Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates — through conversations with currently and formerly incarcerated artists — the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

In 2016, when I began looking for potential interviewees for this series, asking friends for names of formerly incarcerated artists, everyone said the same thing: “I could give you a lot of names, but they’re all still locked up.” This depressing refrain is what led me to expand the scope of the series to both currently and formerly incarcerated artists.

Larry Brent, Jr. was still incarcerated when I first interviewed him in 2017. He was released late the following year, and I’ve been curious ever since to know how he’s been doing. Five years after first meeting each other on the page (and a week before Larry’s wedding!), we finally met in person to talk about what’s changed in his creative life, how his work as a truck driver gives him some of the mental space that’s become increasingly hard to find, and the emotional experience of returning to a city that’s almost unrecognizable.

Michael Fischer: I’m going to start by quoting you back to you, from our last interview. I was asking what you imagined your life looking like when you got out. You said, “I’m more than ready for whatever, and my life on the outside will look whatever way I decide it will. Because I know who I am, and what Larry Brent is supposed to be doing.” Which of course begs the question, now that you’re back on the outside: what is Larry Brent doing?

Larry Brent, Jr.: Basically, everything I planned to do. A little bit of adjustments here and there, because you can write out a plan but nothing’s gonna go according to the plan, so you have to make adjustments. But I didn’t let any setbacks get in the way. That was the mistake I made before, when I was younger. I was always told to do this, to do that: school, work, stuff like that. But I never understood why. Going through what I just went through, I understand why.

The consequences will take you away from everything you’re trying to do. For instance, it can take years to build a career, to be whatever you want to be. Years. It takes only one second to lose everything. Then you’re set back, start all over — sometimes you may not be able to recover. So now I understand why my grandfather went to work every day, why he was a pastor, why he always had rules, why we couldn’t do this, why we had to stay away from those kids, why we couldn’t go into those neighborhoods — I get that now. Now that’s just the way I’m walking, keeping everything very simple and being with the family like I’m supposed to be.

MF: While you were inside, you were keeping your mind active in a lot of ways. You were writing poetry, teaching classes, taking college classes. Other than the artwork, are any of those pursuits still in your life today?

LB: Well, directly, not so much right now. But I’m looking to get back into that. All those things I was doing, I acquired certain tools of self-discipline: how to keep myself focused, how to analyze certain things, how to navigate and how to deal with people. And all those activities I was doing then, I was thinking, “Okay, I’m gonna do this when I get home, I’m gonna do that when I get home.” It wasn’t those activities specifically; it was what I got from being involved with those activities.

I’m still in contact with maybe 20 or 30 guys that were involved with me in different programs. Everybody is basically following the same principles in their own way; it’s just we’re all in different fields that are closely related, still. And we basically all took from the same situation and learned, “Hey man, this is what you need to be doing.” We could do a whole lot more way over here, away from the negative stuff, sticking together, and it was really simple.

Staying out of trouble is a lot easier than we thought it was. It’s a beautiful thing, because you don’t have to worry about a lot of things. You’re living opposite of what you were taught, especially the wrong side of things. It seems easier, it seems fun, but for everything you do there’s a lot of other stuff that comes with it that you have to own up to down the line, and it’s very expensive. Not money-wise (although it can be), but I mean very expensive time out of your life.

I’ve taken lessons away from the Toastmasters thing, which was a lot of leadership situations, a lot of patience, how to analyze things, because I was the Toastmaster president for the last year. I was in the program for two years. The poetry club: how to work with other individuals, how to listen to them, how to create ideas by combining our thoughts together and things like that. I was also an institutional plumber as well, so I learned how to figure things out. I learned how to listen, how to work things out.

If something looks hard, it doesn’t mean it’s impossible; you have to take your time and breathe a little bit and look at it from a different way, and then just push through it. So, not directly have I been doing a lot of those things, but I’ve been using what I learned from them to get through life now.

MF: That was my next question; I was going to ask do you see any of those old pursuits paying off now in emotional ways, practical ways. But that pretty much answers it. You took the skill set, and maybe you’re not giving speeches anywhere, but you still pull out those threads and use those skills in other places.

Last time we spoke, you said, “In isolation, most of life’s distracting entertainment is stripped away.” Now you’re on the outside and obviously distraction is everywhere — we’ve got social media, the 24-hour news cycle. Obviously, prison is not a serene environment in which to create, but it’s a different type of noise out here. How are you dealing with all the new distractions, and are they affecting your artistic practice?

LB: Okay, so you go inside, and you lose everything. The number one thing you lose is control of your own life. You don’t even have control over your own money, when you can see your family — anything. Individuals usually freak out from that, have breakdowns or whatever, immediately after going in, because it’s an abnormal environment compared to the real world.

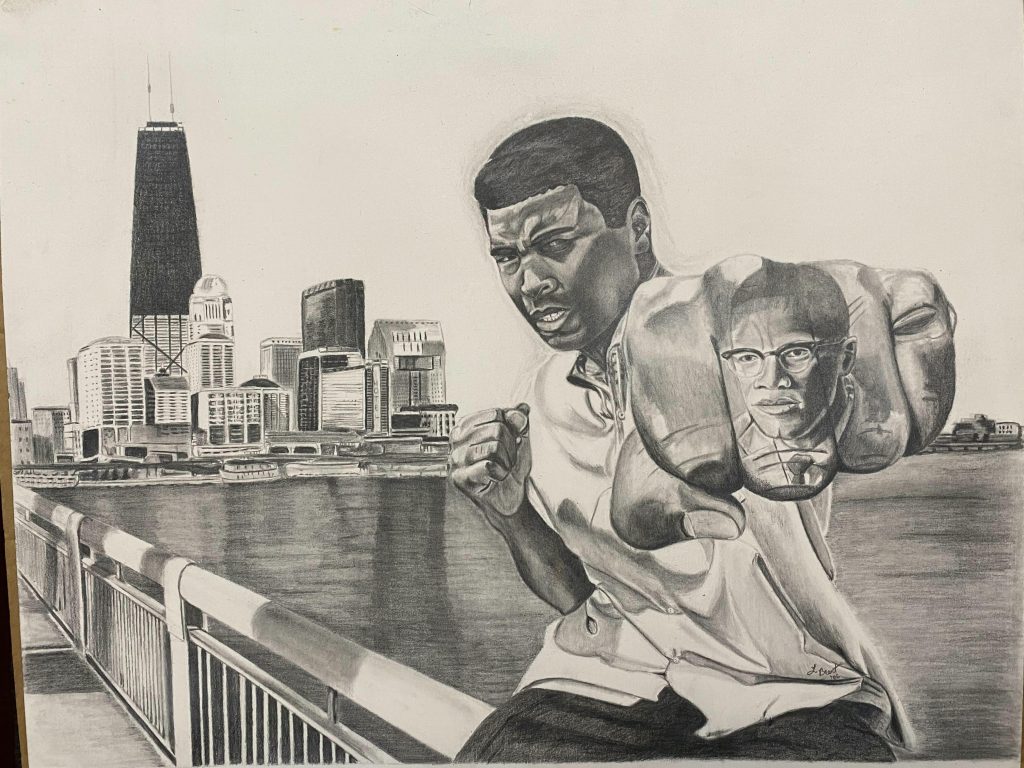

But what I learned was from a lot of studying.

The number one factor guiding me through how to look at it: studying Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. I’ve read about everything most of them people have written. Malcolm X stated that a short period of incarceration can benefit any man, if he has his mind set on what he wants to do. Because you don’t have the distractions in life. There are no late-night parties, there are no football games, basketball games, there are no girlfriends hanging out, no people calling you — you don’t have any of that. You want that stuff, but a lot of time they give people the opportunity to go the wrong way and not do what they’re supposed to do.

So you sit down and you figure out, first of all, how you got to prison. Most people don’t do that. And they think that it is the crime they committed or the act they committed or the people they were with that got them into prison, and that’s never the issue. The issue is — whatever you did at that moment — there were a lot of little, small incidents that led up to you thinking it was okay to do that. It was your thinking that got you into prison, not that act.

Once you sit back and realize, “Okay, I need to correct me.” Most people go in and they blame: it was a girlfriend that did this and my buddy told on me, the police lied on me, or I didn’t have this, my parents didn’t do that. Yeah, all of that could be true, but at the same time it was your thinking. Whether your thinking was something you chose to do or something that just built up from the way you was raised, you still need to correct that.

Once you do that, then you realize okay, you make constant decisions now and you understand why to make these decisions. Sometimes somebody who’s supposed to be your friend…for instance, a lot of these guys that get out of prison are from the streets, and they come home. Their friends approach them: give him a bunch of money, give him some drugs, and give him a gun and a car. Those are not your friends. You think you need that stuff: “Man, I need your car, I need a place to stay, I need some money for some clothes.” But those are not your friends. They just gave you all the tools you need to go back to prison.

LB: But if they just give you a car and money and say, “Hey man, we hope the best for you,” and let you go? Those are friends; the other guys are not. They’re pulling you right back in, because they want you over there with them, because they want to use you again. And most guys don’t see that, thinking because I don’t have anywhere else to go, I gotta go with this. No.

I had a brother come out of prison and he chose to go to a halfway house for a while — because he got out in a different state — to stay away from all that. The parents, the family was ready for him, but he didn’t want to do that. He didn’t want to live in a house with the parents, because he figured he was too grown for that. I told him, “You crazy. We have a family that have houses, we have brothers and sisters that have homes. Go live with somebody that you know you don’t have to worry about.” But he did it his way. He’s still up and down, struggles sometimes, but he hasn’t been back. He’s doing it the way he wants to do it. I respect that.

But being home now, I realize that it’s all about the way I think. I analyze things like a chess player; my father taught us to play chess when we were younger. Every move you make, you think about what’s gonna happen two or three steps down the line, and then you make your decision. Once you get used to doing that, the process becomes quicker; you don’t need a bunch of time, because you may not have that time to make the right decision. It becomes a reflex, doing the right thing. And then from there it’s just practice. That’s it.

MF: And in terms of when you sit down to draw, do things feel noisier out here, when you sit down and try to do something but your phone’s going off, etc.?

LB: Yeah, phone’s going off, my lady’s in the house, she’s talking to me, she’s got questions, she just wants to hang out: “What you doing?” “I’m drawing.” She don’t understand, because I’m used to when I can go in the room and close the door and my guys that I knew in there, they already knew: Larry’s in the room. Don’t even bother. I would go to the day room, sit at the table, people everywhere. I’ve learned to tune that out, and guys see me doing that and nobody would say anything to me.

Unless it’s a new guy who just came in. He sees somebody drawing: “Oh wow, he’s drawing!” He’d come and sit down and say, “Hey man, what you doing?” I just look at him and put my head down and keep doing what I’m doing. He’ll lean over and see what I’m doing and somebody come to him, one of my buddies tap him on the shoulder, and he’ll look up and he’ll get up and I see him leave. He come up to me later and say, “Hey man, listen: I apologize, I didn’t understand.” My friends told him, “Man, leave him alone, for real.” I wait a while, I give him time to figure it out, and if he doesn’t figure it out I would be very direct. I would just say, “Leave.”

It might be rude, but at that time, because I’m actually aggravated — and other than being vulgar about it, which I don’t want to be — I will calm down and it still comes across intense, because that’s the moment that I’m in. But I just say, “Man, leave.” And then they’ll figure it out down the line, and I’ll apologize to him later, but for right now, I need my space to be my space.

At home it’s different. I can’t talk to my lady like that. I can’t decline my mother’s phone call, my father’s phone call, so I’ll take the call: “Hey what’s going on, what you doing?” “I’m drawing, I’m working.” “Okay, cool. I’m not gonna bother you.” But then it’s “yadda yadda yadda yadda yadda yadda” anyway. So it’s an adjustment.

I have to steal free time, and now sometimes to my lady I say, “Hey, I got something to do all day Saturday, so I’ll be moving around.” “Okay, well what you gotta do?” “I got some stuff to do.” I can’t run through everything, because in the course of a day I might have to improvise, stuff’s changing.

She says, “Okay, I ain’t gonna bother you.” Then she’ll call me or she’ll text. We’re gonna have to get used to some things; sometimes I need space because that’s what I’m used to, not being bothered by anybody. That’s the comfort that you had in prison. In life, in the streets, you can’t do that, when you got family and friends and responsibilities. But it’s cool.

Now I have to sit down sometimes and just tell her, “I need to draw” — half-hour of time. She understands, she goes upstairs. I can’t just sit down and expect her to figure that out. I have to say this to her, because this is an adjustment for her as well, to figure out. So it does feel weird to have to work to get myself back into that space, that zone, that headspace — turn on some music or whatever.

Now or later, I’m gonna have to get me some old headphones, because I’m used to putting on headphones and that completely kills everything. Because for now I got the music playing but I can still hear something going on in the gangway next door, police car drives past, anything. She might do something upstairs, drop something, and I hear that and it can pull me out.

LB: It’s a challenge, but I appreciate it. After the wedding and some other stuff that I got going on, I’m definitely gonna have my selected time to draw and get back into teaching classes, because I want to do video stuff to where I do instructional classes on video and post that kind of thing, and have in-person classes as well. I would have the time to do that.

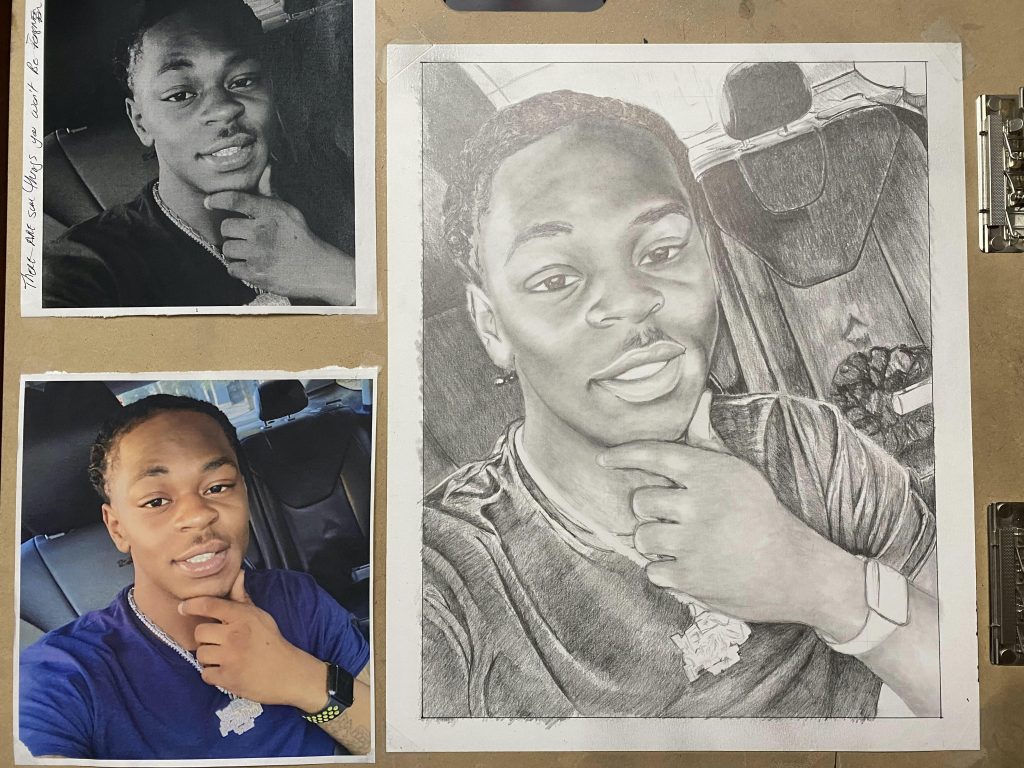

MF: Art has always been a family affair for you, but now it’s literally a family business; you, your sister Liz, and your father Larry, Sr. run an art shop called BrentArt. You’ve cited the ongoing dialogue you have with your father as a key source of creative insight for you, going back years. Can you talk about finally getting to be physically a part of this artistic lineage in your family — to have these artists all together under one roof, essentially?

LB: Initially, it was fun and strange because of being home, of course. And then sitting down we had a few meetings — my father wanted to have a meeting since I got home: me, him, and my sister — about the ideas and things like that. It’s been really cool, because always with him I can call home for an idea or something like that, and he’ll always say something that sparks an idea or a sense of motivation, inspiration.

One thing my father always said about art is that if you can see it, you can draw it or you can do it. Me, I was always doing portrait art: I look at a picture, recreate it for somebody, maybe change a little here and there. Or I look at a couple pictures and put images together, create stuff like that.

But that’s not what he was talking about, because his stuff always came out of his head. He would have a dream or something and wake up, and the next morning he’s painting, or he would always draw with an ink pen. Next morning, he’s drawing something and I’m looking around for the picture, where it came from. He had a dream, or he had an idea, or something popped into his head, or he heard a song, something came into his head.

He’s also a musician, so he gets a lot of ideas from his old music stuff he used to play. My brother bought him a bass guitar a few years ago for his birthday, and sometimes he’ll go and mess around with that and something comes up and he’ll start drawing something from that.

When he said, “If you can see it, you can draw it,” he means whatever you see, period, whether it’s in your head or whether it’s in your eyesight. I took a lot from that. Sometimes I get an image in my head, just a squiggly smudge or something like that, but I’ll know what it is and, down the line, it’ll end up coming to be helpful in something else. I just scratch it down and date it and sign it and put it aside.

Now what I do, now that my lady is here, I had to catch her a few times. I come back looking for it and I’ll say, “Hey, I had some paper, some scratch paper.” “Oh, I threw it in the garbage.” “What?” “Well, you should add some lines to those drawings.” I say, “Where’s the garbage, did you take it out yet?” She says no. I go in the garbage, I pull it out — she don’t understand. I lay it out again and I put a sign next to all of it that says, “Don’t Touch.” And then down the line, I end up putting some things together and she says, “Ohh, I see it, I see it.” If it’s on my drawing table and I have it here, I put it here; I don’t want it in the garbage.

But the artist process is strange for everybody. Being able to talk to my family, we consulted each other a lot of times. When I first got home, me and my sister Liz did a painting together, because the client wanted it to be in acrylic paint. I don’t use acrylic. I’m either graphite, ink pen, or oil. Acrylic is a headache; it dries too fast. So I did the basic stuff: the setting up, forming the shadows, the color scheme, stuff like that. Then she would come in and finish it off and blend everything together, and it was really cool to do that.

My father’s kind of slowing down, so he’s not as active as he used to be. Liz is busy all over the place on the internet, with Facebook and doing these paint parties. And I’ve just been working to rebuild my life. But we’ve still been consulting with each other.

Liz might call and say, “Hey, I got somebody that wants something done. I can’t do this, can you check it out?” I’ll take care of it, or I might start it out for her. She might just need a sketch started, and I send it to her and she goes, “Ohh, okay now I got it,” and she goes from there. But it’s been cool. We’ve been sharing more ideas than actually doing projects, because of me still rebuilding everything, but I’m getting to the point that I’m getting back to having more time to do that. But for us to be in it together has been really cool and awesome and feels good.

MF: In our last interview you talked about developing the perspective that your art has to say something. I imagine your artistic practice these days is taken up largely by the commissions, but that said: what is the work you’re doing now saying, and how is that different from what your work used to say, when you were locked up?

LB: I guess when I was locked up, I used to see different things — different images, whether it be in a magazine, whether it be on a poster or something, and it would catch my eye. I would get those pictures and put them together and draw something and create something else. And what it’s supposed to say, I don’t know. I just wanted to see if I could make it fit together and then let people figure that out.

Since I’ve been here, I’ve been doing more portrait art, of course, and I have been working on an original piece. But I mainly put some ideas together and just let people figure that out, what they want it to be, like that. Still fun, but the only challenge now is having the time to do that. Where before I could have hours or days to do what I wanted to do, now I don’t have that. I have to steal some time. These three hours I’m gonna do this or do that, if I can get that done without any interruption.

But now, basically I just want my art to say who I am. Any individuals looking at it can tell, because it ain’t so much that I found the message between images, it’s the way you do it. I learned when people were analyzing my art; I learned about my art from listening to people talk about it. They say mine is different from other people’s, because mine is always very detailed, it’s very exact, it’s very clean, things like that.

Some guys’ work is kind of messy or extra loose, and I used to look at that as like, “Okay, that’s not good art. You can’t do this this way or that that way.” But no; whatever his style is, is what his style is. It’s not good or bad. It’s just what it is. So you accept it for what it is and now you can be able to determine his art from her art from his art, because of the way that it is done.

I didn’t realize that I was creating my own style by the way I was doing things, different from everybody else’s — but I was, and that helped a lot. So I put stuff together, I see stuff I like and I put it together and just see how it turns out, and let people basically tell me what they see or what it is when they look at it. I guess from that I got used to doing things a certain kind of way, which I accepted as being my style. I like the detail, I like it exact, I like it clean, and I like it to be eye-catching to where it might help somebody else get an idea about something.

A lot of times people come up with stuff or a description of my artwork that I never even considered. But that’s what art is for me. It’s different for everybody.

MF: A lot of creative people talk about time spent walking or driving, time that they get in these solitary moments, as key to their process; they’re alone, they’re out for a walk, they come up with their new ideas. When you’re driving the truck, does that have any of that meditative, generative quality for your artistic practice?

LB: Yeah, all the time, but mostly in the form of writing. Like with poetry: I get an idea, I hear a line or a statement or something like that. I listen to a song, something comes up. The problem is, I can’t write when I’m driving, I can’t stop, I can’t reach for anything. Sometimes I’ll use my phone and put it on video and record my voice saying something and write it down later, but sometimes I forget to write it down. So while it does offer me opportunities to think and get my ideas and stuff to pop up, I don’t always get the chance to retain it.

LB: But it does happen, so it lets me know the process or the inspiration is still there. It’s just that when I sit myself down, when I get the chance to do that long enough, I can hone in on it and utilize it and put it together, stuff like that. Again, in the coming days when I get more of my personal time back, I’ll be able to really put stuff together and focus more on being creative.

Sometimes I can be doing a drawing, and an idea for a poem will come to mind; I’ll stop drawing and start writing, and then I’ll stop writing and go back to the drawing. Sometimes my lady has seen me do that, and she just comes and stands there and leans on you, and I work back and forth just fine, but then she wants to ask questions: “Why are you doing that?” I say, “Can I just do it and we’ll talk about it later?” “Well, you don’t have to get an attitude about it.”

She walks away, and now she’s mad all day and now that’s a distraction. But she’s learning though. I guess because most people don’t live with an artist. She had to come to the point, to learn to give the person their space when they’re busy, to just let them be. Talk about it later? No problem with that. But at that moment? Don’t say anything, don’t ask me anything, don’t touch me, all that kinda stuff. Just let me be.

With the driving, I can’t daydream too much. I have to focus on what I’m doing, because you can’t daydream to where you look up and you’re drifting in your lane or you missed the exit and now you gotta come back. But it does come to me all the time when I’m on the road. Especially when I’m going down 65 and there’s a long ride coming up and there’s nothing out there but open land with fields. You have a lot of time for stuff to come, which is cool sometimes. But yeah, things come to me all the time when I’m driving.

MF: When I was looking at our last interview, I saw that you said, “At one point, I allowed the pressures [of prison] to encourage self-destruction. But that has been adjusted: disappointment, anger, heartache, rejection and loneliness are no longer crushing to me. In fact, anger has been my best source of fuel and motivation.” Which makes complete sense, given the situation you were in, but obviously anger as a driver is corrosive. It works but it hurts us, wears us down over time. So, I’m curious: if anger was your best source of motivation back then, what is your best source of motivation now? What’s driving you? What’s your new fuel?

LB: Well, I tell you: actually, anger’s still there, but it hasn’t been corrosive to me to the point of — it’s about how you use it. It’s not necessarily a bad or good thing; it’s just an emotion a person uses. So, I use that to draw, I use that to work out, that was my response to my situation. I wasn’t gonna let the situation just chew me up like a lot of guys do, become institutionalized really easy. That’s a mental lock; once that happens in your brain, you’re pretty much stuck.

My motivation now is for all those people who stood by me — basically my family. I’m owning up to that. I’m the eldest of six, so I’m a big brother. I’m the oldest child of my mother and father, so that’s a responsibility. I have a granddaughter; that’s a responsibility. I have a son that’ll be thirty this year. I’ve been gone most of his life. That’s motivation.

For every job that I got, I’ve had seven doors close in my face. In the first eighteen months I was out, I had seven different jobs. I wasn’t that I was fired from any. I got one job, it was under contract; the contract ended, so I lost that job after four months. I got another company for a couple weeks; they were almost like a sweatshop. I went from there to UPS seasonal driving, package delivery, but that ended. Got with a friend that owned a truck, drove with him for a couple months, but then the pandemic happened so his company kinda slowed down. Then I got with another company, a little bit bigger, he owned a few trucks. I rode with him for six months, but it was like, everything I had was temporary stuff.

The company I’m with now is called Geneva Transport out of Bolingbrook. I’ve been with this company almost two years, and everything has been really cool: W2, above board, healthcare, because that’s the type of stuff I want. I wanted benefits, I wanted a 401k, that’s what I was pushing for. And I finally got it, which is why I’m there.

But the motivation is, before I got this particular job, everybody else just told me no. And all that did was fuel me to push harder. Because other guys feel different ways about maintaining their lifestyles, about having a source of income. And I said no, I’m not gonna go around. Some guys just had to be self-employed in order to make it, because they got tired of doors being closed in their face. And I said no, I’m gonna make them let me through. I’m gonna get these benefits, get this property (because I’m a landlord as well).

I went through all of that and I got a lot of things done that most guys just don’t want to tolerate or have the patience for, but this is why I want to do it: because this is the page I was on before I got locked up. I just got sidetracked. My motivation is everything I know I should have been doing; I’m owning up to it now. Especially the responsibility of showing my family that they did not support me for nothing.

People believing in me is a very strong source of inspiration and motivation. But I still get mad about certain things. If I try to do something and people tell me no, simply because of something that happened in my life almost thirty years ago, I ask the question: who is the same person they are today as they were thirty years ago? Even if it was a bad person, he’s not the same; he’s worse or he’s better, but he’s not the same. Take me on what I’m doing now. Take me on the merits of what I’m doing now, and that’s how I operate. I don’t tell myself no. I let them tell me no, and I make them tell me no again, and then I make them tell me no again, and I just keep going around.

LB: That’s why I’ve gotten everything done to this point. I’m just gonna keep going, I’m gonna find a different way to get it done. If that’s what I want to do, I’m gonna do it. They can hold onto the past, others can hold onto the past if they like. But that’s their choice, not mine. I’m not gonna let that be my reality or my future.

MF: What about in terms of your artistic inspiration? You’re about to get married, you can see your son again. Do you feel like the engine of your creative life has changed at all?

LB: Of course it will. The way I saw things inside to create and write, I see things differently now. I didn’t have a lot of things around me, so I went with what I felt at the time, what I saw. But now, with so much going on, sometimes it can be hard to concentrate, because there’s so much more now in your head, more things going on. You gotta try to pick and analyze and weed out what you want to get right to, because you can start writing something and just be all over the place. Or drawing, and you can get distracted by another thought.

It’s more of a challenge to get focused and stay focused, but it’s not a problem. Because once I get these things ironed out — since January I’ve been going through an eviction process with the building that I own. Actually, the process started in March and just got done in June, so a lot of stress has been lifted. The wedding will be done next week and I’ll be on vacation, the honeymoon, so that stress has lifted. I’m getting more of my focus back and getting more of my time back, more of my money back. That’s gonna allow me to put my mind on other things that I’ve been wanting to do.

So for the most part, life is life. You just gotta find ways to adjust to it and deal with it and navigate it well. If a problem comes up, it’s only a problem because you’ve never seen that situation before. Take a breath, figure out how to deal with it, and keep it moving so it doesn’t sidetrack you, as it did me once before.

A lot of my friends? We was young; we got sidetracked by problems, and instead of just taking our time to analyze them, we got mad or we just walked away or went a different direction all the time. We were supposed to go past that situation and we didn’t. We allowed it to make us go backwards and sideways when no, that’s not how you handle things. You deal with them and you keep moving right through them and you build on top of that. That’s how I’m living now and that’s what I am now.

MF: Is there anything that you wanted to touch on that we didn’t get to?

LB: I was released in December 2018, and it’s been a really crazy process since then. A lot of things coming back. I had to realize that I had to reprogram myself again, because a lot of information that I collected over the years I don’t need anymore. Like when I went in, I forgot a lot of things and I pushed a lot of things out of my mind, because I had to adjust to where I was at. It was an entirely different world from now.

Then when I got home, I run into people and things — and a lot of people I had forgot. They start describing to me how they know me, and I realize that they do know me. So many faces and names I lost track of, because I had to replace a lot of information with new stuff, and now I have to do that again.

Some people didn’t understand that and we had to part ways, because they would say, “Well you’re home now. Let the jail stuff go. Forget about it and keep it moving.” Well, I’ve been in jail 25 years. It’s not gonna go away overnight. I’m still gonna have some stuff, some issues, stuff to work through, things that I might need to do that the average 45-year-old man shouldn’t be getting into. But I need to get that behind me, so just give me some time. For those that couldn’t understand that, I just keep it moving and let them go.

I had to come to grips or come to a certain maturity level in my own time. Because in a lot of ways, people didn’t realize — brothers who got out before me told me this: you still have a lot of thoughts and desires and ideas of that same young guy you were when you came in, because your life had stopped. And you want to do those things now, all the time now, at this age, at 45. But you can’t do certain things anymore, or those things are just gone. You have to figure them out and see it for yourself.

When I was finally home, it was maybe six months before I came into the city. My family had moved to Lansing, Illinois, but I still had family, uncles and aunts, in the city. Nobody wanted me to go to Chicago: “Hey listen, I gotta go.” “No, Chicago’s bad.” “I get all that. But I’m not going to those areas to do anything.”

When I finally came to the city, it blew me out of the water — seeing some of the old places, even seeing my old neighborhood. And I would get these thoughts: “You know what? I wonder what so and so is doing right now. I could stop by and give them a call and see what they’re doing.” And then I’d have to remember: it’s been 25 years. That phone number has changed. As a matter of fact, I don’t even know the phone number anymore. They’re probably not even there anymore.

LB: Then I go on that block and the house is not even there anymore. That was a lot to deal with. Everything is just gone. As time has went on, I get better about it and forget it. But then something happens that reminds me: it’s been 25 years.

I just kept moving; I got out in December, got into CDL [commercial driver’s license] school in March 2019, graduated in May. I’ve been working ever since — going from this job to that job. And then I got my hazmat license, bought me some property, so I’m the landlord of a two-flat unit on the southeast side of Chicago. I’m about to get married and just set up a lot of things: life insurance policies, pensions, got 401k savings. Looking to acquire some other properties. I’ve got younger brothers and sisters that are also property owners and investors and things like that.

Every year for me it’s always a process: doing this this year, doing that next year. The ultimate goal down the line would be to see if I could get a clemency grant. Can’t get back that time, which is the most important thing. But I’m trying to put things back into perspective and back in order, to where I can get other things done, the way I want it.

For anybody else who’s making it through anything: you got to just deal with the situation that falls in front of you. Don’t run away from it; work your way through it. Then on the other side of it, you’ll understand why it was necessary for you to fight through that and not just run away from it or allow it to break you down. If you allow yourself to be broken, it just gets worse.

MF: I’m really intrigued by the emotional impact of going to a physical place that you remember a certain way, and not only is it different but in a lot of ways it’s been completely erased. You go to certain areas, you go see a certain house and it’s gone, it’s flattened, there’s something else. Can you say more about that, what that was like to come back to places that you remember in your mind’s eye exactly how it looked, and now it doesn’t even resemble that space anymore?

LB: When that happens, the first thing that comes to mind is all the memories attached to that area. I grew up on a street where my father’s parents stayed on one side of the street and my mom’s parents stayed on the other side. My mother and father met when they were 10 years old; they’ve been together ever since. So I knew a bunch of family members on both sides of the street, and all the other neighbors were elders that grew up with my grandparents.

I come back now — and I’ve been hearing things over the years, but I come back now and all those houses are vacant lots or empty. Most of the people died. My grandparents moved on, a lot of the elders lived to be in their nineties or late eighties and they died. Other people come in, whether they’re kids or somebody else owns the property, or somebody’s renting it. They’re not taking care of anything, so it looks the complete opposite, and it’s a process sometimes.

A lot of times I’ll be stuck. I’ll just be sitting there. I just sit down and pause for a while and I’m just going over things in my head, what I remember about this area. Like wow, it’s been 25 years. Am I okay, really? Am I gonna make it okay? Because I’ve missed a lot.

Some people get caught up thinking, “Man, I missed out on so much; I have to catch up or I have to make up for it.” That’s a mistake, because you never will. You just end up going down the road that’s gonna send you back to where you came from. Some brothers like going back and forth and starting over again. I don’t know what it is. Maybe it’s a form of being institutionalized, I don’t know. But I never want to go back to that situation.

Going back to those areas and things being different or people just being gone? Sometimes it may cause you to pause and sit still for a little while. It kind of knocks you on your ass when you realize, yeah…. But life goes on, life keeps moving.

About the Author: Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015 and is currently a humanities instructor in the Odyssey Project, a free college credit program for income-eligible adults. He’s an Illinois Humanities Envisioning Justice commissioned humanist, Luminarts Cultural Foundation fellow, Illinois Arts Council grantee, and a finalist for the PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship. His nonfiction appears in The New York Times, Salon, The Sun, Lit Hub, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and he’s been featured on the Outside Magazine Podcast, The New York Times‘s Modern Love: The Podcast, and The Moth Radio Hour.

About the Photographer: Kristie Kahns is a photographer and art educator based in Chicago. Remaining close to her first passion of dance, she has spent over a decade as part of the Chicago dance community through her camera. She is also a dedicated teaching artist, creating analog photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying art education and administration.