MASHA: It’s about time for the performance to start.

MEDVEDENKO: Yeah… Konstantin wrote a play.

After March 2020, the first play I saw live in the theater was Seagull at Steppenwolf Theater, on its closing weekend this past June. As many of the reviews pointed out, the play served as a vehicle for the grand opening of the company’s new, in-the-round theater, built and opened during the pandemic. Even though the show was not the first to be open with full capacity to the public, having it at the new space, and with a cast “stacked with Steppenwolf ensemble,” the show really felt like the company’s return to live theater.

In truth, I had seen a few other shows since, and during, the pandemic. Different theaters of course had experimented with different modes of COVID-safety protocols. But seeing Seagull, ensemble member Yasen Peyankov’s adaptation of Chekhov’s primer for all of modern Western theatre, felt like the litmus test. As I sat in the theater waiting for the play to start, I asked myself, is it ok to do this? Is live theater back? Did it make it out alive?

The play didn’t answer those questions for me, of course. It would have been nice to get a clear-cut answer, but that is not the play’s job. Instead, I left with the familiar sensation of liking parts, disliking others, and genuinely wondering if I should ever go back again.

Chris Jones noted in his review that it had a “workshop feel.” I didn’t agree with all, or even a lot, of his review, but I thought that was accurate; that workshop-feeling made me like it more than I otherwise would have. It made the room feel full with possibility, which is not always my experience at more polished theaters like Steppenwolf. I liked how the actors were negotiating their tempos around the actor playing Konstantin, who was understudying the night I saw it.

That was a few months ago, in the summer. Upon writing this essay, it was announced a few days ago that “The Phantom of the Opera” on Broadway will close its doors for good. It was the longest running Broadway play, and ticket sales after the pandemic weren’t enough to sustain the streak.

I can’t say that I am upset about this. But, it is sad. It is not a good outlook for live theater, which is the main thing I do with my life – this thing that I sometimes like, often dislike, and am rarely surprised by anymore.

A moment that keeps ringing in my memory from Seagull: the sound of an exceptionally half-hearted attempt at a prop, a dead seagull, landing with a plasticine thunk within the perfect acoustics of the new theater. The effect was ludicrous, taking me out of the play instantly, while the actors sat in it like a bed they didn’t want to sleep in. Maybe it was supposed to be a kind of self-aware joke, but for me, it didn’t land.

What are they doing? I sighed. The moment made me so angry. At the same time, it made me so happy. Here it is. Here is the place where mistakes are made.

KONSTANTIN: The curtain goes up, the lights come on, you’re in a room with three walls, and there they are, these servants of art, and all they do is show us how people eat, drink, make love, walk, and wear clothes!

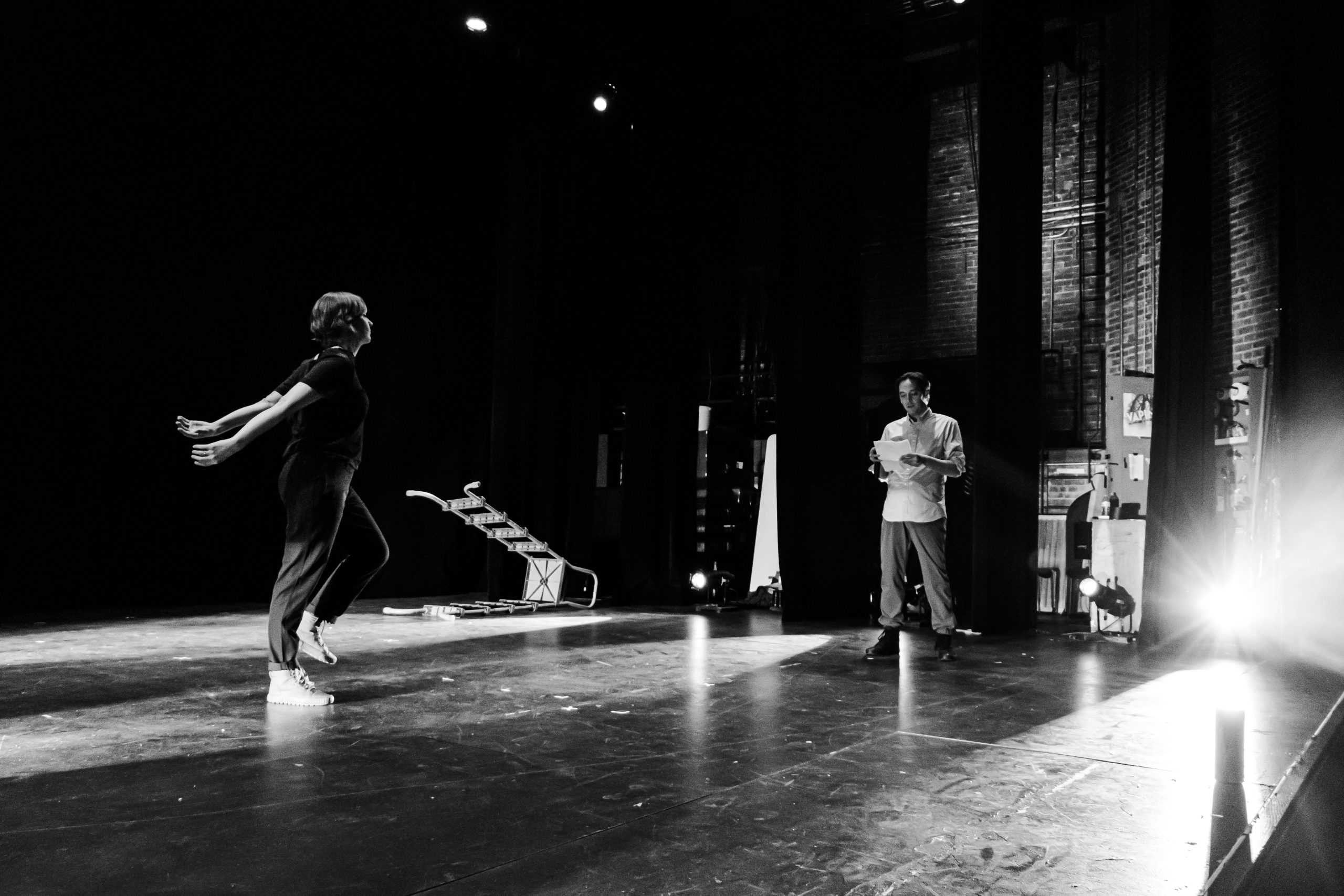

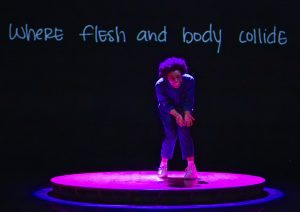

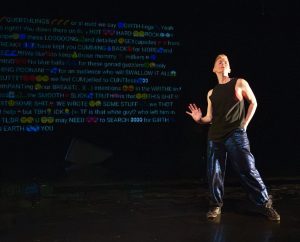

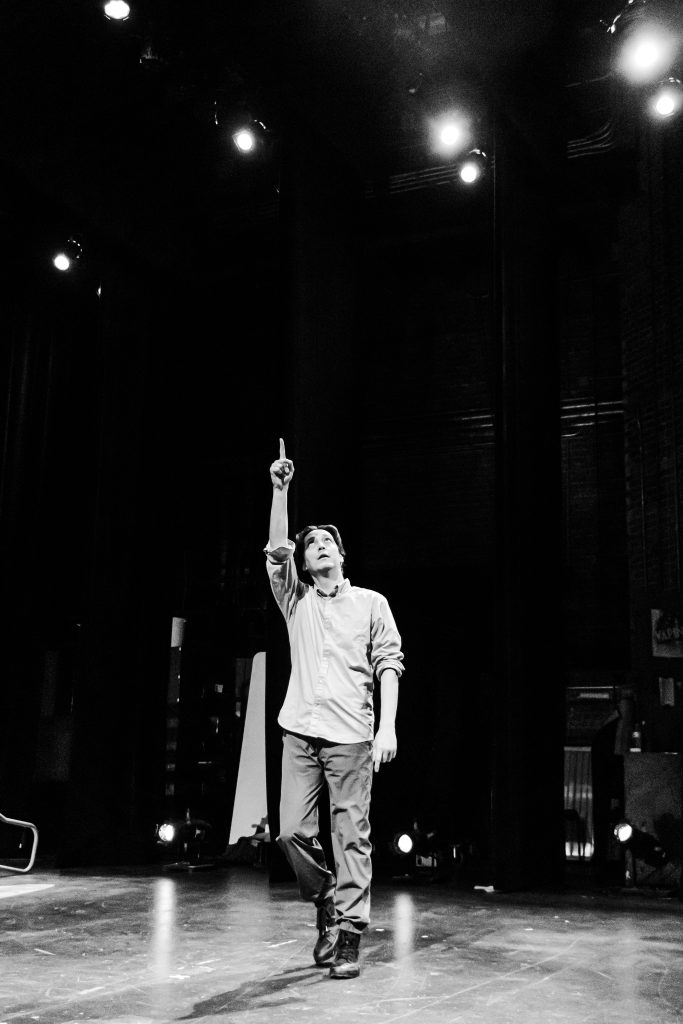

For a week of the summer at an artist retreat, I was developing a two-person show with dancer and choreographer, Melinda Jean Myers. The show is called “Unfinished Business,” and we showcased it for a small group of colleagues with Lucky Plush Productions (LPP), a Chicago company under the direction of Julia Rhoads. Mindy is a company member with LPP, and the company is presenting the show this fall at Links Hall. So this was a good time to get some valuable insight from some smart and tactful people, before we brought the show to the public that may or may not be ready to show up to a theater just yet.

After the showing, we all sat down to receive feedback and discuss the work as a group: what was working, what could be improved upon, or expanded, etc. The discussion ended up being one of the best I’ve been a part of, and it made it that much more special for it being toward a show I was working on directly.

One moment really has stuck in my mind though.

The moment came when Leslie Buxbaum Danzig, co-director of many of Lucky Plush’s works and someone whose work I have been a fan of since I moved here in 2005, looked at her sheet to give me a sincere note: grinning, she said, “One of the first things I have on my paper here just says, ‘Kurt can actually act.’” The whole group laughed.

I laughed too, because I understood Leslie’s comment. She wasn’t surprised, necessarily, at my ability to act. It’s just that she had never seen me onstage acting. Because usually when she had seen me onstage, it was at The Neo-Futurist Theater, and with that company everybody was being themself, including me. The way she put it: “I usually see you in a context where everyone in the audience knows what the game is.”

I liked that thought: all this time, I wasn’t performing theater. I wasn’t acting. It was more like I was playing a game.

In “Unfinished Business,” I don’t act much at all. Mindy doesn’t either. Most of the time, we are being ourselves, speaking our own words, telling our own stories. The moment when I do “act,” I portray Nina, from Chekhov’s The Seagull, delivering her final, tragic monologue. It’s a part I never thought I’d play, especially after having not acted in a little over a decade.

Being that out of practice, it was sort of foolish to do that to myself, to cast myself like that. Which is probably exactly why I wanted to try it.

SORIN: But we need theater! Can’t live without it!

I am 40 years old. A while ago, a couple years shy of half my life, I got a Bachelor of Arts from the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Maryland-College Park, majoring in Theatre with an emphasis on Acting. This was never my intention, however. When I graduated high school, my goal was to pursue a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, a distinction commonly understood by the higher amount of specialized, intensive art and practice classes the person takes in the BFA track. Another distinction is that, typically, you have to audition and be accepted into the program.

I attempted this, multiple times for multiple programs, and I failed at all of them. The chances of getting in can be slim, and I didn’t really know what I was doing, or I wasn’t ready to say the right things at the right time to get the part.

I recall one audition for SUNY-Purchase, where the auditor stopped me in the middle of my monologue to ask me, “What is it your character wants?” I didn’t have an answer ready, and they let me start again — before stopping me a second time. I knew I was done for. All these auditions I was going for were moot at this point. I didn’t know how to act, and I wasn’t going to learn how; at least not in the intensive, concentrated way that I thought I wanted. Instead, I would go on to get a liberal arts education, take a number of acting and voice classes, participate in a few “main-stage” plays, before eventually focusing on writing and creating my own pieces that threw me into the realm of writer, writer-performer, performance artist, or theater-maker.

Yet here I am, acting anyway.

And in 2022, things are ‘picking back up again,’ and the desperation in the promotional copy is palpable. I’m navigating the ‘new normal,’ swimming in a world of “returning,” “reemerging,” and “resetting. Every organization is perpetually “re-imagining” as myself and other like-minded artists walk over eggshells, skeptical that this art will prove vital in the current culture where physical proximity has proved to be not only deadly but generally inconvenient, everyone quickly losing the habit and maybe even the natural impulse, if there ever was one, to gather together and watch people like me try to make something happen — an attempt at something seeming so “alive,” it’s almost as if I (acting, in this case) have no prior awareness of the words that are coming out of my mouth, as if I am just stirring up all these thoughts and feelings, right here in the moment.

Which of course, is a lie.

KONSTANTIN: We have to show life not the way it is, or the way it should be, but the way it is in dreams!

NINA: I think a play ought to have a love story.

But yes, to Leslie’s note, I can act. It’s just that I have been spending most of my time and energy, wondering why I would ever want to.

In acting classes, I was taught to understand these three things about my character: what they want, what they need, and what they must have.

KURT: If I may say something, I have an idea that you might like. It’s an idea for a play. A play or a story, really, it doesn’t matter. It’s all the same. If you like it, you can have it. It has a title, and the title is, “The Boy Who Wanted Nothing.” It goes like this:

There was a boy who wanted nothing. So his mother took him to a dance. She said, “Is this something you want?” And the boy just looked at the floor, while all the dancers danced and danced….

I was taught to identify these wants, needs, and must-haves throughout the script, in minute detail. For example, if I had the line, “Get ready. It’s time for the performance to start,” I would identify that I want everyone to give me their attention under the line “Get ready.” For the following line, I would note that I need everyone to be on time to the performance.

For every line, sentence, phrase, word, or utterance, I would name an intention. I would be instructed to write out long transcriptions of those intentions, using the want, need, must have language, and I would turn those in for a grade. In theory, I could do this treatment over the entire track of a character in a play, creating an internal dialogue of subtext, under the actual words I would say in performance.

KURT: Then the boy’s mother took him to a pool, with a big tall diving board. And off the diving board, other boys and girls would jump off, flip in the air, and dive into the water, straight as can be. The mother asked the boy, “What about this? Do you want this?” And the boy just looked at the ground, while the water splashed on his sneakers.

I would complete that script notation for a grade, but I never really did it in practice. It took too long, and there were other things demanding time and attention, like memorizing the lines. Those sentences I crammed into a script never really felt like the thing, never exactly what it should be. Anything I would call my subtext or my intention — as a character but also as myself — what I wanted, what I felt, would come in a more abstract form, lacking subject or material. I felt it dancing like a fire, but firmly on course. It was full of breath. If I had to put it to words, it’d look more like this:

want, want, wa-, i want, i, must, i, need, nee-, i need to, i, i need i ju-, just, i just, i must, i, how can i, over here, here, i need, i need it h-, here, it, i need it, here, i want, i want, i want th-, them, them here, i want them here, i need, come on, i, come, come on, come-

And I wasn’t going to begin to write that down. Where would that go? How could I share that?

KURT: Then the boy’s mother took him to a theater. And at the theater, there was a play. It was a weird play, kind of a bad play, but interesting. The boy got a feeling from it. One of the characters in the play particularly interested the boy. He was a sad character, kind of mean, he wasn’t nice to himself, and he hung his head in shame, just like the boy would when he didn’t know something. Plus, the character’s name had a similar sound to the boy’s name, and for some reason that mattered to him.

The mother looked at the boy. And the boy told her, “I want that.”

For a while, this was my practice, and this was the art I made: I’d be assigned a character, I would be given a script, and I would make sense of that script and character. I did some version of the things I learned in college, and I would repeat that, over and over, until I was ready to do it in front of an audience. Except of course, the audience wasn’t supposed to see that stuff from rehearsal. There, we unlocked and discovered all the moments for the first time, in frustrating and joyful ways. We would witness each other’s weirdest, strong-but-wrong choices. To me, that stuff was much more alive.

KURT: So he acted. And he acted and he acted. But the characters he played were all the same. Like a child with an animal friend. Or another child, but with confused eyes, always asking “What?” all the time. Or just someone or something without a name.

So, the audience wouldn’t see the other thing, the interesting thing, where we would repeat and repeat and repeat. Instead, they would hear the words from the play, they would see the steps that were set, they would see the doors open when they should and the actors pass through them when no one was in the way. Maybe a light would change from white to blue. Maybe the whistle of a train would sound. And that was that. And I didn’t want that.

KURT: So the boy stopped acting. He did other things instead, like work and eat. But sometimes he went to the theater. He would watch everything happen, and he would watch everyone do what they were supposed to do. After it was over, he would look down at the floor and head home. Or something.

KONSTANTIN: That’s an interesting story, Uncle. Now here, take this vaccine. We shouldn’t wait much longer.

During my time as a Neo-Futurist — that’s the theater company where everybody is being themselves — in the plays I wrote and performed, as well as plays written by my peers, I discouraged the presence of anything that could be remotely associated with acting, including but not limited to: playing characters, being in character, character studies, character arcs, objectives, super-objectives, script copies, sides, line notes, line readings, table readings, music stands, certain kinds of props; set pieces that a character could sit on, lean against, open, shut, or walk through — or anything to do with the voice, the body, warming up the voice or the body, wearing costumes, putting on make-up, donning masks, accents, impressions, having any association with stage business, sotto voce, silent upstage chorus banter, miming; and even in some instances singing, dancing, and entertainment in general. And, of course, subtext.

(Clowns were ok. It’s not that clowning didn’t really feel like acting — it did, like the horniest version of it — but the people who were clowns didn’t even think clowning was clown so at some point it felt like a non-issue to all parties, and so it was more about just making sure no one put on an awkward costume.)

As a Neo-Futurist, my theory, was that, by eschewing acting, I could effectively neutralize all those x-factors that could possibly, and often do, make theater one of the most unreliable, unbearable, cringey ways to spend an evening on a weekend, let alone an Industry Night on a Monday, when you could be at home, catching up on TV, or applying for law school.

It didn’t work, though. Acting kept creeping up.

NINA: Konstantin, do you remember how happy we were? How bright, how warm, how full of joy our life once was? The feelings we had, like beautiful flowers. Remember? I know it by heart.

For as much as I rejected it, and didn’t want to do it, and sought to replace it with something else, the work I made as a Neo-Futurist kept gliding alongside my latent acting practice, and stuff would keep creeping up. Many of my plays, I found, were deliberate explorations of the gray area between the moment of acting and the moment of being yourself.

One example was a two-minute play I wrote, titled “Playing Catch With An Actor.” In the play, I asked for an audience volunteer with experience as an actor, and I would ask them to play catch with me. I would then ask them about their history with acting, when they did it, their experience with it, what they loved about it. The conversation was usually easy and casual, but the emphasis was on the task of playing catch itself. If the actor stopped throwing the ball, I would insist that they keep playing, interrupting their thought so I could tell them to keep throwing the ball. The audience would learn a little about the person, where they came from and what they thought about their art and their career, but any moments of laughter, levity, or even conflict, would come from playing the game — especially if they were unpracticed, kind of nervous, but committed and patient with any fumbles or failures.

One performance of the play I remember quite well. I asked for an actor, but no one raised their hand. In a case like this, I just ask if anyone would like to play catch with me. One person volunteered, and I escorted him to the stage, taking his hand.

When I split off from him to the opposite side of the stage to start the game, I turned around to find that he had taken out a sanitary cloth, and he started to wipe down his hands and the baseball glove I had given him. His hands were shaking, like he was rushing to get the glove on. I walked over to him and asked if he was alright, if he actually wanted to do the play. He said, “Yes, I’m ok.” I told him he could go back to his seat and it wouldn’t be a problem, but he wanted to play. I went back to my end of the stage and threw him the first toss.

I saw the audience member awkwardly hold up the glove, palm facing up, the way someone who had never worn a baseball glove before might. I hadn’t thrown the ball hard, but the angle was straight enough that this approach to catching it was not going to work out well. Somehow, though, the audience member blocked the ball with the heel of the glove before it could knock him in the chest, and he dropped the ball. The audience collectively gasped. But he picked up the ball, and threw it back hard, like we were on opposite sides of a stadium instead of barely 20 feet away in a black box theater. I caught it, paused, and asked him, “Have you ever been onstage?” And he said something like, “Not really.”

The play continued on with this person who could barely catch and threw hard enough to take off my head, but was so determined to try, that the audience and I watched in amazement, as he dropped every ball, no matter how soft of a lob I offered up. And with each drop, and each throw, it punctuated our polite little talk about acting and playing.

In the final moments of the play, I ask the audience member, “Do you think I’m acting?” He throws the ball at me, I catch it, and he says, “Yeah.” I pull the ball back, he asks me, “Do you think I’m acting?” I throw him the ball, he opens his eyes wide, into the stage lights and, somehow, he catches it. The audience erupts into applause. “No, I don’t think so.”

KONSTANTIN: (Holding out a paper) Uncle, can you read this? It’s something I wrote a long time ago.

KURT: What? Why. I’m old and tired, and I can’t do anything.

KONSTANTIN: Please, Uncle. I just want to remember what it sounds like.

KURT: OK, fine, let me see here (he takes the paper). “Humans, lions, eagles, partridges, deer, geese, spiders, the fish swimming silent at the bottom of the sea, micro-organisms too small to detect – in a word, everything that lives, everything that has life, everything that is — everything has lived out its cycle and died. In its place, nothing. For thousands of years, the moon has shone down useless on an empty world. The cranes no longer wake and call each other in the meadows. In the lime groves, the May beetles are silent.”

(To Konstantin) Is this supposed to be symbolic?

The most consistent disappointment or frustration I have with live performance, and with actors, is the feeling of not belonging, as if I’m intruding. Like, as an audience member, I shouldn’t be there, that my experience should be as on script as much as anything that’s happening onstage, anything that’s being felt. It’s an odd feeling, one that I struggle with describing, but it’s there 9 out of 10 times I go to the theater. It feels like a shield, between me and the actors’ awareness. I feel it, and I just sit there in the dark, the red exit signs humming into the corners of my eyes.

Sometimes, though, I don’t feel that. In Steppenwolf’s Seagull, Lusia Strus played Konstantin’s acerbic, passionate and attention-grabbing mother, Irina.

In the second half of Seagull, Irina responds to her lover’s plea to “let him go,” essentially asking her to break up with him, because he can’t do it himself. Lusia’s take on this moment was to pause, stare at the other actor, and wait for the whole audience to settle in and hold their breath. The 500-seat capital campaign project of a theater shrinks to the size of a rehearsal room, a church basement. She leans in, the other actor in a wrinkly white shirt, smelling of Febreze and says: “I won’t let you.”

IRINA: You are mine.

You are mine.

This face,

is mine.

These eyes,

are mine.

You’re so talented,

so smart.

You’ll come with me, won’t you?

You won’t ever leave me, will you?

The moment was hushed. Harsh. Weird. Pointed. It was the funniest, most evil thing I had seen in a while. I wanted to burst out laughing, and sob quietly in a corner. I wanted someone in the audience to run out screaming. I wanted the rest of the audience to shake themselves awake from the cocktail they threw down before the lights flickered at the intermission.

As intense as it was, Lusia’s presence felt completely open and generous. She was aware of the audience, welcomed us, and insisted on our attention. It felt like she picked up a conversation, one that would keep going, that I could add to with the next time I was onstage and was called to make something happen. If anything was going to keep me caring about this art, it was this.

This was it. The words, her, and us. And that moment was never coming back.

Kurt’s original two-person show “Unfinished Business,” created with Melinda Jean Myers and presented by Lucky Plush Productions, makes its Chicago premiere October 20-22 at Links Hall, and will be available to live stream anywhere during the final show (10/22 @ 7p-CST/8p-EST). For tickets & info, click here.

About the Author: Kurt Chiang is a theater artist, writer and performer. He is Artistic Director Emeritus & Ensemble of The Neo-Futurist Theater, where he wrote/performed over 300 very short plays in the prolific weekly show, The Infinite Wrench. He continues to write, create, teach, and collaborate with artists and companies in Chicago and elsewhere. Ongoing & Past credits include: The Neo-Futurists, PlayMakers Laboratory, Image Nation: A Tour (w/ Jenna Horton), The Arts Club of Chicago, Lucky Plush Productions, Mocrep, Write Club, The Paper Machete, Free Street Theater, The Annoyance, Salonathon, We Series, Drinking & Writing Theater, The Hypocrites, Woolly Mammoth Theatre, Abrons Art Center, The Theatre School at DePaul University, Lily Mooney, Melinda Jean Myers, Jenna Horton, Hal Baum, Lucas Baisch, Livia Chesley, John Pierson, The NY & SF Neo-Futurists, and as a bedside teaching artist for hospitalized youth with Snow City Arts. He is currently writing and collecting imagery for his project, Chicka-Dee-Dee-Dee!, an original series of videos on grasslands and riparian zones. Headshot by Deidre Huckabay