Featured image: Elsa Muñoz, The Stewardship of Old Medicine, 2020. A painting of a controlled burn in nature. We see bluish smoke amongst green grass and tree branches, with orange fire burning the leaves. Courtesy of the artist.

“What the Sands Remember” by Vanessa Agard-Jones chronicles sand as a repository of queer memory in the Caribbean Island of Martinique. Sand, a grainy rock mixture found abundantly in the Caribbean, contains island history, ecology, and memory. Since the sand witnesses all, it makes visible what white supremacist, colonial, patriarchal archives render invisible. The sand in Saint Pierre, Martinique is a mix of grey-black volcanic ash, evidence from the eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902. Prior to the eruption, primary sources call Saint Pierre a “Sodom” and a fictional text, A Night of Orgies in Saint-Pierre Martinique by Effe Geache (1892), describes a culture of public intimacy and bar scenes of cross-dressing. Similarly, at Anse Moustique, Sainte-Anne, Martinique, the sand is a material record of queer histories. During dances where queer people have gathered, the sand upturns, lodging itself in hidden places, and holds impressions of movement and footprints on its surface. In addition, the hot temperature of the sand mirrors the men who convened there, calling themselves chaud, which means hot and “in need of release.”1

Agard-Jones’ ecological-archival-fabulation “What the Sands Remember” inspires the work of Chicago-based painter Elsa Muñoz. While Agard-Jones’ work is rooted in Afro-Caribbean and queer studies, Muñoz explores similar threads by unearthing Indigenous histories, Mexican folkloric medicine, and eco-mysticism through her painting practice. The artist has contemplated ideas of permanence within ecological histories, and particularly, within sand, for a long time. On her Instagram, she paired her work Water and Sand with a quote by Jose Luis Borges: “Nothing is built on stone; all is built on sand, but we must build as if the sand were stone.”2 In this interview, Elsa Munõz discusses how she interweaves her cosmology through her work and harnesses the feeling of vastness into sensuous, vibrant, photorealistic landscape paintings.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Chenoa Baker: What were your initial reactions to “What the Sands Remember”?

Elsa Muñoz: One moment that is in direct conversation with my inner dialogue is how Agard-Jones describes time as geological, cosmological, and beyond our immediate scope of vision. The passage is the following: “Today’s sands are yesterday’s mountains, coral reefs, and outcroppings of stone. Each grain possesses a geological lineage that links sand to a place and to its history and each grain also carries a symbolic association that indexes that history, as well.”3

CB: That reminds me of your artistic process and how you start with deep introspection that forays into photography, then painting. Your photorealistic paintings capture unreplicable lighting of a specific time of day, showing the passage of time. Can you describe your artistic process?

EM: I am comfortable with spending time on something and not feeling rushed; of course, deadlines get in the way of that. I have a painting that I’ve thought about and revisited for nine years. It is still not ready to show; I don’t want to talk about it yet nor do I know what it means. I like having reminders that there are things not for quick consumption—things that feel inherently precious because of the amount of time they take to reveal themselves. Time is more than a commodity, it’s an act of care. I relate time to care by spending time thinking, listening, looking, and finally, doing.

CB: Let’s discuss absence-presence, a methodology that Agard-Jones uses to tell histories that were left out by interpreting gaps through the sourcing of atypical primary sources (as opposed to the colonial model, which values primarily written accounts). One way that Agard-Jones employs absence-presence is by meditating on the ever-present sand witnessing queer histories in Martinique. Similarly, your paintings hold a tight field of vision that dwells on a particular moment. The scope of vision makes the viewer focus in on specific ecological formations, such as burning trees, a tornado, and a night-time rising tide. How does the idea that ecological markers contain histories shape the way you depict sand, water, trees, fire, and soil in your work?

EM: That goes back to deep time. All natural elements are living ancestors—that’s the lens that I approach landscape painting with. I am not gazing at an inanimate landscape; I’m looking at living ancestors who hold the longest sense of time. It’s a gaze more readily associated with portraiture than landscape painting, but I approach it with that level of care because I realize I’m painting an ancestor.

CB: Can you talk about documenting marginalized spiritual practices?

EM: That’s a really layered question. The thread that is most pertinent to my work is the reality that curanderismo4 is [documented as] an oral history rather than documented through writing; perhaps it was not meant to be documented. Honestly, I have a mixed reaction to modern curanderos on social media dispersing information that is quite sacred. I have a twenty-year relationship with a curandera. She is a friend and she talks about safekeeping information all the time when she says, “No, you are not ready to receive that information.” I really respect that and I think that is extremely ethical.

I am okay with the absence of information. When things are sacred, information should circulate in the most ethical way possible. There are times when I even think about the things that I want to paint and I ask for permission from my curandera, who I consider a spiritual ancestor. There are times when she says, “No, that information is too intimate and that is not for the public.” I approach absence and presence through the lens of ethics.

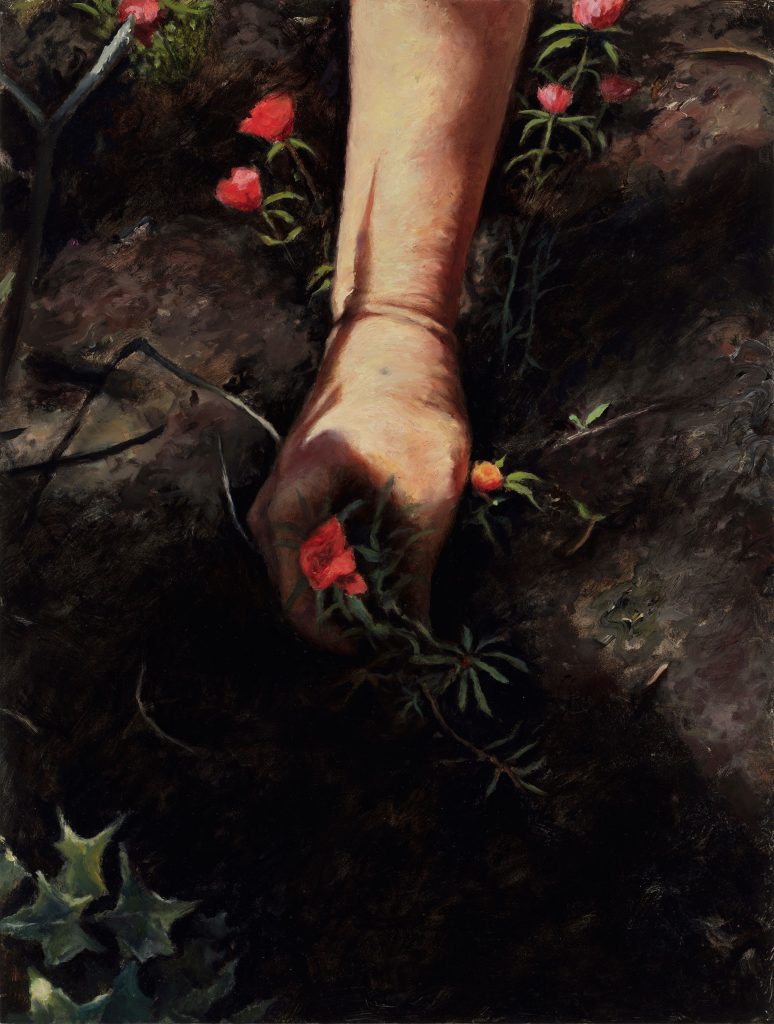

CB: Some of your paintings reference the body, such as Mano Y Tierra 2, which depicts a hand reaching into the soil. Can you talk about how you see human connections with ecology?

EM: My lens regarding human interaction with the earth is deeply informed by the stories from my childhood. As a child, I didn’t have the term ’magical realist,’ it was just my mom telling stories about growing up and I realized in my twenties that magical realism is a genre. In any case, she tells a story about fire ants saving her life. My mom grew up really poor in central Mexico. As a child, she worked in the fields alongside her father and she describes tilling the ground before planting seeds. In the process of unearthing things, small snakes, mice, scorpions, and things that you don’t want to step on emerged. Since she couldn’t afford shoes, this experience traumatized her. Within curanderismo, that type of trauma is called susto and it literally means “fright,” but we now know it as PTSD. When addressing susto, the cure is usually another strong fright—it’s the idea that like cures like.

She ended up getting really sick—vomiting and a fever that wouldn’t break. When you are really poor and in a place without medical services, that can be a death sentence. Thankfully, a wise neighbor heard about her condition and knew what to do. She took her to a red ant hill, picked her up, and placed her on top of the hill (red ants are vicious, especially when you are stepping onto their colony). Immediately, the ants swarmed her little legs. But miraculously, once they reached her knees, they fell over, curled up, and died. None of them bit her and she was instantly cured. The ants sacrificed their lives by absorbing my mom’s susto. This story—this idea that ants can conspire to heal you—informed an enchanted way of thinking about the natural world [for me]. I paint that magic into things because that’s where I am coming from.

CB: What do you seek to unearth in your work?

EM: I could name ecologists, but when I am painting, I want ancient things to come through. This sounds extremely romantic, but I want to access things that even I don’t understand and that I can’t name. There are energies and spirits that are around us attached to all earthly things that are watching and participating constantly. I have respect for that type of animist lens, so I leave room for that.

It goes back to: does this image make me feel something more deeply? Does it make me feel that there is magic? Does it make me feel that intimacy is a possibility? These bigger ideas are usually tied to feeling that I am in charge of stewarding a bit of magic and intimacy in my paintings, because that’s my strength as a human, beyond being a painter.

CB: What are your thoughts on landscapes recording histories of flourishing and trauma?

EM: I keep thinking about the book The Body Keeps the Score [by Bessel van der Kolk], which talks about how trauma lives in our physical bodies. That lens shapes my understanding that the earth is a body and we are many bodies within that large body. I’m interested in somatic healing (practices that release trauma through physical manipulation). That interest helps me think about controlled burns as a somatic healing modality because setting fire to something transforms the original material into smoke and ash. And that transmutation is a form of somatic healing. Because I have that language of somatic healing, I think about it in those terms. The earth needs to release its trauma, just as we do.

Desahogamiento literally translates to undrowning. I’ve always heard my mom casually say desahógate, which means “undrown yourself” and that is the way this term came to me. It is a somatic practice of transmuting grief in a physical form. This meant, to my mom, to sing it out, go out to play, or talk about it. When natural disasters occurred, my mom would say: La tierra se está desahogando (the earth is undrowning itself). The earth needs to address its own pains (it has to desahogarse). It is not just an inanimate landscape for us to live on; it has its own feelings, sovereignty, and need for healing.

CB: As we witness many hurricanes and tropical storms, that is an apropos statement. Thinking of natural disasters as an undrowning makes me feel that we should listen to the earth more.

EM: Three years ago, I read Woman Who Glows in the Dark by curandera Elena Avila. Through that book I realized that desahogamiento is an actual folk medicine technique. Avila defines one type of curandera as being a consejera (counselor). Consejeras offer deep spiritual medicine by simply listening to someone undrown themselves, by being a witness to someone telling their story. I think that is so powerful—this idea that simply being a deep listener is literal medicine. This perspective clarified what I was trying to do through my quiet images. I want to make paintings that are so quiet they can listen to someone. I know I’ve felt listened to by works of art, so I know it’s possible.

CB: How do you incorporate your personal life in what you paint?

EM: Even if I don’t talk about it in exact terms with the general public, many can perceive what I go through in my work. I’m talking about ideas like trauma and regeneration because I live them constantly. I value the approach of not defining myself as having arrived at something or showing someone a polished and finished project. I leave room for brokenness and grief because those processes are essential to showing up in the world in a humane way. Being in touch with your own brokenness makes you a more gentle person; I value that beyond painting.

I am of the school of thought that all art is self portraiture. I see my work and I’m like, “it is so obvious what I am going through at that moment.” I use the language of landscape and then address it through beauty because of this instinct I have for transformation. I never simply want to observe and record. There is always an instinct to make something beautiful and it’s an impulse I’ve carried since childhood—how do I make this beautiful?

CB: Revisiting what you said about not wanting to simply “observe and record,” that brings me back to Agard-Jones’ essay. Cold observation is colonial and you push against that by listening to your subject.

EM: Reading the essay brought to mind a famous quote by Octavia Butler, who says, “All that you touch, you change; all that you change, changes you. The only lasting truth is change; God is change.” It goes perfectly with the idea of queering the landscape; queering is a synonym for blurring and complicating boundaries. I’ll take a step further and call it porosity. It’s the idea that landscape and humans absorb information from one another by being in each other’s presence. We are ever-changing; there is no such thing as hard boundaries or borders. We are in flux all the time.

____

Endnotes:

1Agard-Jones, Vanessa. “What the Sands Remember,” (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 328.

2Welland,Micheal. Sand: The Never-Ending Story, (Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 234 qtd. Jose Luis Borges, 1972.

3Agard-Jones, Vanessa. “What the Sands Remember,” (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 328.

4“Curanderismo is a type of holistic folk medicine traditionally used in Mexican and Mexican American cultures. Followers of this healing system define disease as having both biological and spiritual causes and, therefore, utilize curanderos who treat on three levels—material, spiritual, and mental.”— Torres, Nigel and Janet Froeschle Hicks, “Cultural Awareness,” Ideas and Research You Can Use: VISTAS, 2016, 2.

Chenoa Baker’s curatorial and writing practice meditates on the intersection of Black art, spatial studies, and BIPOC feminisms. Currently, she is based in Massachusett, Wampanoag, and Nipmuc land as a Museum Fellow at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. Her work is featured in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Burnaway, Art & Object, Black Art in America, and Sugarcane Magazine. Learn more about her on LinkedIn or Instagram.