As part of Chicago’s Envisioning Justice project to address community concerns around criminal justice through arts education, Open Center for the Arts in Little Village worked with teaching artists to bring specialized courses focused on immigration, incarceration, and political organizing to their students. Filmmaker and media instructor Jesús Mario Contreras was one such educator, teaching a series of filmmaking classes to youth and young adults from the neighborhood. He shared with me about his particular teaching philosophies of art as cultural communication, youth allyship, and the importance of self-reflection.

Anjali Misra: How did you become involved with Open Center?

Mario Contreras: Pepe Vargas from The Chicago Latino Film Festival recommended a friend of mine for the job of instructor. Arlen Parsa, director of The Way to Andina, thought I’d enjoy the opportunity.

AM: Can you describe your work with Open Center? What was day-to-day teaching like, and what were some highlights (best personal moments with students, staff, community members, etc.)?

MC: I was one of many instructors that Open Center students worked with over the summer. Each week, they’d spend time working on comics, theater and video. Our co-teachers, Aaron and Jose, also brought photography and acting expertise to each of our classes. They served as guides through the three classes and created links between the lessons they were learning on other days of the week.

One of my favorite days was when we wrote and shot a music video. The students opened up about their lives and found a way to put their thoughts into scenes that we could shoot. Once they got started, the ideas kept building on each other and inspiring more ideas. The video they made was messy, but we were all very proud to show it to the community and the students enjoyed inside jokes about the production every time they watched it.

AM: Why is art important in Little Village?

MC: Art is important everywhere! As an entry point for immigrants in the Midwest, Little Village uses Art to connect newcomers to the community and help them find their way in a new environment. Also, as the children of those families grow older, they use Art to establish their own communities, languages and cultures.

AM: How do you see your work contributing to “envisioning justice”? What does justice in Little Village look like to you?

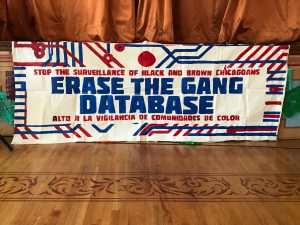

MC: My goal for Envisioning Justice was to provide a growth experience for young people to voice their concerns about surveillance and incarceration. It was important for me to listen to their day-to-day concerns instead of imposing my feelings about justice on them because I don’t live in their community and I’m nearly twice their age.

Coming to agreements about how to treat one another and communicating in a unified voice that represented everyone that wanted to be heard felt just to me. Especially as we used the tools of mass surveillance to free ourselves from the cages we’d created in our minds.

Talking about all the ways we’re watched and tracked can be daunting. It was important for us to turn the fear of surveillance into something they could live with. We discussed local surveillance that we provide each other as neighbors and family.

They agreed that group texts are a great tool for informing one another about areas to avoid or alerting friends that they’re on the move, so they can be tracked through apps. That helped me understand how GPS tracking and data mining that many fear as intrusive helps young people keep each other safe.

As a film class, our relationship to surveillance is complex because of our participation in it. We spent time shooting portraits of one another and shooting ‘creeper’ shots without the subject noticing (they all consented to the game ahead of time.) The exercise gave us the opportunity to discern whether subjects of a photo were willing participants or not based on visual clues and aesthetic choices.

It also opened a conversation about how the awareness of being watched changes our behavior. This was how we related the ideas of surveillance and mental incarceration, by talking about how the thought of being seen can influence how we dress, talk, walk or act.

The lack of control over how we’re all perceived provided an opportunity to empower them to take control of their stories. By writing, shooting and editing their own films, they expressed many of the complexities of living under mass surveillance from a perspective of their own.

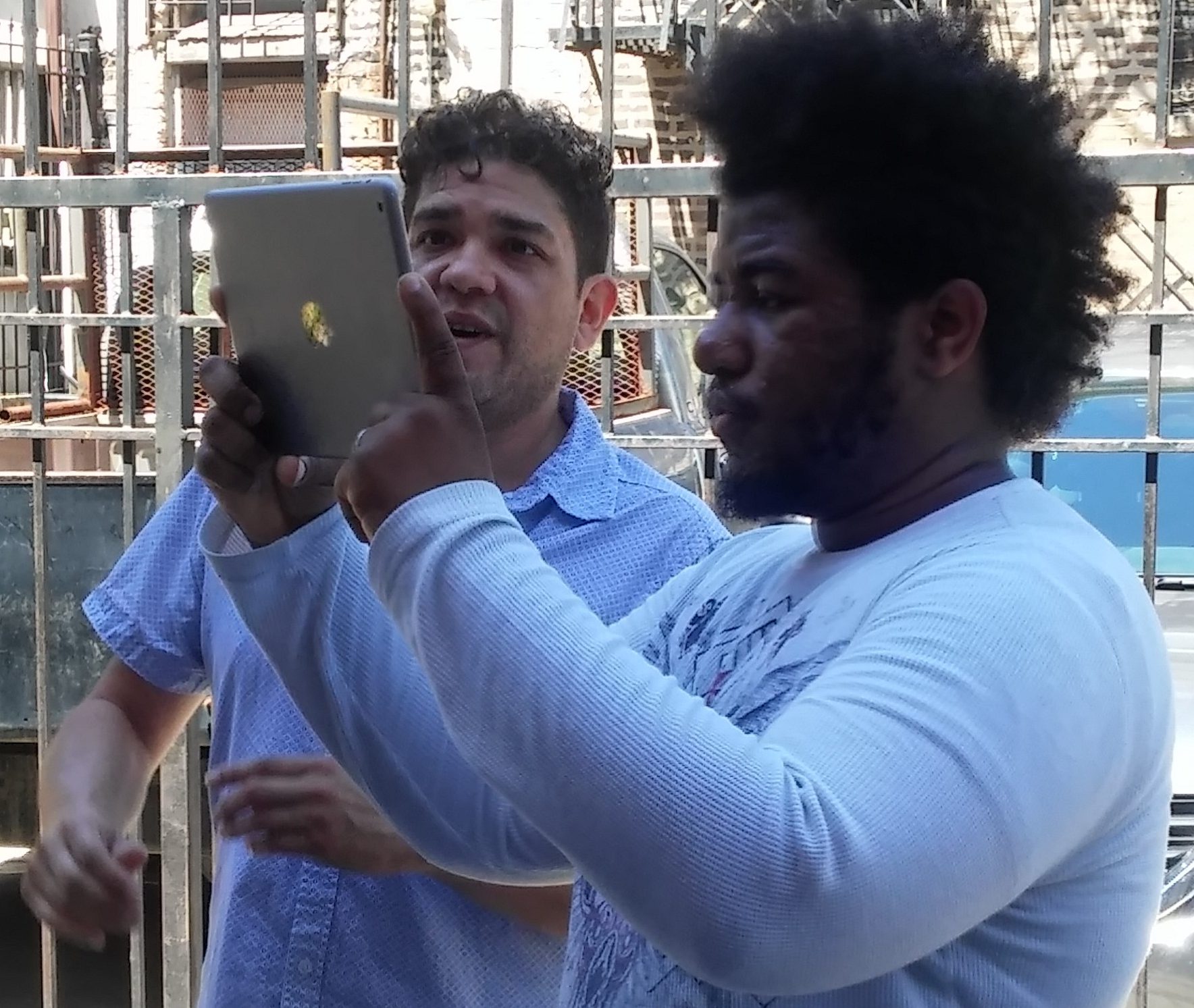

Featured image: Photo of film instructor Mario Contreras helping a student record outside. The student holds an iPad up in front of him. Photo courtesy of Arnie Aprill.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.