Featured image: In the foreground of the image is Proton Pack Record Player by Allen Moore, a replica Proton Pack modified to play records; Trap Coffin by Allen Moore, sound installation, OSB coffin painted black with speakers, stick painted hot pink, red LED light strip. In the background from left to right: Solar Eulogy by by Allen Moore, casted graphite and glue on canvas, 36 x 48″; Red Shift 41 by Allen Moore, casted graphite and glue on canvas, 18 x 24″; Blue Shift 48 by Allen Moore, casted graphite and glue on canvas. An installation that includes a record player and coffin with speakers on a square pedestal low to the ground. Behind the installation is a gallery wall with three rectangular black paintings that includes one large rectangular black canvas with 54 cast shapes; one rectangular panel with 41 graphite and glue cast Pac-Man ghosts; one rectangular panel with 48 graphite and glue cast Pac-Man ghosts. Image courtesy of Amy Shelton.

Full disclosure: Lauren Iacoponi is the gallery manager at Cleaner Gallery + Projects, she is a close friend of the artist and assisted with the production of the exhibition. This article includes quotes from Moore based on an interview and conversation held between Iacoponi, Moore, and his partner Christina Warzecha on March 14, 2022. Please note that Iacoponi’s previous publications on Cleaner Gallery + Projects came at a time before she was affiliated with the gallery.

Allen Moore returns to Cleaner Gallery + Projects for his 4th exhibition with the artist-run space in Humboldt Park, Chicago. Moore’s solo exhibition A Vibe Called Death: The Black Afterlife is the culmination of many ideas he has been ruminating about since 2021, following the loss of seven family members. On January 1, 2022, he lost his grandfather, a wonderful man and father figure in Moore’s life. While Moore presents a heavy, autobiographical exhibition about death, the work also resonates as a celebration of Black life, culture, and nostalgia, with common themes including Afro-Futurism, arcade games, music, and 80’s pop culture memorabilia.

A Vibe Called Death: The Black Afterlife takes ownership of blackness too often perceived negatively in the dichotomy of good vs. evil. Moore explains, “Through Afro-Futurism, I determine how blackness can be used.” Chromophobia – a term that means the fear of color – manifests itself particularly in Western culture through many, varied attempts to purge color from society, devalue color, diminish its significance, and deny its complexity. Moore’s work confronts this prejudice through scale, color, sound, and the psychedelic illumination of glow-in-the-dark pigment under blacklight. Black bodies and black art are important aspects of Moore’s trajectory. White has become so commonplace in interiors that it often goes unnoticed. In a white-washed 21st Century, Moore’s use of fluorescent light and ornamentation embraces the bold. Large, loud, and buzzing with electricity, Moore’s installations disrupt the white cube through color while also drawing attention to the deaths of Black bodies. The artist feels it is important to address these specific deaths due to the systemic racial injustice in our country that leads to murder, including the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and innumerable others taken by the hands of those who have sworn to “serve and protect.” Countless Black women, trans women, and nonbinary Black individuals go missing or end up murdered every year with no justice served.

Within the work in the show, Moore also examines the relationship between church and African American culture, describing his work as having an adjacent relationship to church. Though not very religious himself, his uncle was an assistant pastor and certain memories from childhood have stuck with Moore, including his uncle’s favorite Bible passage, Psalm 1:27, “The Lord is my light and my salvation – whom shall I fear?” Moore describes visualizing three spheres of light while attending mass as a young man. The element of light (blacklight, colored LED light, and light projections) is present in Moore’s installations, which often cast color onto black surfaces.

Even before his losses this past year, Moore has sourced inspiration from childhood memories, early trauma, and a deep connection to music and family when composing visual art and experimental sound. Implementing a sense of personal history, Moore casts graphite records specifically recorded before 1987. Moore memorializes this era, which he views as a pivotal moment in his own life before his mother contracted a rare liver disease. Moore describes his childhood home as full of music, happiness, and life leading up to 1986. “Both our life and our relationship were just different after her diagnosis. She was tired all the time. She was heavily medicated. She slept most of the day. And I noticed a change in our relationship and my path. That’s why I wanted to reference music made before that time, before I had an eerie understanding of mortality.” Outside of his personal narrative, Moore views this era as culturally significant to Black culture. “I think of the 60s, 70s, and 80s in terms of Black music. Growing up in the 80s, that energy was there. I can relate to Motown, Marvin Gaye, Earth Wind and Fire, and I can remember how I saw it in the clothes, the way the living room was set up, the taste, the smell, and I know that I synthesized all of that in my own brain. That just seemed like a different era for me.”

Moore likes to play with his titles, whether it’s the rhythm and cadence of words with the same number of syllables that rhyme (A Vibe Called Death intended to sound like A Tribe Called Quest), or playing with numbers, letters, and palindromes (as with his performance and cassette tape recording Lived a deviL, with the uppercase L mirrored in devil). The second part of the title for his current exhibition, The Black Afterlife, also has a double meaning. The afterlife does not only imply a heavenly resting place, but also refers to Moore’s life after loss; as in, the life that he must now live in the wake of tragedy.

Trap Coffin, a major piece in A Vibe Called Death, is a clever play on words relating both to trap music and the metaphorical traps set in life. The sound sculpture is composed of a casket painted black with speakers incorporated on either side, resembling a box-and-stick trap. Moore says Trap Coffin references his experience growing up in a poor Black neighborhood. “The trap is that you can’t avoid certain things. You get sucked into traps sometimes just trying to survive. And then there’s the obvious trap of capitalism itself, or how systemically fucked up our country is. There are pitfalls, boundaries, and traps everywhere. So I decided to prop up the casket with a stick, making it a trap. I began thinking about pink being synonymous with trap music or the Trap Music Museum in Atlanta, so I painted it pink. It’s literally propped up by the stick, which makes it look like something that can easily be pulled to capture you, and you’re stuck. All of us have to escape as many pitfalls as possible no matter our race or gender. There are so many things out there that can hurt us, kill us, in whatever direction we want to go. Then, talking about death, there are a lot of people who did not escape. They got caught by the trap.” The musicality and red glow from beneath the casket of Trap Coffin evoke a siren’s call, while also bringing to mind nightlife from the Vegas strip to the red light district.

The prominence of red and blue light in Moore’s work represents America, cop cars, and the red and blue shift of stars. When looking at the night sky, some stars are moving closer to us, and others further away. When a star is moving towards us, the light is known as blueshift. When a star is moving away from us, the light is known as redshift. Moore relates these shifts to past and future; as the future moves towards us, we simultaneously move further from the past. “Red and blue can be symbols of multiple things. It’s nuanced. I take comfort in these colors, even with red and blue lights [from cop cars] being threatening to me and to my existence. I’m constantly being profiled on a daily basis. But I can compartmentalize those colors and those aesthetic qualities, and use them to reference anything I want.”

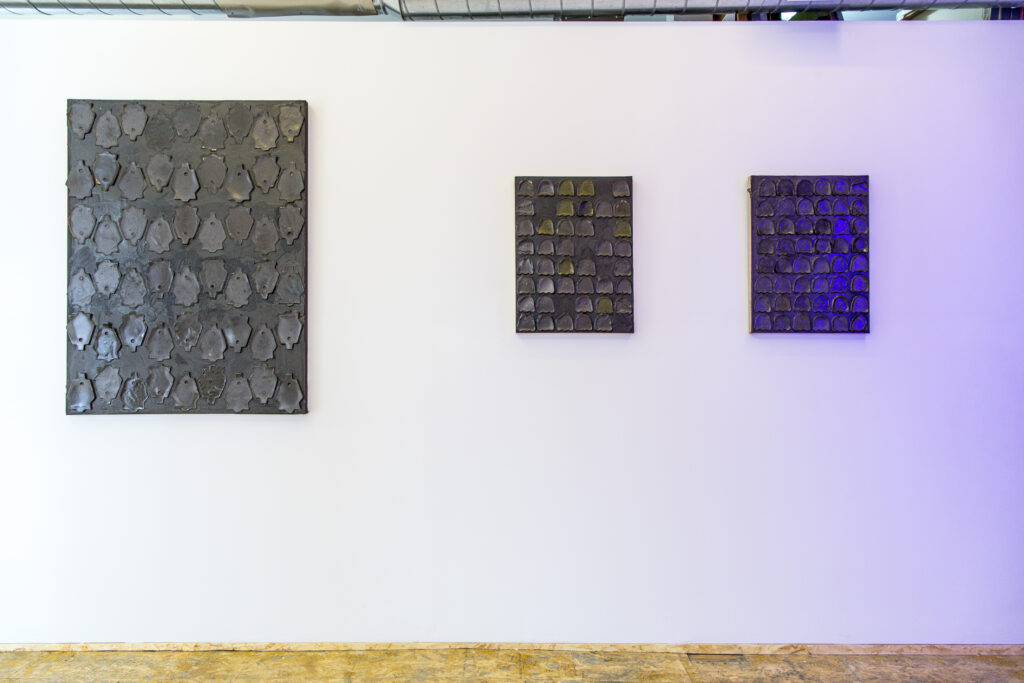

In A Vibe Called Death, two works of equal size hang together: Red Shift 41 and Blue Shift 48. Each painting is composed of graphite-cast Pac-Man ghosts arranged in a grid pattern across the black surface of the canvas board. Red Shift 41 features a grid of 41 Pac-Man ghosts with seven empty spaces. Moore was forty-one at the time of his grandfather’s death and had recently experienced the loss of seven family members. Forty-one is also the road Moore’s family used to take all the way to Atlanta before the expressways were built, making 41 the literal path from Chicago to their ancestry and family in Atlanta. Blue Shift 48 features 48 Pac-Man ghosts and references Moore’s grandfather’s age at the time of Moore’s birth. Additionally, the combination of the two numbers in the two titles, 48 and 41, equal 89. Moore’s grandfather was eighty-nine at the time of his death.

Continuing with Moore’s connection to numbers and patterns, his assemblage-style painting Solar Eulogy features a pattern of 54 graphite-casted geometric shapes on a panel painted black. The shape is recognizable to vintage toy collectors as the packaging for the Masters of the Universe action figure Skeletor, the main antagonist of the Masters of the Universe franchise and the archenemy of He-Man. Masters of the Universe aired from 1981-1988 and served as a comfort to Moore during times of familial trauma. The number 54 is significant to Moore, as his grandfather was born in 1932; 54 + 32 = 86; 1986 being the genesis year for Moore coming to terms with mortality due to the onset of his mother’s illness.

In the gallery’s front window visible from the street is Moore’s 40 x 60 inch photo titled Black Trinity. The piece is a photo of three charcoal and resin-cast Pac-Man ghosts lined in a row, staged and photographed under blue and red lights. Each ghost has a distinct texture and coloring, though cast from the same mold. The ghost on the far left has a slight blue hue cast from the blue light. It is easy to identify its two circles as eyes and a squiggly line for its mouth embossed onto the surface. The same simplified facial features can be seen in the center ghost, but it is more difficult to observe because the object is darker in color since no colored light is being cast onto its surface. The final ghost is smooth, darkly colored with lighter patches and a reddish maroon hue that comes from the red light. Reading the imagery from left to right, the work may appear like a timeline showcasing the continuation of one’s journey from life to death, reminiscent of Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych. The blue ghost, like the blue shift, is coming towards us, born into life, while the red ghost is moving further away, dying, which may also explain why the face is missing.

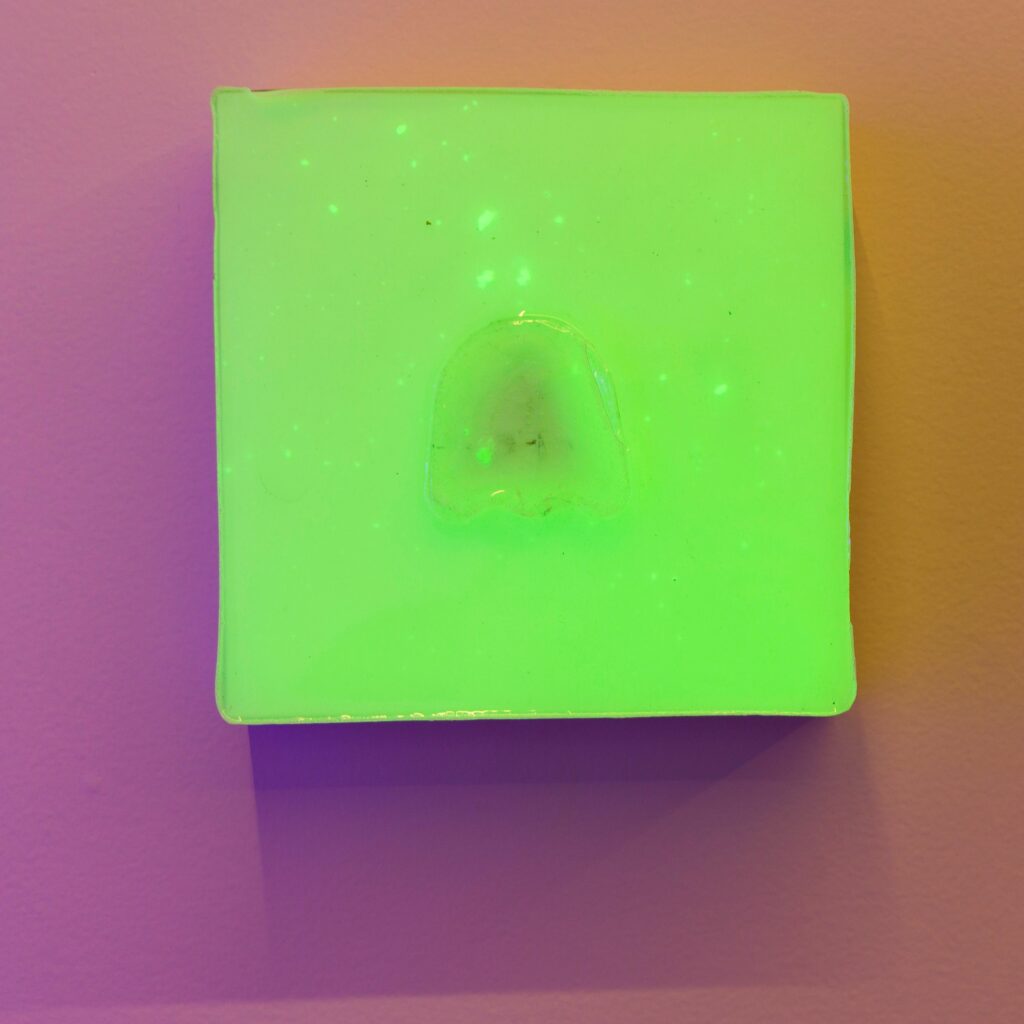

Moore’s Pac-Man motif continues in Annunciation, a multimedia painting featuring three graphite-casted Pac-Man ghosts encased in resin and adhered to the surface of a glow-in-the-dark pigment-covered board. The use of the triptych references the holy trinity and the metaphysical trinity of mind, idea, and expression. Graphite colors the ghosts black, which makes them recede visually when viewing the glowing structure. The contrast creates a silhouette outline of the ghosts, representing mystery and the unknown. Graphite is a recurring medium in Moore’s sculptural works. As a derivative of carbon, it plays a role in the building blocks of human life. Moore explains that his use of graphite is essential and universal. His use of the medium in both traditional and non-traditional ways transcends the material beyond its predictable margin. Moore’s work titled One for Ghost features another glow-in-the-dark pigment-covered board with a single clear resin-cast Pac-Man ghost at its center. However, this ghost is more difficult to identify due to it being transparent against the glow-in-the-dark pigment.

Using Pac-Man ghosts as a recurring motif relates back to the artist’s large-format photo Ghost Tales, made from Moore’s childhood portrait taken while playing Ms. Pac-Man on an arcade machine in 1991. Moore scanned and blew up the photograph to near-life size proportions and housed it in a unique custom frame. The frame was fabricated by Cleaner Gallery’s director Ryan Burns who also fabricated the casket in Trap Coffin. The frame is part of the art itself, made to look like a funhouse mirror. Moore painted the frame black and modified it with LED strip-lights so it is backlit with blacklight. The artist explains that the photo was taken by his godmother, just a year before her son was murdered – another pivotal time in Moore’s life. The picture captures Moore as a prepubescent boy, “embarrassed by his short shorts and tall socks,” wearing a Sox hat and an innocent smile. The jagged black frame encapsulates the image, both playful and ominous.

Moore is a self-proclaimed nerd, and a huge fan of eighties and early nineties cartoons, including The Real Ghostbusters – the animated television series spin-off of the 1984 film, which aired from 1986-1991. Moore described the blockbuster hit as something his entire family loved. This led him to buy a replica Proton Pack (a fictional, energy-based device used for capturing ghosts) during the pandemic, with the intention of turning it into a record player. Moore recalls how it felt watching Ghostbusters as a kid and experiencing the positive impact of Black representation in film and media. The character Winston Zeddemore, played by Ernie Hudson in the film and originally voiced by Arsenio Hall in the animated series, served as an inspiration to Moore and his cousins at a time when there weren’t many Black characters portrayed in children’s media. Moore’s Proton Pack Record Player pays homage to the importance Winston Zeddemore played in his childhood, while also addressing the afterlife and ideas surrounding the metaphysical through the context of capturing ghosts. Moore’s piece Charon’s Coin, a clear resin-cast Pac-Man ghost with a “heads-facing” quarter at its center, also references an afterlife icon: Charon, the Greek ferryman of the dead who demands coin currency to ferry unliving souls across the River Styx. The quarter is also indicative of the coin-operated arcade machines of Moore’s childhood.

Moore’s exploration of a Black afterlife rejects the typical imagery associated with heaven, such as following the “white light.” Instead, his vision favors red and blue hues that represent shifts in past and future. The use of blacklight and red LED light draws predominantly from 1980s and 1990s science fiction, video games, and cartoons that saturated Moore’s childhood. Additionally, blacklight is a combination of spectral colors close to purple, a color that denotes royalty, magic, spirituality, and the divine. The lights serve as an empowering dystopian aesthetic both reminiscent of the past and representative of the future. Moore gives prominence to materials like graphite, glow-in-the-dark pigment, and blacklight, creating a neon atmosphere that cultivates ethereal contrast within the space. The vibe called death is very much the neon hues of Afrofuturism – a hopeful way forward into the Black afterlife.

A Vibe Called Death: The Black Afterlife exhibited at Cleaner Gallery + Projects from March 11 – April 9, 2022.

Allen Moore asked that I share a special thanks to his partner Christina Warzecha, gallery director Ryan Burns, documentation photographer Amy Shelton, and myself (Lauren Iacoponi). Moore is especially grateful to Warzecha for her love, patience, and support during the hardships of loss.

Lauren Iacoponi is an artist, curator, writer, and arts administrator living and working in Chicago, IL. Iacoponi received her MFA from Northern Illinois University with a Certificate in Art History and her BFA from Columbia College Chicago with a Minor in Art History. Iacoponi is the Director and Founder of Purple Window Gallery, an artist-led project space coming soon to Avondale and the Director and Co-founder of Unpacked Mobile Gallery. Instagram handle:@lauren.ike