Featured image: Exhibition view of Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine at the Smart Museum. Image courtesy of The University of Chicago.

Each canvas, large, small, and in between, draws the viewer into an enveloping world of kaleidoscopic colors. The painter Bob Thompson has been called the “first natural American psychedelic colorist” and the exhibition This House Is Mine, now on view at the Smart Museum, reveals how his stylistic approach to art ebbed and flowed over his brief career. This massive show with over 70 works of art highlights the impactful contributions of Thompson’s oeuvre that still reverberates in art today. Just as he looked to the Western art canon to draw inspiration, contemporary artists today continue to do the same.

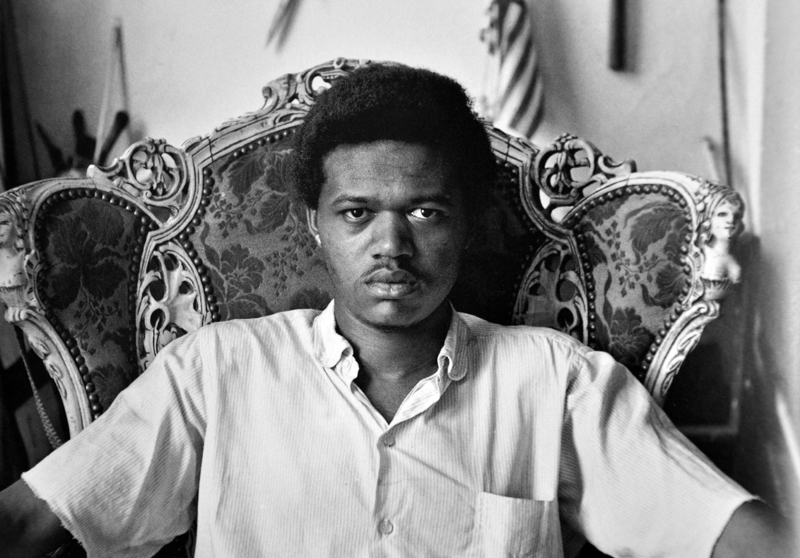

This House Is Mine marks the first major survey of Thompson’s work in over twenty years. Born 1937 in Louisville, KY, Thompson lived a brief but monumental life up until his tragic death in 1966. At only 28, the world lost a visionary painter, one who was remembered by painters, jazz musicians, and beat poets just as his works were inspired by them. His searing canvases set the Smart’s galleries ablaze, the same way they lit up galleries almost sixty years ago.

This expansive show traces the evolution of Thompson’s work and continuously draws us back to his original inspirations: German expressionist Jan Müller, free jazz, French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin, and life as Black man in 1950s America. Whether his identity was an impetus for his art-making, or his work was a way of grappling with life in a racist nation is up for debate. But his exploration of identity is seen in his reimagining of mythical stories and grand paintings of Europe’s famous artists. Going against the grain, Thompson refused to conform to the Abstract Expressionist movement dominating the art world and market at that time. Instead, he found inspiration in the neatly depicted human figures of the past.

Visitors to the gallery are immediately confronted with Thompson’s painting Blue Madonna (1961) situated on a tall freestanding wall painted a vibrant blue-purple shade. The large work prominently features a Mary and Child motif that captivates the viewer and foreshadows how the rest of the show unfolds. As your eyes adjust to the colors in front of you it is hard to look past this painting to the exhibition introduction or label. The basic perspectives of a figurative painting – those neatly delineated foregrounds, backgrounds, and subjects – are missing. The artist blurs everything together into one flat surface of people, horses, and flora with barely a shadow to give depth. Straddling this line between representation and abstraction, through a co-mingling of bodies and forest, is only heightened by the unnatural colors of Thompson’s palette. Blue Madonna recalls the canvases of French artists in the late 1800s and early 1900s who were defiantly pushing against classical modes of painting, just as Thompson pushed right back against abstraction. He found a home in these avant-garde paintings and a kinship with their creators’ motives.

The show continues into the first gallery with mesmerizing radiant colors marked by visible swirls and dashes of paint. Thompson’s palette recalls Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat but better represents divine intervention than any great Renaissance painting. The pulsing shades of cobalt blue, lime green, and saccharine oranges are superior at capturing the unknown form of a god or an angel. He follows this theme of vibrancy and religious material throughout the rest of the galleries of the exhibition.

From there the exhibition takes a thematic turn with Homage to Nina Simone (1965), an ode to the musician-activist who also used her medium to challenge dominating, white narratives. The exhibition then, oddly, goes back in time to the dark, moody colors of Thompson’s early career. This shift in tone seems abrupt and takes the viewer out of the psychedelic scenes of nature and religious stories. The rather realistic painting Self Portrait in the Studio (1960) seems to demonstrate what was most important to him at that time – his paintings, studio, drums, and a short instance of solitude. This moment of respite for the viewer and Thompson is quickly thrown aside as the show explores Thompson’s darker-themed work.

From 1962 to 1963, Thompson reworked Francisco Goya’s monster-filled prints, Los Caprichos (The Caprices), for his contemporary America. Goya, a famous Spanish artist from the late 18th and early 19th century, is best known for his work that reflected the turbulent life on the Iberian peninsula in the late 1700s. Arguably, as the exhibition text alludes to, Goya’s prints of nightmarish scenes are closer to the lived Black American experience than any other inspiration Thompson found. Both Tree (1962) and Caledonia Fight (1963) display absurd punishments unfolding that are cruel and unjust, and yet it is impossible to tell who the aggressor is and who is the victim. Each swirl of humans, monsters, and winged creatures is given faces, unlike his other compositions. They convey a range of emotions that further muddle what the narrative is and who to root for.

Thompson rarely addresses white supremacy straightforwardly. Typically, his canvases avoid a clear-cut message of racial violence, opting for oblique messaging that viewers must sort through on their own. There is one painting in the show that does depict a heinous act of violence. Placed inside a smaller room in the gallery sits Thompson’s The Hanging (1959). A seemingly hastily painted scene, with the canvas and base layer peeking through the darker shades of the paint and a rough outline of a figure wearing a hat. Far away in the back, the crime occurs on a smaller scale placing the viewer amongst the scene’s voyeurs. We are reminded of the real fear looming over Thompson’s life as a Black American in the United States during the mid-1900s that still pervades to this day.

To counter the violence in the previous room, the exhibition turns to Thompson’s wondrous love letters to Black musicians like Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, and the aforementioned, Nina Simone. Their melodies and interludes are translated through Thompson’s brushstrokes in Ornette (1960-61) and Garden of Music (1960). Referencing religious motifs like the Garden of Eden or the frescoed ceilings of Renaissance cathedrals, he likens their music and works to a spiritual form. Ornette’s circular composition mimics the free-flowing nature of jazz musicians riffing. A performance style that leaves the audience unsure of where the tune may go next but eternally enraptured by the sound. Thompson channels this in his work, encouraging the viewers’ eyes to move around and around the canvas looking for the next thing that captures their attention.

In the final galleries of the exhibition, Thompson continues to explore religion, inspiration from his travels, and paintings by European masters. One of the last works of the show is the small painting Five Cows with Blue Nude from 1965, the year before he died. We catch a scene unfurling in front of and away from us. The colorful bovines and sparse human figures venture further into the distance, into an unknown future. This small work plays with the colors seen in his previous paintings while creating a clearly defined foreground and background. The great expanse of yellow and blue sky and clouds gives a moment to pause to think of what Thompson could have gone on to create if his life wasn’t cut short so early and what we will do in the absence of his fervorous colors.

Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine opened on February 15 at the Smart Museum of Art. The vivid fever dream of a show traveled from the Colby Museum of Art in Waterville, ME, and will make stops at the High Museum in Atlanta and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in the coming months.

Elizabeth Upenieks is a Chicago-based curator, writer, and art historian. She earned a BA in Art History from the University of Texas and an MA in the History of Art & Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her most recent projects include What We Do in the Shadows and PLATFORM 26: Myoung Ho Lee, Tree…#2 at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA.