Featured image: A film still from The Categories Black and White. Actor Caleb Farley plays Archy, and actor Landon Horton plays Thomas. A man who appears Black stands facing away from the viewer, while a man who appears white stands to our left and faces towards the viewer. Image courtesy of Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project.

Mourning Racial Categories is a four-part series discussing four films that have been created as part of the Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project. This project engages the visual and performing arts to tell the stories of how people in the United States were divided into a handful of unequally valued racial categories, such as Asian, Black, and White. MCRC offers a language for the trauma suffered by our country, communities, and relationships caused by the formation of these categories.

“I stood watching him as he walked rapidly away. And as I stood looking I wanted to sink into the Earth in shame and mortification…It was a base desertion, not even a love of liberty could excuse.” – Archy Moore

The Categories Black and White, available for viewing at KET.org, is a film that hopes to offer a language through which the creation of unequal racial groups in the United States may be both mourned and understood. The film was created as part of the Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories project (MCRC), which uses the creative and performing arts to reveal the United States’ history of division on the basis of race. They reveal this history with the hope that this exposure might encourage viewers to both acknowledge and heal the wounds that these classifications have left. The film features interviews with MCRC members, each a contributor in the film’s development, in ways that vary from poetry, dance, theatrical performance, and more. As part of their contribution to the film, participants were asked to read and watch media that dealt with relationships that were damaged by unyielding racial classifications. Participants also learned of the specific laws and practices that were employed to create division between different races. Each member describes the way that this knowledge altered their perception of race and the race narrative. Through the lens of these participants, the audience learns as well.

In the film, Joan Ferrante, Professor of Sociology and founder of MCRC, describes how her experience writing a book about racial categories influenced her decision to start the project. “I woke up one morning thinking, I’m gonna issue a call for participation [in the film] to students in the Creative and Performing Arts [department at Northern Kentucky University] and ask them to come together with me in a three week workshop where we would think about ways to mourn the creation of racial categories. I was writing a book on how racial categories were created in the U.S. and sustained over 400 plus years. It was clear to me that this was something to be mourned. What would this mourning look like?” She realized that academic environments like the classroom were not sufficient enough to encapsulate the present emotional and psychological effects of race, so she and a group of creatives developed the film The Categories Black and White.

The film opens on two dancers dressed all in black. The dancers appear to be of two racial categories, though such an observation is made more complex throughout the film. The two dancers embrace. Then, one dancer, who appears Black, has what looks like a white cotton rope wrapped around their wrists. The other, who appears White, backs away from the other hesitantly. He walks to the edge of the stage and looks back for a moment before leaving. The other dancer, who is left on the stage alone, chases after their companion for a brief instant—then stops. With a white rope stark against her wrists, she falls to the floor, head heavy with the weight of her abandonment. She curls into a ball on the floor. A child in the womb.

The heart of the film is the performance based on the novel, The White Slave, published in 1852 by Richard Hildreth, an American journalist, author, and historian. The story involves two enslaved men: Archy and Thomas. Thomas appears Black. His friend Archy, the son of an enslaved woman who appeared almost white and who is a slave master, appears white.

During a conversation with project founder Joan Ferrante, she explains laws and conditions that made it so that white-appearing people could be enslaved:

“Archy follows his mother’s condition as enslaved. Archy’s biological father is also his owner. It does not matter that he appears white or who his father is, he follows his mother’s condition. It is her African ancestry (which is almost imperceptible in her appearance) that deems him enslaved. The condition of the mother ensured intergenerational enslavement unless the child appeared white enough to pass. Passing required that Archy break all ties with mother and friend Thomas and even his father. That is the only way he can disappear into the White category. He must erase his past and never utter a word about his origins.”

Two actors perform the scene from the novel wherein Archy and Thomas are forced to separate so that Archy might pass into the racial category and be free. The pain from these individuals seeps into the actors themselves as Archy and Thomas rush through the woods and river, away from each other.

“The separation of Black and White is made in the decision [to go different ways],” says Kirsten Hurst, a regular poetic contributor to MCRC, “in response to Archy’s decision.”

The story of white indentured servants and white-appearing slaves does not delegitimize the unique violence committed against Black appearing enslaved peoples. Instead, it shows the psychology of the American; the rules that we use to place people in single racial categories often defy logic, while at the same time hurting those who are forced to pick just one.

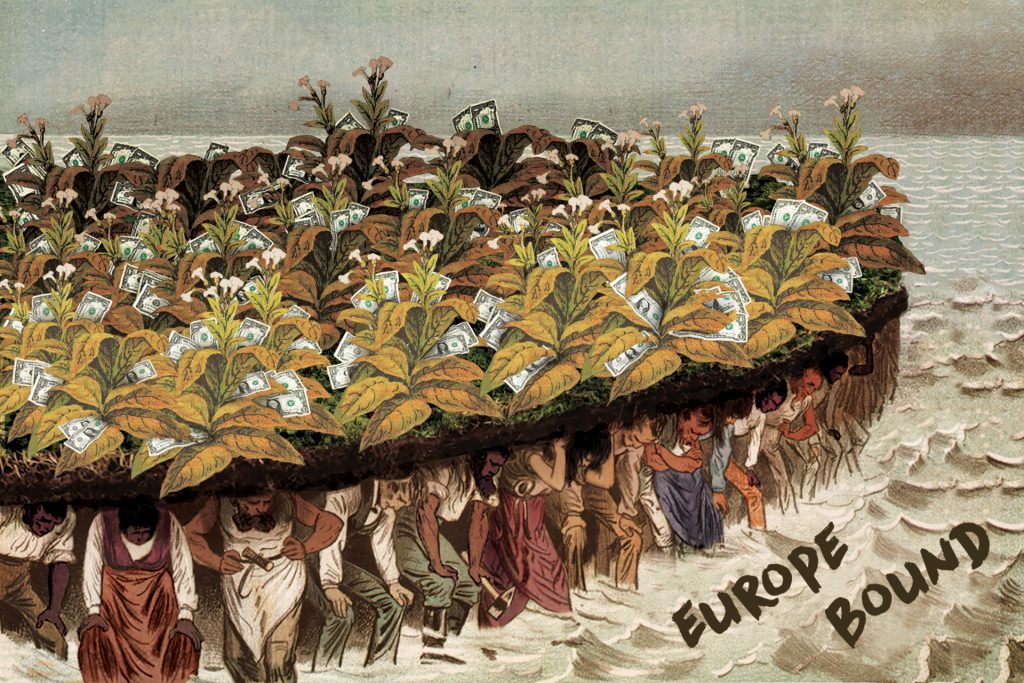

The film highlights the past of these classifications as well as their psychological present. It describes the first English settlement in Jamestown and how the servant population of that time looked so different than what we envision today. One image, created by digital artist Carly Strommaier, is particularly arresting. It is an illustration of muted tones, which shows men and women with a variety of skin tones and racial classifications bent over, some with their arms crossed and some with hands pressed to their knees to keep from falling over in exhaustion. They stand up to their knees in rushing water. Its heavy waves can be heard swirling around them in the film. These men and women are holding up a large circle plot of land. Growing from the land are tobacco leaves and bills of cash as if they were one and the same, Europe bound.

In this settlement, English and other Europeans, Africans, and Indigenous people worked together in the tobacco fields. Workers united to rebel against the planter and political elite in the hopes of improving their living conditions. In order to quell the unification of these separate groups these elite groups created systems specifically designed to separate the groups.

These laws affected the psychology of the people. They encouraged white indentured servants to embrace the idea that there was a difference between themselves and their Black counterparts, whether they worked side by side or not. Black classified people that could pass for white were incentivized to leave family behind so that they might pass into the White category. This is the weight of race.

In The Categories Black and White, participants were asked to read two novels, one being Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs and the other being God Help the Child by Toni Morrison. One such participant is India Hackle, a contributing poet and one of the founding members of MCRC.

During our conversation, I ask India, “How did reading [Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl] affect your perception of race?”

She responds, “With Incidents [in the Life of a Slave Girl], [it was] less about race and more so about the authority that Harriet Jacobs took on. I just never heard those stories, especially from the person themselves. I’ve never seen a woman who was a slave take back her power in whatever way she could, even if that was occupying her womb. That’s what altered me the most I would say, because I feel like those were the stories that were hidden from me. I think that was what started my drive more than anything at MCRC.”

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is an autobiography detailing Harriet Jacobs’ life as an enslaved woman who was relentlessly harassed and abused by her master Dr. Flint. In spite of Flint’s obsessive attempts to control her, Jacobs has children with a man that she has actual affection for.

In God Help the Child, a light skinned woman gives birth to a dark-skinned child that she struggles to connect with due to the difference in their skin tone. In her mind, there is an inherent difference between her and that child. This is the “unnerving burden of race,” as India Hackle says before she reads an excerpt from her poetry series, I Love You with All My Weight. The poem describes a relationship between a white appearing father and his dark skinned child:

“I love you with all the hairs on my head… / He’d exclaim his love to me but his confusion to my mother / If Virginia is mine how is it that she doesn’t have not one trace of me in her / not my blue eyes / not my pale skin / nothing / who you been sleeping around on me with woman / he’d joke… / One night he came to my bedroom hours after my bedtime with liquor seeping through his pores / he told me to come have milk and cookies. / Minutes later there I sat with my bottom on the kitchen table / my legs swinging in a sugar high / Those black knees don’t belong on my baby girl / and he began wiping the black off my knees in circular overdramatic motions that tickled / I laughed.”

These strict racial classifications, often determined by appearance, affect the way that we interact with our children and our ancestors. Kirsten Hurst, a white appearing individual, states that “you don’t see my non-white ancestors imprinted on my face or my skin really at all.” Her poetry describes the “loss and separation that has occurred between ancestors toward that journey to the creation of me.”

Madison Pullis, writer, dancer and one of the founding members of MCRC, describes a moment when the present day weight of race became clear to her. A black child recently adopted by her mother is given a Black baby doll for Christmas. The girl rejects the gift and cries that the doll is Black and therefore ugly. “She’s four, I don’t know how a four year old could possibly have gotten that. It has to be in the way we talk to, in the way we treat, in the way we touch our children.”

“There has been 400 years of piling up emotions and shame and hatred and terrible human treatment,” says Carly Strommaier, the artist behind several digital collage art pieces in the film. “By pulling these images, I’d like to tell the story of these severed human relationships and the things that we inadvertently pass down to our children.”

Ariel Yisrael is an Ohio-based freelance writer and poet with a mission to report the therapeutic value of the arts specifically for underrepresented members of a community. A recent graduate of Northern Kentucky University, she uses her experience in creative writing to explore topics of physical and mental health and wellness.