As a non-degreed performance artist/arts administrator in Clout City, there are some burning questions that I’ve been grappling with in my own artrepreneurial career. How do we interdisciplinary experimental performance artists (especially female-identified/queer/POCs) valuate and articulate our own labor/practice/product? Which factors have historically kept us from valuating our own labor and production costs? When will major cultural funding programs stop supporting project budgets to the exclusion of operational budgets (“We support art, not artists.”…WTF?!)? How do we navigate around these systemic, limiting factors and break the fucking glass ceiling? How do we avoid our business models/processes and end products succumbing to the shape of pervasive neo-liberal ‘free market’ capitalism?

Because performance is fundamentally experiential/temporal/ephemeral, the traditional market value of performance has hinged on being in the room —just like any other Event. The tastes and expectations of the Gentry—academics, historians, politicians, critics, well-heeled patrons, foundations and institutions, white men—continue to dominate the arts valuation process, as well. Recent investigative articles and survey data expose some pretty dire trends in arts education/credentialing and poverty/economic inequality among artists (read the thoroughly-researched and insightful “Art Without Artists” by fellow SIFC contributors Eunsong Kim and Maya Mackrandilal).

Since we still have Net Neutrality (for now) and new models of Social Entrepreneurship in the arts AND the industrial world, I contend it is our responsibility as 21st-century cultural producers, embodied storytellers, and artrepreneurs to no longer be complicit in the devaluation of our creative labor and product. There can be no art without artists, so for the following interviews, I invited some of the fiercest Chicago-based experimental performance artists to join me in a candid conversation about these topics and to share veritable snapshots of their performance career prospects in “the City that Werqs”.

——————————————-

Darling Shear

Felicia Holman: How do you articulate the value of your work? To whom do you direct your articulation?

Darling Shear: It’s a educational tool to help start conversations, and it’s open to all.

FH: How do you determine your asking price? Meaning the artist fee, admission fee, etc.

DS: I look at the venue and how popular it is and how much the drinks are.

FH: Where and when do you find resistance to your asking price, and what are your negotiation tactics and strategies?

DS: I don’t anyone I have finally figured out my worth. It’s interesting. And when talking about what all I need and am expecting I’m kind about it and people always blown away by it.

FH: How many day jobs do you have, and do they correlate with your artistic practice?

DS: My day just is dance and therapy work. My therapy work feeds my artistic body a lot. Because it helps me figure out how to make my art a therapeutic body of work that helps people connect the dots in their life.

FH: How would you describe your knowledge of market forces and your personal relationship with money?

DS: I worked in marketing for a little, and it was a interesting land. I’m very laidback and believe the people that were in the space together are suppose to be there at that time. So there is no real big push on marketing, but I’m getting better about it. And my relationship with money is improving… I’ll leave it at that.

FH: As an independent performing artist, do you document, merchandise, and/or package your shows for residual revenue outside of ticket sales?

DS: No I’m actually not the best at the branding of myself. I’ve had issues with this for years. I’m very lax about people seeing my work.

FH: Do you consider yourself an emerging or mid-career artist and do those labels affect your asking price (in your own head)?

DS: I consider myself still rising but I also know that my work is amazing. I had to get comfortable asking for what I know my work is worth but now I ask it and sometimes demand it easily.

FH: Out of all your travels, what’s the tie that binds your work/practice to such a commercially-driven city like Chicago?

DS: There is much social work to be done in Chicago and I feel I have a voice that is aiding the shift in this city.

Darling Shear is a Chicago native with roots in Atlanta, where she started her dance training. She attended North Springs Charter School of the Performing Arts and began dancing professionally upon graduation in 2008. In 2011, Darling founded Suna Dance–a collaborative performance artist group. Currently, Darling is a Chicago-based freelance dancer/choreographer and has worked with The Fly Honeys of the The Inconvenience and apprenticed with the Cerqua Rivera Dance Theatre.

——————————————-

Kiam Marcelo Junio

Felicia Holman: How do you articulate the value of your work? To whom do you direct your articulation?

Kiam Marcelo Junio: Primarily, I articulate the value of my work through its impact – whether perceived, received, affected – towards an audience. There’s a tangible effect, a movement, a stirring. My work seeks to begin and continue discussions, questions, and exchange of ideas. More than monetary value, performance creates new opportunities for meeting potential collaborators and creating new work. Therefore, when deciding whether or not to perform for an event, I take these factors in mind: Is what I’m giving (of my time, heart, body, and soul) worth what I’m getting back – both qualitative and quantitative measures factored?

When I began performing in nightclubs and queer events, the money was never the value that I was seeking. But the climate is different now, we know our worth as performers, we know how much we are risking of ourselves. I know what I’m willing to do and for what or how much. I’d like to believe that perhaps performance itself, in using the body as the primary work site, can help to empower the performer in creating their own value exchange system.

FH: How do you determine your asking price? Meaning the artist fee, admission fee, etc.

KMJ: Quantitative measurement of work value is something I’m always learning and relearning. It’s a constant renegotiation and is based on many factors: cost of materials, travel expenses, costumes, payment of collaborators (musicians, video editors, photographers, dj’s, guest artists). I also like to estimate a realistic work-per-hour rate, which includes rehearsal, research, and production time.

Artist fees vary widely depending on the space, organizer, institution, or event. I expect to get paid more from institutions with larger budgets than DIY events, for example. But sometimes the opposite is true. Basically, I say to myself, “Unless I want to volunteer my time and effort towards a good cause, I expect to be paid for a performance no less than ‘blank’.” I have a base rate that I hold as a standard for myself. Luckily, this number has built up steadily over the years, but it takes constant advocacy for my work to make that happen. With admission fees, I’m a fierce proponent of a sliding scale system, with or without a suggested donation range. I think it’s important to empower and respect audiences, rather than only allow a privileged few to observe.

FH: Where and when do you find resistance to your asking price, and what are your negotiation tactics and strategies?

KMJ: When I’m contacted for an opportunity and they ask, “Would you like to submit/perform work at ‘so-and-so’?”, and I ask, “What’s the compensation?”, and they say there is no budget, I have to ask if there are any other perks: drink tickets, free admission, a manicure, a gift bag, whatever. Give me something else, or else you’re obviously not valuing my time. Exposure is no longer enough. I need to survive in order to make more work. I appreciate and advocate for transparency. I prefer to work with people who know where I’m coming from and who understand that life as a working artist is not easy. If necessary to make myself clear, I am not above saying, “I would like to get paid so I can pay my rent.” If the budget is only “so-and-so”, let me know. Maybe there are more important reasons to perform that trump getting paid, so I take those chances too. But it has to be worth my time and effort, and born from mutual respect.

FH: How many day jobs do you have, and do they correlate with your artistic practice?

KMJ: I walk dogs for a dog-walking company and run IAMKIAM Studios, a freelance portrait photography and event videography business. I primarily work with local queer artists, events, and promotional campaigns. I also have a clothing line called QIAM on Etsy, which currently sells tank tops, jock straps, and wallets, and it is expanding this summer. Previously, I taught yoga classes at a studio and privately, and sold cheese at farmer’s markets. My yoga teaching and practice in particular has expanded and continues to influence my performance work. My photo and videography work and art spill into one another. The dog walking and cheese selling has affected me more on a psychological level, but they still inform my practice one way or another. Making clothes also improves my skill in creating fabric sculptures, props, and costumes.

FH: How would you describe your knowledge of market forces and your personal relationship with money?

KMJ: Money is a beast. It’s a man-made invention, like most other concepts. But in perceiving and giving money value, it becomes a “real” and tangible thing. Money drives so much of the world’s movement, and I think it is ultimately a destructive force, a “cheap” alternative to the use of the transformative powers we actually have as humans, and as living bodies. Money flattens everything we do and are capable of doing into an easy exchange of symbols. That being said, this is still the world that we live in, and with which we must contend. I accept this now. I didn’t for the longest time. I truly wanted society to abolish money and return to a barter system and small, local, and gift economies. It’s a wonderful idea, and I think we can create these economies on personal scales. I already see this happening around me. My friends are my colleagues, collaborators, and business partners. We pay one another for our labor, even if it’s $5, $20, $100, or a bag of weed. There’s more to be exchanged than money, but we also understand that we need it to survive, and it allows us to plant and sow seeds for the future. Understanding this, my relationship with money is that it doesn’t run my life, but rather, augments it. Knowing this for myself, and surrounding myself with people with similar values, keeps me working hard for the greater work, and not only for financial gain.

Arts organizations and spaces are now becoming more aware of the need to pay artists. We’re not just playing games anymore. We’re creating change, and that requires support. There needs to be more equal and fair distribution of resources and capital. I’m very suspicious when an organization asks for a performance, or art piece and say, “But we don’t have a budget for ‘blank’.” As working artists we have to demand an answer: “Why?” Why, in creating an event, is the artist the last to get paid? I was recently asked by a local Chicago arts organization to submit video work for a gala with ticket prices over one hundred dollars. Who was the target audience here? The lineup included some of the most influential underground working artists in Chicago, and yet, the organization only offered the artists a discounted ticket. Why would I have to pay to see my own work? It made no sense. I didn’t fight it at the time, thinking that the greater cause of the organization was worthy to volunteer my time for. I was busy that evening anyway. I excused myself. I could have made my dissatisfaction known, and I didn’t. I could have advocated for my peers, and sadly, I didn’t. I own up to this, but I’m better informed now, and I won’t let that happen again. Organizations need to be held accountable. Artists need to get paid a fair value for our work in creating and redefining culture. And we can only do this if we speak up and advocate for ourselves and one another.

FH: As an independent performing artist, do you document, merchandise, and/or package your shows for residual revenue outside of ticket sales?

KMJ: I document my work, but generally for documentation’s sake, or as raw material for future work. I’m more focused on building my body of work for workshops and talks, rather than merchandise. But some projects are more conducive to commerce than others.

For example, I’m currently writing and editing Filipino Fusions: A Culinary Critique, a cookbook based on the web series I created with Inside the Artist’s Kitchen. Jerry Blossom, my alter ego / performance persona, hosts a cooking show creating vegetarian Filipino food. We worked with several sponsors and supporters who donated their time, space, products, and talents to make the show and the live demonstrations happen. The kind of qualitative value the show creates allows us now to produce a tangible item: a cookbook that can exist as a product to distribute. Beyond recipes, the book includes poetry, images, essays, interviews, and collaborations with local artists. Recently we had an unsuccessful Kickstarter campaign intended to raise funds for printing. We learned a lot from this minor setback, and it’s allowed us to rethink our strategy. Because the work is worth doing, it’s worth continuing.

FH: Do you consider yourself an emerging or mid-career artist and do those labels affect your asking price (in your own head)?

KMJ: I consider myself an emerging artist but it doesn’t really run my practice. All I use the label for is to say to myself that I have much more work to do. It affects my asking price, but I don’t think unfairly.

FH: Out of all your travels, what’s the tie that binds your work/practice to such a commercially-driven city like Chicago?

KMJ: I am here for the community I’ve found and am helping to cultivate. I keep hearing that Chicago is a Working city, that people come here to work hard, and I definitely feel that with the people I surround myself with. We work hard together, which is much more effective than working hard alone.

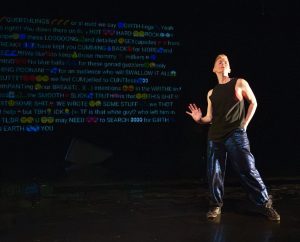

Kiam Marcelo Junio is a Chicago-based interdisciplinary artist creating work through various media, including, but not limited to, photography, video, performance (blending elements of butoh, drag, and pop music), installation, and culinary arts. Their research and art practice centers around queer identities, Philippine history and the Filipino diaspora, colonization and American Imperialism, the politics of visibility, and social justice through collaborative practices and healing modalities. Kiam served seven years in the US Navy as a Hospital Corpsman. They were born in the Philippines, and have lived in the U.S., Japan, and Spain.

For more information, read: “Seeing and Being: Kiam Marcelo Junio Fuses Genderqueer Identity and Filipino Food Culture In Web Series and Cookbook”

——————————————-

Sojourner Zenobia Wright

Felicia Holman: How do you articulate the value of your work? To whom do you direct your articulation?

Sojourner Zenobia Wright: This is very challenging to quantify because my work is truly not separate from the way I choose to wake up in the morning, how I brush my teeth, the conversations I have everyday and how I feel about them, where I am in my life, etc. When I get a specific commissioned piece the process begins as soon as I say yes to it. There are quantifiable hours in the studio, but there are also sporadic bursts of inspiration that it is my duty to catch in the moment or they are lost forever. Fleeting songs, feelings, and more. Do I put a price on those moments? All this is to say, I have not figured out how to articulate it. I ultimately just throw out a number. One hundred dollars for the process and the performance sounds and feels good. In all reality though, I am usually very intimately connected to the project on many different dimensions, as well as performance being my calling, and therefore it is something that I lose time spent curating, directing, and performing, and there are usually costumes and other technical things to be accounted for. I should easily be able to ask for five hundred dollars. As far as the audience and what they get out of it, my work is valuable to the viewer in as much as they are familiar with or curious about the unseen forces that guide us all. This is, of course, unless I am creating something for someone else’s vision and am not free to go as deep as I innately do.

FH: How do you determine your asking price? Meaning the artist fee, admission fee, etc.

SZW: This is usually determined by my relationship to the client. If they are friends I gladly do in-kind performances. If they are in a position to pay I request fifty dollars. For people I don’t know and those I know are capable of offering more my pricing is one hundred dollars and up, depending on the complexity of the performance.

FH: Where and when do you find resistance to your asking price, and what are your negotiation tactics and strategies?

SZW: Honestly the resistance is my own at this point. I hesitate to put a proper number out there for fear of being denied. I feel like people don’t understand what I do and that they often don’t take performers seriously, or they think we are just having fun and messing around and so to request to be paid over a hundred dollars I imagine people would laugh at me. Especially because my work is not traditional “acting” or “dance”, training may not be recognizable. I feel like work that one can put a finger on style-wise is more likely to be welcomed and compensated. Work that is nontraditional is harder to trust. But I also am finding more and more folks who truly value the process of artmaking, whatever it looks like.

FH: How many day jobs do you have, and do they correlate with your artistic practice?

SZW: At the moment I am a Fine Art Model full time. I sell clothes on etsy, and I am a distributor of essential oils. I love all of my jobs, and they align with my artistic vision of truth, health, artistic collaboration. The income from these jobs is completely unpredictable however. Just three months ago I moved in with my mother so that I could save money for all of the traveling I like to do. I cannot stay in this position much longer however, and when the tides shift and I am living on my own again I will pick up at least two more consistent part-time jobs.

FH: How would you describe your knowledge of market forces and your personal relationship with money?

SZW: I don’t know what market forces are. I could definitely use a course in money management. Right now, I have a good relationship with money. I have done a lot of personal work around knowing that money isn’t who I am and that I am lacking nothing! I spent three months in a Buddhist monastery a few years ago. There I directly experienced that we as humans don’t need much AT ALL to survive, or to be happy. I don’t worry about money much, and even when I have just a very little bit of money, I am always looking to see where I can support other artists whether I show up at performances or contribute online.

FH: As an independent performing artist, do you document, merchandise, and/or package your shows for residual revenue outside of ticket sales?

SZW: Within the past year I have felt the devastation of applying for grants and residencies and not having adequate documentation of ALL of the work I have done over the past seven years. I am diligent about recording my work now, though I am not sure I understand how recordings of my work would grant me residual revenue.

FH: Do you consider yourself an emerging or mid-career artist and do those labels affect your asking price (in your own head)?

SZW: It feels like I am just now emerging in a way where people around the city in the queer and avant-garde performance art world Are just beginning to know that I’m here and callon me to create work. However,I have been creating work since 2008. Yes this does have an effect on how comfortable I am with asking for what I’m worth. It feels like I have to gain peoples trust more but really that’s just when I am making work for more mainstream audiences, and I have to prove to them that I’ll do quality work, and that I won’t do anything too weird. But with the audience that I feel really respects my work for what it is I have no problem asking for what I’m worth, I just hesitate because many times the peoplecurating spaces where my work is valued don’t actually have a huge budget to pay me what I really would like to receive.

FH: Out of all your travels, what’s the tie that binds your work/practice to such a commercially-driven city like Chicago?

SZW: The nature of Chicago is separation, difference and division. I see this in the Way not only communities but artists separate themselves into different movements of creativity. The queer movement, the afro futurist movement, the mainstream dancers and actors, and within all of these movements there is a way to be politically correct inside of them. I don’t see a problem with this, it just can be separatist at times with all the jargon. And I believe this atmosphere creates artists that have a strong desire to connect with all of the other artists but are also working very hard to define exactly who they are and manifest the community that will support them. This makes Chicago an exciting place because I think it is it is an example of exactly what needs to happen in the world, people need to find their tribe and feel safe and be respected in the values of their tribe, but we also must must must find a way to commune together, all of the tribes and have it be okay to leave and go back home to the people we feel most comfortable building the communities we feel most comfortable in. I am not Bound to Chicago, I’m always traveling but it seems like Chicago is where my muse thrives the most so far. I hop around from community to community I have many tribes here and hopefully I am one of those who can continue to bring them all together at the most cosmic times and in the most cosmic of ways.

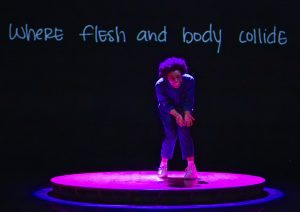

Sojourner performing a tribute to Nina Simone

Sojourner leading a vocal workshop

Sojourner Zenobia Wright founded Soul Journey Projects in 2008 to fulfill her desire to direct. Inspired to investigate the ways art impacts the energetic body of a performer and audience, she became particularly skilled at bringing out raw and magnetizing performances in both her company and solo work . Sojourner challenges depth in the underground performance scene with her appearances at open mic’s, theatre festivals, and through her original productions in nontraditional spaces, neighborhoods, vacant lots, bars, restaurants, loft spaces, and the streets.

Lifelong Chicagoan Felicia Holman is co-founder/Communication Director of Honey Pot Performance, Marketing/Studio Manager at Links Hall, and curator of the 4th annual Columbia College Chicago student exhibition, Engage/Connect. With Honey Pot, Felicia creates and presents original interdisciplinary performance which engages audience and inspires community. Credits include The Ladies Ring Shout (2011), Price Point (2013), Juke Cry Hand Clap (2014), and current work-in-progress, Masking Her (2015-2016).

Lifelong Chicagoan Felicia Holman is co-founder/Communication Director of Honey Pot Performance, Marketing/Studio Manager at Links Hall, and curator of the 4th annual Columbia College Chicago student exhibition, Engage/Connect. With Honey Pot, Felicia creates and presents original interdisciplinary performance which engages audience and inspires community. Credits include The Ladies Ring Shout (2011), Price Point (2013), Juke Cry Hand Clap (2014), and current work-in-progress, Masking Her (2015-2016).

In addition to performing, Felicia writes essays & content for online outlets including Sixty Inches From Center Magazine, The Working House Blog, and This Is HCL (the High Concept Laboratories blog). Felicia is an admitted Facebook junkie and begins a five-month artist residency at the Washington Park Arts Incubator this April. Felicia sums up her dynamic artrepreneurial life in 3 words—“Creator, Connector, Conduit.”

Header image: Spray Paint Not Bullets mural at Washington Park Arts Incubator. Photo credit: Felicia Holma