Several years back when I was torn between interests in archives and contemporary art conservation, I came across the concept of fugitive media, or materials that were not built to stand the test of time and are prone to decomposition or fading. The use of fugitive media when creating something can inevitably render that object ephemeral, causing it to transform or disappear over time.

A close cousin of that concept is the idea of making something ephemeral-by-design, which adds a layer of intentionality to an object or artwork’s creation through the materials used. As the term suggests, when artists create something that’s ephemeral-by-design, it’s a strategic decision to make the work fleeting, potentially adding a layer of meaning or metaphor to any interpretation. Our read of an artwork can shift substantially through this aim alone.

Oscillating between all of these possibilities sits the musings of Sampada Aranke. Sampada is a scholar of performance studies, writer, curator, and professor who is currently leading courses like Afropessimist Aesthetics and Mean Moms and Other Feminist Strategies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Across her practice, Sampada asks questions of ephemerality and intention when it comes to objects of protest or materials and movements of the body, which includes everything from print media created for and by the Black Panther Party to the materials that make up and are emitted from the bodies of women and Black people.

In her upcoming book, tentatively titled Death’s Futurity: The Visual Culture of Death in Black Radical Politics, Sampada is using the stories of Fred Hampton, Bobby Hutton, and George Jackson to better understand images of death during the height of the Black Power movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s alongside the protest signs, posters, and materials that circulated around those monumentally tragic moments in history.

In “Feel Me?” at Iceberg Projects, her most recent curatorial project, Sampada brought together the work of West Coast artists Sadie Barnette, Xandra Ibarra, Dylan Mira, Kristan Kennedy, and Tina Takemoto. The show offers a feminist lens through which to consider how traces of body and bodily materials that are so inherently personal and, in some cases, quiet in nature can manifest in social settings and provoke new, booming awarenesses.

While sitting in the gallery of Iceberg Projects and with Xandra Ibarra’s Menstrual Rorschach Interpretation whispering quietly in the background, Sampada and I spoke about her current work, reading the colonized body and Western Enlightenment through a feminist lens, and what it means to be in and not of the institutions of academia.

Tempestt Hazel: We’re standing in the show “Feel Me?” at Iceberg Projects, but I actually don’t want to start our conversation with talking about the show. I’m really interested in some of the things you talk about as being centered in your work—especially things like the visual culture of death, specifically the death of Black people, and things that I think so many of us are questioning, dismantling, interrogating, reinforcing, and creating work around in real-time. I’m curious what it’s like to be a scholar and a curator who is doing work at a time when things are happening so quickly all around you. Art historians, by definition, tend to think of the past, but you’re thinking firmly in the present, and in some ways, the future.

In your curatorial practice and writing, what are your anchors? What are the themes in your work?

Sampada Aranke: It’s funny because this show feels like a little bit of an outlier and that’s exciting. We can talk more about that. But I work on Black American art history and I am actually a little bit of a fake art historian because my background is in politics and feminist studies. Then, I got my PhD in performance studies, but I found a home in this discipline—which is a little bit strange because art history can be quite a rigid discipline and can have very clear boundaries around what constitutes as art history versus, even, visual culture. But I was super lucky because I started teaching art history in art schools, so there was so much more elasticity and experimentation.

The art historians I teach with are rebels insofar as they never follow the protocols of what the field is constituted around. The work that I do—like the book that I’m writing right nowon images of Black death in the Black Power era—that project really started out of me being really struck by how much work was done by the Party to pay attention to their aesthetics and the politics of aesthetics, and the politics of art forms. At the time that this project started, it was 2008. In 2009, Oscar Grant was killed. I was getting my PhD at [the] University of California, Davis and was living in Oakland at the time. That was immediate and palpable. His murder wasn’t the first, of course, but it gave me this overwhelming feeling from being in the archive and looking at these images of Bobby Hutton’s death and George Jackson’s death, then having this happen in the same city where the Black Panther Party was founded. It was then that I started to think about how the Panthers were reconceptualizing death as a generative tool [and using it] to work towards revolution. They did that through speeches and getting people on the streets, but they also did that in the production and support of the production of objects and visual iconography.

That feeling of being in the streets [when Oscar Grant was killed] and people having posters that cited the Black Panther Party, in the 1960’s specifically, began to tell a story about how art has never been separate from political crisis for Black people in this country. It also [showed] how uncovering parts of that history might help us figure out a different set of strategies or tools, or even just feel grounded when we know that, yes, white supremacy is still alive and thriving—but there’s a history to that, and that might be calming or soothing. Or it can be motivation to keep the fight going.

TH: It makes me think about how we are so fascinated by and get so preoccupied by time—like in 2018 so many people were tapping into it being 50 years since 1968, which was one of many significant politically and culturally-charged years. People were making and mounting grand exhibitions and projects to highlight this moment. I’m curious for you, as someone who thinks deeply about that history and spends time in archives, do you see distinctions between then and now?

We have a lot of conversations about the similarities between what happened then with organizing that resulted in things like the Black Arts Movement and Black Power Movement and what artists and activists do now. We as cultural workers often make that connection—I mean, I’m sure I’m out there somewhere in the world quoted as saying, “This isn’t new!” But, for you, standing in a position where you’re looking back and looking at what’s happening now, is there a newness? Is there something distinct about now that feels different from history as you know it, keeping in mind that, of course, you didn’t live through the 60s?

SA: That’s a great question. I think there are distinctions in both ways. One distinction about my project and the objects [that focus on the] murders of Bobby Hutton, George Jackson, and Fred Hampton is the timeframe, which is a micro history from 1969 to 1971. [Also] the objects that I’m studying—print media, political posters—they were meant to die. They were never meant to live on. They were meant to be markers of a particular moment of revolutionary aim, and once the revolution happened they weren’t created to be memorialized or preserved or re-cast in the museum. And so much of that is because these were artists—but artists for the people. They were organizing. They had a different sense around what it means to be a cultural worker. Most things were done collaboratively and collectively, too. So the notion of preservation or the singular object, or even the copy as something that’s supposed to live on was never really figured. The objects I have to work with are sometimes just photos of these things because they were made on cheap paper, or things like that. That’s just one distinction that I’ve been thinking a lot about recently.

TH: It’s a kind of ephemeral production. I always think of it as not being created with the intention for it not to last, but it was created for the moment and under certain circumstances. The nature of the way and reason it was produced didn’t call for considerations like…using archival paper, for instance. Or using certain inks. Folks weren’t walking around at protests with signs professionally framed under museum glass to protect it from light.

But on the flip side, when you think about 2019, do you see that there’s a different approach to production of objects that are made around movement work. Evidence that, perhaps, folks are thinking more about preservation?

SA: Yea, I think the digital era has shifted a lot of things. I think it’s ephemeral in a different sense because now there’s an overwhelming flood of images. The scroll makes it a different kind of ephemerality. The specific ways circulation happens or the time of the object or the object’s life seems more stretched out or super condensed. I haven’t thought so much about the contemporary things that get made, but it does strike me that there’s a really active citation of these previous aesthetics or adages. There’s something about that memory that’s pretty incredible. These citations are embedded in Black aesthetic culture and in the way that the objects are made.

Where I come into the performance space in the 60s and 70s is through reconceptualizing the body—what it looks like, what it can do, what its aims are, its senses. That, for me, is the cutting edge when it comes to figures like Fred Hampton and his murder. [After his death] people had a different sense of what it’s like to die, which is really intense. And it does hit home for us now because we now have a different sense of what it means to die because we’re now exposed to people’s death in such a public way. It should be no surprise that people are making the connection to someone like Fred Hampton. That was a public execution.

TH: A big part of my practice has been studying this era and how artists have moved through these political movements. One of the things I think often about as a distinction between then and now, is how now the practice of artists who are aligned with certain political movements is much more institutionalized than it was in the 1960s and 1970s. I wonder how that changes things like circulation and effectiveness when they are moved behind the walls of these institutions. In the 1960s and 1970s these things were happening on the streets and were immediately accessible to and created for communities. They were made in community art centers and people’s homes—places that were established by the people, for the people—and so many cultural institutions weren’t checking for these artists and their work. Whereas now, it’s not surprising to see the visual culture and objects created for and in response to political movements sucked up by institutions, almost immediately. Even commissioned by those same places that undervalued this work for decades. Now, there are classes created around these topics, exhibitions in some of the most iconic museums in the world.

The gap between what is happening institutionally and what is happening on the street is getting smaller and this political work, in a way, is being canonized whether it’s a corrective revisionist curatorial approach or it’s a proactive way of doing it in the present. Today, it wouldn’t be surprising to find yourself attending an event at the MCA that is very politically focused or has actual organizing and activist groups involved as part of it.

For me, that can be really problematic for so many reasons. This is more of a comment than a question, but I wonder, how is the impact and effectiveness and the disruption changed when that closer mingling is happening—when you’re able to take a class at SAIC on social practice, or political practices? Or see a show that was organized by BLMChi at Gallery 400? It feels very different than when many leaders of these movements were building departments and teaching in some of the more politically charged schools in the country.

SA: I struggle with this too, because I’m on [that institutional] side now. I came from a very politically active and radical campus at [University of California], Santa Cruz. It was [a place that has connections to] Angela Davis, Bettina Aptheker and Paul Ortiz—all figures who fully believe in the opening of the university. As their students, so many of us were doing a lot of activism.

I’m at a college campus now, at SAIC, and it’s an art school. There’s a different kind of vibe and there isn’t that same sort of thing [as there was at UC Santa Cruz]. So I’m constantly telling my students, “The university won’t save you.” I know I’m part of the university, but I’m here to hack it and give them three hours a week to talk about radical histories that might help them figure out ways to dismantle it. I don’t over-identify with the university as a structure, and that’s my politics.

But your comment really strikes me because Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have The Undercommons, which has come into a popular consciousness in the academy. With the closeness between institutional spaces and political activism, there’s a cynical element and a neoliberal element to it that seeks to capitalize it and justify our fellows and the grants that we get. It tells me that there’s a fucking vacuum when it comes to places for people to go. It’s so hard to pay your rent, let alone enough resources to open your doors to create a community space. I think in the 1960s and 1970s, of course, people were under economic strain, but it was a different composition of finance and politics. Part of me is [for the people who are] going in and infiltrating these spaces and saying, “No, you’re going to give us three hours a week or we’re going to raise hell every single day”—at it’s best, that’s a kind of reclamation. But I think, really, what it is is people saying, “Look, you displaced us and are capitalizing off of X, Y, and Z—you can at least give us this thing.” It becomes an extraction of these institutions’ resources—whether that’s space or time. It’s doing things undercover. I think that’s become a real place of survival for folks. But then I still wonder is it creating collective capacity? Is it opening up new horizons? I don’t necessarily think it’s about building revolution, but maybe it’s about building a bunch of tiny ones. But it’s an interesting problem that we’re in because [these institutions] are so full of resources.

TH: Speaking for myself, on an individual level it can completely shut me down when I start to peel back the layers and ask questions like, “Okay, this is a giant institution, they have a lot of money, where did that money come from?” I remember losing sleep when working at the University of Chicago just thinking about all of the problematic things they’ve done in Chicago and globally, and still do. I remember telling myself that I was going to do what I can for as long as I can—get as much money as I can to artists and community organizations as a kind of reparation—but damn! What’s the sacrifice in the process?

Then I think about the individuals within some of these institutions who are pretty prolific and we’re lucky to have them. And the folks who think—not to speak for them in any way—but they think in a similar way that you do in operating clearly. They are in the institution and not of it. But even so, many of these institutions have found a way for these people, their voices, their brilliance, their interrogations, and reputations to work for [the institution’s] benefit and bottom line. Even, to a certain extent, to align themselves with those radical views.

So, how has your work in performance studies evolved over the years?

SA: It started because I was reading a lot of Frantz Fanon in undergrad and was struck by how he talks about the colonized body, specifically. It was a rupture for me because up to that point my training wasn’t critiquing Western Enlightenment, especially from a feminist perspective. Feminist theory gave me a chance to pay attention to the sensual and a political critique of masculinist and capitalist forms that train the body or violate the body. I’d been reading a lot of Black studies and kept coming across Fanon at a really young age—and he was talking about things like muscular tension in the colonized subject and all of these particular kinds of examples of it not just being about the taking over of the mind but a recomposition of the bodily form. Those two trainings together [helped me understand] how the Black Panthers visualized bodies in their work. I came into my studies wanting to form a reconceptualization of the radicalized body and, specifically, through the lens of the Black radical tradition. So when I think about my work, I’m constantly returning to the question of relation—not like equivalence—but looking at things like the blood-stained mattress and the horrifying scene in Fred Hampton’s room. And how the Black Panthers opened the doors for people to come in and see what happened. And that’s an attention to how [a handful] of people in a space are composed, and it helps people make sense of their own lives in relation to that violence. I was noticing more and more that Black artists, specifically, are constantly aware of that dynamic.

Even in a more traditional gallery setting, work like Melvin Edwards’, is asking us to think about where we stand in relation to that thing [or an object]. And that has bigger repercussions, like where do we stand in relation to that social violence, political violence, or aesthetic violence? That’s the way that I think of performance studies, which is through theories of embodiment and how that folds in.

With the curatorial work that I’ve been lucky to do, it impacts how I think about the composition of a show. With “Feel Me?”, this is the first show I’ve done that wasn’t all Black artists. I have this 1960s and 1970s part of my life, then I have this 1990s and 2000s part of my life. I’ve been really lucky with people like Sadie Barnette who has been really trusting of me and letting me write about her work. Same with Kambui Olujimi and Zachary Fabri and artists who are working now and developing a vocabulary that responds to the 60s and 70s but does it in a way that’s expansive. And those artists are so cognizant of the way that flesh works—and things like sweat and spit. And they’re coming out of a tradition that’s a Black art historical formation but also a non-Black art historical formation. Those artists have really helped me figure out what it is about that activation that strikes me.

“Feel Me?” came out of a similar set of questions but from a feminist mode of critique, which, for me, is a return in a lot of ways. Some of the works are quiet, some are more directive, but they all are grasping at what it means to compose a body out of objects and that is a central theme in all of my work. Whether it’s my academic writing, art writing, or curatorial projects, how do we think of the composition of bodies in and through objects?

I cannot, by any means, take credit for that. It was actually Huey Copeland’s work that completely blew my mind in Bound to Appear. You know when you read something and end up thinking that this person has just articulated what many of us are grasping toward? It was like that.

TH: He’s a gem.

SA: He can do no wrong!

TH: The show is so concise and makes its point using such a small number of works. What was the editing process like for you and how did you choose the final eight works?

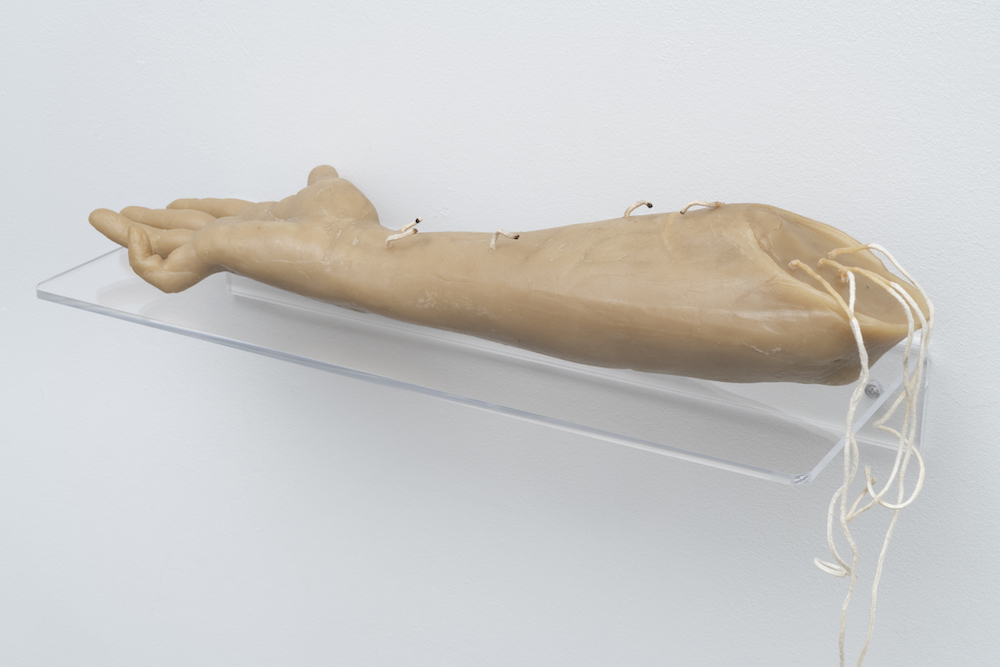

SA: So much of this project is studio work or studio practice. Because it’s the germination of an idea that’s still in-process, it started off at first as I was thinking about Sadie’s cans and Tina’s arms. For me, those two works were thinking about touch and contact in very striking ways. When I see Sadie’s cans—these glitter-bombed, awesome, semi-crushed objects—I think about the lips that were on them. Or the act of pleasure and enjoyment. With Tina’s work I was struck by how they are specifically organized around thinking about pain in relation to her body, and a marking of the self by casting her own arm in materials that intensely cite a kind of violence. Yet, these two pieces together—I had a vision of how they would be installed. But then when I came into the space and got the works, I realized I wanted them to be together and sit together as these two different approaches to care or intimacy.

Those two pieces were what got me going. Then, I immediately thought about Xandra [Ibarra], Kristan [Kennedy], and Dylan [Mira]—I needed to get them into the show. It’s very rare to see Xandra’s work in conversation with Tina [Takemoto]’s work, for example. I wanted these expanded practices that are happening simultaneously that are citing each other in different ways [together in the show]. I also knew I wanted this large Kristan Kennedy painting.I was interested in scale and capturing things large and small in order to think about the bigger gestures that Xandra’s video piece and Kristan’s painting [make] and also these smaller gestures like the crushed sculpture [by Kristan Kennedy] put a wrench in this idea of spectacularity.

Dylan’s piece [7 Skin Night Repair Essence] really hovers between a lot of those things because it’s a sculpture that’s multifaceted—it’s water, staining, a fashion object and industrial object. It’s been interesting to see how people have been gathering around this piece. Its placement has a bodily relation for people. I originally wanted a different piece from Dylan, but she [offered] this piece, saying “I think this is the one you actually want.” And the minute that I saw it [I knew she was right]. It’s human height, it mirrors the body so people have really been gathering around it to see how the mechanics work.

TH: It takes a lot of clarity to distill a show down to such a small list of objects. And what you said about care is so spot on.

SA: That’s really interesting, too, because even Dylan’s piece requires a kind of care. All artists do this to a certain extent, but you know when you install a work and the artist gives instructions and preferences? Dylan’s piece requires that we refresh the water and Mugwort tea every week. So there’s an element of implicating the space and the gallery. The curator or gallery attendants are caretakers of the work and that feels like it enlivens the piece. Kristan is also a writer and her work is incredibly poetic so her instructions for installing the work were equally poetic! They were very intuitive instructions—grip it here, tug it a little bit, then move it here, and then drop it…and the instructions worked! Or Tina with the arm pieces. She explained that there was a little bit of bloom with the arms, or to arrange the pins in the arms in whatever way seems the most conceptually appropriate. There’s a real intention and attention to it. Each of Sadie’s cans were individually wrapped. There’s something there about a bodily attention or an attention to flesh and form, and an acknowledgement that we don’t live in a realm where we just hang some pictures on a wall, right?

TH: As a viewer, you don’t often get the understanding that the curator or the folks conceiving of the shows have an additional responsibility of continual care taking or are actually, in a way, collaborators in these shows unless the curator makes it a point to forefront. Either the curator says, “Yes, I’m a collaborator in this show,” or they take the approach of, “I’m taking a step back and letting the work do it’s thing and speak for itself…”

In the description [of the show] you wrote, “There’s a tiny space between feeling and knowing. Worlds of engagement are possible within that space.” Can you talk more about that? What is that space?. Both of those statements have a kind of push and pull—it might be a tiny space, but within it there’s a world of possibility. But I’m curious to know how you’re thinking about it. The entire statement drew me in.

SA: I was thinking about another false dichotomy between knowledge in a Western Enlightenment sense that is thought of as something that men do. Or the formation of early binary structures that we’re encumbered with today. I was thinking about that in relation to how so many feminist movements are thought to be about feelings. And, again, these are fake things and almost like stereotypes and cliches. But I was also thinking about that in relation to the gut feeling and intuition, and having a sense about something to then have it verified. Then, when it’s not verified it almost destabilizes your sense of self. So that gap between feeling and knowing, whether it verifies who you are or destabilizes you—the most striking and impactful moments are the tiniest moments within that. They’re not these grand, obvious moments. It’s more like, “I had a feeling that someone was betraying my trust, and then I found the receipt…” That really small thing is shattering.

I was listening to W. Kamau Bell who had a joke in one of his sets about when he first realized he was Black—he was six years old and playing the kissing game. He wanted to kiss a white girl and she didn’t want to kiss him. It wasn’t as if she said she didn’t want to kiss him because he was Black, but for him [it was understood in that way] and that was shattering.

This show was a way to think about the possibilities within tiny, tiny moments—not the overwhelming, spectacular moments, or even the explicit moments. But the small ones—gestures that happen between people that either affirm or destabilize. And where are the points of connection? When I was thinking about this show in relationship to those questions, I was thinking about not just the things we say, but the feelings that are associated with them or the way our body might leave a trace of a feeling behind.

The cans, for me, raise so much of the feeling of being at a party and having a beer or a drink in your hand. The can can’t remember those things, but the can has your fingerprints and your saliva. It has a part of you on it. And when you throw that away, and it’s trash or recycled, a part of you goes with it. That sounds so hokey pokey, but it’s so true. To glitter-bomb those is about what that really small moment is about—what the holding of that can is and what potential that can spark in us.

TH: And finally, is there anything else you’re working on or have coming up that you want to shout out? You’re working on a book, which is huge—and congrats on even saying out loud that you’re working on a book!

SA: Thank you! It took me a lot to get there! I hope to take on more projects like this. This show doesn’t have any plans on touring right now but I’m hoping to figure out a way to make it last beyond [its run] by maybe soliciting some writing from the artists or doing a chapbook. So I’m thinking about other iterations. We’ll see.

Featured Image: A portrait of Sampada Aranke wearing all black and standing in front of a large, dark door and steps. Photo by Kristie Kahns.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Brian Guido.