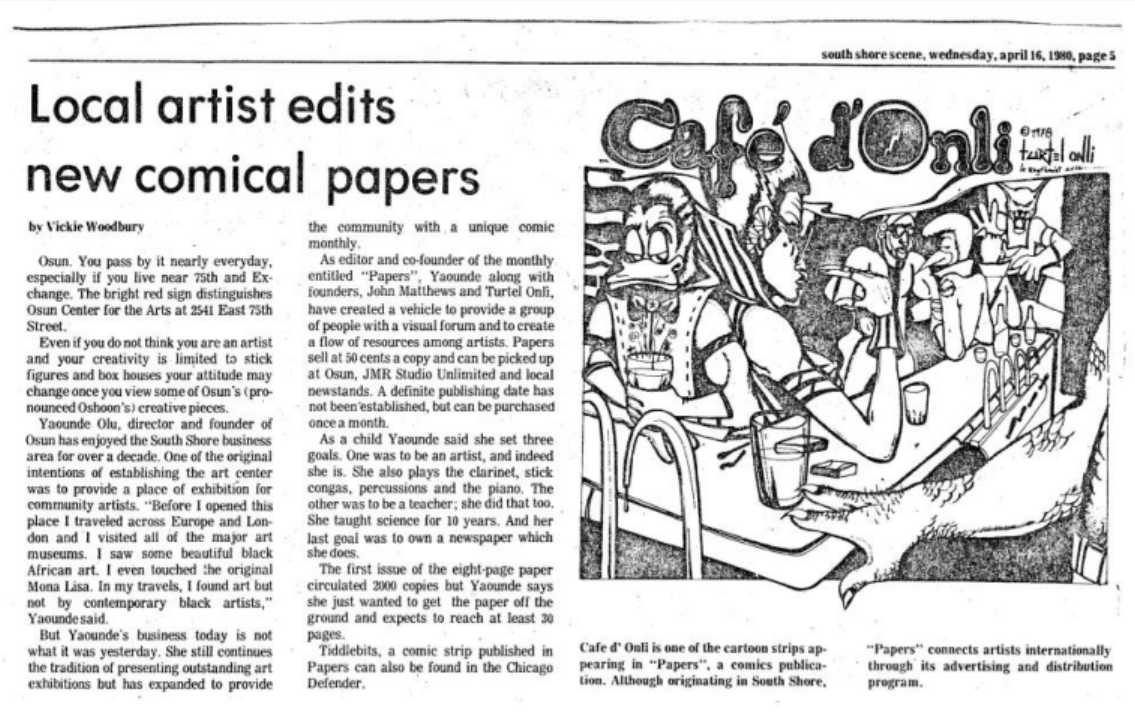

One of Olu’s early collaborations with people she met through Oşun was Papers, a community newsletter that featured Olu and her friends comics, which she made with Onli and John Matthews. Olu mentioned that “Papers sold more than 2,000 copies in its first run”—a testament to its popularity.

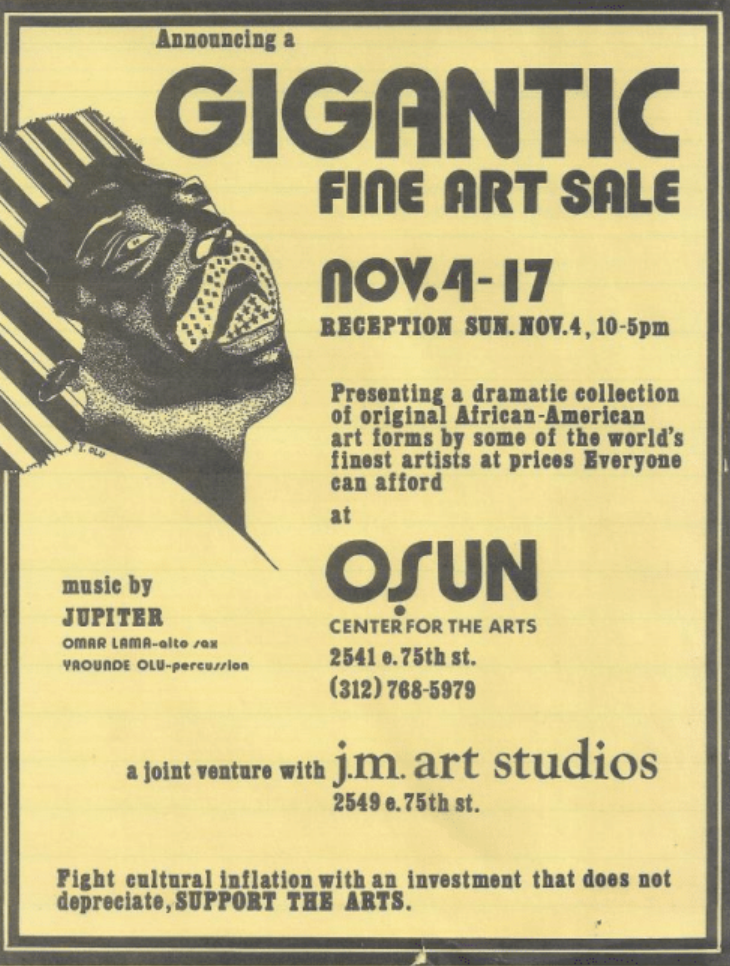

In the late 70s, a collaboration came in the form of Jupiter, a music group Olu formed with Omar Lama that evolved out of the musical events going on in and around Oşun. Olu played congas and other various instruments while Lama played saxophone.

There were few galleries for Black artists at the time. This is part of why Black artists had to diversify or unionize and collaborate to make music and create murals. For example, precocious Onli started the Black Arts Guild, which functioned financially in a socialist manner. While being a gallerist, Olu continued to work as a teacher.

On the flipside, there was an abundance of mentors for her and other Black artists, particularly socially conscious artists. She counts Bill Walker, founder of the Black arts mural movement in Chicago and creator of The Wall of Respect, an initiative of OBAC, as an extremely important influence. The Wall of Respect is considered the first large-scale, outdoor community mural and is credited with spawning a movement across the U.S. and internationally.25

Between her time as a gallerist and individual artist, under the direction of Walker, Olu assisted with a mural on 47th and Calumet, a block away from Cane Drive, which was called South Park at the time. That mural has been since demolished. What still stands is the mural across the street, Wall of Daydreaming and Man’s Inhumanity to Man, 1975, which was also led by Walker’s direction.26 It highlighted the ills that were being brought into the Black community through drugs. This mural stands as an artifact of the intentionally impactful, community-orientated art that was being made in and around South Shore during the time.

Olu was witness to the naissance of many, now storied, movements in the history of Black political art in her time including the birth of the Association for the Advancement for Creative Musicians (AACM), AfriCOBRA, The Organization of Black American Culture (OBA-C), and counts some of the members of these organizations as her friends and artistic collaborators.

She knew many famed Black artists including Gwendolyn Brooks. Olu completed a portrait of Brooks and presented it to her at the Urban League when Olu was running a youth program there. She also counts Dr. Margaret Burroughs as one of her toughest mentors: “[Burroughs] really pushed people… She really took people under her wing and encouraged them to pursue opportunities and to try to reach whatever goals they were. And she made recommendations as to the things that we should have done. For example, Burroughs was the one that thought I was made to be a college teacher—in art. And I agree with her, but for some reason, it never did happen. I was not really in total control of my corporate or not-for-profit life, basically, because once again, people came. I never had to actually go out and get a job, except the very first one, when I was teaching. I’ve just gotten jobs by people calling me and asking me to do this, do that.”

For a time, Olu worked on and exhibited her personal art while running Oşun. She continued making comics, paintings, practicing astrology, music and writing books. One of her exhibits during the time, “Galaxy Council” (1977) included painted mannequins that are made to look like the entities she often paints. The walls were done in “chocolate-covered burlap”¹⁰. Olu was interviewed by Robert Metcalfe Jr. and the work was photographed by Jonas Dovydenas as part of the Library of Congress’ Chicago Ethnic Arts Project in 1977.27 She DJ’d for WHPK’s Jazz slot, participated in the Black Esthetics festival at the Museum of Science and Industry, and practiced astrology. In 1980, she began one of her most lasting roles as the weekly comic artist for the Chicago and Gary Crusader Newspaper group (she has never missed a column to this day). For her work at The Crusader, Olu won four Wilbur L. Holloway Best Editorial Cartoon Awards.

She also has had her work published in The Chicago Defender, the longest-run Black-owned print publication in the United States.

As the gallery grew, the labor involved in keeping the gallery afloat grew and the gallery wasn’t a financially profitable project. Towards the latter half of Oşun’s existence, Olu quit showing her work outside of the gallery and spent time working as a teacher to keep up with the pace of the work and keep the gallery afloat. While not profitable, it was a labor of love that brought with it a wealth of community bonds and a space to deepen conversations around culture and politics. Olu stressed that her experience wasn’t and isn’t unique, Black artists often have had to diversify their skills in order to pay their bills and sustain their livelihoods and careers. She has been a principal, a physics teacher, a non-profit administrator in addition to being an artist before, during, and after the gallery—and most of her peers have had to do the same due to the structure of the art market and the socioeconomic factors that Black artists are often under.

When she started her gallery there were about five or six other cultural facilities including galleries and record shops. They multiplied over time, and the community was trying to keep it a flourishing space for Black culture; however, a gang took over the building across the street from Oṣun and the gallery subsequently closed in the fall of 1982 after 14 years of existence. It was no longer a safe space for Olu, children, and the flourishing Black community that had been growing on the Southside and beyond. After the closure, she still kept in touch with and collected the artists she worked with during her time as a gallerist. Although splintered, Oşun and other Black artist organizations and collectives at this time put roots in the ground for connections to still be made and maintained.

Post-Oşun Reflections

Oşun was profiled as part of the 2018 exhibition, “The Time Is Now!”—subtitled “Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side, 1960-1980″—which captured the two fervent decades during which Chicago’s Black artists made their work the vehicle for and expression of the revolutionary civil and social change they sought. The exhibition statement explains that “the title also speaks to a more generally held feeling of urgency in art of the time, to the concern that art be timely”.28

The exhibition documented South Side institutions that were open at the same time as Oşun, “from the Alley to the South Side Community Art Center and—across the street from it—Margaret Burroughs’s home museum that became the DuSable. It chronicles artist collectives (OBAC, the Organization of Black African Culture; AfriCOBRA, the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), the origins of the mural movement, and the shift from the civil rights era to the era of black power”.29

The Time is Now! also catalogues the concerted displacement of African-Americans living on the South Side by institutions such as the University of Chicago through their mid-20th-century urban renewal campaign (also known as the “Negro removal”).30 The problems South Side artists were grappling with between 1960-1980, the same issues that led to Oşun’s closure, are still affecting these neighborhoods today. Empty lots and abandoned buildings are purchased by people outside the neighborhood and left to deteriorate until a wealthier developer pays to build housing or business unaffordable to current residents.

Olu believes the landscape for Black artists has changed since the urban renewal campaign and since Oşun had to close its doors, but there is still an issue of tokenism in the sense that certain narratives and kinds of arts get pushed to the point of stereotyping; however, she also recognizes there is a more robust community of collectors interested in the work of Black artists, cultivated in part by organizations such as Diasporal Rhythms, which according their statement on their site,” is an organization whose mission is to promote, preserve, and pair work with Black artists with collectors”, who she has worked with in the past on building her collection.31

Other Work, Abridged

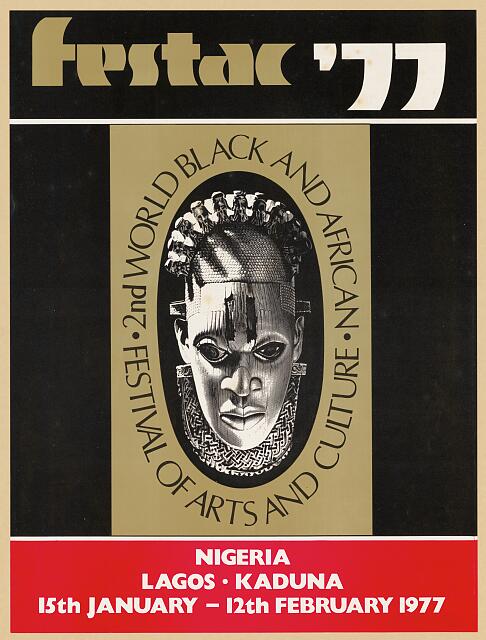

Black arts advocate, FESTAC ’77 African-American Culture Representative

Olu also held administrative titles for various organizations such as The Safer Foundation and Black Artist Celebration and the South Side Community Art Center in Bronzeville, the oldest African American art center in the United States, where she was a long-time board member.

In 1977, Olu was made a United States representative for FESTAC ‘77, also known as the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture held in Lagos, Nigeria. She also spent a lot of time with the Afrofuturist musician Sun Ra during that event. She remembers how welcoming native-born Africans were to her as a United States born citizen of African descent. She also said the experience made her realize that there is a cross cultural tendency for Africans to have a tribal mindset when it comes to traditions and breaking them. When Sun Ra performed, the audience heckled Sun Ra and left. Yaoundé Olu was one of a handful who stayed to listen to the full set. Sun Ra played on despite the disruption.

Along with some of the earliest comic friends and collaborators, including Onli, Olu was included in the 2022 MCA Chicago show “Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now” and its companion book titled “It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940-1980”.32 The catalogue was a first-of-its-kind anthology of Black comic artists in Chicago. The exhibition also wove together Black artists across a range of generations, revealing the multiplicity of voices responsible for shaping comic’s history as a site of expression of Black culture as well as resistance to inequity.33

The exhibition traced the evolution of six decades of comics in Chicago, as cartoonists ventured beyond the pages of newspapers and into experimental territory including long-form storytelling, countercultural critique, and political activism. The exhibition sought to bring to the fore artists of color who were previously under-recognized throughout their careers. Getting more recognition for Black comics in Chicago and elsewhere was one of the main goals for Olu’s close friend and collaborator, Turtel Onli.⁵ He underwrote a Black Age Comics Festival held at South Side Art Center for over 30 years beginning in 1993.⁶ It was also a goal of Olu’s close friend Tim Jackson (1958-2024), who wrote the book “Pioneering Cartoonists of Color” (2017), which features a profile on Olu.

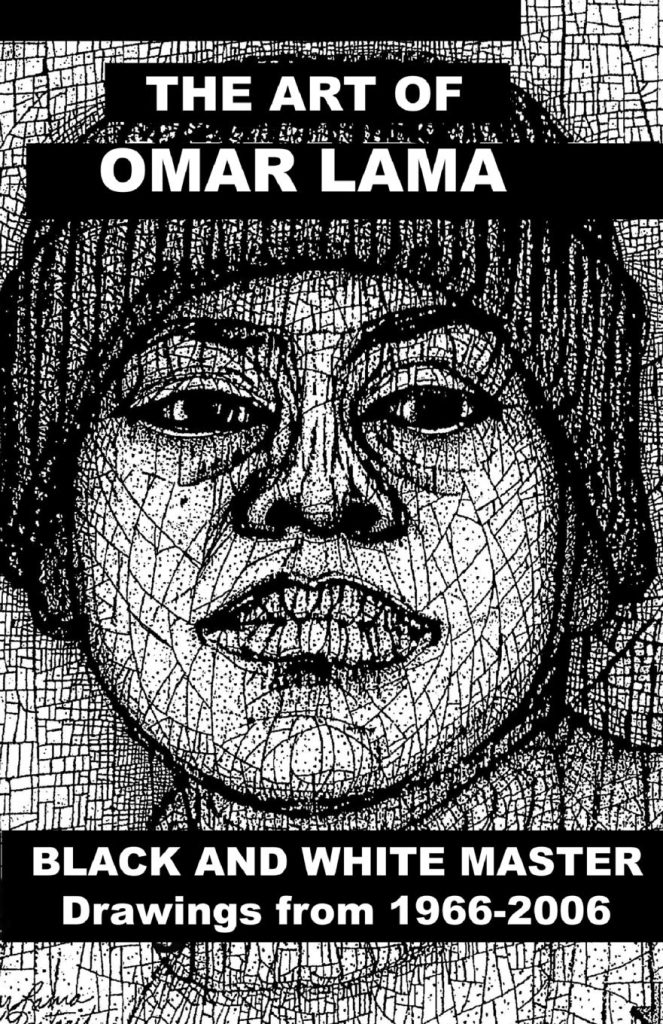

Always one to mentor and uplift artists, Olu has also worked in youth arts non-for-profits, and designed, edited, and published a book showcasing the work of her early Oşun contributing artist, Omar Lama (1942-2022), titled “Black and White Master: Drawings by Omar Lama”(2014).

Drum Divas

For years, beginning in the early 1970s, Olu would go with her friends to a summer retreat in Michigan that would have drum circles. This was during a time when there was often push back from men when a woman wanted to participate in drumming. The usual pejorative used at the time was that “a woman shouldn’t have anything between her legs,” Olu said. This didn’t stop her and her affinity towards drums.

Olu makes music both as a solo artist and as a founder and member of the group, Drum Divas, which was formed in 2003. The name “Drum Divas” came to Olu in the night, right before they were solidifying their group. During Drum Divas first official show they were upstaged by a group called The Bucket Boys—a band of brothers who drum on plastic bucks—in one of their first gigs. Following this experience, Olu realized the importance of practice. The lineup in Drum Divas is open and ever changing, only six of the original Drum Divas’ drummers remain. The group’s sound is influenced by tribal rhythms across Africa, and the world of artists in other disciplines such as Katherine Dunham as well as contemporary genres of music. Their specialty is that of creating original drum songs. The Drum Divas seldom advertise and perform upon invitation to spaces around the city including The Chicago Cultural Center and Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Sapphires & Crystals

In line with a major theme throughout her life, one of supportive and lasting friendships, Olu is a member of Sapphire & Crystals, a collective of African American women artists in Chicago. Formed in 1987 by artists Felicia Grant Preston and Marva Pitchford Jolly (1937-2012), who was a friend of Olu’s from her MFA program, the group was formed after Barbara Jones-Hogu’s curated at SSAC, titled Fem-Images in Black, which featured all Black women artists and the discussions that followed after the dissolution of Pitchford-Jolly and Felicia’s ceramics group, Mud People’s Black Women’s Resource Sharing Workshop, in 1986.34 Prior to forming of the organization there wasn’t a coalition in Chicago that would deal with the intersections between issues of sexism and racism in the fine arts. For example, according to both Olu and the Chicagoan-artist Robert Paige (1938-), SSAC only began to feature more women artists after realizing they had not had any one or two person shows featuring all women artists (except for Barbara Jones-Hogu’s show) at the gallery prior to 1973.35 Olu herself participated in one of those first two-person shows at SSAC in September 1973 with Douglas Williams. According to Olu, this noticing of the gap was a trend by SSAC and other galleries during the Women’s Right’s Movement in the 1970s. There were efforts by other galleries like that of SSAC to include women in the context of the Women’s Rights Movement as it was part of the contemporary moment, but Olu said, by the time that wave had passed, her and her fellow Black women artist colleagues noticed the shift back to business as usual: institutional occlusion of Black women in fine arts. By the time Sapphire & Crystals formed in 1987 there were still a lot of gaps in equity for Black women in fine arts, so the collective was created with the intent to form a network of support for Black women artists and to provide opportunities for them to exhibit their work, much like Mud People’s, but with the intention of further longevity. The collective name was inspired by the hardiness and beauty of the sapphire’ gemstone and connotation of the word sapphire, with the “Sapphire” stereotype, also known as “the angry black woman” trope, as a way to negative pit the meaning of sapphire against positive meanings in the context of Black Womanhood. The oppressive ‘Sapphire’ meaning is pitted against the spiritual properties of sapphires and crystals. According to member Rose Blouin, “it stands for empowered woman who stood up for herself and crafted her own destiny, ideas which were consonant with our objective.” Since their first show in 1987, Sapphires & Crystals has grown to over 40 members who have shown both nationally and internationally. While each member has different methods and mediums in which they approach their work, consistent topics throughout their history include critical analysis of race and gender and honoring their ancestry.

Current Studio Practice

Olu currently has a studio at Bridgeport Art Center (BAC). The space, which she’s worked out of for more than a decade, functions as a showroom, a place to meet clients, and as a creative work space. She makes most of her work in her home, which sometimes makes creating larger work difficult. When she joined BAC she was one of only a few Black artists at the time, but over the years she says there has been a shift and other Black artists, including some of her closest and long time friends like fellow Sapphire and Crystals member Patricia Stewart, have begun to rent studios in the space. In addition to being an artist at BAC, Olu has curated a couple of their exhibitions, including their 9th Annual Juried Art Competition, which she also served as a judge for.

Olu says the core themes and style of her work hasn’t changed since the beginning, but she has changed or added mediums over the years. For example, she used to mostly paint with oil or UV print, but began incorporating digital elements into her work in the early 2000s by reworking them in various experimental modalities.

She has also embraced the internet as a platform to share her work. She has a Youtube channel (bioastrix1) with videos dating back to 2009, which showcases a plethora of her music, paintings, and videos. Some of the work on the site includes, “Art” (2011), which consists of a slideshow of her work and uses Olu’s own song “Transformation” as a soundtrack, and “Plumpetta’s Palace”(2010), which consists of two AI-voiceover Lego characters engaged in a philosophical conversation on what it means to be a good person.36 Each of the works on the channel nods to Olu’s characteristic Retrofuturist style, interest in physics, astrology, and philosophical humor.

Olu’s Reflections on the Art World Today

She says sometimes people seem perplexed with her work, particularly whatever her newest work happens to be. The oldest ones seem to get sold as fresh ideas need time to marinate before being accepted, understood, and attuned to by an audience.

Regarding this, Olu says, “I read somewhere that it takes 40 or 50 years before something matures, you know, if it’s different and people don’t like it, or if it’s strange, then it will take time for people to warm up to the concept. That is the story of my life. Because now I’m at a point where I can get sales unlike anything that I could get in previous years. […]the work that I did many, many years ago, that’s the work people like the best. The stuff that I just started doing, people don’t tell me they hate it or whatever, but they’re tentative. […] I don’t think this is particular just to me. I believe that there’s an incubation period that happens with artists a lot of times. And I think that’s why they always talk about the artist. You won’t get to become famous until you die. Did you know Barbara Jones? Now her work is big money, a big money draw right now, this very moment. But not when she was living. So there’s something about art and people where they want things to marinate, something before it’s, you know, before it’s appreciated or accepted or to create a mythology around the thing that makes it feel more sellable. I feel like that is the public. And I think that also might’ve been part of it, but sort of mythologizing that time and bringing that back to the public might also be more money for the market.”

On Creating an Artistic Legacy

But maybe part of the work of an artist is creating a narrative? To that, Olu says. “Yeah…‘it’s meant to be.’ Well, I don’t like that idea. So, I’ve learned that [artists] have to be true to [themselves]. I have to be true to myself. I don’t think [early recognition] is super important because what happens is that as time passes, people become used to what you’re doing, if you’re able to communicate it. And if you’re unique enough, people will pay attention.” There’s a real reward to moving to the beat of one’s own drum.

List of Events and People related to Oşun Center for the Arts:

Events, included, but are not limited to:

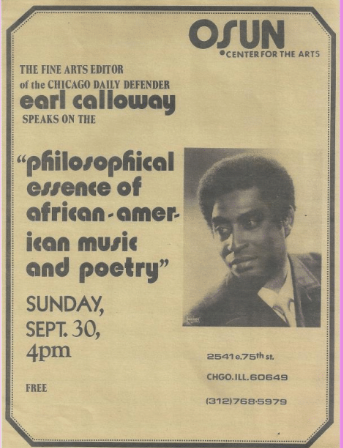

Earl Calloway–Chicago Defender, Cultural Arts Editor Presentation

Kelan Phil Cohran Cultural And Blackness Series With Darlene Blackburn Dancers

Literary Exchange–Book Discussion/event barter And Trade Fair

Oṣuniversity African Puppet Show Featuring Hand-carved Puppets by Alabi Ayinla

Success For Self-awareness Seminars Presented By Johnnie Haygood

Fashion Auction Presented By Bare Essentials

Poet Rhonda Davis

Yoga Classes Taught By Becky Love And William Green Festival of The Arts

Intaking Art To The Community

Guys And Dolls Lounge

Henry Threadgill’s Performance Piece Hymn To The Sky

Special Partnerships: Jimmy Porter Photographer: Sheila Ngozi Rashid-Jewelry Designer: Tazama Sun–Leather Craftsman: Patricia Mccombs Macrame’ Hanging Series: Donna Todd

Visual Artists included, but not limited to: Randson C. Boykin, Walter Bradford, Okolo Ewuni, Keodu Oqueri, Ikechi Lawrence Kennon, Esq. Johnnie Matthews, Ralph H. Metcalfe Jr., Johnny Matthews, Turtel Onli, Espi Eph, Kenneth Hunter Jim Smoot, Omar Lama, Lester Lashley, Dale Spann, Tom Range, Ben Bey, Wesley Tyus, Tazama Sunkush Bey, Donnie Carter, Carol James, Max Fran Smith, Pat Mccombs Edfu Kinginga, Ray Gipson, Eileen Abdul Rashid, Paul Osifo, Peter Barge, Joseph Dudley, Jackie Wright, Kwaku House, Dalton Brown, Ira Neubel, Alicia Griffin, Dale Normand, and others.

Musicians included, but not limited to: AACM (Association For The Advancement Of Creative Musicians (Most Members) Muhal Richard Abrams Amina Claudine Myers Roscoe Mitchell Pete Cosey Lester Lashley Jose’ Williams Soji Adebayosura Ramsesafga Salon (W/Larry Dunn Charles Wes Cochran And The Spirithenry Threadgill, Abdul Sami and The Piece Of Time Band, Steve Mccall, Fred Hopkins, Joseph Jarman

Light: Henry Huff, Malachi Favors, Maghostuthana, Jon Taylor, Edward Wilkerson (Eight Bold Souls), Naomi Millender, Ernest Khabeer Dawkins, Imhotep Ba’s Sunship, Khusenaton An The Golden Circleaye Atonkalaparusha and The Light, Enochben Montgomery, Mchaka Uba

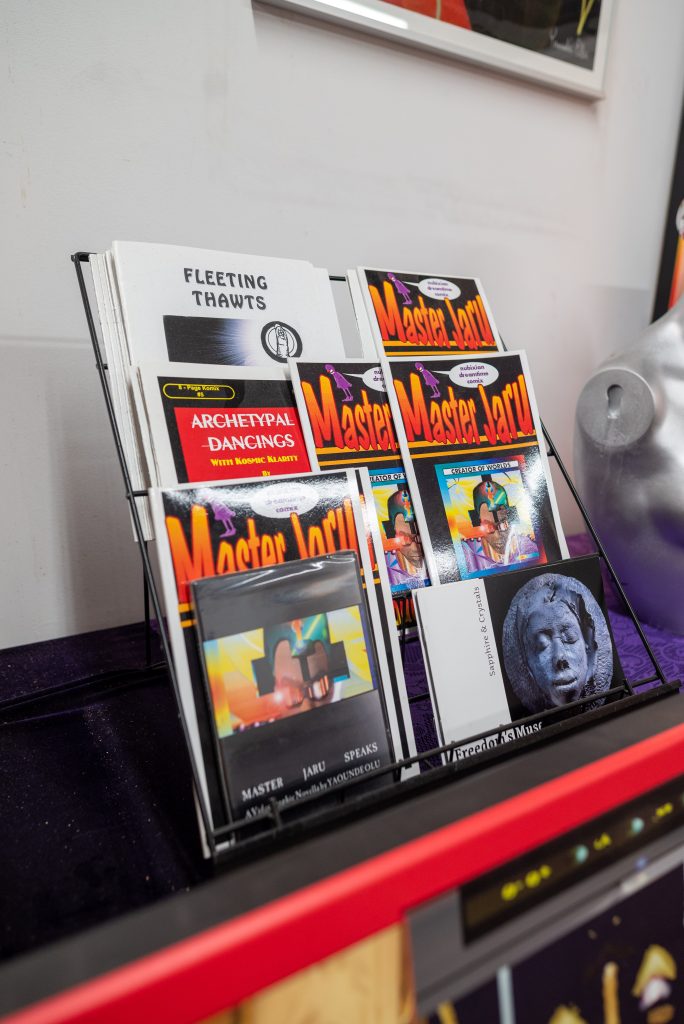

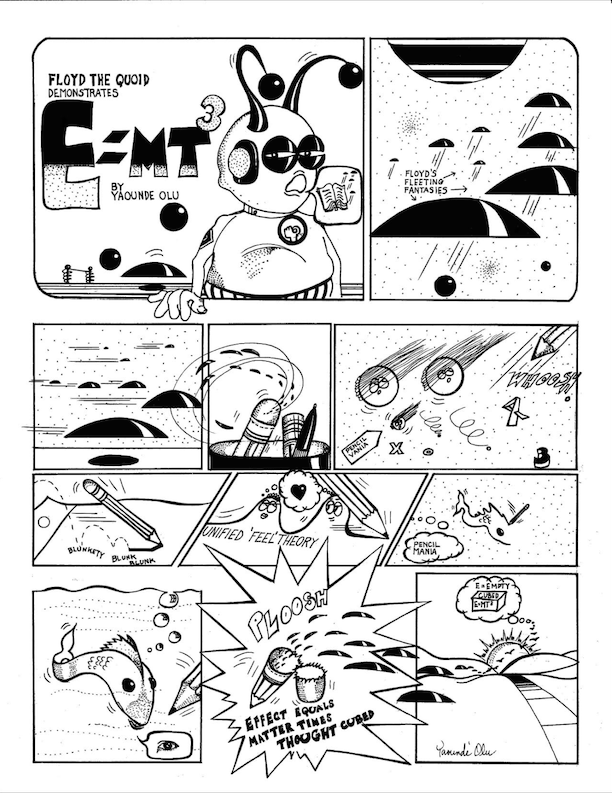

Olu’s Non-editorial Comic + Book Catalogue Includes, but is not limited to the following:

– A series of Cosmic Comics philosophical science fiction comics, videographic novellas and prints.

– The Ebixian Chronices includes “the transformation of Threee “ the first of the series wherein the character, Three, comes to terms with the part that he played in the fall of that civilization.

– The Archetypal Dancings “The second 8-page vignette takes place after the migration and destruction of Ebixia. It also provides a glimpse of life before the crisis.

– Ebixia: A Proto-history – Escape Toward Destiny: the third in the series of 8 – page vignettes captures a glance of the conditions that existed just after the great migration, which became necessary because of an abuse of life codes.”

– New Ebixia “a graphic novel depicting charcteristics of the new home that they found in a non-binary civilization free from war and chaos where they start anew.”

– Jabulu: Message from a Hydrogen God “non-traditional ideas about life and living offered by Jabulu from the Hydrogen Constellation.

– Master Jaru: Creator of Worlds “Nubixian Master from a type 7 civilization who has mastered the art and science of life offers advice about how to move from a lower type civilization to a higher one, as well as sharing information about how to navigate the moving synchronicity path known as the holomovement.”

– Dream Slayers “advice on how to battle Aaroth Dream Slayers who want to keep you from succeeding in life.”

– Slinky Ledbetter & Comp’ny “new type of super heroes from inner space in the Constellation of Benzene.”

– Fleeting Thawts “whimsical travels in life and morphing thought to the mind of the recipient of the thought.”

– Missy Foo Foo’s Finger Tips “sage advice from Missy Foo Foo, plus a Perpetual Calendar.”

Videographic Novellas

– Meme 27 “an admonition from Meme 27 about how to avoid being influenced by propaganda. Soundtrack by DJ Yaya.

– Master Jaru: Master of Worlds“offers advice about how to move from a lower type civilization to a higher one, as well as information about how to navigate the moving synchronicity path known as the holomovement. Soundtrack by Kahil ‘El Zabar’s Ethnic Heritage Ensemble.”

Each of these works infuse her characteristic “Retro-futurist” style and philosophical pondering and her threads of her various interests and proclivities particularly physics and humor. You can find many of these comics available for download on her Scribd, bioastronomy1.

Interested in viewing more of Olu’s work?

- You Can Find Olu’s Paintings And Prints For Sale and View Online

- Her Youtube channel

- Drum Divas online catalogue

You can also visit her at her studio by booking an appt. through Bridgeport Art Center or stopping by the Art Center on their third Friday’s open studios event.

Works Cited

- City of Chicago. (2025). (rep.). Englewood Community Data Snapshot Chicago Community Area Series July 2025 Release (pp. 1–17). ↩︎

- The University of Chicago. (2007). Housing. https://southside.uchicago.edu/History/Housing.html ↩︎

- City of Chicago. (2025). (rep.). Englewood Community Data Snapshot Chicago Community Area Series July 2025 Release (pp. 1–17). ↩︎

- “Remembering the Chicago Defender, Print Edition (1905 – 2019) | National Museum of African American History and Culture.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian, 2019, nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/remembering-chicago-defender-print-edition-1905-2019. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Jack and Jill. “Teen Town Chatter.” Historical Newspapers from 1700s-2000s – Newspapers.Com, The Chicago Defender, 29 Sept. 1962, www.newspapers.com/image/1139741326/?match=1&terms=defender+younger+set+central+utopian+players+joyce.+beatrice+watson.Chicago, IL. ↩︎

- Bowen, J. (1965, August 8). Samuel Aikens Note of Hate Gets Retort. Chicago Defender. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://www.newspapers.com/image/1135899680/?match=1&terms=chicago%20joyce%20bowen%20samuel%20aikens. ↩︎

- BOWEN, JOYCE P. Unimath: Hidden Supersymmetry in All Number Sequences. EISENBRAUNS, 2012.

↩︎ - Olu, Yaounde. “Black Field / White Field.” BLACK FIELD / WHITE FIELD , Evanston Art Center, 2002, www.evanstonartcenter.org/exhibitions/black-field-white-field. Yaounde Olu’s artist statement. ↩︎

- Dery, Mark (1993). “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose”. The South Atlantic Quarterly. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press: 736. OCLC 30482743l ↩︎

- Yussuf, Aurella Yussuf, et al. “But How Do We Get There? A Roundtable on Afrofuturism – Seen.” BlackStar , 6 Mar. 2023, www.blackstarfest.org/seen/read/issue005/a-roundtable-on-afrofuturism/. ↩︎

- The Time is Now! Celebrates the Black Artists of the South Side Who Used Their Work as a Vehicle for Social Change. Chicago Reader. https://chicagoreader.com/arts-culture/the-time-is-now-celebrates-the-black-artists-of-the-south-side-who-used-their-work-as-a-vehicle-for-social-change ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. (pp. 53, 102-103) ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. (pp. 126-131) ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. (pp. 39-45) ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. (pp. 53-55) ↩︎

- Olu, Y. (n.d.). A Space in Time: Osun Center for the Arts. Black the the Future Revised. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/xrk0kxr0vwubnswezgaa9/BLACK-TO-THE-FUTURE-REVISED-Copy.pptx?rlkey=h7l43z7rosp2c4j179cx4j5q8&e=9&st=888sngf7&dl=0 (pp. 1-3) ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. ↩︎

- Olu, Y. (n.d.). A Space in Time: Osun Center for the Arts. Black the the Future Revised. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/xrk0kxr0vwubnswezgaa9/BLACK-TO-THE-FUTURE-REVISED-Copy.pptx?rlkey=h7l43z7rosp2c4j179cx4j5q8&e=9&st=888sngf7&dl=0

↩︎ - Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. ↩︎

- Zorach, R., & Onli, T. (2012). Turtel Onli | Never The Same. Never the Same. other. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://never-the-same.org/interviews/turtel-onli/. ↩︎

- Alkalimat, Abdul, et al. The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago. Northwestern University Press, 2017. ↩︎

- Koenig , W. (n.d.). Wall of daydreaming and man’s inhumanity to man. Wall of Daydreaming and Man’s Inhumanity to Man. https://chicagopublicart.blogspot.com/2013/09/wall-of-daydreaming-and-mans-inhumanity.html ↩︎

- Metcalfe, R. H. & Dovydenas, J. (1977) Yaoundé Olu, uniphysicist, at her Osun Studio,E. 75th St., Chicago, Illinois. Chicago Illinois, 1977. Chicago, Illinois. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/afc1981004.094/.

↩︎ - University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art. (2017). The Time Is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side, 1960–1980. The Time Is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side, 1960–1980 | Smart Museum of Art. https://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu/exhibitions/the-time-is-now-art-worlds-of-chicagos-south-side/Olu, Y. (n.d.). A Space in Time: Osun Center for the Arts. Black the the Future Revised. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/xrk0kxr0vwubnswezgaa9/BLACK-TO-THE-FUTURE-REVISED-Copy.pptx?rlkey=h7l43z7rosp2c4j179cx4j5q8&e=9&st=888sngf7&dl=0 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Nadel, D., Schneider, J., & Darl, M. (2021). Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now. Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. https://mcachicago.org/exhibitions/2021/chicago-comics-1960s-to-now ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Hazel, T. (2022, August 5). The Vessels That Marva Made: an Interview with Members of Sapphire & Crystals. Sixty Inches From Center. https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/the-vessels-that-marva-made-an-interview-with-members-of-sapphire-crystals/ ↩︎

- Zorach, R. (2019). Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965-1975. Duke University Press (pp. 54). ↩︎

- Olu, Y. (2009, February 19). Yaoundé Olu’s Youtube Channel: bioastrix1. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/@bioastrix1 ↩︎

Black Lunch Table (BLT) is a radical archiving project. Their mission is to build a more complete understanding of cultural history by illuminating the stories of Black people and our shared stake in the world. They envision a future in which all of our histories are recorded and valued.

About the author: Nadia John (they/them) is an experimental poet and member of Sixty’s editorial staff and lead Sixty Lit. They are also an archive and exhibitions co-lead at Comfort Station in Logan Square. Their most recent published work is called Long Form which was published via Hiding Press. Their work is often motivated by their interests in narratology, psycholinguistics, musicology, art history, artistic collaboration, non-hierarchical structure, experimentalism, archives and anarchism.

About the photographer: Tonal (tuh-nawl) (they/them), is a bi-racial Black non-binary Photographer from the Midwestern city of Kalamazoo, MI, where tall grass and even taller trees first nurtured their creative spirit. Currently based in the vibrant city of Chicago, IL, Tonal’s artistic journey is a testament to the power of self-discovery and passionate exploration through community. Inspired by the authenticity of Chicago’s Black Queer art scene, their artistry is a symphony of colors, emotions, and storytelling, as they skillfully weave vibrant and authentic narratives of Black and Brown 2SLGBTQIA+ communities. Their portrait work invites viewers to pause and witness the fullness of Black and Brown queer personhood in bloom.