Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates — through conversations with currently and formerly incarcerated artists — the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

Matt Sopron served 21 years on a wrongful conviction before being exonerated in December 2018. A lifelong Chicago South Sider, Matt creates across a range of mediums, including tattoo work, graffiti, and oil paints. We met up at Dark Water Studio to talk about the journey to his current tattoo apprenticeship, the connections he’s formed with other artists, and how Matt used his artwork to help get himself free.

Michael Fischer: You’re a self-taught artist; you’ve been drawing since you were five or six years old. How did tattooing come into your artistic life?

Matt Sopron: I was always intrigued by tattoos, from seeing some old guys in the neighborhood with them, and then the music I listened to since I was a kid. I listened to metal and punk and stuff like that — a lot of those guys were tattooed. Hanging out in the streets, at first there weren’t a lot of kids with tattoos, but then kids started getting little tattoos. I started tattooing my friends when I was 15, 16 years old.

Basically, I started with needle and thread and probably tattooed half the neighborhood. They’re still some of my best friends, since we were like seven years old to this day — we’re all 49, 50 years old now — that still got tattoos that I hand-poked on them in my basement when we were teenagers.

So I started like that, and then somebody showed up at my house with a homemade prison machine. Somebody’s brother got out of prison or something and showed him how to do it: “Hey, look what I got!” So I tried it a couple times and it was cool, it was harder.

In 1996, when I was out on bond on the case that I ended up going to prison for, I was always drawing. People would say, “Hey, I want a tattoo. Draw this for me, draw this for my friends.” And there was this shop on the north side of Chicago. I guess the owner was like, “Hey, who’s drawing all this?” My brother got a tattoo there and he was like, “My brother.” The owner said, “Man, tell him to come holler at me one of these days.”

So I went there and got a tattoo by this girl that worked there and talked to the owner, and the owner offered me an apprenticeship. I was hyped up so I told the guy, “Hey, I got this case pending” — I didn’t tell him it was a murder case. But I knew I didn’t do it so I’m thinking, “I’m going to beat this, this is ridiculous.” I got arrested like a year later for some shit, they don’t even say I was at the scene of the crime. So I say to the owner, “I got this case pending, but let me get this over with and then I’ll do the apprenticeship.” He was like, “Cool, no problem.” And then I ended up going to prison, so I never followed through on the apprenticeship.

In the county jail, I did a lot of hand-poked tattoos. Just basically lettering and names and stuff like that — symbols. In prison there was guys that were really good, but in a maximum prison you’re stuck in the cell all day. You can’t go into other people’s cells, so if you have a cellie that don’t want to get a tattoo and you got him for three years, you’re not tattooing for three years.

I did do some tattoos in there, but it was sporadic. I wish I could have tattooed more, so I would have came out here and I would have had more practice and experience, even though it’s a lot different still. It’s just a single needle in there; out here, there’s just an array of equipment. But it still would help. I did do some in there, but as I said, not as much as I would have liked to have done. I would have liked to do a lot more.

MF: Back in 2012, a shakedown team took all the art supplies you had in your cell. Is that part of what drove you to focus on working in black and grey so much, which makes up the bulk of your tattoo work these days? Or were you headed in that direction with the black and grey already?

MS: Black and grey was always one of my main influences — probably the main influence. The Chicano style or prison style, it’s all street stuff and I consider myself a street kid. I mean, I grew up in a middle-class household. Whatever path I took, my parents have no blame on them — it was all me! Maybe my mom wouldn’t like hearing me say it, but I was a street kid. I’ve been all over the city; I’ve been in every neighborhood. My influences were a lot of that, plus a lot of the punk rock artwork — real basic, black and grey stuff. And lettering was my love from my graffiti days, ever since I was a kid.

But I started branching out. I had other buddies in prison that were doing oil paintings and acrylics. They knew that I was a really good artist, but I never dabbled in that stuff, so they started pushing me: “Come on, come on, I know you can get it.”

So I did; I started buying supplies, slowly but surely. I got pretty good at it — never mastered it or anything, but I loved it. I started doing a lot of oil painting. I had hundreds of acrylics and oil paints. I literally had a couple thousand dollars in equipment, so I was doing a lot more than just pencil portraits and pen pieces. I was starting to get away from that, because I’d done that already for years.

I wanted to tackle a new medium, and it seemed like right when I was really getting good, then all of a sudden they came through for a major shakedown. They do that shit all that time. Sometimes there’s an incident that triggers it; sometimes they just do it. They came through and they took everything, from everybody. We’re stuck in a cell, it makes no frickin’ sense. I would put sometimes 10 hours a day into painting and to drawing. Wouldn’t you want guys to do something creative with their time?

It really sucked. I sent everything home. They give you the option to send everything home and it was a couple thousand dollars’ worth of stuff there, so I’m sending it home. Oil paint, one tube could cost you 70 bucks, 40 bucks. I don’t think there’s any less than $10. You can get acrylics for like a dollar, but I sent all that stuff home and I still got some of it at the house.

Then the prison started selling their own art supplies on the commissary. We used to order them from a magazine, from Dick Blick. Now they started selling it at the commissary, but it was like the worst crap ever, so I was like, “Screw this.” I was already doing portraits, but then I just really started kicking it into high gear with portraits. I did thousands. I probably got 500 at the house right now. I would just go through magazines: every celebrity, any face that just caught me or was a new challenge, I’d just boom, boom, boom.

I was knocking them out. I was knocking out portraits every day. Guys in there would want to pay me to do portraits for their grandma or whatever. I would do that once in a while, but I quit doing that because it was a pain in the ass, and I wanted to do what I wanted to do. I wanted to fill my portfolio with stuff that I was into. I had a life sentence but I was always like, “I’m getting out. I want to build my portfolio and I want to have all this stuff. I want to just do better pieces and better pieces.” That’s what I did, and I still got hundreds at the house right now.

MF: Speaking of portraits: you made at least a couple heartbreaking self-portraits while you were in prison. Some people might think of prison as an obvious place to take a good long look at yourself, but I think the opposite is often true. I think for a lot of folks it’s too difficult, emotionally, to even go there and look at yourself in that kind of sustained way. Can you describe the emotional experience of self-portraiture in prison, and doing these pieces?

MS: Well first of all, self-portraits are hard as hell because you’re like…it’s you. You’re like, “Oh no, my chin isn’t that cool.” They’re hard. I did quite a few over the years. There’s one that I called “I Am Edmond Dantès” from the book Count of Monte Cristo. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that, where he crawled his way out. I read that book and I loved it. Then years later I saw V for Vendetta, and he was inspired by Edmond Dantès. At the end when they were like, “Who is that?” and Natalie Portman’s character was like, “That is this, that is that, that is Edmond Dantès,” and she’s like “I am Edmond Dantès.” That’s where I got the inspiration for that.

I seen in a book where someone had a self-portrait tearing through a wall and I was like, “Ah, that’s cool.” I would see other art in tattoo magazines and stuff like that, and you get ideas and you use some stuff, you pick and choose different stuff. But I never want to copy someone’s stuff identically, you know what I mean? Especially if something’s going to be a major piece for me. Because people will be like, “Yeah I’ve seen that, you copied it.” So my version is different from the one that I seen, but I knew I could knock it out, and I just did it like it was through the paper.

My mom was running the Facebook page for me, and through the Wrongful Conviction Network and Prison Reform Network and all these other prisoner networks, we had thousands of followers on my page. I knew that self-portrait was going to tug on the heartstrings and people would dig it. I ended up sending it to this prison art competition and I won first place off it. They got the original, because that was part of the deal: you send it to them and they get to keep the original, and they can sell it or whatever. Somebody’s got me crawling through the paper hanging up in their house or in a drawer somewhere. I wish I had the original though.

You’ve seen the oil painting self-portrait. That’s probably the best oil painting I ever did. That one’s in my mom’s living room right now. I did a few other ones where I was behind the bars. One won me second place or first place too. I couldn’t find a good copy of it when I was sending you pictures, but that one was really good. It shows me behind the bars and then there’s a silhouette of a man and woman on the beach, there’s a hand writing a letter, there’s a woman kind of sad, just different stuff.

Most of the self-portraits I drew, other than the oil painting, all the other ones were thrown in some type of collage — like the one ripping out of the paper. I did them to be impactful, for people to see them and be like, “Oh my god.” I wasn’t like, “Let me draw people in to scam them.” This is what I was feeling at the time and different stuff that I dream about, freedom and going home. But I knew those were emotional pieces and it would grab people. They’re some of my favorite ones.

MF: You used to donate some of the artwork you made inside to nonprofit auctions, for causes like Parole Illinois. Flooding Chicago with your work, and with visual reminders of your absence in the form of billboards, etc., was a huge part of how you and your supporters eventually secured your exoneration. Could you describe how you built that Free Matt Sopron visual wave in the city and the ways it paid off?

MS: After going through years and years and years of the regular appeal process and getting denied and denied and denied…like I said, I was an innocent man and I was just getting so frustrated. I seen other stories on 60 Minutes or CNN where these inmates in other states, they built up these grassroots movements and they used Facebook and they used this and they used that. I seen a guy in Alabama who used a billboard; I seen this guy in Missouri that used Facebook, holding up “Free Ryan Ferguson” signs all over the country and other countries.

So I was taking notes and building my gameplan to get my name out there, to get the recognition out there, and maybe get some media and maybe get someone important to follow me. I seen the West Memphis Three and they were drawing in Johnny Depp and Marilyn Manson and Eddie Vedder. I literally wrote to all those guys; I sent those guys packages of artwork and wrote them letters. I sent letters to the tattoo artists that I really look up to, that reading their interviews I could tell they were socially aware and they seemed like really cool people. Or people from the streets or artists, one’s a world-famous tattoo artist that said he started tattooing in prison when he was young. I started writing all of these people, I started sending all these people my artwork.

Then we started the whole Free Matt movement, and I used my art every chance I got. I did Ernie Banks, the Cub legend. He was one of the first black Cubs, one of the first black players. When they unveiled his statue [at Wrigley Field], I did a portrait of Ernie Banks from like 1956 — it’s a perfect frickin’ portrait. We made like 1,000 copies on cardstock and on the back, it had a sticker: “To see more of this artwork, visit freemattsopron.com.” I designed shirts too. We already had black and white shirts, but I was like, “If you’re going to a Cubs game, you’re going to see either blue or white.” So we made gold shirts to stand out that said “Free Matt Sopron,” that I designed and had a raised fist on them.

My sister and half a dozen of my cousins, they went to Wrigley on Ernie Banks Day with a couple thousand Ernie Banks prints — which you could probably sell for 50 bucks a piece — and just literally passed them out during the whole Ernie Banks ceremony. I’m sure some of them got thrown in the frickin’ gutter, or someone was drunk and sat on theirs. But I’m sure some people went home and looked me up. We had a website with change.org, and that’s what we were trying to do was draw people to the website, and we did.

Then a tattoo convention came to town. I had a portrait of the main character from Sons of Anarchy; one of the main characters from Walking Dead; the main character from Breaking Bad; these were the hot shows at the time. I had like five different of the big shows at the time and I had main character’s portraits. Same thing: my people made a couple thousand copies with the stickers on the back and went to the tattoo conventions. There’s tables where people have their business cards and stuff like that and they put stacks of them on the tables. They passed them out, they walked around, they all wore the shirts, same thing.

Every chance I got, it was all my ideas. I don’t try to toot my horn; People are like, “Oh, your people did so much” — and my people did, my people are the best. But I was in there just brainstorming, and some things just crashed and burned and some stuff worked pretty good. I was like, “Hey, everything counts, I don’t give a shit. We’re on it, we’re on it, we’re gonna be in their frickin’ face until I get out.” And it worked eventually.

It definitely played a part, because people to this day will be like, “You’re the guy with the billboard.” Or people have contacted me and been like, “I’ve got the Ernie Banks!” Since I been out — like a stranger I met at a concert or something, it’s crazy. So yeah, everything helped.

MF: One of your main post-release goals was to open your own tattoo shop, but you’ve said now that you’re out here, you’re content to rent. It always seemed like everyone I knew when I was locked up was fixated on ownership: nobody wanted to work for anybody else, everybody was like, “I gotta own my own construction company!” Whatever it was, they had to own it. That always made perfect sense to me, because you’re coming from a place where you own nothing and you have no control. Can you talk a bit about what was appealing to you about the idea of owning your own shop, and what’s led you to let go of that for now and just say, “I’m good, I’ll rent for the time being and see how things go”?

MS: Well in prison, one thing is you do a lot of dreaming, you know. You do a lot of dreaming, you do a lot of big thinking. You’re not in reality, especially when it comes to the street and being free. So everybody’s gonna get out and date a superstar or own their own business and become a millionaire and all this.

One, it’s just not that easy; you have no clue, just coming out here 21 years later. The world has changed, everything’s changed. You’re not in your twenties no more — I’m gonna be frickin’ 50 years old. So you gotta take baby steps.

You hit it on the head. Everybody in there is gonna own everything: “I’m gonna get my own car wash, I’m gonna get my own barber shop, I’m gonna get this.” And it’s cool to have dreams and goals, but get out and get your feet wet and get established back in the world before you jump out there like that.

I know guys that were exonerated that got $6 million and instantly bought a restaurant downtown, bought a car limo service, and he’s got no money seven years later. Because he didn’t know what the hell he was doing. I apprenticed here [at the tattoo shop] first, and during the apprenticeship they teach you a lot about how to run a shop and how to run a studio. Sitting back and looking it’s like okay, it’s a lot. There’s a lot more to it.

I know other buddies that had shops and their shops folded — and these guys are great artists, so how did the shop fold? Because there’s a lot more to it than just banging out tattoos. I count it a blessing, getting the apprenticeship here. The owner here, Jose Perez Jr., he’s one of the top black and grey artists in America. He’s been super cool with me. He knew my whole story through mutual acquaintances before I even got out, and he helped sell my lettering book at conventions and stuff before. A friend of my brother’s used to work for him when I was away.

I came out here and got a tattoo from him. He hasn’t had an apprenticeship in years, and I got the apprenticeship with him and it’s been super cool. I’m content, I’m cool. I don’t even think about owning. Being still new to the tattoo game, my main focus is every tattoo I want to do better, I want to do better, I want to do better. Owning something, it’s the last thing on my mind right now. Because there are guys that own shops and studios, and they’re trash.

And then seeing what happened when COVID hit, you know? They closed these down for 90 days. I just watched an interview with this guy Paul Booth, who’s one of the most famous tattoo artists in the world. He had six or seven other artists and six or seven employees in New York City, and they shut it down. He closed up and now he’s in New Jersey in a private studio tattooing by himself — and this is one of the most famous guys and probably one of the most expensive tattoo artists in the country. He’s literally tattooed stars and wrestlers and every frickin’ heavy metal band you could think of, and this guy couldn’t keep afloat.

So it’s a lot harder than people think, and COVID…it’s not like that’s a normal thing, but who knows? Maybe it is a normal thing from now on, you know? So it was hard. It was hard here for my boss. Luckily, they kept it going and I’m still here.

MF: One of your goals when you were released was to build on connections you’d already made with free-world artists — people you’d first contacted while you were in prison. You’ve said a little about this already, but is there anything else you wanted to say about how you reached out to make those connections, and how those connections have matured and borne fruit for you now that you’re home?

MS: A lot of people didn’t write back, that’s for sure. But quite a few of the tattoo artists that I really looked up to, they did. One was a guy named Norm. He was a famous lettering tattoo artist and famous graffiti artist and he was opening shops in California and one in Hawaii. I sent him a copy of my book and wrote him a letter. About six months after I got out he passed away, which was pretty sad. The whole tattoo industry, the graffiti community, everybody loved Norm. So that really sucked, because he’s gone and I never got to meet him, never got to get tattooed by him.

A few other artists, one is Tamara Santibañez in New York — I just talked to her yesterday as a matter of fact, she texted me. She’s been a volunteer teaching art at Rikers Island. She’s done projects with prison artwork where she was paying inmates $100 or so for different pieces. For me, reading all this about her, they asked her what her influences were in a magazine and she said prison art, she said lettering, she said graffiti, she said punk rock…I’m like, “That’s me!” She seemed real socially aware and was talking about the prison system and how jacked up it is and I was like, “I gotta get at her.”

She wrote me back and we’ve been friends ever since. She’s been super supportive all the way to the day I got out. That was the first FaceTime I ever did. She was texting me — I follow her page and she was like, “Matt!” this and that, because she knew, she followed my court case. So we’re texting and she hit the button where it popped up for a video and I was like, “What the hell what do I do?”

She’s been really cool and an inspiring and down-to-earth person. Even since I’ve been out, she’s done other projects with prisoners. She’ll contact me to say, “Hey, I’m gonna do this or that, do you know if any of the guys would be interested?” And I’m like, “Hell yeah they will be!” Whether it’s something to get paid for or not get paid for, I know these guys well, you know? I know the right guys that are good artists in there that’ll even donate their art.

There’s a lettering guy in Chicago who’s really good — top lettering guy, famous lettering dude from the street background and everything: Sir Twice. I always looked at his stuff and followed his stuff, especially when I got out, on Instagram. One night I go on my Instagram — and I’ve been following his page and I get a message from him, because I’m always liking his stuff and commenting. And he was like, “Damn homie, I bought your book like 10 years ago when you were in prison. Man, I’m so glad to see you’re out.” And I was like, “Damn. This dude, who I look at as one of the best, he bought my book 10 years ago.” So that was really cool. Since then I met him at conventions and he’s a super cool dude. So that kind of stuff just opens doors.

There’s a community almost, of a lot of the lettering guys that are really cool friends. So some of the guys that Sir Twice messes with, they’re from California and stuff, they’re famous lettering dudes. Really good dudes, really good artists, same type of backgrounds pretty much, how they grew up, like me. Everybody’s been cool. Everybody I meet at the conventions — and like I said, I look up to these guys. They could be like, “Psh, who’s this guy? He just started tattooing.” But they don’t. It’s all “What’s up, homie? Kick it with me while we’re tattooing,” open book, talk about whatever, hit each other up on Instagram here and there.

Crazy thing is, just a couple weeks ago, Sir Twice was in Vegas tattooing, and he was at Norm’s brother’s shop. Norm’s brother has a bunch of Norm’s old stuff, like his collection of books. And Twice was going through the books and he found my lettering book. He opened it up and my letter, this two- or three-page letter, was in the book. He was filming it and he was like, “Damn homie, look, look.”

He sent me the video at like one in the morning, and I look and I’m like, “Is that my fucking writing?” I was like, “Damn. I sent him the book and the letter…he could have thrown the letter out.” But that shows how much of a real dude this was. He kept my letter, and that meant a lot to me. I never got to meet the guy, but Twice seeing this and sending it to me — it was a trip, it was a big-time trip.

A lot of the people I’ve contacted, I’m still in contact with them. And through them I’ve met more tattoo artists, more graffiti artists, just starting to network more. Meeting guys in bands that I looked up to too; I’ve been backstage hanging out with these guys, they’re giving me free stuff. They know my story. They know I’m a tattoo artist, they know I’m an artist, they know I’m a street kid listening to hardcore, listening to punk growing up. And I walk into the venues and one of them sees me, says, “Come on,” takes me right backstage. It’s been a whirlwind, it’s been really cool. I’m living life to the fullest, that’s the way I look at it.

MF: One of your favorite artistic subjects is women. Normally, when I hear that a guy who’s locked up or has been locked up for a long time likes to do portraits of women, it’s like, “Oh shit, here we go.” For people who don’t know: we’re not talking about pin-up style, we’re talking the most graphic depiction of women you could possibly imagine. A lot of these guys are selling it as porn on the cell block, so I get that that’s what’s common in prison artwork. But obviously you’re specifically not doing that. So talk about what’s fulfilling and meaningful to you about how you choose to draw women, and the portraiture you do around women and the female form.

MS: I haven’t drawn too many women since I got out, but inside, probably 80% of my portraits were of women. Some of them were just celebrities that I thought were hot; everyone’s got their top celebrity list. I drew plenty of Salma Hayeks and J-Los and Jennifer Anistons.

But sometimes a face would just catch me from a Revlon ad in Time Magazine or something — just the look, or I just like the one side of her face — and I would rip that picture out and I would save it for when I would do one of my collages. Being influenced by prison art and Chicano art, you do a lot of collages. I would take a lot of these pictures of just random perfume ads or whatever, and if the face caught my attention or even just the eye or the lips, I’d rip ‘em out and I had folders saved with all kinds of stuff that I liked. Then I would use them later on, for references.

I did a lot of Day of the Dead girls, a lot of the girls with the clown makeup, the Chicano-style clown makeup. I drew a lot of different punk rock girls. I’ll take a girl and I’ll put a mohawk on her and tat her all up — and this was some supermodel in some lingerie ad — and just create my own version of this woman, whatever I was feeling at the time.

Yeah, I never drew the…there’s quite a few guys that do draw that stuff, the more sex-related, raunchy shit. I never really drew any of that. I tried to draw them as beautiful as they can be, or classy or elegant. Or the beauty that I was into — could have been a chick with the clown makeup or a chick with “Free Matt” tattooed across her throat with the teardrops and make her look like a punk rock girl, make her look like a girl from the neighborhood: baggy pants and a wife-beater on, tattooed all on her chest, lettering, stuff like that. I loves doing that.

I did the straight up portraits, celebrities and stuff like that, but I also love creating and molding my own versions; I got quite a few of them. If you’re gonna sit there and draw something and look at it all day, you might as well look at a beautiful face, and make this beautiful face just pop. As the hours go on and it’s coming to life and it’s popping, it’s popping, it’s popping, and you’re like, “Oh yeah, I nailed it.” And then some guy three cells down is like, “Hey, can you draw my girl?” I’m like, “Ehh, I’m busy.”

Plus, you’re surrounded by nothing but dudes for years and years and years and years and years. The art is almost like an outlet. And not on some creep shit. It’s just appreciating the beauty of a woman and creating a woman — drawing her. I think that was definitely one of the main things.

MF: Since coming home, you’ve done a number of large-scale paintings, mural stuff, for bars and restaurants. Maybe I’m being too sappy, but it really does feel meaningful that you’ve had these opportunities to literally make your mark on the community through these commissions, after being ripped away from it for so many years. Can you talk about that — about this kind of ironic, amazing thing of you getting to make permanent marks on this community that you were taken away from for so long?

MS: Being a graffiti artist growing up — and being arrested for graffiti quite a few times, and going through hell with graffiti, either by people chasing you or my parents finding my stash or having to bail me out — they hated it. To this day, if I mention stuff, my parents give me a dirty look. But at the same time, it really influenced me and my art and my life, and I’ll never change any of that, as far as the graffiti side. To this day, I love it. If I’m driving on the expressway, I’m rubber-necking graffiti. The kids these days, they’re blowing it up compared to the eighties and the nineties when I was doing it.

One of my old graffiti partners, he passed away. He was one of my best friends, and his little brother was young at the time. So when I got out, somebody introduced me to his little brother. He’s a really good graffiti artist, but he also does a lot of murals, canvases, etc. So he hit me up and said, “Hey, we’re going to do this warehouse in Waukegan.” It was a big giant warehouse that was empty; they turned it into a paintball place or a place for airsoft guns or whatever. They had cars and buses and structures, and it was graffitied already, but they let graffiti artists go there, because it’s supposed to be like urban warfare type. That was the first time I picked up a spray paint can in 25 years, and it was super cool. It was a high. I did a big piece, it says “Vindicated” and it’s kinda like this one tattoo on my arm. It was really cool. And I did a piece for my boy who passed away.

Then from there, an old friend of my brothers who was part owner of a bar in the West Loop, he hit me up and was like, “Me and my partners, we want some paintings on the walls, like a lot of these other joints got.” I went down there and met with them and they told me what they wanted, and I started doing stuff; it was called the Wise Owl. So I did the owl painting and a few other things.

About six months later, they hit me up and now they were doing the big patio out there, so they wanted the whole outside graffitied with all this Chicago-themed stuff. So I grabbed my buddy whose brother passed away and a couple other guys, and we did the whole side of this wall. We had Chris Farley, Jordan, Cubs, Bulls, Chance the Rapper, all Chicago things — the skyline, different stuff, it was really cool. That was the first big project.

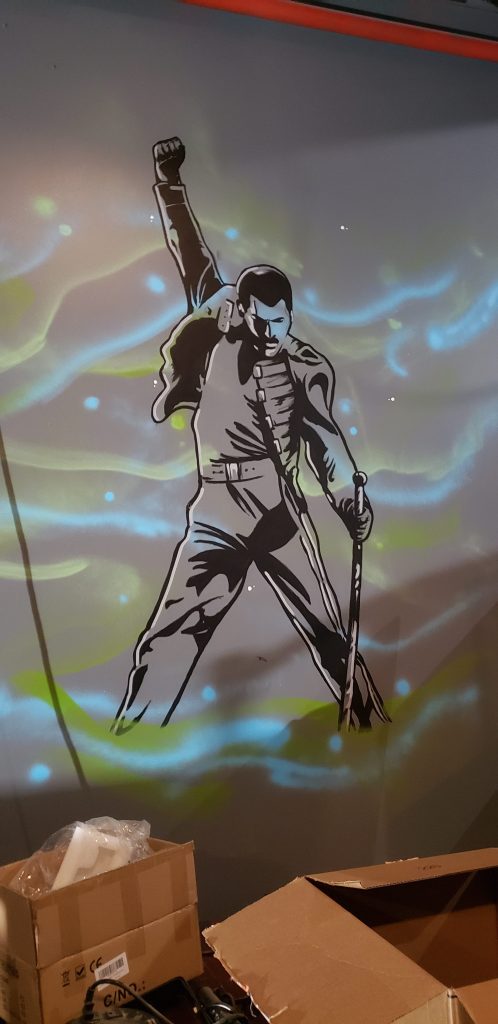

We all posted that work on different social medias, and soon other businesses hit us up. We did a few other businesses. The best one yet was one of the Wise Owl owners was part owner of this place in Joliet where they have concerts, called the Forge. I’d been there for concerts. They wanted this room painted with all these dead icons of the music industry. So three of us — and one of them was my co-defendant that got out, Nick Morfin — we went there, and that piece is awesome. It’s this long narrow room and there’s probably twenty-something five-foot-tall heads or figures of everybody from Aaliyah to Biggie, Tupac, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, John Lennon, Freddie Mercury, people from all different genres of music that have passed away in their twenties. It’s a really cool room and we rocked it; the three of us, we blew that sucker out the park. We got a couple more gigs off of that.

The money’s always pretty good, but mainly it’s fun: you’re hanging out with your buddies and you’re just creating these big-ass pieces. I’ve been to concerts afterwards and I’ll go up to the bar, and down the way someone will say to the bartender, “Oh my god, this room is fucking amazing!” And the bartender will be like, “That’s the guy who painted it right there.” And they’ll say, “What, you painted this?” And I’m like, “Yeah, me and my guys.” They ask what I do and I say, “I do this and I’m a tattoo artist.” Now they want my business card and I give them one of my cards. It’s really cool.

Or just seeing people taking pictures in front of our work. Like I said, I’m big into concerts and into music, into metal and punk and the hardcore scene. To see this place, one of the main places for the shows, and I decorated it, I painted it, and everybody loves it? It’s really cool. I think I got something else lined up pretty soon.

I’m always gonna be down for that. I’m getting the graffiti, but it’s legal! I get to do what I love, but I don’t have to worry about getting chased or getting arrested. I’m gonna have to be really old, with arthritis in my hands before I stop doing stuff like that. I won’t pass that stuff up for sure.

MF: Is there anything else you wanted to talk about or touch on that we didn’t get to?

MS: Since I’ve been out, I’ve designed some shirts. I was contacted by the Northwestern Center on Wrongful Convictions — this was before COVID. They said, “Hey, we’re having this event and we want exonerees that are doing their own business-type stuff.” Maybe this guy’s got a bakery, someone else selling a book or whatever. And they’re like, “You’re an artist, you could bring some of your art, put it on display, you could sell it.” So I said, “Yeah, cool.”

I’ve got hundreds of pieces, and it’s hard to decide which ones I want to sell. I have dreams of when I have my own house with a big man-cave with all my stuff hanging. So I picked a bunch of stuff out and I was like, “You know what? I’m gonna make some shirts.”

Lettering is one of my main specialties that I love, so I made “Vindicated” shirts and another one with “Justice for the Wrongfully Convicted.” I also did one that has a real heart and it has a ribbon going through it that says “Chicago” with the Chicago flag. I brought them to the Northwestern event and sold most of them out — sold a bunch more online and stuff like that.

I’m definitely gonna make another shirt soon; I’m just a procrastinator. That’s another thing too that guys talk about: “I’m gonna sell shirts.” If you have an event like that, it’s one thing. But if you don’t, it’s hard as hell to move stuff. I got a Chicago shirt in mind that I want to hook up. It’s something that I’m gonna do it for the fun of it, not so much to try to make money off it. If I ordered 200 of them and I don’t sell them for a couple years, it’s not a big deal.

As far as art-wise: since I’ve been out I’ve donated art at least four or five times to Parole Illinois, Innocent Demand Justice — to these different groups that are trying to make a change or help guys out in prison, or bring awareness to prison reform or bogus sentencing or the wrongfully convicted.

I don’t ever see myself distancing myself from that community. That’s part of my life; my family was involved in that, doing all this stuff and running around. Now that I’m out here, that’s my job. Just a couple weeks ago they exonerated seven guys in one day, and I was right there at the press conference, standing right in front. I had on my “Justice for the Wrongfully Convicted” shirt, and I talked to Joe Dole a couple days later. Joe called from Stateville and he was like, “Ah, we seen you!” Because there were like 25 exonerees there.

A lot of guys don’t admit shit like this because they’re in prison, but Joe was like, “Dude, you don’t know how much it means for us to see you guys.” I told him there were a few other guys that he knows that weren’t on camera and he was like, “Man, get them fuckers on camera.” He’s like, “You don’t know how much it means. This place buzzed for like two days.” Because here’s 25 guys that we all did time with for 20 years or more, and here they all are together, backing some other guys coming home. He was like, “Keep that shit going. Keep that shit going, and get them other assholes involved because that’s what’s keeping us going. That’s what’s helping us to have faith and keep pushing.” And I was like, “Hell yeah, dude. I told you I’m in this ‘til…”

I’ll be doing that ‘til I’m an old man. People ask, “Are you gonna move out to here, there, or there?” And I’m like, “I’m not moving anywhere.” Maybe down the line I have a Florida home for the winter or something like that, but I’m born and raised Chicago. I’ll be in the Chicagoland area ‘til I die, for sure.

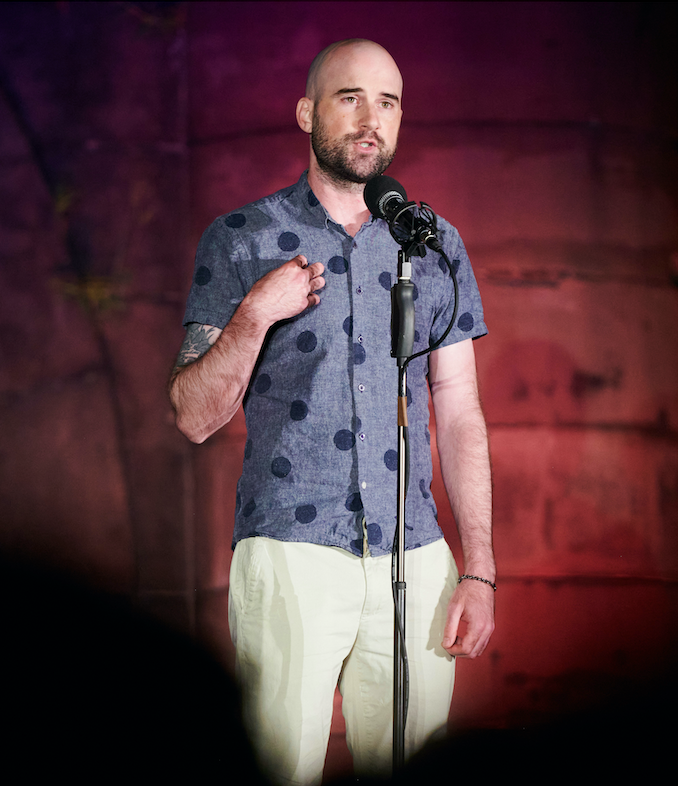

About the Author: Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015 and is currently a humanities instructor in the Odyssey Project, a free college credit program for income-eligible adults. He’s an Illinois Humanities Envisioning Justice commissioned humanist, Luminarts Cultural Foundation fellow, Illinois Arts Council grantee, and a finalist for the PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship. His nonfiction appears in The New York Times, Salon, The Sun, Lit Hub, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and he’s been featured on the Outside Magazine Podcast, The New York Times‘s Modern Love: The Podcast, and The Moth Radio Hour.

About the Photographer: Kristie Kahns is a photographer and art educator based in Chicago. Remaining close to her first passion of dance, she has spent over a decade as part of the Chicago dance community through her camera. She is also a dedicated teaching artist, creating analog photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying art education and administration.