“All portraits are fragments,” says Riva Lehrer, “it’s representing someone through a single moment in their life; so any portrait is an act of reassembly, you get these clues and you try to reassemble them into some view of the person.” In a way, this is what I was doing as I read Lehrer’s new book GOLEM GIRL: a memoir: scouring her words for insight into what makes her the person she is today.

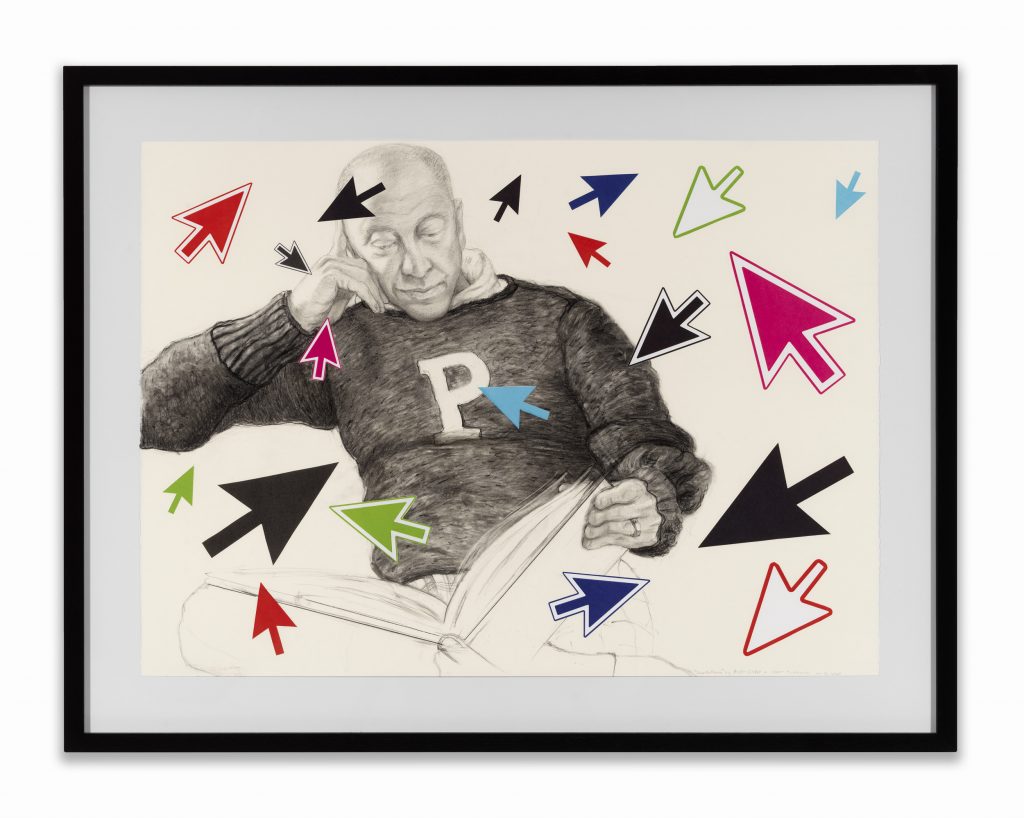

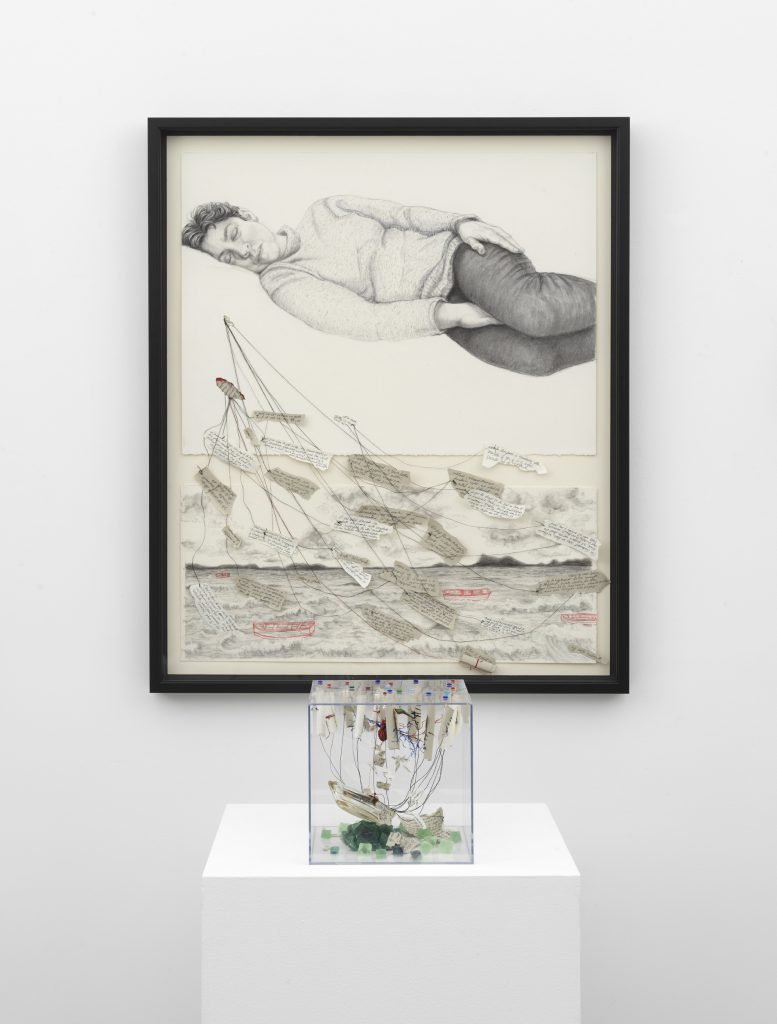

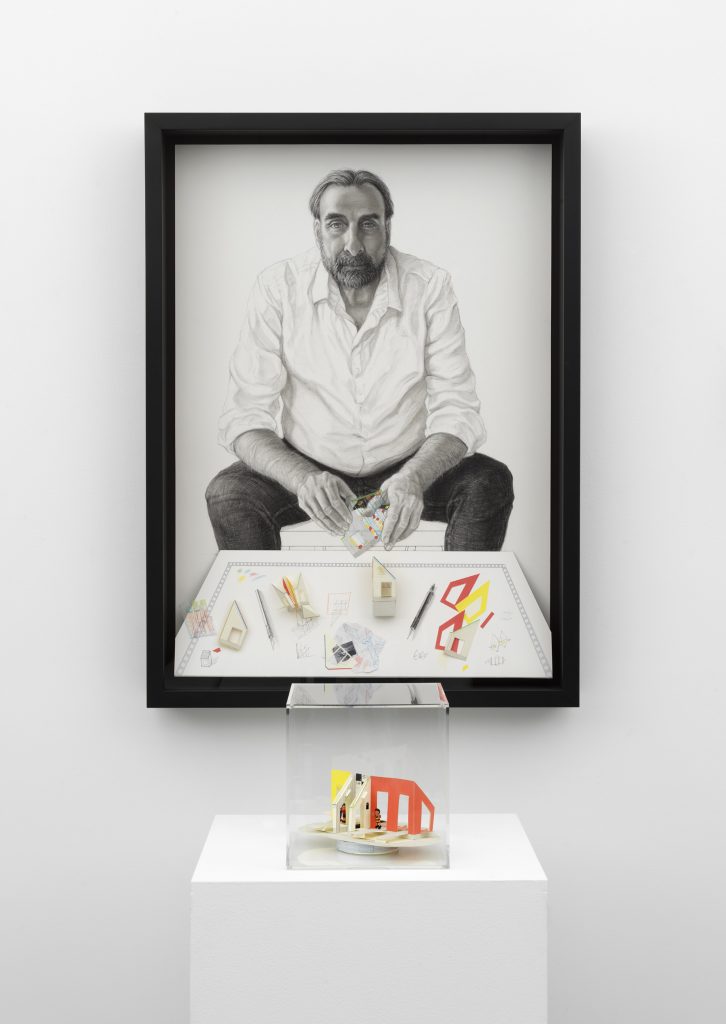

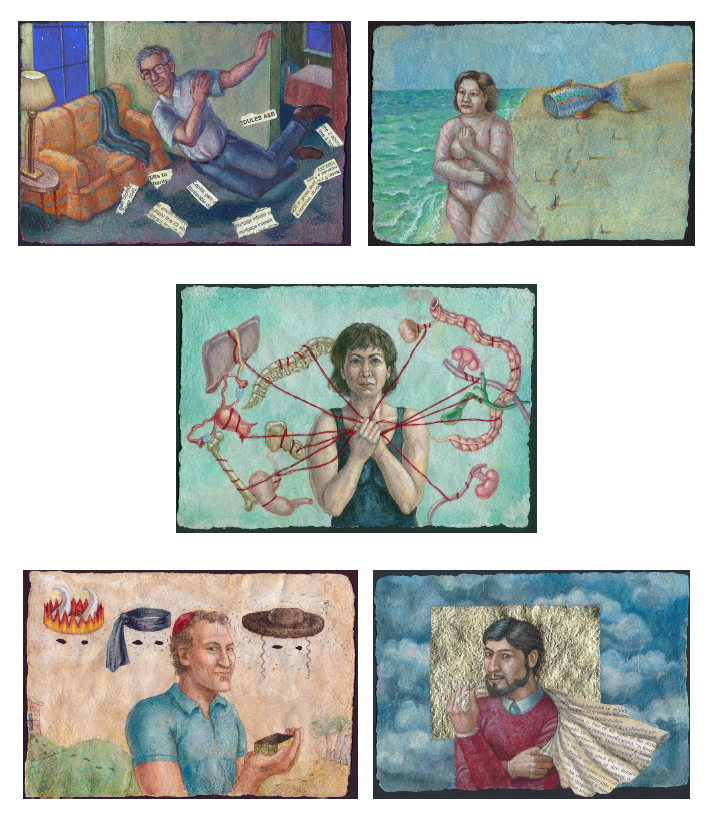

‘Author’ is just one of many hyphens in Lehrer’s well-established artistic career. She teaches at Northwestern University and she curates, but she is perhaps best known for her portraits of people “whose physical embodiment, sexuality, or gender identity have long been stigmatized.” As a Disabled artist herself, Lehrer has a unique ability to capture a person’s form in an honest and expressive way through her evocative works. I had the pleasure of speaking with her to discuss her background as well as current projects.

Lehrer’s artistic talents are familial.

Courtney Graham: [In your memoir,] you talk about your mother, Carole, being an artist — a very creative person who “found outlet in small things, in the permissible, restricted expressions of women with children.” This reminds me so much of my own mother, and even myself in some ways. What was it like to witness your mother’s creativity and how did that translate to your own interest in artistic expression?

Riva Lehrer: Art became the family identity in a way — this is what we do! Both of my brothers can draw, but I’m the only one who really pursued it professionally. Our family takes pleasure in visual things and material beauty.

CG: The school art room is such a solace for so many people, and you describe it as “the only place where [you] could be the leader, not the follower.” What was it about art that has been so transformative for you?

RL: From my earliest memory, I would get praise [for my art]. Nobody expected anything from me, so anything I did well was remarked on. For Disabled kids, your big party trick was surviving. [At the time] many kids like me were institutionalized or didn’t really have a public life. It reflected back on [one’s] parents as well. They invested a lot and if their kid was then praised for talent, it was reassurance.

CG: You and your mother both spent a lot of time in the hospital, that’s a really difficult shared history. Can you talk a bit about how those experiences shaped your relationship?

RL: I don’t think either of us were afraid of the hospital, but afraid of what might happen there. We knew the language and could navigate the power structures. Children’s hospitals and adult hospitals were very different — my brothers were not usually allowed to visit, so it was mostly my parents and grandparents around me. At the children’s hospital, my mother was my conduit to the world, completely. When she was at the adult hospital, I wasn’t in the position to do that for her. It was both a shared and very different experience.

Lehrer grew up with the support and understanding of a parent well-versed in medicine. Her mother Carole had experience as a medical researcher, simultaneously giving her “education [that] bestows self-respect and efficacy that buoys [parents] through the grief,” while also leaving her no “comforting ignorance to hide behind.” But it wasn’t until arriving in Chicago that Lehrer became deeply connected to the Disability community.

CG: In 1996, Susan Nussbaum convinced you to attend a meeting of the Chicago Disabled Artists Collective at Victory Gardens Theater. It sounded like a really influential moment. How much of your connection to the Chicago Disability community can be attributed to that?

RL: All of it. I mean, that was one of the absolutely pivotal moments of my life. I didn’t want to go, I thought it would be tedious at best and pathetic at worst — and it was neither. I had never seen Disabled people with style and that alone shifted my perspective.

In her book, Lehrer recalls how members of the collective “spoke a shared language developed through activism, through protest marches and Disability Rights organizations, a universe of advocacy I knew nothing about.”

CG: You also write about some of your first encounters with language like ‘crip,’ person-first language, and Disabled with a capital D. How has such language impacted your identity and how do you see it continuing to evolve?

RL: It’s definitely still evolving. Back then, there were no good terms. All of the words for disability and the kinds of disability were pejorative, the clinical language of brokenness. There are countless ways to be disabled and every community has to go through their own wrangling with what they’ve been named. The fights over language going on all over the country, with any kind of self-identifying community, are coming out of words that have done damage.

The Disability community brought new language, but also new people into Lehrer’s life, many of which have become her collaborators.

CG: I was delighted to see a number of familiar faces in the images of your work that punctuate the book. You often refer to the people you depict in your artwork as ‘collaborators.’ How do you choose them?

RL: Most of the time it’s because I know something about their work — I’ve gone to one of their performances, read or witnessed their work. They are writers, academics, performers — quite a range. My big interest, really, are people who undergo stigma; something about their physical presentation gets them stigmatized and they make work related to that. I’m interested in their take on the body.

CG: You write about discovering the work of Frida Kahlo not long after moving to Chicago and studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I certainly see some connections between the two — portraiture and the body — but perhaps what reminds me of Kahlo’s work more than anything are your almost surrealist environments. How do you decide on the settings for your portraits? For example, your Family Album?

RL: In the family portraits, I was trying to figure out what role we each occupy for each other. We were all sort of so different, but there’s a ‘Lehrer-ness.’ There were moments when we were all pulling in different directions and I wanted to think of us as a fairy tale — what’s each character off doing? I’m in the center because I felt like I was a grenade sort of blowing up everyone’s experience.

Each of Lehrer’s portraits is so narrative, it seems storytelling comes naturally to her.

CG: You spend a lot of time getting to know people before you make a portrait of them. How was the experience of reflecting on your own life in preparation for writing your memoir similar or different?

RL: I’ve done so much lecturing on my work, way before I started to write this book. Usually I have to say, “I’m Disabled and here’s my take on disability.” Then I talk about who sat for me and our stories [become] kind of intertwined. So I’ve had years of preparation in telling stories about other people. You can’t really understand my work until you know who I’m working with and why I’m working with them.

Lehrer wields the often under-estimated footnotes with such command and grace, they quickly became some of my favorite parts of the book.

CG: I found the footnotes in your book to be probably some of the most interesting footnotes I’ve ever read. Some clarify a point or direct the reader to a related article, others are really humorous additions. At what point in the process did these notes make their way into the book?

RL: I fought to get those in! I love footnotes — sometimes you have this really intimate conversation in the footnotes. My early drafts had many more than the finished book does; it would have been 40-50 more pages with all of the footnotes.

The epilogue of Lehrer’s book acknowledges the current global crisis we all find ourselves in. It cannot be understated that the Disabled community has been disproportionately affected by the pandemic due to pre-existing conditions and the severe breakdown of close personal contact, which many Disabled people require for their health and safety.

CG: Because your portrait process is so intimate, how has your practice been affected by the closures related to the pandemic?

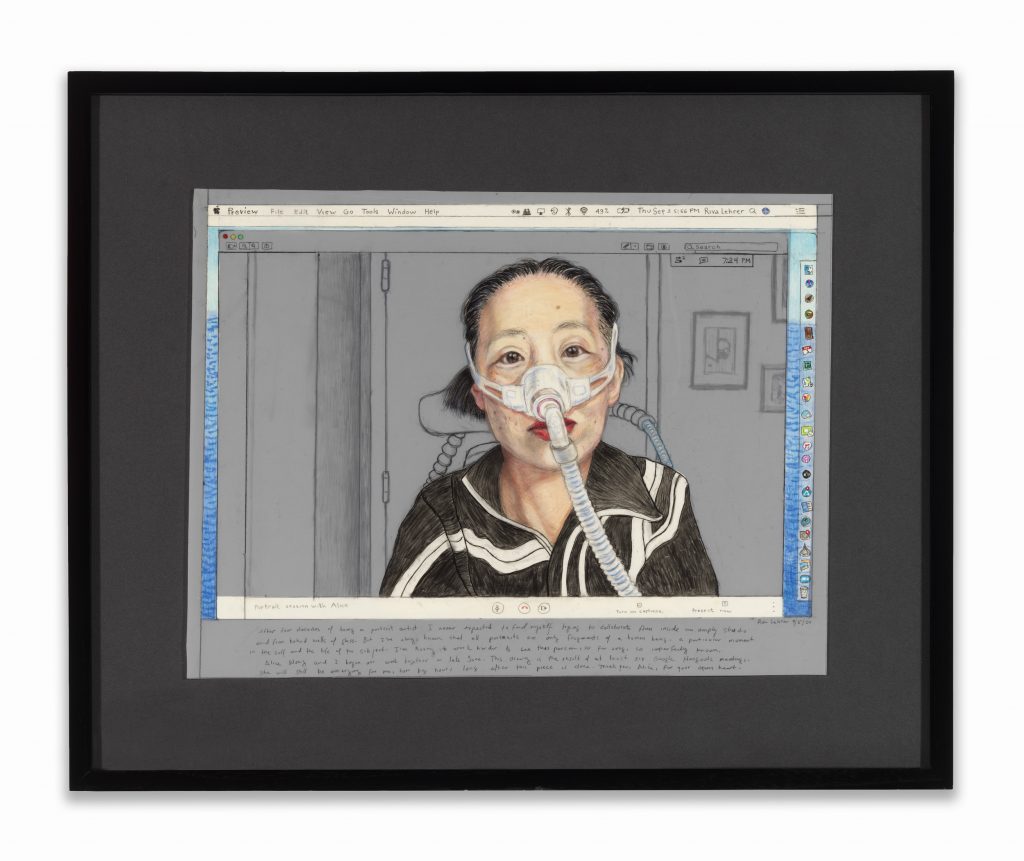

RL: I finished two large portraits, including one of Alice Wong, over Zoom and partially by mail. Neither method makes me happy, I hate them both, but being Disabled is always about facing the fact that the way you used to do things is not always available to you. [Portraiture involves] mechanisms of choosing; what you choose and what you don’t really change when all you have are long distance methods.

CG: You have an exhibition at Zolla/Lieberman Gallery called Pandemic Portraiture. What do you hope people take away after seeing this work?

RL: I’m trying to respond to our time in the best way I know how. It’s incumbent upon me to do something related to my practice until hopefully the world changes.

Riva Lehrer’s Pandemic Portraiture is on view from October 10 through November 28th at Zolla/Lieberman Gallery; you can see more of her work and find her book GOLEM GIRL: a memoir on her website.

Featured Image: Zora: How I Understand, 2009 by Riva Lehrer. A color drawing of a woman crouched behind a black dog. Her bare legs and hands peek out from beneath the animal, her shoulders and head of red hair rest atop its back, obscuring her face. The dog holds one paw off the ground and looks directly ahead, one eye clouded or missing. Fall leaves cover the ground with several eyes poking through. Courtesy of Zolla/Lieberman Gallery.

Courtney Graham is a Chicago-based arts administrator, writer, and event planner. Her writing and research focus on accessibility for people with disabilities in cultural spaces, exploring access, and spotlighting artists with disabilities. Courtney serves as the Associate Director of Engagement Programs at the Art Institute of Chicago. She completed her BFA at the University of Michigan and her MA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.