Featured image: Shannon Finnegan, Do you want us here or not?, 2018, MDO, paint. Blue wooden bench in a gallery with text painted on it. The back of the bench reads, “This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long.” The seat reads, “Sit if you agree.” Image courtesy of the artist.

It’s a sunny but below freezing Saturday, the sun reflects harshly on the snow that is left behind from the most recent fall, making me squint as I wait for the 60 Blue Island bus. My anticipation grows to see the space and work, plus the possibility of warmth. Sometimes gallery spaces can be so cold, literally and figuratively. Exiting the bus, I yell “thank you”, a habit I doubt I’ll break. Precise plowing mixed with a heavy layer of salt, the sidewalk illuminates the route to the gallery.

Entering the building I see a clearly marked accessibility path and I am relieved as I round the corner and notice stairs. I myself am able bodied, but this very basic access need is overlooked by most, if it is even thought of at all. I climb the steps to Gallery 400, self conscious of the black sludge I will drag in, and am greeted by the gallery assistant. They ask to view my vaccination card and inform me where to access plain text and audio recordings of the gallery materials. It is of no surprise that this show is on top of providing access needs, which are a form of acknowledgement, care, accommodations, and desires that allow people with disabilities to be included.

Crip* is a group show of artists who either identify as disabled or relate to a non-normative identity. For those who need it, the Wikipedia definition of crip, slang for cripple, is a term in the process of being reclaimed by disabled people. There is a lot to unpack there, including the disability rights movement, crip theory, and disability justice, which I’m sorry to gloss over in this review. If you haven’t already, I suggest investing some time into these topics and read work by disabled authors to inform yourself on disability justice. To help open up the conversation, I’ve included some resources at the end of this review.

The energy in the exhibition space buzzes with pride, celebration, vulnerability, and reclamation. It can easily over stimulate, but so much of this work asks you to pause, rest, and breathe. My eyes are immediately drawn to the film by Brontez Purnell being projected onto the white gallery wall. However, two other visitors are sitting and watching the piece, so I continue to move through the space, noting to come back. My first pause is at Max Guy’s pieces titled, I’m a Game #1 and I’m a Game #2, two tables in the shape of a person’s silhouette with grids on top and game pieces laid out in specific configurations, but also separated into piles. My board game-loving self wants to know, how do I play? What is the objective? There are no instructions and it seems that the intention is for visitors to not “play” the game that the artist has placed in front of them. Perhaps the artist’s titling lends to how he might feel while trying to navigate his body. How the right pieces in the right places could allow them to move, function, and thrive through the day.

Pushing myself away from the temptation to play, I am confronted by a bright blue and white bench with text on the back that reads, “THIS EXHIBITION HAS ASKED ME TO STAND FOR TOO LONG,” while the text on the seat reads, “SIT IF YOU AGREE.” Shannon Finnegan’s piece, Do you want us here or not? functions as usable and it felt good to know that there was at least one place to come back to sit and rest if I needed to. As the artist posits, many institutions and galleries lack places of rest, which can make the art viewing process exhausting and laborious — like trying to make it up a hill that never plateaus.

I get giddy when I see zines laid out on another bench nearby, Liz Barr’s zines Body Works and Conditioner lay waiting as I glide over, antsy to thumb through the pages. I start with Body Works, making some assumptions that it will be about the female body based on the cover image. My assumptions were correct as the creator of the zine opens with a reflection posing a lot of questions that I myself have also been pondering lately, such as, “What do I want to look like and why?” and, “What cultural forces shape my own perception of my body?”.

Please pause and reflect on these questions for yourself if it feels right.

Here, an examination of beauty and the roles it has played in our conscious and subconscious collides with how society has simultaneously pedestaled desires of “natural beauty” while downplaying the labor involved to achieve that “beauty”. The other zine by Barr, Conditioner, reflects deeper on topics of shame, aspirations, and healing within ourselves and our bodies. The last sentence reverberates the tone of the zine: “I want my body to feel more like a gift and less like a burden.” I cut my reading time short as I feel a small wave of tears trying to part ways; these topics resonate to my current personal journey. So I scan the QR code to read, reflect, and cry later.

My knees pop as I stand up from the bench and turn to view six large framed drawings by Emilie Gossiaux, which have some of the best titles in the show: Arm, Tail, Butthole, London Mounting the Couch, and London in the Presence of the Goddess. There is a clear connection between the dog (London) and the person (Emilie Gossiaux) that is depicted in all of the drawings — a companionship. The fast gestural crayon marks along with the hard indented ballpoint pen lines supply the drawings with this lush, textural quality that makes me want to graze my fingertips across the surface. Gossiaux allows you to be a voyeur into the interdependent relationship she shares with London, allowing you to be included in their intimate moments and memories. At the end of the room London patiently waits for you on hind legs, not in her golden glory depicted in the drawings, but in a shiny gray stone-like material instead. She is inviting you to dance, share a moment with her, be a companion.

Nearby, monochrome amorphous plastic shapes lay on the ground connected to cords and power strips; a soft wheeze draws me closer to the objects. Plastic-celled mattresses corseted in different braces try to adjust to be comfortable, slowly inflating to tighten in the brace and hold their posture, eventually deflating and slouching down. In this installation by Berenice Olmedo, titled áskesis, a shifting duel between comfort and discomfort is present, one where discomfort seemingly wins more often. Why do objects that are “designed” for assistance so often disregard the comfortability of the person using it? Holding and sitting with discomfort is an exhausting space to occupy, one that is amplified when it is your body that is the source of discomfort.

I’m pulled from my thoughts of discomfort in bodies by violin noises. I get the annoying feeling as if I know what song is playing but can’t place it. A nest of haphazard black cords cradle a circle of bright yellow violins, reminiscent of birds in a nest calling out. I sit and close my eyes, the back and forth of vocals and violin replaying in my head as I try and piece together what song it is. I give up on the battle and read the title card, PureImagination_Sextet by Christopher Robert Jones, the song in question is “Pure Imagination” from Gene Wilder’s ‘Willy Wonka’. “Want to change the world? There’s nothing to it.” During this pandemic, I think a lot of us have thought about how we want to reshape and change the world we live in. Access needs were put into place that disabled people have been asking for for a while, but as the ableist capitalist world continues to want to move forward, those access needs are slowly disappearing. How can we sustain change in the world that centers the disabled experience and continues to prioritize access needs?

My eyes shift and find relief in the dimly lit room next door, where scenes from Alison O’Daniel From the Tuba Thieves play. I take a seat on the bench, and the battle begins between the intended lower sounds in the film and the loud furnace spewing out warmth. I’m able to experience a ‘hearing-loss’ that aligns itself to the artist’s methodology. I rely more on my eyes to take in the surroundings and captions if they are present, but also lose out on information that is not audible for me. A slow, close-up scene of a person getting into a truck in the pouring rain illuminates the wall while the narrator gives audio descriptions. I’m engrossed with the supple imagery O’Daniel creates through the two pieces, engaging and slow, giving you time to explore the surroundings and its details.

I squint and my eyes adjust as I transition from the dimly lit room to the harsh fluorescent white space next door. A screen inside of a white frame is leaning against a wall, with a 3D sculpture of a male body resting on top while the screen displays a male body that is constantly circling on a pedestal. The piece, Contrapposto by Darrin Martin, is a representation of this term: a figure standing with most of its weight on one foot while the other is slightly bent. On the screen, block-like structures start to encapsulate the body, blurring the body with material. The screen glitches and the body regenerates, the block forms either being more or less prevalent around the body. Do the blocks provide something for the body or are they taking something away?

Image: Darrin Martin, Contraposto, 2016, HD video 16 min, 3D printed sculpture, sculpture 10 x 3 x 4″, shelf, 40″ monitor. The photo on the left shows a front-facing view of a white sculpture of a man standing on the edge of a white frame. Inside the frame is a video showing a silhouette of another person standing. The right image shows the same installation, but from a perspective that shows the side of the piece. Images courtesy of the artist.

Sharing the fluorescent white space are two sculptures by Carly Mandel. Her first piece, titled XXL Medical ID, consists of two U-shaped silver bars mounted on the wall; one U holds a jagged glass-like ball with white shards inside, while the other U holds an oversized medical ID bracelet. The second sculpture, Arm Exerciser, uses an old shoe store bench (the ones with the mirrors on the side) as a display surface for a metal and clay beaded chain. At the ends of the chain are silver handles, one resting on the bench and the other hanging off the side. The silver and mirrored objects in both of the pieces catches and reflects the sun coming in from the large window. Streaking yellow and white monikers on the gallery walls, leaving impressions on the inside of my eye lids. Both are giving off a high fashion energy, like, yes, I will take this ‘XXL Medical ID’ and wear it as a belt or a sash. Get the clay beaded ‘Arm Exerciser’ — it is the perfect scarf for spring!

Since I can’t walk away with the hottest new accessories for spring, I slowly make my way back to the front of the gallery space, scanning the rooms and their contents one last time. Entering the main gallery, I notice the two other visitors have moved, so I walk over to view Brontex Purnell’s Pillow Fight. In the video, two people, one Black man and one white man, are jumping on a mattress having a pillow fight in a variety of urban city environments. What seems to be a power exchange unfolds between the two throughout the piece, then a pause, and an embrace. The final image: pillows crumpled on the mattress. The body language between the two people feels playful at points but also has the potential to quickly shift to aggressive. There seems to be a lot of unresolved strife between the two throughout the video, resulting in a parting of ways.

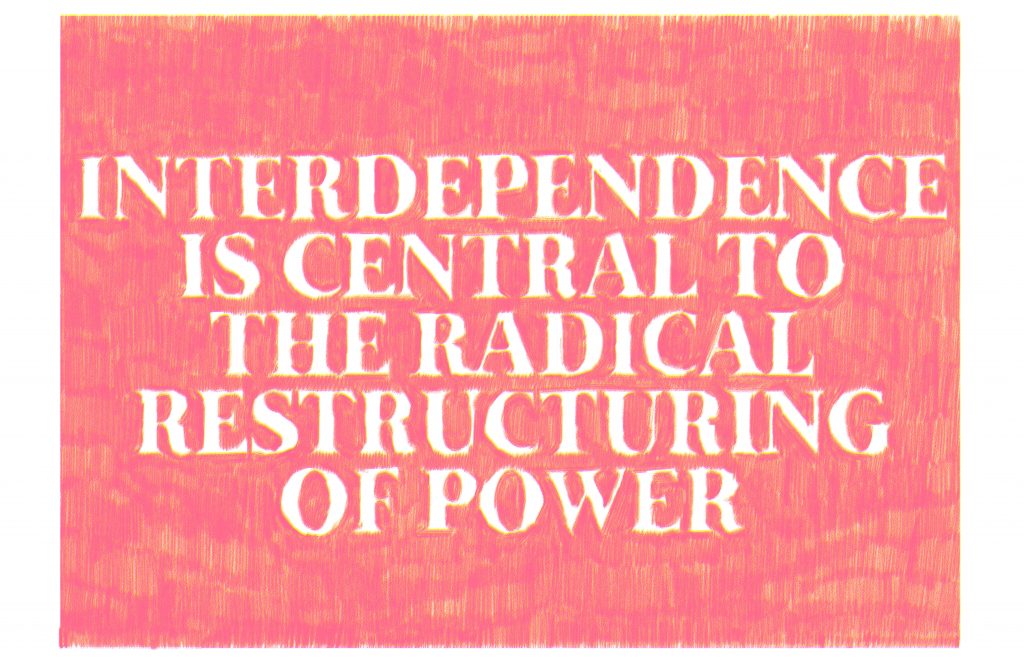

Before leaving the space I see a short pedestal with a stack of risographs by Carmen Papalia and Heather Kai Smith, with a display that encourages visitors to take one. The front of the piece reads its namesake: “INTERDEPENDENCE IS CENTRAL TO THE RADICAL RESTRUCTURING OF POWER”. This statement resonates with me as I try to be more interdependent and less independent in my own life. I believed for so long that being completely independent was the best, but I’m learning how it’s not super helpful. I am a care worker for someone with a disability, and I have a sibling who is visually impaired. Interdependence wasn’t but at the same time is a new concept for me, I’m just now acting on it from a more honest place that doesn’t negate my needs.

The back of the risograph reads: “Open Access is a temporary, collectively-held space where participants can find comfort in disclosing their needs and preferences with one another. It is a responsive support network that adapts as needs and available resources change.” Similar to a mycorrhizal network, which is a mutual symbiotic relationship between fungi and plants, resources are exchanged throughout the network based upon needs. There are moments, more often than I like, where I feel like a burden and feel paralyzed to ask for help, feeling my needs and preferences aren’t as important as others — obviously my logic is very wrong. Interdependence asks for us to be vulnerable and honest in the naming of our needs and preferences, which can be hard at first. Creating collective and open access allows for us to come together to facilitate the support networks, or pods, we need to exist/survive.

I say “thank you” as I leave the gallery to descend the stairs, not wanting to go back out in the cold and the harsh sunlight. I figure out the commute route and wait a short amount of time for the 60 Blue Island bus again. Greeting the driver and heading to the back, my thoughts are jumbled. Art has and is a way for us to tell our stories and the artists in exhibition all had a different and diverse story to tell. I recognize that the pandemic times have been hard for a lot of people, but it has been harder for people with disabilities and immunocompromised folks. As mask mandates lift, access needs disappear, and capitalism continues to push its ableist agenda, we need to believe in the disabled future.

We can continue to work against that system of oppression by centering the disabled experience and providing access needs at the base level. Disability justice is practical, it can even contribute to your able-bodied experience, but it requires us to center and prioritize those who have been heavily excluded. So, yeah, your state or city may have lifted that mask mandate, but you can still require masks to be worn at the events you put on. Disabled people have been, and will continue, keeping each other alive and we need to amplify their experiences, wisdom, and frameworks. A final question to reflect on if it feels right for you: how can you expand upon the mycorrhizal network to further support others in your own communities?

*Crip was on view at Gallery 400 from January 14 – March 19, 2022.

Resources:

Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Disability Visibility edited by Alice Wong

Expanded online resource: https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/

Criptiques edited by Caitlin Wood

Sins Invalid (a disability justice performance project)

Leaving Evidence by Mia Mingus

Disabled Parts edited by carrie sarah kaufman

Ashley Ariel currently makes and grows things in Chicago, IL.