This interview has been edited for clarity and length, and translated for our readers in Brazil. Leia este artigo em português.

Inaê Moreira: Hi Alexandria, pleasure to meet you! I’m an artist from Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. I work with body arts, dance and performance. Through my work I have been investigating issues involving ancestry and Black memory. I would like to know what you have created in this field: Black body, ancestry, memory?

Alexandria Eregbu: Hi Inaê! There are several works throughout my practice which address the Black body, memory, and ancestry. From a materiality standpoint–one of the primary reasons I began working with indigo dye came from my curiosity to learn more about Black people’s contributions to textile history. This history was not one that was acknowledged during my time in art school while studying fibers, or artmaking period for that matter. Intellectually, I wanted to immerse myself in more resources that addressed West Africa’s connections to cloth and performativity as a means to better inform my understanding of cultural and traditional activities taking place in African diasporic communities in the United States. Growing up, I was often among women who sewed, embroidered, made quilts, and furthermore loved to adorn themselves in colorful, shiny, and textured fabrics like tie-dye or wax prints. Like a child, I wanted to know more about their origins. So, I began digging.

What I have found is an enormously vast universe of rhythm, symbolism, language, and storytelling that is embedded into these fabrics from the continent. [I’ve found that cloth] serves not only as a mode of creative expression, but rises from a tradition of cultivating meaning and charging objects with both functionality and purpose. Much of my indigo dye work is an ode to that practice. The color blue is significant in its associations to water, the sky, collectivity, communication, and emotion. I often find myself activating memory and familial history through painting, drawing, photography, and performance, and as a means to integrate knowledge generated from my maternal (American) and paternal (Nigerian) sides. I often think about the potentiality that objects carry to empower and remind Black individuals, families, and communities of where they’ve been as a means to fully acknowledge who they are. For me, the acknowledgement of my ancestors and those who came before me, plays a huge role in how I come to bear witness to myself and my creations.

She Who Carries Weight and Daughters of Mmiri are two projects that I feel especially highlight these things.

Can you tell me a little bit more about your relationship to dance? How did you find it or how did dance find you?

Inaê: To talk about how dance found me, I need to give you a brief introduction to my world. I belong to a Black family in the city of Salvador, Bahia. My father is an artisan and goldsmith who builds jewelry inspired by the tools of orishas, and my mother is an exceptional and creative woman who develops an ethnogastronomy project called “Ajeum da Diáspora” (Diaspora ajeum), a research endeavour on Black cuisine brought by African peoples that arrived here. I was raised in this context of creativity and autonomy, and art and spirituality underlie my existence. I grew up attending “terreiros de Candomblé,” or Candomblé yards, where cults to orishas take place, and in this sacred space I was nourished by the manifestation of enchanted beings that are deeply linked to nature. Dance is these beings’ channel of communication, they dance in the center of the yard to the touch of the atabaques, and to chants in Yoruba. That was my first encounter and invitation to dance.

I was fascinated with the idea of communicating through movement, establishing a connection between my ancestry and my spirituality. When I finished school, I went to university and graduated as a dance teacher. I did some training outside my city for seven years, but only when I returned in 2018 did I rediscover the true meaning of my work. Dancing did not mean developing virtuous forms, masterful technique, or learning choreography. Dancing is my link to my ancestors, my survival strategy and my healing space. That’s why, today, I am developing two projects that are important in this trajectory. The first one is called “Dança Intuitiva para Mulheres” [Intuitive Dance for Women], where I invite women, who aren’t necessarily dancers or performers, to find their own dance. I propose a space of healing and care to move and transmute the memories of oppression lived by our bodies.

The second project is called “TEMPO” [TIME], a performance where I seek to rediscover other understandings of time, revisiting the time of colonial trauma, and seeking healing time, asking how my ancestors understood time. In this piece, I create a burial and rebirth ritual with about 300 kilograms of sand above me. In Chicago, I performed with Black women from the South Side, and it was an amazing experience. I hope I have told you a little about what is going through me, and I can feel a lot of connection between our creations.

Given the trajectory I shared, I observe a common feature of our work, which is the Black memory in diaspora. Knowing your Nigerian descent, I would like to know if the theme of spirituality runs through your creations, and how?

Alexandria: Personally, I use spirituality as a means to connect with nature, my subconscious, and the cosmos. I think soulfulness and spirituality are two qualities that have run through me from my beginnings. I believe my material and environmental sensitivities are conditions I inherited from both my maternal and paternal sides and that these conditions have greatly impacted my spiritual practice. In my family, everyone loves to eat and we all carry the understanding that food plays a major role in our fellowship and ability to participate in community. We have our own recipes and share these memories amongst ourselves, calling upon the joys of our ancestors and our origins. We know that nutrition, where food is sourced, and ultimately prepared holds a great influence on our physical, intellectual, and emotional well-being. There’s a shared understanding to practice resourcefulness, letting “no food go to waste,” out of respect for the Earth’s continued generosity and the loving care placed on our food by the hands that prepared it. We do these things for the sake of self-empowerment, actualization, and sustainability.

This kind of consciousness is a tradition that has been passed down to me through generations of mindfulness and is most definitely energy I bring with me into the studio. I consider these elements as foundational resources that support me during my travels and help make me a better artist and storyteller. For this I am infinitely grateful because I understand that this knowing protects me during the most difficult and abundant of times.

Inaê: How beautiful. I share so much of these sensations and purposes. The experience I had in Chicago strengthened the spiritual dimension of my work. Analogous to how you view nature, the subconscious, and the cosmos, I feel that creative dialogues in diaspora always bring us new elements to deepen our spiritual and artistic fields. Close to There, in a country so far from mine, without speaking English, and even with all possible cultural barriers, I was able to meet other Black women, and experience a familiar sensation—in the gaze and in the touch. We perceived an ancestral heritage that connects us and is inexplicable. I was able to elaborate on the common loss that we carry with the history of slavery; an abyss, which is filled when we meet again anywhere on the map, and we begin to feel our inseparable bond, especially through spirituality. Considering these sensations, I would like to know what the experience in Salvador offered you in this regard? How did your Blackness manage to communicate with this territory? And your art?

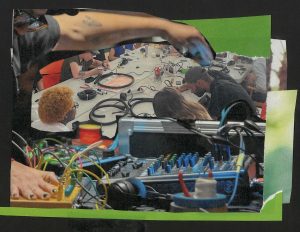

Alexandria: I love that you mentioned language barriers as a source for strengthening connection to spirit. I spoke of this sensation often with many of the Close to There cohort— reflecting on that tinge of frustration from not being able to connect the way we always wanted, but also how the warmth of a smile, laughter, touch, gesture, image, or song also carried the ability to transcend initial communication barriers placed between us. I think of Blackness as a great source for creativity and found myself quite enjoying the music and poetry generated to produce alternative pathways for communication during my time in Salvador. I had the opportunity to facilitate a tie and dye workshop at Casa Rosada amongst a group of women who primarily spoke Portuguese. I brought in a few books with visual examples of West African tie methods and also provided a demonstration on natural dye in collaboration with local Brazilian artist Aislane Nobre. I was pleasantly surprised by how naturally all of the participants took to the activities just after a set of minimal instructions. It was a great reminder of the power of both will and demonstration. Even though I could not always understand what was being said, I could see the joy in their faces and the commitment they had to completing their work over a 6-hour day. This meant a lot to me because it suggests that the space we shared together held both meaning and resonance—sentiments that feel harder and harder to come by under the heavily-saturated capitalist landscape that infiltrates much of the industry-oriented “creative” activity in the United States.

My personal interests in both Blackness and art-making have always been invested in the surreal. Salvador seems to have a lot to offer in this regard. The people are given a lot of freedom and liberty (from what I could see) to openly express themselves artistically, romantically, and spiritually. There wasn’t a single place I visited where I didn’t hear or witnessed graffiti, poetry, music, and ritual in action. These kinds of subconsciously-led interventions are highly regulated, if not banned altogether, in Chicago.

Thank you, Inaê for engaging with me in what has been a truly invigorating conversation. I hope we can continue to find ways to stay in touch and wish you all the best on your creative journey!

Featured Image: As part of “Perto de La <> Close to There” in Bahia, Alexandria Eregbu and Aislane Nobre led a natural textile tie and dye workshop at Casa Rosada, in Salvador, Brazil, on February 8, 2020. Photo by Marina Resende Santos.

Marina Resende Santos is a guest editor for a series of conversations between participants of “Close to There <> Perto de Lá”, an artist exchange program between Salvador, Brazil and Chicago organized by Comfort Station (Chicago), Projeto Ativa (Salvador) and Harmonipan (Mexico City) between 2019 and 2020. Marina has a degree in comparative literature from the University of Chicago and works with art and cultural programming in different organizations in the city. Her interviews with artists and organizers have been published on THE SEEN, South Side Weekly, Newcity Brazil, and Lumpen magazine.