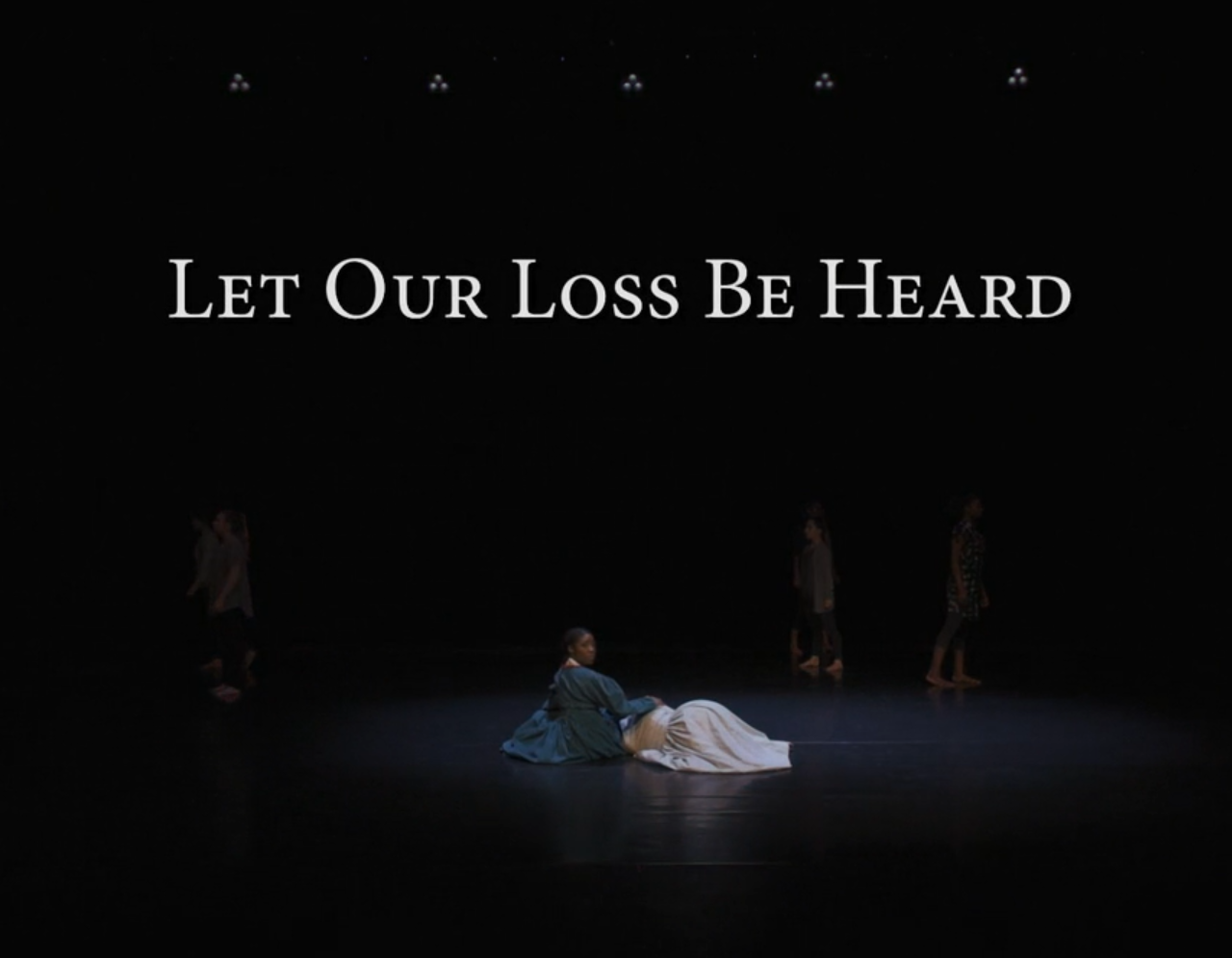

Featured image: A film still from Let Our Loss Be Heard. Lavette Patterson plays Margaret Garner and Hannah Duvall plays Mary Garner. Margaret Garner sits in a blue dress while looking towards the audience with her hand on her daughter, Mary. Mary wears a white dress and lays down on the stage. The background is completely dark. Courtesy of Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project.

Content Warning: racialized violence and sensitive language.

Mourning Racial Categories is a four-part series discussing four films that have been created as part of the Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project. This project engages the visual and performing arts to tell the stories of how people in the United States were divided into a handful of unequally valued racial categories, such as Asian, Black, and White. MCRC offers a language for the trauma suffered by our country, communities, and relationships caused by the formation of these categories.

The Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project (MCRC) was started by Joan Ferrante, professor of sociology at Northern Kentucky University. While teaching classes on race, Joan found that her students had a difficult time engaging in meaningful conversations about race even though they bore the weight of the classifications themselves. Academia alone did not offer students the language to unpack their relationship with their racial classifications, so she put together a team of students and faculty in the creative and performing arts to collaborate and create projects that would engage people with race.

I officially became a part of MCRC in late 2020, having previously been in the room during roundtable critiques of the films in their development stages. I’ve been able to see the film Let Our Loss Be Heard as a collection of images, poems, and artworks individually before they were put together for the film. To watch its premier as a full-length feature in January of 2021 was a truly gratifying experience made all the more so because I knew how far it had come.

Through a contemporary dance performance, Let Our Loss Be Heard tells the story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved Black woman who, in 1856, crossed the Ohio river into Cincinnati in the hopes of finding freedom in Canada. Instead, she and her family were caught and in those moments before being taken back into captivity, Margaret Garner decided to take the life of one of her children and attempted to take the life of the other three. According to newspaper reports, two of her children appeared “almost white.” Clips of the arresting dance performance are interspersed with images of artworks, poetry readings, interviews with multiracial families, and a conversation between sociologists La Shanda Sugg and Belle Zembrodt. This combination of imagery and audio comes together to tell the story of race in America; its past and its psychological present.

The film opens with an interview. A woman stands smiling at the camera:

“My husband, category White. We had a child together, our first child, and we went over the normal birth plan…but it was when the birth certificate came into the room when I was at awe at what am I going to do, what category am I going to check? Being a Biracial woman and my husband being White, things are going in my head. I’m doing fractions. I’m half Black, he’s full White–that’s a quarter Black. What do I do? And I checked category White because I felt that…my child, when seen in public, would only look White. The trauma of that for me as a Biracial woman was that I gave up my category that day and it was very emotional. And I could not describe that, not even to my husband…until you presented [the Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project].”

The liminal space of those who do not fit into one racial category is apparent. Not every form that asks for your race allows you to check more than one box. This compulsion to assign individuals to these few strict racial classifications leaves us with no language to process the complexities of those classifications. The Garner story personifies our thinking about race today.

I spoke with MCRC project founder Joan Ferrante and writer, poet, and consultant India Sada about their relationship with the film.

India Sada: What stood out to me when showing the Margaret Garner film, [is that] usually audiences respond [by] still trying to understand what was Margaret’s psychological break. A lot of White-identifying people still can’t connect themselves to Margaret Garner even though she had White appearing children. Even if we follow the storyline of like, oh, [Margaret] could have passed [as White] and things like that, for some reason, they cannot connect themselves to Garner. That was always surprising.

Ariel Yisrael: What does that mean? What have they said to you that makes you feel like they can’t connect with her as related to them?

IS: They’ll just focus on the horror of what was done. They’ll focus on Margaret saying, “I’d rather kill my children myself than return to slavery.” They’ll focus on the horrors of slavery. And then it’s the horrors of Margaret killing her children. They’re shocked like, (gasps) “Oh my God, this was so bad.” So it’s hard to stop them from saying [things] in the past tense. Yes, this was one event that happened past tense, but you got to drag them to get the lasting effects. They rarely get the lasting effects.

AY: Yeah, that makes sense, especially the shock. Being almost eager to be shocked and appalled instead of…

IS: Yep. Eager to be sad. I will sometimes sit in the back [during showings of the film] and, without fail, usually the White-appearing [audience would be shocked and sad] when we’d have that scene where she kills her child. I can’t speak for the entire room of people, but usually just based on observation, I do not get that [reaction] with the Black-appearing [audience]. It’s not like this is something unexpected–we didn’t put it in there for that reason. We didn’t put it in there for shock value, so why are you shocked?

When India says this, I can’t help but recall my experience researching Margaret Garner for this very article. When searching her name alone, I was hard pressed to find a headline that didn’t feature the fact that she killed and attempted to kill her children. This was the case for the New York Times and the National Public Radio. And whether or not the articles mentioned her bravery or the complexities of her children’s racial classifications, what was most pertinent shined in the headline: the horror. On the heels of the Black Lives Matter movement, there is perhaps an eagerness to not only remember the horrors that Black-appearing people have suffered, but to also express that horror to Black-appearing people today.

So rather than watching a performance of the past, Let Our Loss Be Heard implores us to question how we interact with race in similar ways even in the present. Margaret and her family have historically been portrayed as entirely Black appearing. Even the mural in Covington, Kentucky that is meant to commemorate Margaret’s bravery portrays the family as entirely Black appearing. Mary, who was a White-appearing child of Margaret, exists for the first time because of this film.

and actor Marcellus Howie as Robert Garner reach out to embrace one another. They are playing characters that are father and daughter. The background is completely dark. Courtesy of Mourning the Creation of Racial Categories Project.

AY: What do you think about the idea that every original story has already been told? It’s all been done before. And we have seen it all. Do your films challenge that idea?

Joan Ferrante: I think the [original stories have] been suppressed. They’ve been told incorrectly and I don’t know that we’re doing them correctly. You do the best you can. These are not common stories for our nation; for the Black community, they are. The way we are looking at these stories [in MCRC] is not normal. The lens of history affects how you see the story. What MCRC is doing is what our country is trying to do. We’re in 2021 and we’re trying to wrestle with race in the lens of today and that’s what makes it new.

The influence of the present perspective is apparent in the film’s music. Vocalist, Ariyana Hardy, sings the negro spiritual, “Walk Together Children,” alone in the film, rather than with a full choir, which is the tradition.

IS: We [instructed vocalist] Ariyana to sing [for the song Walk Together Children], and [professor in the Theatre and Dance Program at Northern Kentucky University and a longtime contributor to the project] Daryl Harris told Joan, “Don’t give [Ariyana] any directions on how to sing this,” because it was a negro spiritual. “You can’t give her directions, you’ve given her the music, let her come in and just figure out how she wants to do it.” So when she came in with no direction on how to sing it it was…way slower… just more felt. So we ended up having to rearrange where that piece was going to be placed because it sounded more like an ending piece the way she sung it specifically. It’s just small stuff like that that was very unexpected but ended up working–those magic moments.

What I think happens sometimes with films is that you’re coming in with your own ideas and then some information is coming through, but it [takes] so much to really question what you’re thinking in that space. I honestly don’t think it’s the film [that really breaks through], but more so the conversations and questions after the film, where people are asking something because they think, like, “Oh, I got it.” So I think the most effective [context for this film] would probably be classrooms and would probably [include] something like tasking people to do, say, or write something after the film. Because whatever you picked up on now you gotta bring to the table.

Video: Trailer for Let Our Loss Be Heard.

Ariel Yisrael is an Ohio-based freelance writer and poet with a mission to report the therapeutic value of the arts specifically for underrepresented members of a community. A recent graduate of Northern Kentucky University, she uses her experience in creative writing to explore topics of physical and mental health and wellness.