Tuning Away from Mechanized Listening features Midwest’s music ecosystems—listening cultures where thoughtful curation, collective engagement, and storytelling still shape what and how we hear. This series is meant to be a reminder: listening can be more than a passive, prescriptive experience.

Interviews with the members and leadership of Sound Ecology were conducted by the author in late June and early July of 2025, both in person and over the phone.

When multi-instrumentalist and composer Rob Funkhouser thinks back to 2019, he saw the Indianapolis DIY music scene “coming online,” with experimental shows attracting surprisingly large, energized crowds. He was building a significant audience for his electronic and percussion shows. Sometimes almost two hundred people packed into Healer, a punk venue housed in a repurposed office suite in a south side strip mall. All of the compositions were original, all the energy was real. The momentum was building. There was an audience for this sort of thing, Rob was certain, because he was part of that audience. The first time he saw a show like the one he put on–an experimental percussion ensemble playing in a small venue called the Joyful Noise space–was back in 2014. In the audience of that show, he thought to himself, “Oh, I’ve found my people.”

Around the same time Rob was performing underground shows, Luke Garrigus and Carly Sage were both starting their masters in music composition at Butler University. They learned under the tutelage of professors Michael Schelle and Frank Felice, friends and mentors of Rob as well, though their paths wouldn’t cross until well after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic had passed, nor would the other disparate forces that enabled the creation and success of Sound Ecologies.

Sound Ecologies is an arts organization driven by a mission of social change. A registered 501(c)3 non-profit, it employs local musicians and composers alike for performances of chamber and orchestra music, often in collaboration with other Indianapolis organizations or artists. They don’t charge entrance fees for concerts, pay all their musicians, and are largely sustained by donations and grants.

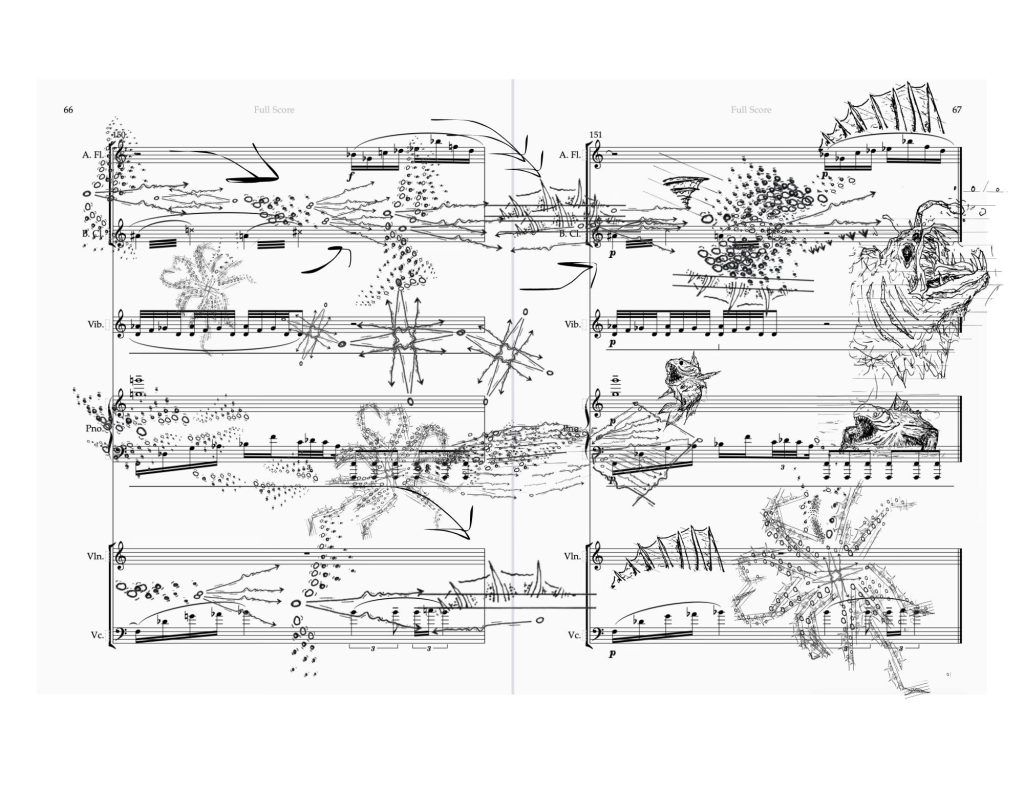

At their June 3rd Chamber Orchestra performance, held at the Ruth Lilly Performance Hall at the University of Indianapolis, Rob spoke ahead of the performance of his original work, “A Stressful Way to Relax.” Sound Ecologies, he said, is a place where musicians who leave college and don’t necessarily go on the traditional paths of full-time teaching or playing in an orchestra can still have performance opportunities. And composers who have never been paid for any of their creations before can have their works performed, an opportunity too few young composers get. The piece after Rob’s was called “Mittens, Destroyer of Worlds” and was the first live performance of a work by a twenty-year-old student composer. One would hazard to think of any opportunity an undergraduate would get to have their composition performed by a real orchestra.

I asked Rob if he ever faces any incredulity when telling people that he works as a composer for a living, and he said that it’s other classical musicians, not outsiders to the industry, who are in disbelief. “They hear what we’ve done with Sound Ecologies and think it’s not possible.”

True, it doesn’t seem possible that a volunteer organization could hold ten concerts and commission nearly one hundred original compositions per year. Nor does it seem possible that all those musicians and composers could be paid in anything but exposure, especially working in the field of contemporary classical music. But this is the mission that Luke Garrigus, Brenna Green, Logan Purcell, and the other founders of Sound Ecologies were motivated by when the idea was nascent and seemed as impossible as it sounds to someone from an established classical music institution.

In the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, Luke and Charissa Garrigus felt an opportunity gap in Indianapolis for performers and composers. They’d spent their formative years in undergrad at the University of Indianapolis having jam sessions with friends. Even with the interruption of the pandemic— and with other local ensembles like Forward Motion and the Ronen Chamber Ensemble performing and beginning to strengthen their presence in the city—there was still a dearth of opportunities for young performers and composers to experiment in the classical world.

But then they graduated from college and needed to make money. Charissa, who got a degree music education with a focus on piano, became a music teacher and performed at concert gigs on the side as Luke commenced his graduate program. Life became what a lot of people envision as the start and finish of a non-world-famous musician’s career. Following his graduation from Butler after the pandemic, Luke took up a job as a music director at University Heights United Methodist Church. Respectable and sustainable, but not as creatively fulfilling. They wanted to invest in the possibility of recapturing the joyful feeling of getting together with friends and playing work made for each other.

Luke and Charissa sat at the difficult intersection between the desire to nurture a passion and the need to legitimize it somehow. Luke had a Master’s of Fine Arts in Composition, but few opportunities to have his work premiered; Charissa hadn’t been able to perform nearly as much as she wanted to, and many of their other musician friends were facing the same struggles. These are the questions that so many young artists face in a society that does not support creatives outside of the formal institutions. Ultimately, they decided to make their own path and create something for their community.

With the help of their parents and friends, Sound Ecologies incorporated as a nonprofit organization and began its early efforts of commissioning and performing, having a goal of paying their talent starting from day one. The name comes from both their nonprofit mission of having music both represent and drive social change, often around environmental topics, but also the creation of a rich, natural environment of music.

“Sound can also mean ‘stable,’ or ‘of good quality,’” Luke explained.

Since day one, it has been run entirely by a volunteer board, with most administration being handled out of coffee shops with nothing but a laptop, a phone, and a network of support. Luke described his time spent between Sound Ecologies and his role at University Heights United Methodist Church as “two 30-hour per week jobs.” Most of their early funds came from donations and their resources from favors.

Leveraging relationships with friends and friends-of-friends from around the city, Sound Ecologies was able to find performance spaces and musicians outside their immediate friend groups looking for more opportunities to perform, as well as composers in search of an audience. As they organized, expanding their roster of talent and partnerships, they were able to develop a full-on chamber orchestra with over forty members.

Their chamber orchestra concert in the winter of 2022 was the first performance Rob Funkhouser assisted with. As a sound engineer, he helped to set up recording equipment in the northside church so that the entire concert could be recorded. That was the moment, Rob said, where he bought into the vision.

“It’s not often you meet people in this space who want to make the pie bigger.” In fact, he finds Sound Ecologies, for which he is now an artistic director, to be “extremely idealistic.” But as a lifelong optimist, that’s the kind of world he wants to live in.

Rob has been a resident artist at another southside organization that supports local artists called Big Car Collaborative. Back in the late 2010s, they bought a block of vacant homes, created a long-term co-op agreement, and, in a deliberate move against gentrification, turned the lot into an Artists and Public Life Residency Program. This program allows artists to live in these homes with a rent that is, on average, 35-50 percent below market rate, enabling artmaking with fewer financial restraints. After years of hobbled-together part-time jobs and gigs, Rob has been able to fully transition to freelance work in sound-mixing, teaching, composing, and performing, in large part thanks to Big Car’s vision.

It’s also thanks to Rob that Sound Ecologies is able to successfully carry out one of their most incredible initiatives in support of their composers, which is recording performances and giving the composers rights to those masters. As composers, having rights to those recordings and receiving royalties for them is an invaluable career milestone.

I was in attendance at that winter 2022 concert, as well as a classical musician friend of mine, Hunter Wheatcraft. We found Sound Ecologies the way many people do, through friends of friends. It was this performance that got Hunter interested in joining the organization.

Hunter, a classical percussionist who performs with the chamber orchestra, is a teacher and used to bartend on the side. He is like many of the performers in the Sound Ecologies ensembles–working multiple music-related jobs and constantly in search of new and more exciting performance opportunities, especially with their peers.

“It’s a teaching experience for me as a percussionist,” he explained. “I like being able to talk with composers. Most composers’ goal is to have published, mass performed music. If I want to play good music, I want to make sure composers know what percussion can be.”

Composers approach Sound Ecologies with the same enthusiasm as performers like Hunter. Carly Sage, a graduate of Butler’s MFA in Composition with Luke, is a full-time social worker whose compositions have been performed by Sound Ecologies. She also plays violin in the orchestra and teaches private lessons on the side. Classical composing can be a boys club, and as a female creative, the egalitarian format of Sound Ecologies and the mission-driven programming have been instrumental in her feeling not only comfortable, but supported. “People don’t understand how hard it is to get performances as a composer. If I didn’t have Sound Ecologies, I would be just another composer in the Indy area begging the local orchestras to play my stuff.”

Creatives across disciplines are used to not having their work taken seriously. The eternal set-up and punchline of the barista artist sews the seeds for a culture that undervalues the labor involved with creativity. As Rob alluded to in the June chamber orchestra concert, supporting musicians fresh out of college trying to find their place is a key part in stoking creativity long-term.

“That first 50 dollars can be the difference for someone,” Luke explained. “If you can tell other people that you get paid for it, that gives it priority.”

Though that format seems intuitive, it’s surprisingly difficult—especially given that another of the organization’s founding goals was to lower the barrier of entry to the public by keeping all performances free. Compensation was only ever designed to go to the musicians, not the organizers, meaning that one of Luke’s two jobs has been totally unpaid for four years. No one would expect something like this to be a cash cow, but it takes a certain type of person to commit to something solely out of passion, with no expectation of repayment for the thousands of hours of work put into making others’ lives better, not even down the line.

Rob found the fertile ground in which his career could flourish, though it has come with sacrifices that he grants not all people would be willing to make. Charissa and Luke face similar financial constraints. They don’t have much in savings for vacations and are dependent on Charissa’s job for insurance. Rob doesn’t own a television.

That’s the full-out lifestyle, though not all musicians and composers involved with the ensemble go to the same lengths. Most musicians in Indianapolis have careers that look more like those of Carly and Hunter’s.

Sound Ecologies is also not without its struggles. There was, and still is, a question of audience. Classical music institutions have been struggling for years with aging audiences and expanding their reach, and that’s for organizations with marketing teams, robust endowments, and philanthropic support. So if audiences won’t go out to hear a Dvorak or Tchaikovsky, the likelihood they would leave the house for a new music composer they’ve never heard of is exponentially lower.

But for Charissa, a professional pianist, it offers her performance opportunities that she may never get anywhere else. After all, with a new music concert, the audience is guaranteed to hear something they’ve never heard before, and Charissa gets to be the one to premiere it. “Anyone can play Fur Elise,” she explained, “but I’m never going to be better than Lang Lang or any other famous pianist out there, and that’s not what I want to do.”

It takes a lot of faith and optimism to believe that music that, admittedly, is sometimes more fun to play than to listen to, can actually have a positive impact on the world. But most art has an outsized impact on the life of the creator than the viewers. “I wouldn’t be composing anymore if it weren’t for Sound Ecologies,” Carly said. The opportunities are that rare and invaluable. And in the face of federal funding cuts to the arts, the financial pressures for musicians all over the country are more heightened than ever.

But Luke is optimistic about where they are and where they’re going. “We’re doing 8-12 concerts a year, 75 percent of those were paired with another organization and raising funds and awareness for them. It’s a sweet spot. Our next goal is sustainability, and finding ways to continue paying and taking care of these folks.”

About the author: Camille Arnett is a writer of short and long-form fiction and essays. Her writing explores themes of romance, technology, sexuality, and gender. Past writing has appeared in Manuscripts, the Collegian, and Indianapolis Monthly Magazine, and is forthcoming in Quotidian. Born and raised in Indiana, she has relocated to Chicago but still visits Indianapolis frequently.

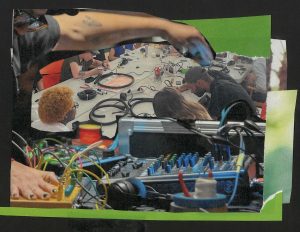

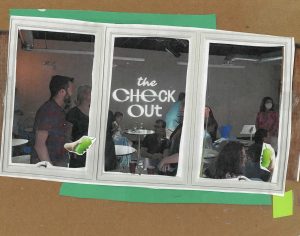

About the illustrator: Bri Robinson is a mixed media artist, analog collagist, sculpture artist, and historian who weaves intricate narratives of love, loss, and identity across the expansive Midwest. Raised in Ohio and now based in Chicago, Bri’s work reflects the rich cultural tapestry of the region, combining personal history with broader societal concepts. Brought up by a large, close-knit family, Bri draws inspiration from the everyday moments and memories that shape our lives, using images found in family photo albums, adult magazines, and personal portraits. Through their unique process of cutting, pasting, and layering, Bri deepens the meaning of these found objects, transforming them into evocative works of art. Bri’s practice is deeply rooted in the exploration of identity, relationships, and the constant evolution of self. By merging archival materials with elements of popular culture, they create thought-provoking narratives that invite viewers to engage with the complexities of the queer experience. Through their work, Bri honors the past while also pushing the boundaries of contemporary art history, crafting pieces that are as introspective as they are expansive. Check out their work on instagram @niq.uor.