Featured image: India Sada reads from her poem “She Dreamed of Being Saved.” She stands in a dark room and is lit from an overhead soft-blue light. Her eyes are closed. She speaks into a mic. Image courtesy of Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project.

Mourning Racial Categories is a four-part series discussing four films that have been created as part of the Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project. This project engages the visual and performing arts to tell the stories of how people in the United States were divided into a handful of unequally valued racial categories, such as Asian, Black, and White. MCRC offers a language for the trauma suffered by our country, communities, and relationships caused by the formation of these categories.

The Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project (MCRC) was started by Joan Ferrante, professor of sociology at Northern Kentucky University. While teaching classes on race, Joan found that her students had a difficult time engaging in meaningful conversations about race even though they bore the weight of the classifications themselves. Academia alone did not offer students the language to unpack their relationship with their racial classifications, so she put together a team of students and faculty in the creative and performing arts to collaborate to create projects that would engage people with race.

* * *

In June of 2021, Why White? premiered at the 19th annual Cincinnati Fringe Festival. Why White? is the second of MCRC’s latest short film duology, the other being I’m White Like You Right Mom?. It is also the fourth film that MCRC has created, since it was founded in 2016. Why White? explores themes of religion and colonialism through the eyes of a veteran who is asked to check his racial category at a doctor’s appointment. The film opens with the following quote: “The world got along without race for the overwhelming majority of its history. The U.S has never been without it.”

These are the words of David R. Roediger, the Foundation Distinguished Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Kansas, where he teaches and writes on race and class in the United States. His novels include, Working Toward Whiteness and The Production of Difference: Race and the Management of Labor in U.S. History. These two sentences make a compact introduction to the film’s overarching themes and the lens through which this film was made. As of 2021, scientists know that there is no genetic indicator of race and that, according to the American Society of Human Genetics, humans cannot be divided into biologically distinct subcategories. Historians know that Carolus Linnaeus, the 18th century Swedish botanist and naturalist, can be credited with first introducing a basis for scientific racism with, 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae, wherein he divides humans into four subspecies: Europaeus albus: European white, Americanus rubescens: American reddish, Asiaticus fuscus: Asian tawny, and Africanus niger: African black.

That is not to say that the world was without colorism before the 18th century. But separating groups of people into subcategories based on skin color was at that point in history unique—and, of course, noting some as biologically inferior had economic benefits that U.S. imperialists took full advantage of. This is the philosophy that the United States was born unto and has therefore never been without.

After Roediger’s quote, the film opens onto a young, Black-appearing man. He speaks directly to the camera: “Since I was born and raised in America I’ve always identified as Black American.” What follows is a series of young men and women explaining their reasoning for checking the racial category that they do. They are all participants of the Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project; young men and women who are willing to unpack the intricacies of race and how it affects their day to day.

The same man says, “Part of why I don’t usually put Creole on forms is because most times when people think of Creole they think of a really light complexion.”

A white-appearing young woman says, “I don’t think I ever put any thought into it because I’ve just always been told you’re white by mom and dad. You’re white.”

Another says, “I appear incredibly pale skinned, so I check white. It’s just that simple for me.”

The next scene opens onto a dark room, where a white-appearing man sits on a black bench. Throughout the film he remains unnamed, and so in this article I will refer to him as “the Patient”. He is hunched over. A nurse enters and asks him to fill out a medical form. When she leaves, he notices the question that asks him to check his race. He mutters to himself, “Every time I turn around there’s some form asking me about my race.” He calls for assistance and is answered by what sounds like a man’s voice. “Yes?” the voice says. The Patient answers, “Do I have to answer the race question? Why does the doctor need to know my race?”

“What’s so hard about checking white?”

What looks to be an older white man appears in the seat across from the Patient. He wears a white cotton shirt and white khakis. He claims that he is the ‘White Category,’ and wears an expectant expression as if the Patient should not only understand but also be familiar with his presence. What follows is an account of the history of the creation of racial categories. A history that spans hundreds of years and has landed in the Patient’s lap in the form of a question on a medical document.

The being that calls itself the ‘White Category’ says, “White, that little word, already had unshakable associations with purity, cleanliness, and unquestionable goodness. White, especially employed in the celebration of the passion of our lord…It has been made the symbol of divine power, sacred vesture, and spotlessness.”

Later in the film, trauma therapist La Shanda Sugg describes how associations with whiteness affected her psychologically as a Black girl growing up in Detroit. “I grew up being socialized to believe that success was anywhere that I wasn’t. I grew up in inner Detroit. If I wanted to see what success looked like, my father would drive me out to the suburbs of Detroit and he would present all these options of what I could have and what I could be and what I could do, but it was always connected and associated with whiteness.”

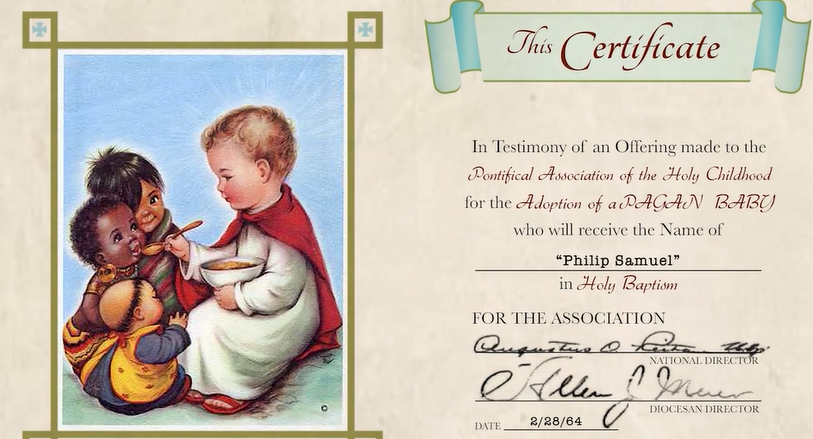

The Patient’s frustration with having to check the ‘white’ box is manifested in a resistance to the need for racial categories at all and the assumption that being labeled has not affected his perception of himself or others. The ‘White Category’ challenges this idea. He brings up the fact that, as a schoolchild, the Patient was encouraged by missionaries to raise money so that pagan babies in Africa may be baptized.

The Patient says, “I remember dreaming of going into a dangerous jungle to rescue my pagan baby.”

The ‘White Category’ chuckles and responds with, “Of course it was a jungle.”

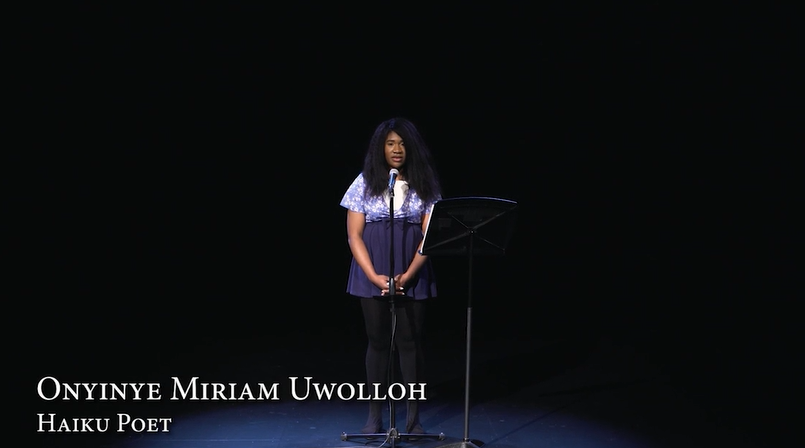

In the film, poet Onyinye Miriam Uwollo reads from her persona poem “The End Began When,” from the perspective of a young girl coming to terms with the colonization of her home.

“Brother said their god / must indeed be powerful / and went to their church / so brother grew proud / when they told him he was saved / and could step on snakes / he killed the sacred python / I overheard papa tell / ma we cannot fight it / we must be baptized / So I went to school / and learned that I was pagan / I was given the name Anne / since mine was heathen”

This persona poem pinpoints the lasting psychological effect that being labeled pagan has on a people. It is a poem that answers how these people were made to feel about themselves. The ‘White Category’ describes the narrative of the pagan child needing to be rescued by Jesus as a “marketing tool of the European takeover of the planet.” He speaks of a pattern of colonialism that is still present rather than an atrocity that was committed in the past. The Patient is at most in his 50s and was given a narrative that not only justified but also romanticized colonialism. This sprawling and disturbing history seems to be too much for the Patient to handle as he waves the ‘White Category’s’ words away and says, “I think we should just get rid of all the categories. They shouldn’t matter. I’m just gonna refuse to check ‘white’. In fact, I’ll check all the boxes. That’ll mess up the entire system.”

The ‘White Category’ responds, “Refusing to check race is not going to dismantle a system that took five hundred years to put in place. The racial categories are cemented into our thinking with or without checkboxes. Leave the wrestling to the categories. We, those of us in the white category, are the only ones for whom the past does not matter.” At this point, the Patient has lost patience with the conversation. He stands and paces across the room before turning his back to the ‘White Category.’

He says, “Why are you even telling me this?”

The nurse from earlier enters abruptly and the ‘White Category’ vanishes just as swiftly as he appeared. The nurse notices that the man hasn’t checked his racial category and assumes it’s a slip up.

“Hun, you forgot to check your race. I need every section filled out.”

“I was deciding whether to check a box or not.”

The nurse is baffled by his hesitancy to check the white category.

“Still deciding? What’s so hard about checking white?”

Coming away from this film, I had a question that was not dissimilar to the Patient’s: why is this man speaking to the ‘White Category’ at all? Throughout the film he is obviously distressed and irritated by the conversation and he walks away with a dissatisfying answer to his desire to “get rid of all the categories.” The first film in this duology, I’m White Like You, Right Mom?, has a clear motive for the character’s discussion with the ‘White Category.’ The main character is a white-classified woman who struggles to explain race to her Black-classified daughter. Her motive for talking to the ‘White Category’ comes from her desire to understand how to approach discussing race with her daughter, as she is worried that it will someday cause a divide between them. In Why White?, my initial thought was that the Patient may be talking to the ‘White Category’ in order to learn about the insidious history of race in the United States so that he could absolve himself of any guilt he possesses because of his privilege. But the ‘White Category’ just won’t let him off the hook. Anytime the Patient defends himself or tries to introduce a quick fix for racism, he is shut down. Not only is he reminded over and over of the long overarching effects of racial categories, but he is also told how the classifications allows the ‘White Category’ to uplift itself above other races, whether that be in the literal sense through classifying whiteness as inherently superior to other races or something more subtle, such as believing that a Black child must be rescued from their own home and culture and introduced to a European religion.

I also wondered if the ‘White Category’ was an entity that shared information with the knowledge that even undeniable facts and heart-wrenching stories would not motivate his inquisitors to look at themselves in a different way. However, I came away from both films interpreting the ‘White Category’ as a manifestation of anxiety and guilt rather than a real person, which means that the Patient initiated this dialogue with himself. When Black people describe our experiences with racism, this often encourages white people to step out of their perspective and listen rather than debate or investigate right away. This sometimes leaves me wondering if white people do talk about race outside of these conversations—with a therapist, with themselves, or amongst other white people. It is sometimes disheartening to think that Black people are expected to dismantle a system that we didn’t create while that very same system works against us.

This film as well as the Patient character in particular present us with an interesting reality, one where people are grappling with their relationship with whiteness, whether they like it or not. The films explore the conditions that the white identity is contingent upon, what narratives that shape the white identity to this day, and how those narratives affect relationships with people of other racial categories. The executive producer of these films, Joan Ferrante, is a white woman and has repeatedly spoken to the need for the white category to know itself, because up to this day the weight of responsibility has been placed on other racial categories.

La Shanda Sugg’s words close the film as she speaks to Joan Ferrante’s convictions:

“It’s an opportunity to have white-categorized people to come inside of their bodies so that they can begin to reconnect with this thing, this humanity that is necessary to solve some of the problems we have.”

Ariel Yisrael is an Ohio-based freelance writer and poet with a mission to report the therapeutic value of the arts specifically for underrepresented members of a community. A recent graduate of Northern Kentucky University, she uses her experience in creative writing to explore topics of physical and mental health and wellness.