Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates—through conversations with currently and formerly incarcerated artists—the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

In 1994, Patrick Pursley was convicted of a crime he didn’t commit, despite no eyewitness identification, confession, DNA, or fingerprint evidence. Patrick’s case was repeatedly rejected by wrongful conviction advocates, citing the fact that there was no legal recourse to force a re-evaluation of the one piece of evidence—ballistics—that the state had used to convict him. Instead of giving up, Patrick helped write and advocate for an amendment to the Illinois post-conviction forensic testing statute. The amendment passed in 2007, clearing the way for Patrick’s own exoneration—the first post-conviction exoneration based on ballistic testing in the nation.

In addition to being a legendary jailhouse lawyer, Patrick is an author and producer. We met up in Hyde Park to talk about his creative path, the influence of hip-hop on his life and thinking, and his evolution as a man.

Michael Fischer: The writing you’re most known for is your legal writing, but you’re also deeply involved in creative work. Can you talk about where your creative life started?

Patrick Pursley: I was always a creative type. Prior to my incarceration, I had a production company in Rockford. I promoted music, film—I had about ten or fifteen thousand dollars worth of equipment. It really stems from my childhood, drawing Marvel comics. It also stems from the streets: hip-hop, graffiti art, just the culture. I’m very much about the culture of hip-hop.

From a prison perspective, people who draw cards and do paintings and stuff like that, they have their own survival mechanism or hustle in prison. I knew that what I was bringing to the table, to other prisoners, might be a little bit different. I wanted to incorporate their art, but make it message-based. We started with a newsletter, as early as around 1999. That newsletter was called American Prisoner. I always rolled with a gang of artists, writers, jail daddies, litigators—people who thought and wanted to change conditions. The art and the words came together to form that.

MF: Talk about how I Am Kid Culture came about. Who is Kid Culture?

PP: Kid Culture is my brainchild—my creative property. In prison, everyone who creates something feels like their artwork or their idea could be stolen. But I worked in the opposite way; I wasn’t worried about anyone stealing my idea. Like the logo on our cards: it’s a kid doing a breakdance handstand with one hand on top of a globe, with buildings in the background. There’s a lot of symbolism there, in terms of urban culture. It’s so big and corporations are ultimately behind it, but I think kids should be the actual focal point. Not just kids: teens, the whole culture that embraces hip-hop.

I have arrested development, so I still listen to hip-hop. I’m 53 and I listen to hip-hop basically all day. In prison, I didn’t want to feel nothing. I didn’t want to listen to slow music or R&B or any of that. You hear that all day from everyone else. I didn’t want to lament, I wanted to create.

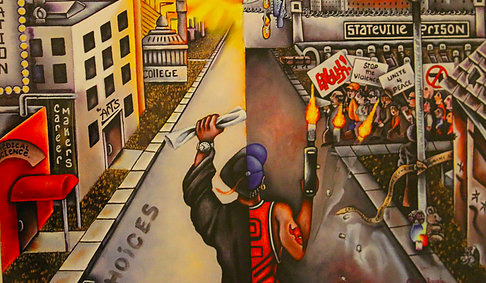

I really got a blessing in the sense that professors were coming into Stateville as volunteers from Loyola, Depaul, and Northwestern, and they brought students. As I was taking these classes under these professors—doing the writing, doing the newsletters—we decided each newsletter would be topical. If I want to talk to a fifteen-year-old about intergenerational incarceration, I’m not going to say, “intergenerational incarceration.” I’m going to say, “Confessions of a Jail Daddy,” because a teenager gets that. They automatically know what I’m talking about. If I want to talk about the dumbing down of America to a teenager, I’m going to say, “Swag versus substance.” So we developed, with each newsletter, a topical point.

Out of the newsletters grew TRUST, a 12-step workbook for at-risk youth and gang members. TRUST stands for “The Rehabilitation of Urban Street Terrorists,” which all gang members are labeled as. I’ve been out of my gang since 1987, but most everyone I know was still affiliated behind bars. The 12-step workbook was based upon the work of a former Black Panther who got into it with the police, shot a cop, and was sent to prison. 20 or 30 years later, he put together four steps based upon finding the parallels between the tribes and street organizations of America and the child soldiers of Liberia. From that, the 12-step workbook grew. I also put together a “hood PTSD” self-styled diagnostic test for teenagers.

All of these things use art to incorporate and to capture the moment and the thought. For a few years, the professors coming into Stateville were taking the curricula out to gang peace circles, high schools, colleges—all these various places. Because of that we were getting responses, and I knew that what we had was good. I knew there was a lot of interest not only in prison but in organizations behind the wall and how they function, conditions of confinement and the like.

I was always pegged as a rebel leader, so I was always put in segregation during hunger strikes and stuff like that. There was a newspaper that picked up one of those hunger strikes: Bay Area News. I was so honored. Eldridge Cleaver and all these people are my heroes, and then here’s me. I believe on some baby level, some very small level, there are 100,000 Malcolm Xs, 100,000 Martin Luther Kings.

We were doing our part, not just to challenge conditions of confinement, educate fellow prisoners and the community, but we also gave back. I did a clothing drive: Hats for the Homeless. The prison guards just laughed and said that no inmate would donate hats or gloves. My fiancé Michelle walked out with about four bags full of hats and gloves. I did a cosmetics drive for a domestic abuse shelter, and then my friend did Arts for Alzheimers because the person who took my idea to Springfield to get the post-conviction ballistics amendment passed, Bill Ryan, his wife died of Alzheimers. I know that during my time at Stateville, I made an impact, whether it was through law, activism, or art.

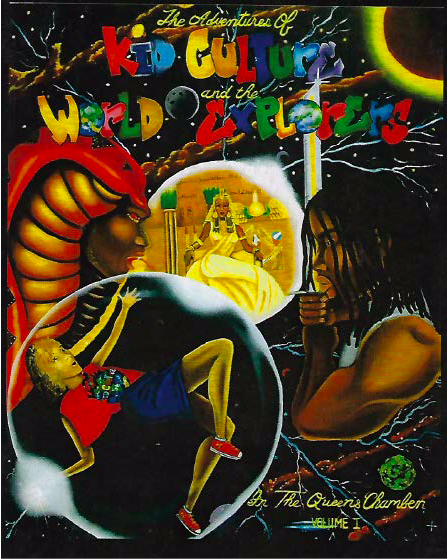

MF: You’re the author of Adventures of Kid Culture and the World Explorers: In the Queens Chamber, Volume I. You’ve described it as an urban version of Harry Potter.

PP: It was an idea that was born before I even got locked up. The origin of the idea, the core principle idea, is that if people knew more about the achievements of cultures other than their own, then perhaps that would reduce social friction and racism. That’s a lofty idea, but that was my idea: cross-cultural curriculum. This was in 1993.

I would say around 2002—this sounds so strange—I had a very surreal dream. Some of the characters in the book literally came to me in that dream. The book series is about at-risk youth whose parents are locked up. Dysfunctional families, living mired in the hood, but they have intrinsic value. From the supernatural side, I created a character based upon an ancient Egyptian who was supposed to combine the 25 dynasties of Egypt.

The other protagonist is the Queen Mother. She’s patterned after Dr. Margaret Burroughs, who started DuSable Museum. Dr. Burroughs and Helen Sinclair would come into prisons even as like 90-year-old women, rest in peace. They had more strength in them—they’re going to Cuba, Africa, Israel. I was so inspired. Largely my inspiration came from the fact that I don’t really have a mom. I’m looking at these maternal figures coming into these prisons, with men who are supposed to be the worst of the worst, and they’re not just ministering to us but treating us humanely.

So the Queen Mother is patterned after Dr. Burroughs. The queen comes from ancient Babylon. Both of these characters are sent to intervene in the lives of at-risk youth, and each book goes to a different culture. There’s almost a crypto-history I’ve put into the series. For example: I challenge the notion, in Book 2, about Christopher Columbus being a hero. I turn it on its head and challenge Columbus Day, right? I use the book as a mechanism—use a fast-paced, hip-hop plot to teach some basics. Like, all guys in jail who are fathers are not dead-beats. That their children have intrinsic value, that they’re mired in these urban hells that are full of PTSD and gun violence. The two protagonist characters, they’re keepers of a place called the Hall of Ancients. It’s basically time travel via a book. You open the book, and you’re whisked away to that era.

The antagonists are a race of shape-shifting serpents who come to you as your brother and sow discord amongst man, and they feed off of negative emotions. It’s a fast-paced series. I’m really looking to do some marketing on it, help get it out there. All things Kid Culture grew out of my original idea for the book.

If each book clicks into a different culture and we have an infinite number of social problems, and then on top of that I could do parallel universes—I could do a lot of different things with it in the future: comic books, film. You saw how big the Black Panther movie smashed. I always felt like if black kids saw more positive, strong images on screen, they would be more inclined to have some pride. With the absence of those characters, I felt like this can be a good series. I think it has infinite possibility.

MF: Do you realize you have an IMDb [Internet Movie Database] page?

PP: Do I? This is part of my dilemma. All of these people have filmed bits and pieces of me, and then I’m not able to get the actual film. Netflix is supposed to call my attorneys but they’re dragging their feet. Another guy, a reporter, said he was going to take a year off to write a book about the case.

My case has more plot twists than M. Night Shyamalan. IAmKidCulture.org is now a 501(c)(3), but there’s also Kid Culture Talent; that’s a LLC. I’m doing this, I’m steady hustling. I know my story is a big story, but I think it needs to bubble and percolate a little.

MF: It seemed like, for a while as your case was pending, you were diving headfirst into creative stuff because you had this manic energy, and you needed to stay busy and move forward. But now that your case is officially over and things have settled a little bit—hopefully—has that changed the pace of your output at all?

PP: No. That’s one of my, some might say, mental disorders. I got exonerated in January 2019. In February I had a spinal infusion surgery that was fucked up and had to have a second surgery. I have a whole host of nerve problems that affect my diet, thyroid, gastrointestinal—everything. I live off of like half a sandwich [a day]. It’s terrible. But the energy does not abate.

People are always like, “Slow down, you just had two spine surgeries!” The best way I can put it is like live-streaming to the universe. My creativity has me working, on average, maybe 10, 12, 14 hours a day still. Sleep is, I guess, something needed. I have a go-until-I-drop mentality. The manic energy is still very intense. A lot of people don’t know how to handle me and just label me outright insane.

After I got that damn gun tested, I thought I was going home scot-free: “Mr. Pursley, we’re sorry.” Nope. They give me a second trial and connected me to some pretrial service. Everyone talks about Meek Mill and probation, but to me the pretrial aspect is just as important and was very onerous to me, very oppressive. First of all, I hadn’t even heard of it. They had the investigative fortitude of Stalin’s Russia. They were all at me. A lot of my manic energy comes from dealing with that and the self-righteous indignation that came with it.

A lot of what I go through in terms of my manic energy, it’s a carryover from prison—a self-defense mechanism. You’re in a cell for so many hours with people who can change very quickly. You’re facing death. Any day of the week, a cop could shoot me while I’m on my toilet. Shoot me in my sleep. Shoot me going to chow. A lot of what I have, this high-level energy, is all connected to that fight-or-flight response that never got turned off.

MF: In terms of identity formation: you’re 53. You’ve been attached to the system, in one way or another, since you were 14. When the time came for you to form an identity, to say fuck the street life and all the ways the system is trying to tell me who I am, what did you turn to in putting that identity together?

PP: I’m born in Elgin. Mom gives me up in 1980. Prior to that, I’m just a suburban kid: smoking bongs, listening to Led Zeppelin and AC/DC, listening to disco and pop music. Later, it becomes house music and street culture and gangbanging.

In prison, I become a jailhouse lawyer. Being a jailhouse lawyer really gave me a good sense of—look, it’s one thing to read Frantz Fanon or Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and it’s another thing to live it. But then it’s an entirely different thing to be able to identify it, articulate it, and push back against it. Most people fall between the cracks and get rolled over by these systems.

When I first went to Stateville, they tried to send me to protective custody. I’m not going to protective custody; I’ve got natural life. No motherfucking way. Eventually the other inmates see that I’m actually an activist, that I actually care about their plight and my plight. I’m an educator—I’m hood law, I teach law and it’s nothing for me. This identity of mine that forms inside is almost like a culmination of all these different parts of my character. I might play Led Zeppelin on the gallery and drive everyone fucking crazy, and not care. I might holler all goddamn day for the guards to let me get my legal boxes while we’re on lockdown.

When I was younger, I was really radical and loud in the most aggressive cell house in Stateville. I would chastise people and say, “Look: the [Chicago] Bulls are not going to be in the law library. The [Chicago] Bears are not going to be in the law library. You’re all hollering for these sports teams that don’t even know you exist.” I knew an artist in there; his name was Ulysses. He sent a painting to Michael Jordan one time. It was like a triple-panel painting of Michael Jordan, and it got sent back. They were like, “We can’t accept this.” I felt like a lot of the distractions people got sidetracked with were unhealthy. I calmed down over the years, but by the time that happened I’d been so verbose and opinionated for so long that I had some infamy with the officers. They come in and say, “We were talking about you last night when we were at the bar.” And I’m like, “Why are you talking about me out in the world? You’re an officer, you have a life.”

I started to see that my words and my thoughts affected my environment. This character that was born for survival also had empathy bred into him from doing guys’ cases and soaking in the inequities of everyone in there, and of course seeing my own inequities. I knew I was not coming out here to do crime or end up back in prison. You might kill me for being a little too active, but I’m not going back down that old road.

Part of that is my dress code. I always wear collared shirts. I’m very conscious of driving while black. One of the reasons why I moved out of Rockford was because the police were parked outside my house when I’d head out to court in the morning, waving to me and my fiancé. That’s a blatant threat. I’m nerdy by nature. I just want to listen to music, smoke a little pot, do my legal writing, make some calls and I’m fine, at the end of the day.

MF: You mentioned arrested development earlier. You’ve said before, “Parts of my personality are still in my 20s.” I have a similar thing; part of me is still 21, because that’s how old I was when I got arrested. How does that arrested development manifest itself for you nowadays?

PP: It’s been three years since I bonded out. In those three years, I’ve probably lived 30 years. But parts of me are never going to grow up. I’m listening to Kendrick Lamar and J Cole. But my precocious child archetype that I’m a little trapped in, that’s what allows me to go back to my projects, to talk to 11-year-olds, to walk the streets and talk to gang members, whatever the case may be. It’s very much part of my vitality. I look at age as relative. Yes, my infrastructure, my spine, the radium in the water at Stateville and all the rest of the pollutants there that destroyed my insides—sure. But because of my almost childlike energy and abundance of creativity, seeing things in this different light—it serves me well through Kid Culture. For me, 25 years ago was yesterday. I remember the day of my arrest like it was yesterday. I remember taking my daughter to a birthday party, stereotypical orange soda with the hot dogs.

I don’t think that’ll ever go away. I just make it work for me. That’s why I’m all over the place, despite my physical problems. I try to stay active and busy, but it’s a challenge. To have parts of your spine replaced and two fucked up surgeries and a torn ligament in my arm. When I came out, I was doing 700 push-ups in 30 minutes and running between sets. Now I’m lucky if I can do 25 push-ups because of my physical limitations. But my energy hasn’t abated. Hip-hop culture is my generation. Even if someone were to say, “You’re too old to listen to rap.” Well, my generation made rap. I’m very cognizant of the way gangster rap has been pushed to the forefront ever since 1987, to where you have a whole generation of young people raised on it. But I’m also old enough to see the cyclical nature of time playing out through hip-hop. You have Kendrick Lamar coming out of Compton and getting a Pulitzer Prize, and yet Compton is the iconic birthplace of gangster rap.

I’m grateful to be in tune with the culture because it carries me. I speak the language and that’s the only way you’re going to be able to approach any teenager. These dividing lines between generations are actually a myth. It’s just a way, in my opinion, for whoever controls the culture to manipulate energy how they wish. I’m going to be able to teach a teenager or even a twenty-something that they have intrinsic value, a gift and a skillset born into them—whether it’s a genetic proclivity or you want to say it’s god-given, that’s your choice.

I tie it back to myself. Prior to me catching this case, I used to dumb it down for the folks: “Yo, wassup?” Whatever. But because of my circumstances, I was forced to evolve or die in there. My grandparents, even though I didn’t know them well, I knew that one had been a doctor, one a teacher, one an electrician, and one a spiritual woman. My one grandmother had gotten me a bookcase when I was a toddler: encyclopedias, dictionaries.

That type of care served me, to be able to navigate the various power structures in prison, whether its gang structures or administrative structures. Fighting your case is one thing, but then there’s just the day-to-day survival. I was always blessed and thankful in there—able to send money to my kids, all of that. My genetic and intellectual inheritance, stretching back to my grandparents, allowed me to save my own life.

MF: You’re a big believer that education is the key, on the inside and on the outside. Are you still planning to attend law school?

PP: Yes. We just DBA’d [our new company] Wrongful Conviction Consultants. I just got my first contract not too long ago. I’m definitely going to law school. My first day on this new contract, I went to appellate court and I knew all the answers, and the judges saw the case exactly how they should. I have a knack for law, standards and review—I survived off of it for so long. In this society, you’re nothing until you’re something. I feel like if I put some letters behind my name, it adds to legacy and it defines how important law was in saving my life. If I didn’t learn law, I would’ve never gotten out; it’s just that simple.

To make law school happen, I’m going to have to sit my ass down. I’m trying to get to a place where the 501(c)(3) can survive on its own. I’m going to start taking online classes, then community college.

I was told by a lawyer and a former prosecutor that it’s not about where you start; it’s where you end. I’d like to end up with a law degree from a nice school. Not necessarily even practice—I have no yearning to practice. The law is full of hypocrisy and bullshit, just like everything else. But it’s my legacy. And it saved my life.

Feature Image: Patrick Pursley looks out the window of a car. He’s wearing a suit, tie, and glasses. Photo courtesy of Patrick Pursley.

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.