Upon entering the long, dim exhibition hall at the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, the first encounter in Reinterpreting Religion is Yvette Mayorga’s bubblegum pink, white, and gold installation Guns and Virgins (2018). With its offering of confectionary AR-15s, cartoonish police officers, American flags, Brown prostrate bodies, and a pair of frosting-drenched basketball shoes, Mayorga’s physically flattened yet confrontational work spurs the viewer to lay down their divine expectations at the altar of America’s violent tendencies and obsessive consumerism. Though Christianity, the predominant religion in the United States by far, promotes teachings centered on loving your neighbor, accepting the weary traveler, and turning the other cheek to violence, 81% of “white, born again/evangelical Christians” voted for Donald Trump despite his penchant for encouraging violence on the campaign trail and admittance of sexually assaulting women. Throughout Lauren Leving’s curatorial process, she recognized that religion seemed to have been commandeered as a tool to divide rather than unite communities across America.

Though the exhibition kicks off with candy-coated automatic weapons, the intention of Reinterpreting Religion is to “put different artists working with their own religious or spiritual beliefs in conversation with each other to strengthen community and slightly minimize that divide that we’re experiencing,” said Leving in an interview. Mayorga’s appropriation of the architecture of religious spaces calls attention to the hypocrisy of white Christians who continue to support Trump’s violent, white supremacist regime, while also serving as a reminder that the icons of America she presents on her altar are man-made, and as temporary and malleable as the frosting she used to create them.

Adjacent to Mayorga’s installation is the work of Sarah Maple, who questions the transformative power of liturgical garments and the effectiveness of modesty as protection against sexual violence, with her photo series of self-portraits where she is presented wearing an “Anti-Rape Cloak.” The need to don the body-consuming cloak highlights the artist’s lack of physical autonomy as she moves through the world, and the series of disparate settings in her images reveals the incredibly troubling reality that sexual danger can be just as looming on an empty desert road (Mojave Cloak, 2015) as within the perceived security of a childhood bedroom (Bedroom Cloak, 2015).

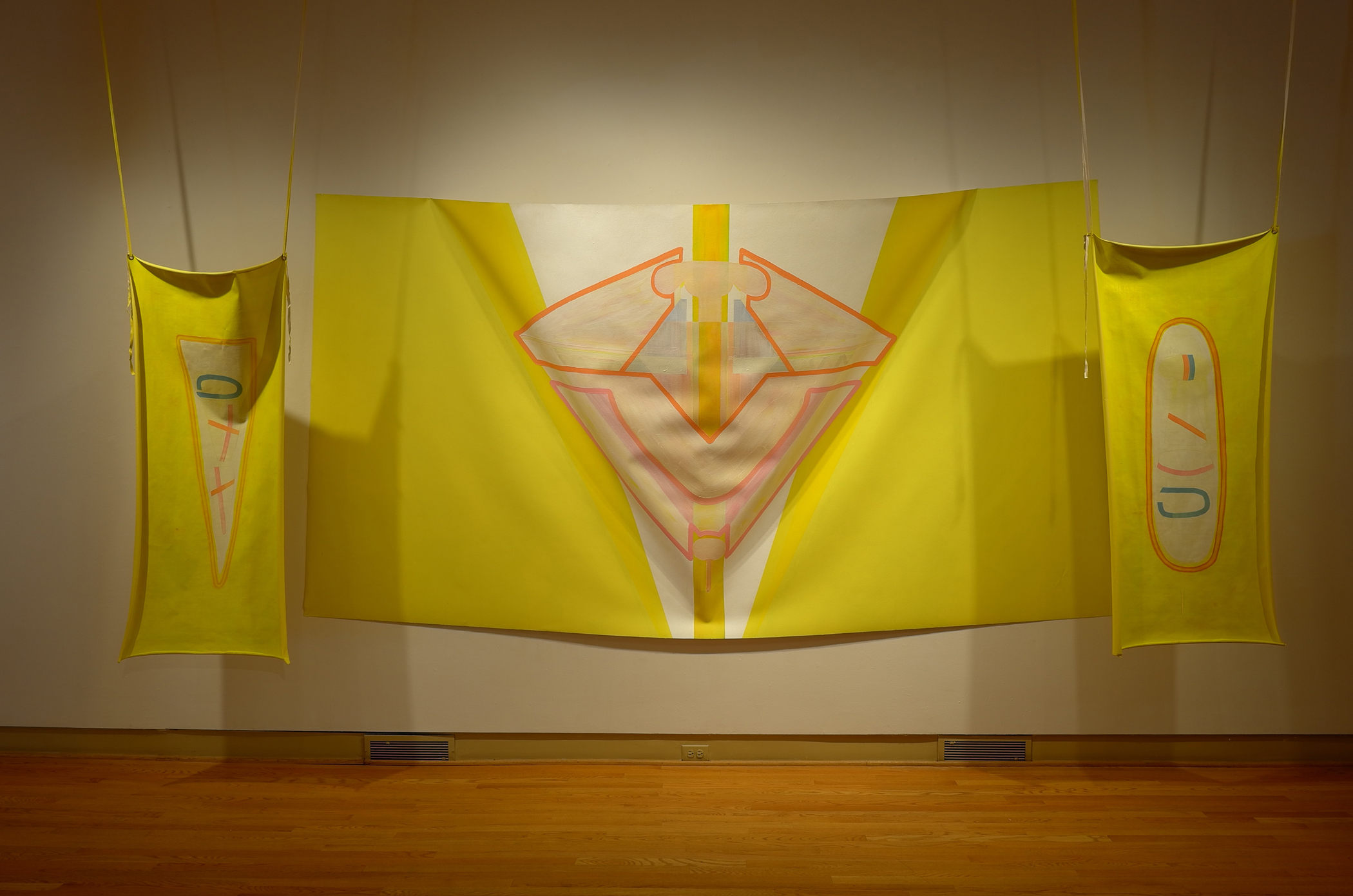

The vibrant work of Roni Packer suffuses the room with light and offers a moment of emotional respite with her luminous canvas piece Trying to Paint G-d (2018). Gently draped from the center of the main gallery wall and flanked by two rectangular canvas banners hanging from the ceiling, the entire piece appears as washes of yellow floating delicately away from the wall and into the space of the viewer. The softly geometric pink and coral diamond in the center of the piece holds a light blue structure that seems to recede back in space – like the viewer is given a glimpse through a doorway into a metaphysical realm beyond. The abstract nature of the work combined with the delicate and joyful palette constructs an interpretation of “G-d” that is far removed from the traditionally Christian, patriarchal presentation of the higher power as an old, white, bearded man casting down judgement from above.

While Packer’s work is open and room-filling, Lakshmi Ramgopal’s intimate installation Maalai (2017) invites the viewer into a densely arranged and deeply personal devotional space. Nestled into the back corner of the gallery is a low wooden table, on top of which sits a diary, framed photographs, brass bowls and bells, small statues, dried flowers, and speakers softly playing music. The viewer is invited to engage with the objects on the table, and the inclusion of the diary makes it clear that you are a voyeur to this spiritual practice, but also a welcome guest. The semi-enclosed corner location of this piece — along with the holistic sensory experience presented through the vibrant colors, the soft music, the floral aroma, and the invitation to handle these personal objects — positions the body of the viewer as a central component to this work.

Rhonda Wheatley’s work, presented on a small platform built around a central column, requires more active viewer participation. The 14 assorted jars and bottles from her series Elixir Stills and Cure Bottles (2017) contain natural ingredients like herbs, sea horses, cicadas, snake bones, moss, dried flowers, sand, succulents, and crystals – most set within congealed resin. The jars are titled according to the powers the artist infused within them during their creation – for example, “Elixir for relinquishing the need to control situations and other people,” “Self-honesty truth serum,” and “Elixir for healing the roots of or unlearning one’s own prejudicial hatred of groups of people.” In the exhibition checklist, Wheatley instructs the viewer to gaze directly into each jar depending on their desired outcomes – but only if the gazing is “100% voluntary.” While religion is the connective tissue of spirituality, uniting individual believers with like-minded communities, Wheatley’s work proposes thorough self-inspection as the transformative practice necessary to initiate broader societal change.

The exhibition also includes two women documentarians working on projects about female religious leaders who have been denied official roles within the Roman Catholic Church (seen in artwork by Giulia Bianchi) and Mormon Church (artwork by Kristine Solakis) due to their gender. The combined work of the seven artists in Reinterpreting Religion provides an expansive reaffirmation of the feminist slogan “The personal is political” through the lens of intimate spiritual experience, and looks to female leaders to create future religious institutions built upon the ideals of peace, equity, and inclusivity.

Reinterpreting Religion is on view at the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art until July 29, 2018.

Featured Image: Yvette Mayorga, Guns and Virgins, 2018. Mixed media installation. Mayorga’s bright pink altar is painted directly onto the gallery wall and highlights assorted frosting-covered icons related to police and gun violence and American consumerism. Photo courtesy of the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Annalise Flynn-Taylor is a curator, writer, and art historian based in Chicago. She is the Director of Exhibitions for ART WORKS Projects, a nonprofit organization that uses art to advocate for human rights issues around the world. Her work focuses on practices that expand the definition of art making and intersect with social justice.

Annalise Flynn-Taylor is a curator, writer, and art historian based in Chicago. She is the Director of Exhibitions for ART WORKS Projects, a nonprofit organization that uses art to advocate for human rights issues around the world. Her work focuses on practices that expand the definition of art making and intersect with social justice.