As many contemporary artists, arts organizations, and other cultural laborers continue a decades-long trajectory of reorienting their practices more deliberately towards and within the social world, forms and approaches have morphed through a collective re-imagining of the production, dissemination, and sociopolitical potential of art. These modes have sought to broaden access and participation in the arts, transform relationships between people, forge practices rooted in ethics as much as in aesthetics, and other similar gestures toward aligning art with notions of social justice and reform. Yet amidst this grappling, a number of unresolved riddles remain regarding art’s place in daily life: who is art’s “community,” and what exactly do we mean by “community”? What is art’s relationship to democracy? Can increased access to the arts also advance civic participation more broadly? What is the role of the artist in society? Can art and artists be catalysts for social change — and should they?

Such issues and questions reverberate through the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum’s current exhibition Participatory Arts: Crafting Social Change, which explores the influence that Addams and other social reformers have had on visual and performing arts in Chicago through historical and contemporary practices of bookbinding, ceramics, theater and performance, and art therapy. The show is structured by pairing current practitioners alongside objects and artifacts from the Hull-House Museum archives and UIC Special Collections relating to important figures and moments in the settlement’s history. In addition to the exhibition, programming has featured a series of workshops led by the featured artists, as well as a symposium that explored the historical legacies, and current potentials, of art to incite social change.

Founded by Addams and Ellen Gates Starr in 1889, the Hull-House symbolized reformist ideals of the Progressive era (1890s–1920s), and was part of a nationwide movement of settlement houses which in many ways sprung up in response to the exploitation and social stratification of the Gilded Age. Operating under the notion that art and education are vital components of democracy and community life, these sites offered resources and creative outlets for new immigrants and poor and working-class neighbors in their local area.

As recently arrived migrants from Latin America and Europe were recruited into brutal factory work in harsh conditions for low pay, Hull-House envisioned its art classes and programs as a way for these groups to come together, learn new skills, and partake in more dignified forms of labor through creative production. From 1927 to 1937, the Hull-House Kilns program existed on site as a commercial pottery studio to produce and sell dinnerware and decorative items, as well as to teach ceramics and mural classes to adults and children. Chicago saw a major increase in Mexican migrants funneling to the Southwest and South sides during that time period, and Hull-House became a gathering spot for them — including many artists and students who took ceramics classes and made pottery. Through the styles, methodologies, and cultural traditions they carried with them, these Mexican migrants left an indelible, though largely under-recognized, mark on the pottery that was produced at Hull-House, as well as on the mass-scale commercial producers who would appropriate that work and eventually render the Hull-House Kilns obsolete.

Within the Participatory Arts exhibition, these specific narratives serve as a backdrop to frame the current work of Nicole Marroquin, an artist, educator and researcher whose interests include Latinx futurism, spatial justice, public archives, and histories of social movements in Chicago and beyond. Often working collaboratively and with students, her practice unfolds through printmaking, ceramics, and sculpture, and is frequently derived from primary documents and other archival material.

In late November, as the racist leadership in the U.S. government began directing military personnel to use lethal force against the migrant caravan approaching the U.S.-Mexico border, I met with Marroquin to discuss space and place, the border and immigration politics, her recent research about student-led activism in Chicago from 1968 to 1973, her work with students at Benito Juarez Community Academy High School, and their combined contributions to the Participatory Arts exhibition and programming, among other topics.

This interview is part one in a three-part series (see part two here and part three here) of dialogue with artists featured in Participatory Arts, on view at Hull-House until May 2019. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Greg Ruffing: I wanted to start by asking you about this strong spatial politics that’s in your work — sometimes more overtly and sometimes more in the background. So maybe just to talk about that, as you’re looking at the South and Southwest sides of Chicago, relative to where you grew up and where your family is from.

Nicole Marroquin: Well I’m interested in a couple different, broad subjects there. I think a lot about belonging, and how [Roberto] Bedoya talks about belonging. It really resonated with me. And how, when he was working in Pima County in Arizona — here you have this super-charged atmosphere that’s right on the so-called “front lines” of the immigration “crisis”. And then all the people there have this questionable membership, all these other brown people and Natives, who for some are the “rightful owners” or original inhabitants. A lot of these frames are really based on white supremacist notions, so it’s dicey. But, you know, the rightful owners of the country are inhabitants, and then trying to keep out some people that aren’t supposed to be here — I mean, the tactics of the U.S. government have been to take two tribes that were not getting along, cut one in half, and sandwich them around the other.

I think this whole situation going on with the northern migration that’s happening from Central America is one hundred percent continuation of the destruction of Indigenous people’s lives, and ongoing cultural genocide. […] I can’t stop thinking about the situation in south Texas, and my family being from both sides of where the border is now, people moving back and forth continuously, and then people moving in the interior state of Mexico and Texas during the Revolution and then being forced back. It’s like a circular migration, but within a really tiny region between San Antonio, Nuevo Laredo, and then a little bit further south. But then I have a lot of questions about how people land here [in Chicago] too, how people get to be in a neighborhood, what are the actual forces that are making individual people decide to leave or stay.

GR: So you were born and raised in south Texas?

NM: I was born in San Antonio, and my parents were born in San Antonio, and their parents were born in San Antonio or nearby. And after that then it just starts to move around. I mean, it’s so segregated there. I consider my family as part of the Northern Migration. We got the fuck out of Texas. And I’ve got people close to me who were chased out of places in Texas because they didn’t kowtow to the dominant politics. But when I was very small, we moved to Ann Arbor. It was super radical, but there were no other Mexicans there. It was not super diverse. Later I was looking at these archives in Houston and I found out about the Chicano movement in Ann Arbor and I was like ‘oh my God, I was there, I was the babysitter at this meeting, watching the younger kids.’ So I get it now, that my parents were involved in stuff — they weren’t artists, but they were hanging around a lot of artists, which is probably what happened to me. Really rad, really progressive artists there who weren’t afraid to experiment and weren’t afraid to get in the face of the establishment. And they left a really great print publication trail that I later followed. But I wish my people had told me, for example that my uncle was at the Crystal City uprisings in south Texas. And then all this Chicano organizing in Michigan, my family was there, and I’m still in contact with their friends who were the leadership. All this stuff was around, so it really informed my thinking. There was a lot of Midwest organizing, and that’s what I’m coming across now as I’m trying to retrace stuff here. I’m really excited by the Chicano organizing in the Midwest.

GR: Can you talk about your relationship with Pilsen — what brought you to Pilsen, etc.? Again, thinking about this resonance of place and community in your work, are there ways that being here has influenced or driven your work?

NM: Well, I’ve had a couple times, even recently, where I felt like I gotta get out of here, like I can’t be here or I don’t belong here. And I’ve been told I don’t belong here several times by people. Its weird, I’ve never felt like I need to be in agreement with everybody, and I like to hear critiques. But I also think that some of this ‘do you originate from here’ stuff is really rooted in white supremacy. It’s an immigrant community, and I don’t belong anywhere. So I know that if I go back to Ann Arbor I don’t belong there, or if I go back to south Texas I don’t belong there. Texas lets you know in a loud, clear voice when you aren’t wanted.

GR: I can see how that would create this focus for you on belonging, or even “disbelonging” in how Bedoya talks about it.

NM: Yeah, and also feeling like you don’t belong but that you have a right to be here is Texas — that’s at the center of where my thinking comes from. It’s just that kind of tension that makes me feel at home. My kids go to school in Little Village, and its really important to me that they don’t grow up feeling like they’re being singled out or that they’re gonna be followed around in stores. Shit like that — that’s how I grew up, and it damaged the shit out of me. I’m still dealing with it. I mean, Ann Arbor was harsh. Racism is really painful shit — you can survive it, but you’re gonna feel really bad about things. Where I grew up, half of my neighborhood was Black, and I spent a lot of time in Black spaces — and then encountering anti-Blackness in Mexican communities, I’m like, I just can’t. That is really hard for me to put up with. One thing about Pilsen that I really love is how immersed in Black culture the Mexican Americans are here. People who are my age who grew up here — like, who else has the entire record Love Jones memorized in order? Mexicans from here! They’re super hardcore into soul and R&B music. Oldies.

And I know that particularly Motown had an influence on my parents and their decision to move to Ann Arbor. Oh, we’re a music-obsessed family. I just wanna talk about what people were listening to, you know? And then I wanna know what people were wearing. I’m really interested in being able to recreate what things looked like, because ultimately what I’m interested in is getting this information to teenagers, and for them to understand stuff. They’re gonna understand it through the music and fashion. But what I’m also getting at is, I’m not a historian [laughter].

GR: But maybe in a good way, right?

NM: Yeah, I feel really glad to have that kind of freedom. I’m teaching this class right now with Josh Rios, called DIY Time Travel, and it’s all about imagining spaces in between the known [and the unknown], and what can you sandwich in between — and not being so stressed out about the unknown. I felt like I was being attacked by what I couldn’t know, and I’ve been trying to put these pieces together and to open them up as opportunities or provocations. The thing about this area [Chicago] is, the racism just really fucked people up, and it’s like people have become convinced that their history isn’t as important as it is, or isn’t worth telling people about. At least, that’s one of the vibes I’ve gotten. When I ask people to tell me about the history, I’ve heard them say, ‘why do you want to know?’ As if they are worried. I have to remind myself that people were terrorized by police here, [by] both the Red Squad and individual rogue cops. This is the West Side, and this kind of thing still goes on. The message that people’s history isn’t important is evidenced by the fact that the local community newspapers that reported, often in Spanish, have not been collected by any of the archives in Chicago. That’s another story, but it speaks volumes about how little people thought about this community, and explains how so little is known about these histories of struggle.

GR: You’ve been working with this history of student activism on the South and Southwest sides, specifically in 1968 and 1973. Can you tell me a little bit more about that, and how you’re reflecting on that nearly 50 years later?

NM: Basically, it’s the story of these two schools that had student and community-led uprisings, and they’re histories that aren’t written in books, that aren’t known by the people who live the legacy of the struggles, or who live in proximity to where the struggles occurred. These were violent events, and by that I mean, police attacked and injured people during these incidents, and because of how Chicago works, you never hear about how police attacked and injured innocent people who were exercising their constitutional rights to protest, but you also don’t hear about the struggle in general. Here I am two blocks from the site, and a scholar of education, and I knew nothing about this?

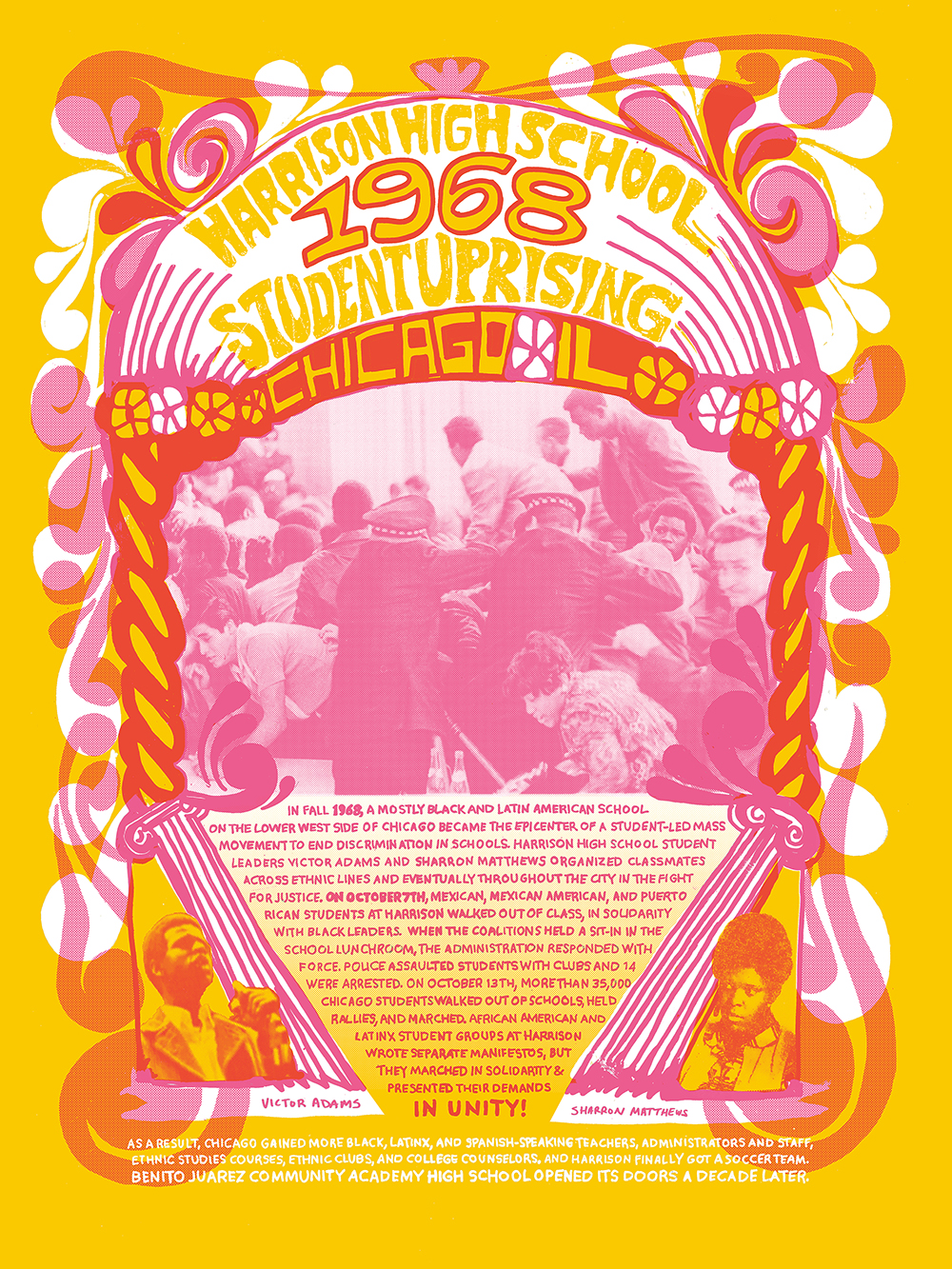

In fall 1968, this majority Black and Latin American school on the Lower West Side was the epicenter of a mass movement by students to end discrimination in schools. Harrison High School student leaders Victor Adams and Sharron Matthews, who were part of a youth organizing group called the New Breed, organized students at their school to walk out of classes each Monday to protest poor instruction, lack of college prep, lack of ethnic studies and lack of student voice in decision-making at the school. Eventually, the movement crossed ethnic lines and Mexican, Mexican American, and Puerto Rican students at Harrison walked out of class in solidarity with Black students. When the coalitions held a sit-in in the school lunchroom, administration called police, who assaulted students with clubs, and 14 [students] were arrested. [A few days later] more than 35,000 Chicago students walked out of schools and held rallies throughout the city.

It’s important to note that in 1968, Mexicans and Mexican Americans in CPS were classified as white, so when Latin American students claimed to have an 80 percent dropout rate at Harrison, there was no evidence on paper. There was one Spanish-speaking staff person for the estimated 1,200 Latinx students at Harrison. Also, The Red Squad [a secret arm of the Chicago Police Department] had begun tracking organizing activity, and they were believed to have been involved in harassing student and community organizers. The principal of Harrison threatened a Mexican student organizer with deportation.

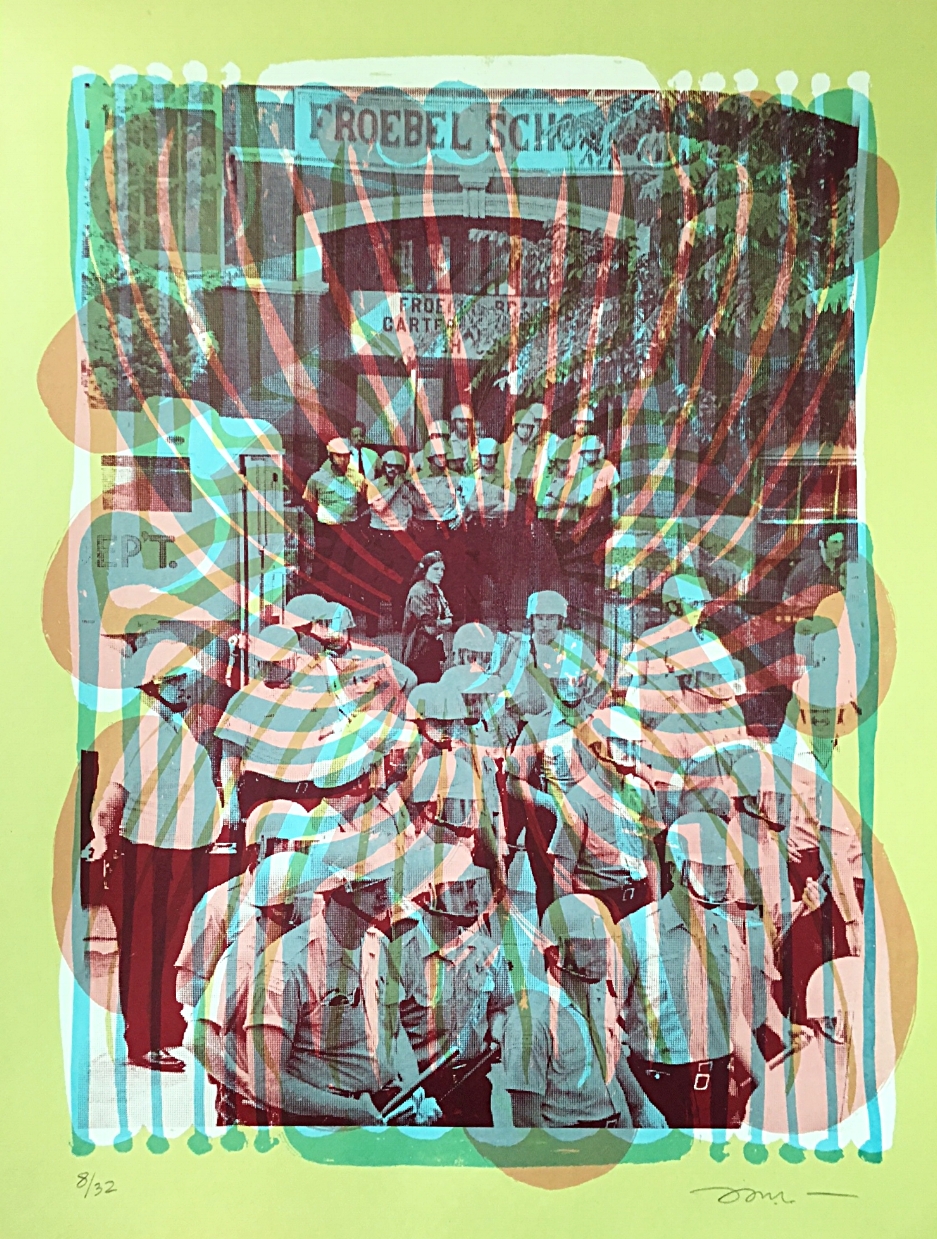

In 1973, the ninth grade branch of Harrison was also the site of a student uprising. The school was called Froebel Branch or Froebel Extension, at Damen and 21st, and it was primarily Mexican and Mexican-American students.

These student resistance efforts, combined with community and teacher efforts, are credited for the decision by Richard J. Daley to support the construction of a new neighborhood high school in Pilsen — Benito Juarez Community Academy High School, [which] opened in 1977. Froebel was demolished in 1978 and Harrison was converted to an elementary school in 1984.

GR: Can you talk about your work at Benito Juarez and how you came into that?

NM: Any kind of good collaboration in schools comes from a good relationship with the teacher, and I have, and have had, a really great relationship with Paulina Camacho, the teacher there. She’s a great artist, just a great thinker and inspiring to work with. I also knew that she had a fantastic relationship with her students, and she brought me in and all these other artists. I mean, I knew her students were one hundred percent on board with her for a reason, because they really knew they could trust her and that she was getting into some stuff that she was connected to. And I never had Mexican or Mexican-American teachers, and I never had Mexican-American female teachers, ever. Paulina’s graduate thesis was entirely about palimpsest and space and power. She’s from Little Village, so she was thinking about people’s experience in these highly-charged spaces. And I’ve always been trying to resituate the borderlands here, you know, because it feels the same to me — that tension, that push and pull of belonging or not belonging.

I came in with Bianca Diaz based on this comic she did when she was working with incarcerated mothers. And we were talking about fear and secrets and being able to make art about things that nobody needs to know about. It was about the unknown, in a lot of ways. So people were making this work, and then covering it up using ballpoint pens on notebook paper. This wasn’t about making any sort of representational art, and what it’s going to represent to you is gonna have this other kind of meaning. It’s sort of like a pinnacle in teaching to have the students drive inquiry completely. I’ve developed my relationship with [students] over the years through different classes. And part of the point of my project as a researcher was to be there with [students] and ask them, as the primary stakeholders in this history, what this history meant to them and what questions I should be asking, so the inquiry would come from them. So I would develop a relationship with students so they could say ‘no that [topic] is boring’ or ‘I wasn’t interested in this’, so that I could then take that information and continue to refine and sharpen what we were working on. But it always starts with an exercise using primary sources, and I’ve gotten all of this visual culture, all of this material.

GR: What kind of reactions or dialogues has it generated with your students, especially when they’re looking at those histories of the protests from ’68 and ’73? Because some of the protests in ’73 had also partly led to the creation of Benito Juarez, right? So there’s a connection there.

NM: Uh huh, yeah and there was a connection from ’68 too because some of the leadership that was fighting then, like Rudy Lozano was in the ’68 walkout, and Lupe Lozano was there, a bunch of student leaders were there. There were members of MARCH, the Movimento Artistico Chicano, and there were Brown Berets that were at the school board meetings that were leading up to the Froebel walkouts.

GR: When your students see this stuff today and you talk about it in the classroom, are they feeling inspired or is it pushing them in some way?

NM: From day one, students were like ‘I can’t believe this story isn’t being told. Why?’ And I was like ‘yeah, why…?’ And I was like ‘this is your life. This is you.’ This is all about the fight for this school. And, you know, there were police officers that infiltrated the student movement, and I asked them ‘would you know if one of you was a police officer?’, and they were like ‘whoa….’ [makes surprised face]. The other thing that got them very excited is that there’s so much more to know.

They were really excited about the site, like they went to the place where Froebel used to be, with one of my giant pictures of the uprising. And then they were like ‘we’re gonna do this performance piece with the video, and we’re gonna light it on fire’, but they couldn’t get it to catch, so they poured perfume on it so it would ignite better. By then the neighbors were watching, and they wrote a letter to the alderman saying ‘stop that Voodoo shit’ — who then wrote to the principal and it came to us, and I was like ‘oh God no!’ So the alderman already fucking hates me. [laughter]

But the fact is, we just are generating so much material that honing in on one photo, and having people work off of it, we could’ve done that. Or having people just work on narrative, or having people just work with the aesthetics. And people wanted to go interview folks, but I couldn’t arrange stuff at the time, and I couldn’t feel safe about sending students out [into people’s homes], necessarily. We’ve spent a lot of time looking at pictures of the [Froebel and Harrison] students who led this work, and then looking at grainy photos from microfilm and dissertations, just studying them and trying to understand them.

GR: Can I pivot us to talk about the specific work that’s in the Hull-House exhibition — obviously the main part of it being the students’ ceramic work. Can you talk about your contribution to that show?

NM: I’m interested in the importance of Hull-House to Mexicans in Chicago. I can’t not think about it and the relationship of all immigrant groups especially to the South and Southwest sides — and the impact that Hull-House programs have had. I thought I knew a lot about them, but then being part of this project just totally blew my mind. For me, I like to get down to the root and hone in on it as much as I can, and I had found some pictures from Cahokia mounds, the largest pyramid structures in all of the Americas, right? And thinking about what I know about the relationship of people in Mexico, and central Mexico, with people in the Ohio River Valley — [for example] there’s actual minerals that are only found in the Ohio River Valley that were also found in the four corners in Tenochtitlan, in the pyramids in Mexico City. I mean, there was known trade. So I like to think about the migration of people, of pollen, seeds, everything in all directions, not just north and south. And I was trying to figure out what was going on at the Hull-House, and what kind of clay they were using in their factory. And I found some pictures from Cahokia of some of the excavated pottery, and all of the colors are exactly the same colors that you see in the Hull-House pottery. Its not a coincidence, right, because stoneware comes out of the earth in this region. So I wanted to see if there was some evidence of the same stoneware — and there’s some broken pieces in the Hull-House archive, so you can get a really clear view of the kind of clay they were using. They were using a couple different kinds of clay, and they had different firing temperatures. So yeah, that lineage.

I’m studying all this clay because I’ve also looked at the Teotihuacan pottery factories and the incense burner factories, and I’m really interested in the way it looks and the way you can press mold all these different parts and just sorta quilt together whatever you want. So I was thinking about the relationship of the material and the meaning, and then the people.

When I was talking to students about belonging and gentrification and all these big issues — but starting really on a micro level talking about researching your house: you’re an expert, you live there, go look at it. How does it look? What can we know about it? And let’s look at zoning, and let’s look at the way our lots are shaped, and let’s look at the materials and what buildings were being built at what time. Even just a basic, beginning architecture discussion, and then having them make the houses.

Part of this was an experiment to see if it would be an effective questioning for them to think about the place where they live for that long, and to see if they were as excited about the possibilities, because I think people from Latin America have another view of space and power and, like, ‘do we belong here?’ And also, non-white people in the U.S. are aware that their “membership status” is always in question, like you know, ‘where are you from? Like, where are your people from?’ And I’m like ‘get the fuck outta here, we’re from here.’ I still get asked that regularly. I think its hard for people to understand that this border is just a concept, and fucking with the people from Central America is just a continuation of this [U.S.] policy of eradicating Native peoples.

GR: How do you see the role of pedagogy relative to what we might call your “art practice”? Because in your work with students, I think you have this really genuine and legitimate conception of what that collaborative relationship is, but it also makes me curious about when you step back and examine everything that you’re doing and working on, how does pedagogy fit?

NM: I can’t see them separately anymore. I have very little interest in my own small studio, closed-off practice. Sometimes I get like ‘oh thank God I have all this time to be in the studio’, and then I’m just, like, not interested. I wanna be out doing projects that take some unbelievable amount of planning and logistics and juggling the free time I don’t have. I mean, its closer to community organizing than it is teaching. I feel like in any good artmaking practice, you know, you have questions, you have things you don’t know, and then the thing that’s gonna represent the thinking emerges. And that’s exactly the way I teach. I’m not delivering information for people to consume.

I think about emergent curriculum, it’s built together with groups. I think it’s collaborative like community muralism. I spend a good deal of time making sure that what I’m working on with people is convincing — not to try to sell them on an ideology, but to make sure its sincere and believable and worth their time. You know, teenagers are super busy, but their ideas are super valuable to me. I’m more interested in their ideas than I’m interested in mine — but I realize that I’ve got this ability to provide this valuable framework, and to create opportunities for thinking, where people can then generate the real substance for the next provocation. And I don’t know if that’s art, or what. But I’m really interested in civil rights, especially civil rights for teens, and looking at youth activism.

GR: Returning for just a minute to the Future Homes work that you’ve done, because some of the stuff at Hull-House is those small ceramic pieces, but that project has gone through multiple forms, right? I’m just curious to hear more about how it’s taken on these different forms, and what kind of conversation or outcomes its generating with the students.

NM: We thought that was just gonna be a two-day project with a couple groups of people — and they were so powerful. We didn’t expect it. There’s something really incredible about making your house, and then seeing a house that’s in another neighborhood, and then seeing them next to each other.

GR: Yeah, it is really powerful to see that array and how its displayed there [at Hull-House]–

NM: –yeah and you see some of those places and you know they’re not by each other. Its like disconnecting site from place, something like that. Its doing some kind of free thinking — and Paulina recognized it immediately, and was excited about it. And being able to put in these references where people have all kinds of meaning imbued — oh, and the fact that some students were displaced out of their houses before their pieces were even out of the kiln. I’m noticing things that are potentials for more discussion, in seeing all of [the pieces] being together there.

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org

Featured Image: Installation view of the Participatory Arts exhibition at Hull-House. In the center of the photo, a large display case shows ceramic houses and other buildings made by Nicole Marroquin’s students at Benito Juarez Community Academy High School. These pieces are surrounded by other shelves containing ceramics from the Hull-House Museum Collection (which originally were made in the Hull-House Kilns), as well as various commercial ceramics (such as Fiesta dinnerware) and examples of different uses of ceramics. Photo by Greg Ruffing.

Greg Ruffing is an artist, writer, organizer, and curator working on topics around the production of space at different scales — from the macro level of sociopolitical structures and architecture in the built environment, down to an emphasis on community, collaboration, and exchange on the interpersonal level. He is the Photography Editor at Sixty Inches From Center.