Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates—through conversations with currently and formerly incarcerated artists—the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

Joseph Dole is an artist, writer, journalist, jailhouse lawyer, and government watchdog. Incarcerated since 1998, he spent nearly a decade of his life in complete isolation at the notorious Tamms Supermax Prison, before intense pressure led to its closure in 2012. Joe is currently serving life without parole and continues to fight his conviction pro se. He has recently uncovered evidence suppressed by the State.

Joe has written numerous articles, essays, poems, and research papers. Two of his policy proposals were catalysts for Illinois legislation. He has won four PEN America Writing Awards for Prisoners, was selected by Eula Biss as the winner of the 2016 Columbia Journal Winter Contest, and has published two books. His artwork has been exhibited throughout the country and he recently earned his bachelor’s degree, with a depth area in critical carceral-legal studies, through Northeastern Illinois University’s University Without Walls program. Joe is currently incarcerated at Stateville Prison; we spoke by phone.

Michael Fischer: Your journey as an artist started around the time you came across the “End Torture in Illinois” art campaign. Can you talk about that campaign and its effect on you?

Joseph Dole: I was sent to Tamms for knocking out the assistant warden in Menard. Tamms was a supermax prison, and a coalition of people inside Tamms, along with our loved ones and friends and activists outside of Tamms, were trying to get it reformed. Well, we were really trying to get it closed down, but the first step was to try and get some reforms, because conditions were incredibly harsh. We weren’t allowed phone calls for about a decade. We were in Tamms, watching conditions in Guantanamo Bay or the ADX [Florence Supermax] in Colorado and thinking, “Man, we wish we were there.” That’s how bad the conditions in Tamms were.

On the outside, Tamms Year Ten—led by Laurie Jo Reynolds, who kind of spearheaded the campaign, along with artists from Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative—came up with this tactical media campaign. They said, “We’ll take some stencils and we’ll tag up Chicago to raise awareness about Tamms.” Because nobody knew what Tamms was, or knew what the state was doing there—that it’s considered torture. So they had six foot tall stencils in the shape of Illinois and inside it said, “End Torture in Illinois,” with a star where Tamms was at. And they tagged up Chicago with mud using those stencils, especially near tourist sites. So you’d have buses of school kids about to go in a museum, stopping to ask, “What? Torture? Who’s being tortured in Illinois?” Which to me was ironic, because this was a time when Jon Burge was all in the news for torturing false confessions out of people. But it helped Tamms Year Ten on the outside gin up a lot of support and educate the public on what was going on.

So I saw that—I think The Progressive reported on it, and other magazines had reported on it—and it kind of went viral around the city. To get that much attention for a couple dozen people running around Chicago using mud stencils, I thought that was amazing. It was more publicity than we were able to get for anything else.

That got me into following activist art and political art. I got turned onto Banksy and stuff he was doing about the treatment of Palestinians in Israel, or just how he was using stencils in England. That showed me how important a medium it is for activism and education. I started to veer towards that type of work more.

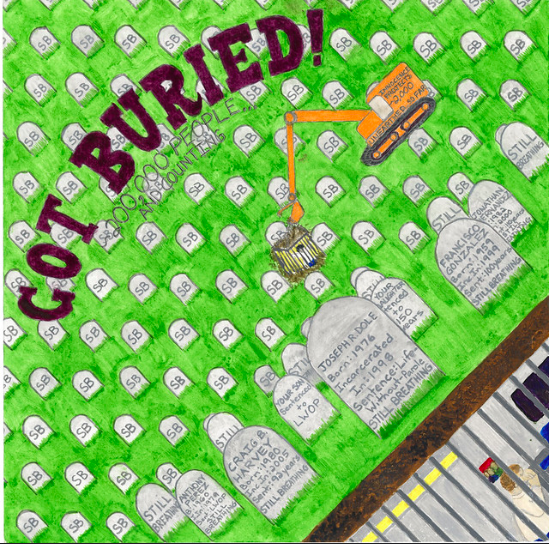

I spend most of my time writing and I’m also a co-founder and basically the director of Parole Illinois, so that takes up most of my time. But when I do have time for artwork, it’s usually doing something to help the campaign or raise awareness about issues in the criminal injustice system. I like photorealism, but I just don’t have time to keep up and get into portraits. But there are a bunch of amazing artists in here who do that type of work, so I try to help promote them—find places where their people can post their stuff online. We just did an art contest for Parole Illinois. We’re going to have an art auction July 26-28 at the Andersonville Galleria in Chicago, and auction off art donated by people in prison, to raise money for Parole Illinois. I think art and activism go hand-in-hand.

MF: Can you talk about what role art and writing played in getting you through your years at Tamms?

JD: While I was there, art wasn’t too big of a thing in my life, as far as me physically creating art. They had no supplies; the only implement we had at Tamms was a rubber pen. There were no paints, no colored pencils, nothing. Some guys used to buy M&M’s and dissolve the food coloring to paint with, but I never did that.

I entered a couple art contests and placed, but I wouldn’t say it was quality art. I placed because of the message, you know? I had a strong message, but that was about it. Out of boredom I was making ornaments and stuff like that. I would send them out to my kids so they could decorate the whole Christmas tree with origami ornaments. But mainly it was writing. When I was out in society I never did much writing, even for school. They’d be like, “Here, read this book and write an essay,” and I’d just never do it.

When I got to Tamms, I’d just been assaulted by a bunch of guards while I was in handcuffs at Menard; they broke my nose, my skull, did some other damage and sent me to Tamms. I had to learn how to write just to learn the law and file the grievance. For a number of reasons, I saw that writing well and being able to articulate yourself and get your point across, writing persuasively, was really important for everything I had to do to protect myself while I was in Tamms. Whether that was writing grievances, working on my case to try and get my freedom and overturn my wrongful conviction, or just raise awareness among the public about the conditions we were living through. So I started writing more and more, started getting a little better at it, and I’ve been off and running ever since.

MF: You’ve spoken before about how not everyone will sit there and read an article, but you can get a strong message across with imagery. Can you talk about how your writing and your art make up two different approaches to the same objective: getting people informed?

JD: You definitely need both for any type of campaign. A lot of legislators won’t even sit down and read much, unless they’re pushing a bill they’ll need to explain to other people. What we’ve learned is that when you go to legislators and want them to support something, what they want is easily digestible, one-page factsheets or something like that.

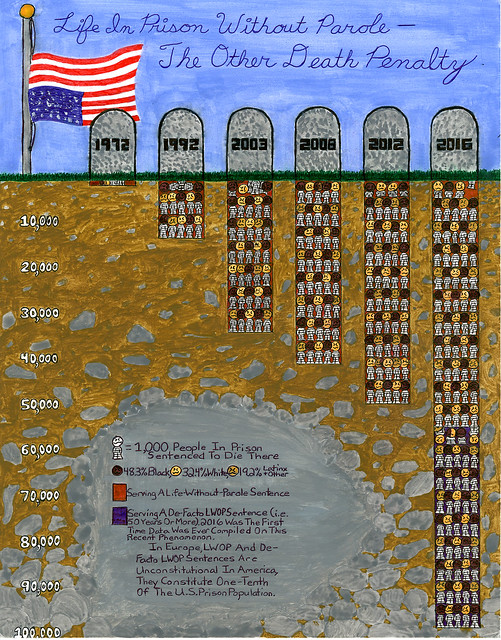

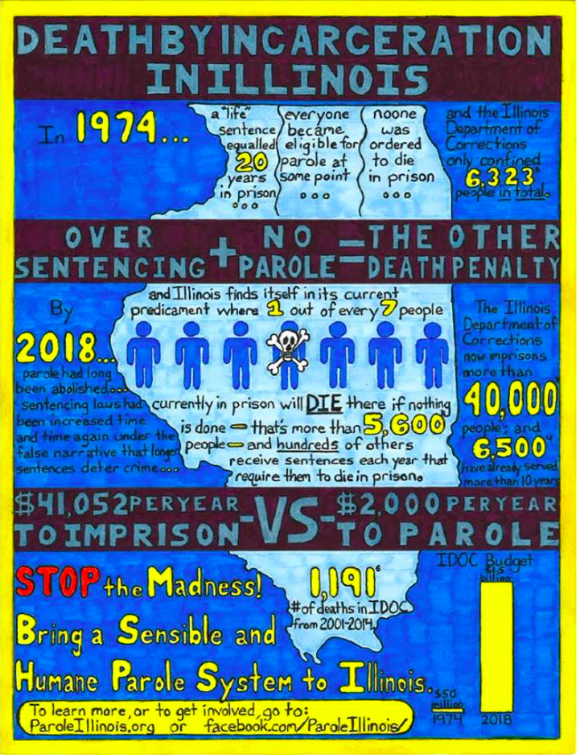

I did a flyer for Parole Illinois called “Death by Incarceration in Illinois.” Stuff like that is much more impactful because you can absorb a lot of information quickly and it’s memorable, and it makes the rounds. If I would’ve written up a two-page essay with all that information and tried to get a bunch of people to see it, it probably wouldn’t have had as much impact. By doing it as an infographic, I can send it around and thousands of people will see it and say, “Did you see this? I didn’t even know all of this stuff.”

A lot of my pieces are mockups that I was planning to do something else with, but people like them so much that they never get turned into the final product—the computer-generated form I’d imagined them getting turned into. When I did the anti-Anita Alvarez campaign mockups, I told people on the outside to tell me if they were okay, and if they said yes I was going to do big poster versions of them. But people liked the mockups so much that they posted those online and they were off and running. About 700 people had already seen that campaign by the time I got word.

Stuff like that makes an impact. It sticks in people’s minds. If I tell you, “Anita Alvarez is protecting cops who kill people,” you might remember that. But if I show you an image of a cop shooting someone and a caricature of Anita Alvarez standing there saying, “Don’t worry, I’ve got your back,” the images make that information more memorable. People want to share stuff like that more than they want to share a lot of text. The people who are best at political cartoons, they realize more people will stop and look at a cartoon for ten seconds and remember everything about it, as opposed to stopping and spending five minutes to read an article about the same thing. The more I see that, the more I want to learn even more about infographics and how to produce really quality political artwork and activist artwork to be more effective.

MF: You were asked by the Anne Frank Center USA to keep a journal while in solitary confinement. You don’t normally like to write about yourself in such a personal way. What was that like for you and are you glad you did it?

JD: I’m glad that I did it. At the time that I was doing it, I had never kept a journal before and I was just starting to find my footing as a writer—to even be able to get a point across. So when they asked me to do it, I appreciated the fact that they were asking me and that I had caught their attention somehow to even be asked.

When you’re in isolation like that, the days were just the same thing over and over again. I really didn’t want to write a “woe is me” type of thing. I wanted to write what it really was like. For those three weeks not a lot happened, but a lot of crazy stuff was happening down there pretty regularly. People were cutting themselves, trying to kill themselves, or killing themselves. Orange Crush was coming in and tearing up our cells, macing people, the commissary guys were messing with people—all types of stuff that I could’ve written about, if those things had occurred during the three-week period that I kept the journal. But those particular three weeks happened to be really mundane. I was like, “No one is going to want to read this, it’s going to be so boring.” But obviously I didn’t want to lie, so I just tried to write down what was happening.

When it was done, I was sure no one was going to read it. Then I sent it in and people liked it; they read it at open forums in New York, and I got a bunch of responses from that. Excerpts ended up being printed in the Mississippi Review, and excerpts were used in the book Hell is a Very Small Place. In here, anything you can do to raise money to support yourself is important and you’re happy to do it. Between contests and the book and other stuff, I’ve probably made enough money to live off of for an entire year in here. So I was definitely glad I did it, particularly once I saw people’s reactions and people started writing me. Maybe people didn’t think it was boring as hell, like I thought.

MF: You were in Katrina Burlet’s debate class at Stateville, the Justice Debate League, which was suspended just weeks after 18 Illinois state legislators attended a public debate class at Stateville in spring of 2018. During that session, prisoners serving life sentences without parole argued for the return of discretionary parole in Illinois. The San Francisco Bay View published your argument from that debate. Burlet has since sued in federal court. Can you talk about debate as another avenue of your activism and the latest on the fight to have debate reinstated at Stateville?

JD: It’s still stagnant right now. In Katrina’s lawsuit, the last thing I heard was that a motion to dismiss was filed and the judge has yet to rule on it. Some of us in here are about to file a suit, addressing all of the retaliation that happened after that public debate—not only killing the debate class and the team, but they’ve also messed with participants’ ability to get into other classes and programs, even messed with our mail. For a while, they were sending all of my packages back and stamping it that I had been paroled. I have two natural life sentences plus sixty years, and I get mail on a daily basis. They knew I wasn’t paroled or released, but they were intentionally fucking with my mail to retaliate against me. That was just a month or two ago that I found out about that.

When journalists try to contact us, the prison withholds their letters until after the journalists publish their pieces, so that we can’t be quoted in the article. The guards have confiscated my allowable property and won’t give it back—a lot of stuff, all because they were upset that we were able to get that many legislators not only to come see us, but also to take us seriously, to the point where they wanted to work on legislation with us.

Anyone who knows anything about prison knows that prisons are in the business of oppression. That’s literally their job. Most people’s concept of keeping people separate from society is physical, but there’s also a lot of suppression of people’s voices, destroying their connections with their families. People in prison are demonized so much that the government feels like they can do anything to us, regardless of what the constitution says or what any rules or laws say, because most of society endorses that behavior. So when I’m back in town talking about how I just treated a bunch of “criminals” like shit, instead of people asking, “Why are you treating people who are in a vulnerable position so poorly?” That’s not the reaction. It’s: “Yeah, that’s great! Give those prisoners what they deserve.” That’s the attitude, and they carry that attitude in here.

So of course the facility tells us no more debate and no more talking to legislators or talk of parole, because they want legislators thinking about prison appropriations, not any of the inmates’ concerns. They didn’t expect any blowback from that; they didn’t expect anyone to say anything. When they kicked Katrina out—who was coming in as a volunteer, out of the kindness of her heart—they expected her to just slink away quietly and beg to be let back in, like most volunteers do. And instead she was like, “No, this is wrong.” And she took it to the media and fought back, which surprised the hell out of the IDOC.

MF: You’re the director of Parole Illinois, as you mentioned. Where does that fight stand right now and what are the biggest takeaways you want people to know?

JD: For an organization that just started out and chose to pick the biggest possible fight—because we’re arguing that everyone should get a chance to prove that they are no longer a threat to society and deserve to be considered for parole, which no other organization will do. Everyone else is more or less going after the low-hanging fruit. A handful of guys in prison and a handful of amazing people out on the streets have been able to really build something concrete, and now we have hundreds of people behind these walls who want to get involved and hundreds of people on the streets who want to get involved.

I think we’re helping to shape the dialogue with a lot of issues around prison, and for a long time Illinois didn’t have that. Even people who were working on prison reform would just do what they felt was possible, without building any grassroots movement and without really considering the positions or the thoughts or input of people behind the wall. They didn’t really take us seriously as activists or scholars. It used to feel like, “We’ll do this for them,” instead of “We’ll do this with them.”

I think the last couple of years, what’s come out of Stateville specifically is that more people on the streets, before they work on stuff, they want our input and opinions, and they want our help in crafting the message and the battle plan. I think Parole Illinois is doing a really good job of being our voice in this fight. Even amongst a lot of our supporters, we used to be kind of voiceless. They would argue on our behalf, but now it’s actually our voice that’s being carried out there, and our artwork that they’re using—or our white papers and policy papers, or even actual legislation that’s being pushed. I think that was long overdue. I’m happy to give my blood, sweat, and tears to continuing that and trying to push it forward, trying to build it up more and more to make us more of a political force out there, so that it’s not so easy to pass laws that discriminate against us, demonize us, take away our rights or abuse us.

For years, you could pass anything. Like the murder registry bill: completely unnecessary, has no utility, but it passed with only one legislator saying, “I’m voting against this because it’s a slippery slope.” You could put up anything that was anti-prisoner or added harsher penalties in sentencing, and it would just sail through the legislature without any thought for how it would affect people’s lives. Not even people in prison necessarily, but our families and our friends, people whose schools are being closed in their neighborhoods because so much money is being diverted to demonize people and keep them in prison. We definitely need a louder voice to become a more potent political force to combat some of that.

MF: Lastly, in [May 2019] you’ll be one of the first incarcerated students in Illinois to receive a college diploma in decades, when you graduate with a bachelor’s degree from NEIU’s University Without Walls program. You’ve been tirelessly educating yourself for so long, taking correspondence courses when you can and then having to stop when the funding ran out. You’ve taught yourself to read in Spanish, Italian, and French. Talk about this achievement.

JD: It’s great, but ultimately it’s just a piece of paper, unless I ever get my freedom back. It helps me to have a little more credibility because now I do have that credential. As far as the graduation itself: the administration here is trying to make the graduation as minimal as possible, and they’re fighting us on every aspect of it. Every time we go to class, they tell us something that’s being done to try and diminish the celebration we’re trying to have. Some of us hardly even want to show up at this point. We don’t even know if they’re going to let us stay to see Chance the Rapper.

It’s good to graduate, but without my freedom it just doesn’t feel like something that I can rejoice about. I used to think, “Oh, I just want to graduate. I want a degree.” But now that I’m actually getting it, I’m thinking about what the next steps actually are. Education’s main practical use in prison is to show evidence to a court or a parole board that a person has grown and matured and is capable of providing for themselves if they get out. But for a guy with two natural life sentences plus sixty years, even though I’m wrongfully convicted, it’s possible that piece of paper might never do much for me, if I never get out.

Joe and the other graduates were ultimately allowed to attend Chance the Rapper’s performance at the Stateville graduation. To learn more about the efforts of Parole Illinois, visit https://paroleillinois.org.

Featured Image: An illustrated portrait of Joseph Dole standing on the sidewalk in an urban streetscape. He is wearing a green shirt and looking toward the viewer. Illustration by Gretchen Hasse.

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.