Movement Matters investigates work at the intersection of dance, performance, politics, policy and issues related to the body as the locus of these and related socio-cultural dialogues on race, gender, ability and more. For this installment, we sit down with artist, curator and DJ Allen Moore to discuss his part in curating a new monthly performance series at Comfort Station, the influence of music’s visual culture on his work, and organizing art for resistance in Trump’s America.

Michael Workman: You’re coming out of a multidisciplinary background, working in visual art and DJ’ing, and recently you’ve been working a lot with Comfort Station in Logan Square.

Allen Moore: Yea. I got in touch with Jordan Martins in early fall. They were looking for a group of people to not only curate, but to volunteer. I applied, talked to Jordan, and a group of us got together and started doing it. It’s been a really fun time. We’ve been slated to curate throughout 2017. We just had a show called Gather and we’ll all have some of our work there, too. We’re really focussing on how to make [Comfort Station] into a very open space. We’re still discussing it. We know that we really want it to be political, especially right now, but at the same time not be too heavy. We don’t want to hit anybody over the head.

For me, as an African American [artist], [politics have] completely influenced my work. And at Comfort Station, we want to have it open to [everyone]. We just had a workshop for making protest banners–I got to make one.

I grew up in Robbins, Illinois, which is a small black town. There weren’t a lot of expectations for me coming up through that. Now, fast forward and think about Donald Trump becoming President—

MW: I don’t even want to think about it.

AM: I don’t want to think about it either. It’s like night and day but…having to try, as an African American, to navigate bodies of work that talk about [the election] as organically as possible and also navigate my own [interests]. Not to say it’s [only] my own interests, but sometimes it flows together and we [feel a] responsibility of, “Oh, I have to do this.” I think we’re facing that at Comfort Station. We’re thinking about that [responsibility].

MW: Yes, and Comfort Station is in this communitarian tradition of domestic or alt-spaces in Chicago where you can perhaps present more politically-charged work whereas more commercial spaces might shy away from it because it’s bad for business.

AM: Exactly. I think the way we’ve come into it has been a good thing. We [recognize that we] should talk about the social and political stuff and the rights of individual people. We had our first show not to test the waters, but just to get it down. We don’t know if we’re going to stick with the title of the series, Gather. But we might. We just want to keep trying to find performers and cross-sections of art from sound, visual, and all sorts of things that show the conversation. We want to encourage people to [see Comfort Station as] a place where people can talk and be honest about what’s going on.

MW: Right. It’s a climate where a lot of the people who are taking power are clearly bigoted, and are creating this environment of encouragement for people to act that way too.

AM: Encouragement, entitlement….

Right now, my money comes from working in Glen Ellyn, Illinois. I’m a manager at a wine and sip place called Bottle and Bottega–as horrible as it sounds. There, I’m dealing with various entitled people—whom are everywhere. But I remember the night that Trump won. There was a party in where I work and I was like, “Yep, that’s exactly right.” And it’s just interesting the words that you hear. I had a woman come in who was friends with the owner and talking about African Americans—first of all, she was working for a non-profit to help kids from the inner-cities, which is great, but with the way that she framed it, somehow the conversation went to black fatherhood and how we, [black people], do it to ourselves.

MW: What? It infuriates me that people dismiss how much language actually matters. She might have just have said “those people.”

AM: She probably did. But then I had to sit there and serve this person.

MW: That’s demoralizing. So, Gather is about getting people together in the same place to talk and discuss these kinds of experiences.

AM: Exactly. In the same place and where we can feel comfortable. We want to grab [inspiration] from experimental sound; I think everybody else in the curatorial group is all music, though I also have a Master’s in painting. The last [Gather] more painting and sound. I’m not going to lie, I’m not exactly—I don’t want to say trained—but I’m more of a 2-D person who organically found a way to incorporate my love of music [into my art].

MW: They’re all art forms.

AM: Yes, exactly. That’s my philosophy. And I think that’s all of our philosophies. We are looking at experimental sound, we are looking at something that might not necessarily have other venues [to house them]. We want to bring in people and thematically make sure we go over the intersections how the [themes are] all going to meet. We discussed shows that might [include] completely different practices or things like that. It’s interesting. There’s already a lot of representation of things like 2-D work in galleries and I think when Jordan brought it to us, he was very for Comfort Station being used as a space [for sound] because of its awesome acoustics. But also, we thought it would be a nice thing for people in the community to come see. So, that’s how we got on the track of having this be more of a performance space. I think it’s a good place for people. And you kind of have to be up front–and that’s what we want. We want it to be a place where people can perform, but also where people in the community who are just walking past can come to see something that they won’t otherwise see on a Friday or Saturday night. I mean, there’s a lot of shit to go and see out there.

MW: Right, so this becomes a little island of creativity in a sea of commercial options out there.

AM: That’s right. And if you don’t mind, I might just steal that one.

MW: Hah! It’s yours, take it. So this push for a political context, is that in response to a sense that there’s this revanchist potential for return to erasure? Of the dialogue getting watered back down?

AM: Yes—I think it’s all that. But it’s important to us that we come to it as organically as possible. I think in the current climate, all the things leading up to Donald Trump becoming president–you can’t avoid it. If you [tried], it wouldn’t work. And that would make it not as unique as we want to it be. But there are a lot of places and a lot of galleries that would be afraid—

MW: Right, it would hurt business.

AM: Right. And the only profit we want is profit for artists. You know, people give donations. Then, too, we’ve put together documentation for the work [for the artists]. And we’ve had people perform who may not be able to get documentation for the work. That’s something we can give the performers. We can offer that. So, we want not only to have this relationship with the community, we not only want to be honest and talk about a lot of the social and political issues, but we also [want to] create a venue where the artists can come, bare their souls and get something from it. With the donations, we just split it evenly and don’t take anything from it. I think that’s how Comfort Station has been, but we’re looking out now for more grants and that kind of thing.

MW: What has personally drawn you to this work? It’s your politics, of course.

AM: Yes. And also coming up African American in Robbins, Illinois, which I won’t get into. But it’s also my adopted attitude about people. I love working with people, even though we all suck at different times. But I do like people–artists especially. Coming into this I want to be able to be there and help people, but I also want to be a [positive] representation. Like I said about the music scene, I think back to that conversation with one woman that really sticks out. She said, “Oh, well people who are very talented and living in the city are still not the same as those who can work with formal composition.” I want to fight against that. I don’t believe that being prim and proper is necessary or the formal representation of music, sound, and art. I want to, hopefully, be a representation of that [expanded view]. I’m learning a lot in addition to what we’re putting out there. I’m also making a lot of relationships, which is something you want to do in any art form. You want to network. And if I can help build a venue for people, for performers and especially for people of color, that’s it.

MW: And performance within the Western canon has been such a white person’s field. Especially dance, but also performance art. And that’s clearly a problem.

AM: Yes. People of color are kind of funneled. I know I was funneled. Growing up African American, I was funneled either into football, rap, or some other sport. That’s what I think is a consensus for a lot of people. But there is so much more in life, so much more in art and, yes, there has been an over-representation of white—and definitely an under-representation of people of color. I know I’m the only person of color in the curatorial group, but we’ve had an open dialogue and think we’ve all come to that naturally. We want to open it and make it more inclusive of people of color, but we want to come to that organically. We want to open it up for all people and not be exclusionary in any way. The work that we look for and the type of experimental sound that we like has just worked out so far.

MW: And has that been influenced by your work at places like Experimental Sound Studios (ESS)? I know they’ve gone through a transition recently losing their founder.

AM: Yes! Lou Mallozzi. I had put in a proposal with them. I had the pleasure of meeting Lou and having him critique my work about a year and a half ago at ACRE. That was a really great experience. I got the chance to communicate and talk with him. Then, my first major performance within that form was at ESS. Before that, I was in Dekalb at NIU, so I did a lot of my work there. I had a studio there and the transition for me was sculptural. I was experimenting with everything, so when I started doing sound, it opened up this gigantic world and I didn’t know but as I was moving through it step by step. I was in a space of sound. It is the most natural thing for me and my work.

I knew that ESS was where I wanted to go, and I was very lucky to get accepted. The performance was amazing. I totally intend to record there more–as often as possible.

Growing up as kid, there was a time when my mom got very, very sick and had experimental surgery. She almost died. It was a very rare disease. She’s where the music comes from–my love of sound and the work with the graphite records. When I started drawing as a kid, I drew from record covers and record labels. I would just sit there and look at the typography of speakers because my mom had a nice Fischer receiver and record player. I’d sit draw George Michael or Wham! album covers. A lot of artists [learn that way]. They don’t know what they’re doing and they don’t get a lot of direction. I didn’t get shit from high school. For a while I had no clue about grad school or anything like that, but I was lucky enough to gravitate toward the right places and people. And that’s what we hope the conversations we’re hosting will be.

Please feel free to send questions, comments or tips to Michael Workman at michael.workman1@gmail.com. Each month, as part of the Movement Matters series, a live conversation on subjects raised in the columns takes place with interviewees and experts in the field. Please join the Movement Matters Facebook page for updates, archives of Facebook Live broadcasts of these discourses, and to join in on future conversations.

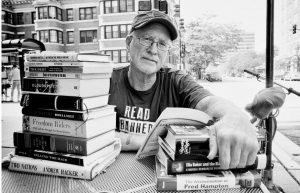

Featured Image: Portrait of Allen Moore DJing by Dan Mohr of Experimental Sound Studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

Michael Workman is an artist, writer, dance, performance art and sociocultural critic, theorist, dramaturge, choreographer, reporter, poet, novelist and curator of numerous art, literary and theatrical productions over the years. In addition to his work at The Guardian US, Newcity, Sixty and elsewhere, Workman has also served as a reporter for WBEZ Chicago Public Radio, and as Chicago correspondent for Italian art magazine Flash Art. He is also Director of Bridge, a Chicago-based 501 c (3) publishing and programming organization. You can follow his daily antics on Facebook.

Michael Workman is an artist, writer, dance, performance art and sociocultural critic, theorist, dramaturge, choreographer, reporter, poet, novelist and curator of numerous art, literary and theatrical productions over the years. In addition to his work at The Guardian US, Newcity, Sixty and elsewhere, Workman has also served as a reporter for WBEZ Chicago Public Radio, and as Chicago correspondent for Italian art magazine Flash Art. He is also Director of Bridge, a Chicago-based 501 c (3) publishing and programming organization. You can follow his daily antics on Facebook.