This essay and interview was produced in conjunction with the event “A Discussion with Chicago’s Cultural Changemakers” presented by Chicago Collections Consortium in partnership with Design Museum of Chicago that took place virtually on October 26, 2021.

As someone who tends to have more questions than answers, design really is a wonderful and fascinating field for me. We can ideate solutions all day, but there will always be new thoughts, ideas, and experiences that push us beyond our current reality. There is always more to be unlearned, discovered, and transformed. As an events organizer turned product designer, I’m interested in how mindful design practices can be used as a tool to access more joy, ease, pleasure, connection, and liberation. What I question most is — as creatives — are we designing for power or to empower?

Designing anything — an event, an exhibition, a garment, an app, a building, a system — requires constant care and attention to updating it. A building isn’t finished when the last brick is set; it needs regular repair and a wholesome understanding of not only the technical structure, but also its environment, purpose, who occupies the space — there are many, many intersecting components. Everything is an infinite prototype.

In this field, you often hear the phrase “people don’t know what they need until you design it for them.” I think this underestimates the inherent agency that each person has access to. You are the expert of your life, not anyone else. No matter where you may be in life or how old you are, you are still the expert of your story, your habits, how you navigate a physical and virtual space, the pain you carry, and you are ultimately the one who knows your dreams and desires best. Assuming otherwise can easily spiral a designer into a hero complex, piloting into a community they have little to no ties with and take on the role of a fixer-upper who incites more harm than actual good. It upholds toxic, capitalist ways of thinking where we are conditioned to believe that someone else knows your needs better or has power over your truth. Instead of designing for users, we need to be designing with people.

On October 26, 2021, three founders of different local design studios — Paola Aguirre of Borderless Studio, George Aye of Greater Good Studio, and Christopher Rudd of ChiByDesign — met for a virtual conversation on designing for social and cultural change within Chicago’s communities. Moderated by Tanner Woodford, founder of Design Museum of Chicago, the virtual table talk organically turned towards a designer’s relationship with the communities they serve, ultimately advocating for more collaborative methods and inclusive design thinking.

Chris Rudd founded ChiByDesign in response to the lack of representation of Black and Brown designers working with Black and Brown communities. As an academic, Rudd has often spoken out against the human-centered design process for its narrow format and negligence towards social responsibility. Pivoting away from a linear process, the ChiByDesign team brings together Black and Brown designers to use an anti-racist, trauma-informed ethos rooted in co-designing with their clients.

“When I started the studio, it was really about how do we bring together diverse voices to address these social problems?” Chris said during the talk. “We’re really focused on multi-level interventions that address racist inequities and systems.”

During one of their most recent projects, ChiByDesign partnered with the State of Ohio’s Department of Job and Family Services to “investigate how and why Ohio’s children services system disproportionately impacts Black and mixed-race children and families, producing inequitable outcomes.” ChiByDesign teamed up with recently emancipated youth who had experienced the foster care system to lead interviews and invited foster children, parents, and staff members to be further involved in the research process.

This collaborative approach led to key insights that the state is now using as a launching point towards racial equity within the foster care system. While speaking on the project, Chris said it’s not about “just identifying pain points in the system or service, but specifically how racism harms Black, Brown, and Indigenous children and families in the system.”

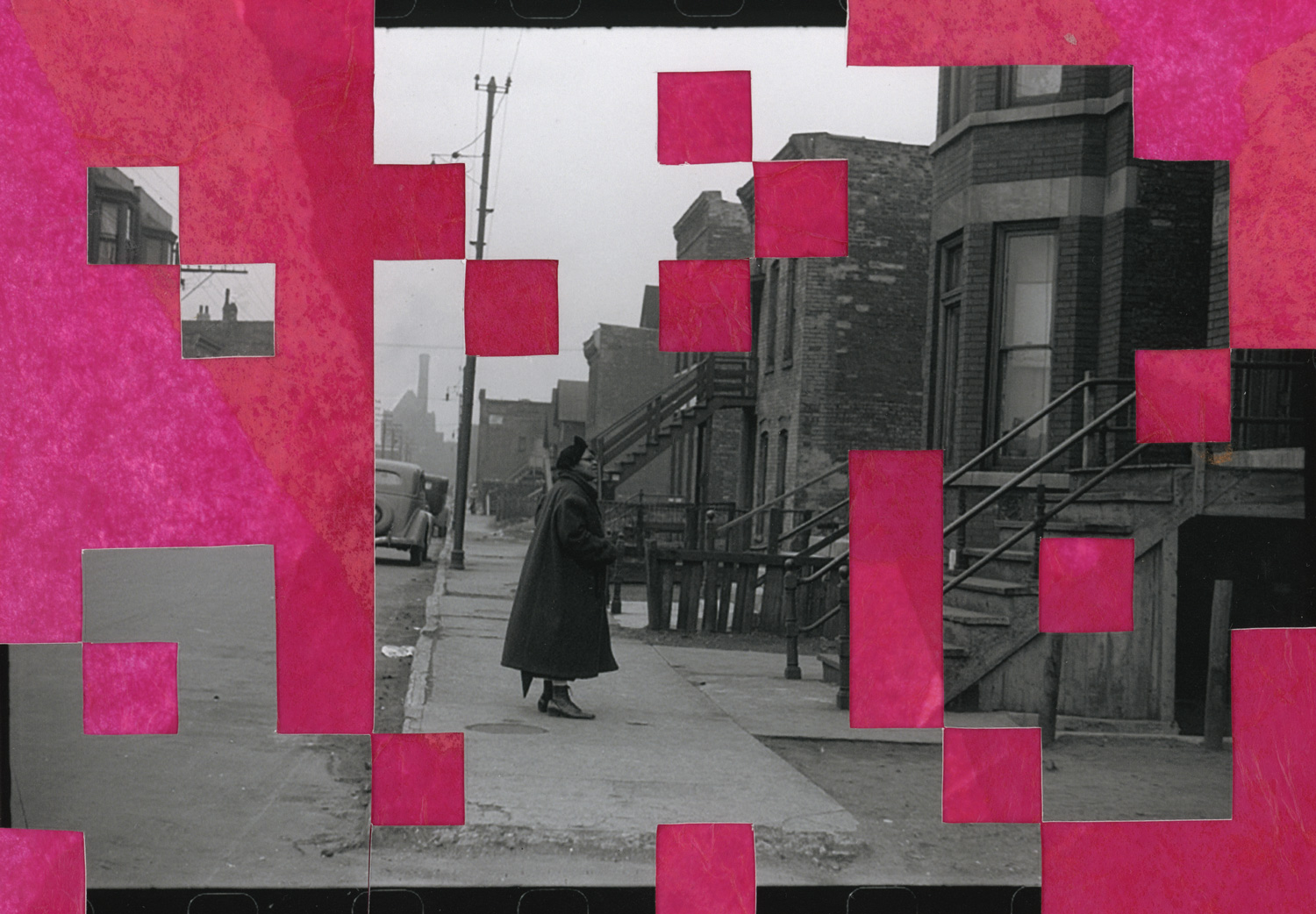

. United States Illinois Chicago, 1911. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016802472/. Illustration by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

What is so significant about this panel conversation is not only the keen focus on a designer’s responsibility to the communities they serve but also its innate ties to place.

“It is difficult to not be in Chicago and not still be feeling the echoes of major historical events,” said George Aye, Co-Founder of Greater Good Studio, during the panel conversation. “To do work in the social sector, how could [designers] not be entrenched in historical decisions that have long lasting effects that really reveal a lot about both the ways which harm was perpetrated, but also on our own unwillingness to recognize the harm that was done then and is still happening now?”

Having recently celebrated their ten-year anniversary, Greater Good Studio fosters a collaborative environment that values unlearning traditional design methods to instead apply a more holistic approach towards inclusivity in social change. The team of “pissed-off optimists” has focused on a wide range of equity-centric projects within Chicago’s arts and culture sector such as collaborating with Imagine Just to identify current power structures and reimagine the arts as anti-racist and an accessible resource.

“The adaptability of design to work in complex social issues is what we want to demonstrate,” George said. “I think there is a lot of utility in thinking about design and the design process in a lot of very deeply seeded systemic issues and many which are actually framed and very much controlled by the history of the context in which we do that work.”

“I believe that everyone has this capacity of transforming their built environment,” said Paola Aguirre, architect and founder of Borderless Studio. “I reflect on that all the time, like what are the barriers that we have constructed as professionals to separate ourselves from others?”

Breaking away from the hierarchical power dynamics typically found in architecture, Borderless focuses on collaborative design to “address the complexity of urban systems and social equity by looking at intersections between architecture, urban design, infrastructure, landscape, planning and civic participatory processes.” Creative Grounds, one of the studio’s research initiatives, explores how art, design, and architecture can be utilized as a tool for inclusivity when repurposing closed school grounds. What began as research into the closure of 50 Chicago public schools in one year, Creative Grounds functions as an interdisciplinary, holistic community project. Their work at Anthony Overton Elementary School on the Southside is a primary example of Aguirre’s passion for building together with community members to reimagine and reclaim their neighborhoods.

After the panel event, I followed up with Aguirre to debrief. Below is a snippet of our conversation where we dig a bit deeper into some points that came up during the round table discussion. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

NP: I keep reflecting on the part of the talk when Chris [Rudd] brought up if we can actually build a radical system while still living in a capitalist world. How do you begin to think about designing something that is new and inclusive when it still exists within the structure of capitalism?

PA: It’s hard, right? Because we all operate under this system. I think, all in all, that talk made me reflect on privilege in what voices get to be at the place of decision making processes, and that’s where I work a lot. How do you make space for a collective decision making process? And sometimes even when you create the spaces, people don’t know how to be a part of that conversation. I think a lot about the idea of shifting power and how to, you know, run conversations and facilitate with another type of leadership and really stepping back from all our types of practices.

NP: It’s interesting to evaluate hierarchies in design because there are several decision makers that speak and act on behalf of others. I think a lot about this in relation to George [Aye] also questioning who design has underserved but also overserved throughout history. How do you interact and engage with the communities you’re working with? And what does the actual process of that look like?

PA: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about laying out the framework of the design process. It doesn’t have to be super detailed or have set structure, but there are going to be moments in which we need to make decisions together. If there’s a project going on or something that needs to get implemented, there’s milestones, right? Like where things can be talked about, defined, talked about, defined…I’ve been thinking a lot about how to create tiers of engagement because all of us have a different capacity or relation to the project.

NP: How does documentation fit into all of this?

PA: I think intuitively I was interested in, you know, after we experience something together, what is that? Does it change anything? Does it contribute to the work that people are already doing? Does it amplify or connect people to their own power? What does it do? We started doing these interviews at the end of projects, primarily for Overton, where we wanted to capture that narrative. A lot of people I work with have such wisdom. And again, going back to the expertise right on this idea of separating ourselves through our professional degrees and all that separation, especially from young people, has been fascinating to me.

Noëlle Pouzar (she/they) is a product designer, writer, and creative strategist based in Chicago, IL. Through her art and design practice, Noëlle often explores how technology intersects with queer identity, accessibility, pleasure, and community. She holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Fine Arts and Writing from the School of The Art Institute of Chicago. Since then, Noëlle has received the 2018 Creative Writing Fellowship from the Luminarts Cultural Foundation and became a Community Leadership Corps Member at the Obama Foundation. Noëlle is also the Co-Founder of Monarch Art and Wellness, a public program initiative highlighting Chicago-based art and wellness creatives, small businesses, and resources for queer and non-binary communities. Visit Noëlle’s website here.