For those who aren’t convinced of the complexities that abstraction can hold, I offer the work of Jovencio de la Paz to persuade you. Once you get past the boldness of his large fabric or felted surfaces and move through the elegance of overlapping shapes lingering in space, you’ll find something symbolic, celestial, ancestral, and deeply political. The way he approaches form and materials evidences a careful consideration of the heavy repercussions of colonialism and trade, art history, and contemporary life. He takes these anchors and combines them with a personal yet widely relevant symbology that embraces the range of his cultural inheritance. He employs all of it and then some from his perspective as an immigrant to the United States from Singapore, as an artist harnessing the tools of queer aesthetics, and as a maker using materials and processes that have countless generations of makers behind them. The result is a synthesis and translation of a highly personal and global visual language.

After receiving his MFA at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, de la Paz moved to Chicago and continued to investigate fibers and performance through an active studio practice and co-founding the Craft Mystery Cult, a collaborative that seeks to, in short, “remind each body of its own agency”. Somewhat recently, he relocated from Chicago to Eugene, Oregon–a move that has only continued to help him define and refine his craft. He now teaches in and heads the fibers program in the Department of Art at the University of Oregon. Most recently, his show Skin Broken by Prisms closed as the final exhibition for Carl & Sloan Contemporary in Portland.

Just before the opening of his exhibition, we had a conversation about movement and migration, the role of artists and abstraction in revolution, and the poetics embedded in batik’s lost wax process.

Tempestt Hazel: One of my favorite memories of your work is from the time I was at Chicago Artist Coalition some years ago. I would go downstairs when I needed a quiet place and occasionally I would take a peek into your studio. At the time, you were working on large surfaces and creating dozens of tiny icon-like line drawings on them. I would get lost trying to figure out the mythology you were creating and where the motifs and symbols were from. It always felt deeply rooted in a variety of histories along with references to astronomy, ancient glyphs, and navigation. Maybe that’s a good place to start.

Jovencio de la Paz: Those drawings were the first steps to my work in batik and indigo dye. My interest in indigo is very rooted in my lineage in southeast Asia, Indonesia, and Singapore. It is a cash crop that is [connected to] colonialism. The Dutch colonized Indonesia and southeast Asia because they were obsessed with the color blue. When indigo was brought to Europe, it caused an explosion of interest. It was a cash crop of the slave trade in the American south. A huge cash crop of India. It’s a very fascinating and troubled history.

I originally started working with indigo in a really experimental way. I used it for performances with different collaborators. There were layers of information and artifice. But there’s something much more direct about using the material as it’s intended to be used–as dye and fabric.

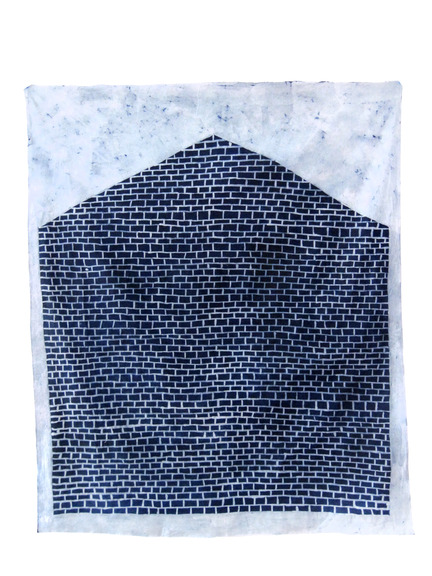

The batik process itself is a process of lost wax. The fabric is white and you paint on the fabric with wax and then dye the fabric and because the wax resist the dye you have a white line on a blue field. That process and technicality has poetics in it. The image is always an absence--[and the process can read as a reference to] absence of homeland or absence of loved ones. There’s always an empty space that I’m trying to articulate.

As an immigrant, I was already thinking about the Pacific Ocean and migration. I was reading Rebecca Solnitz’s Field Guide to Getting Lost. In the essay The Blue of Distance she talks about the horizon and blueness, and the idea that blue is always a place of longing. It spoke to me so powerfully. The batiks became atmospheres referencing being led by the stars or ideas of navigation through constellations. I also made a number of pieces that were in response to violence against people of color and queer individuals that communicated a feeling of emptiness through the process.

TH: I’ve been thinking a lot about movement and migration lately and how being in a new place alters our behavior. I’m curious about how movement, your move from Chicago to Oregon a year ago, has changed your work. Do you think you would be making the work you’re making now if you were still in Chicago?

JdlP: I think about this a lot. Changing the institution I’m affiliated with [changed things for me]. I loved the School of the Art Institute and my colleagues, but there was little access to studio and facilities. We were really stacked on top of each other as faculty trying to have a practice. Being at Chicago Artist Coalition allowed me the space to make those drawings [you mentioned earlier]. I had room to spread out. When I got [to Oregon] it became that experience [at CAC] multiplied. The vastness of the west and the fact that the University of Oregon is a Research 1 institution that supports artist research with funding and space–those factors automatically changed the work. Similarly, after my undergrad when I had zero space the work got smaller and smaller. Space has always been interesting to me as a challenge.

But then there were more esoteric things I found in the difference between Chicago and here. The light is different. And when I got here, I tried to make batiks but couldn’t. It was almost as if the ideas belong to the place of Chicago. I still can’t explain it. [When I got here] I started making batiks that were line drawings of brick walls. They really brought that body of work, the batik and indigo work, to a close. I think it had something to do with the fact that I grew up in Oregon. My family is here. [When I came back] the question of longing for loved ones was answered. It was resolved in my life. I still love making batiks, but the subject has changed.

TH: What has it changed to?

JdlP: When I got here I spent time in nature constantly. I started traveling so that I could see the landscape. [During my travel] I became really interested in petroglyph sites–13,000 to 15,000 year old rock drawings, signs of ancient migration and waypoints that are found down the center of the state. They were amazing to see because they looked very familiar to me. Theory says that when ancient Asians from Northern Asia crossed the Bering Strait into America and migrated down to South America, they would leave markers for each other. These drawings tell a migrant story of a time before borders, a different reality of movement.

This was a really important moment for me as I began a new body of work that included more color and was based in a personal symbology.

TH: What does that personal symbology look like? Where does it come from?

JdlP: With the batiks I could go through and describe the illustrations or tell the meaning behind them but I don’t think that actually tells you much more about the work. There are a lot of symbols of the body and references to trauma. I use a lot of figures that are moving through space. There are references to constellations and architecture. I come from a family of architects, so ideas of place and placelessness or navigating and organizing space are in there.

Recently, the work has become much more abstract. Late Night/Even Later are two works that are basically identical. I used the same stencils, so they’re very similar. [When I’m making the stencils] I may think of a shape as an eyelid. Or a red moon. I made these the day the shooting in Orlando happened, [so the red moon is my reference to that]. This is what I mean by a personal symbology. I don’t think this shape necessarily reads as an eyelid [or the other as a moon]. It could be read as many different things. But that’s what was in my mind.

Or, I’ve been working on these sculptural pieces–steel, bent posts. I think of them as hair. In reality it’s just a black mark, but I think of it as hair. Personal symbology. The mark, though it’s extremely simplified, it comes out of a kind of symbolic reality. It’s very representational to me.

TH: When you talk about the work, do you find yourself doing a direct translation of the symbols?

JdlP: It depends on to whom I’m talking. People often read the work as purely formal. I like that. I like trying to find the political in the formal. Indigo, for example, is exactly that. The conversation I want to have is situated in how a formal concern can be a political concern.

TH: Your practice, in many ways, is a reminder of how formal and abstract art has a place in political conversations. There’s something about work that pulls you in then makes you realize or remember that these forms, colors, materials, and gestures come with a history and often some baggage. I gravitate toward work like that, which attempts to make us confront that–artists like Jack Whitten, Doris Salcedo, or Martin Puryear come to mind.

JdlP: Martin Puryear is an artist I think about a lot. People often ask me whether or not I think the politic would be more actively served if I did activist work. They ask, “What is the place of painting in these difficult times?” I think that’s a really hard question. I understand where they’re coming from. When I was in grad school I had friends doing social practice and organizing–they were doing amazing work. I always felt guilty for wanting to make beautiful things. And I tried to understand what that was about. I love [Jacques] Rancière’s The Nights of Labor (La Nuit des Proletaires). In it he talks about how revolutions don’t happen through a single, uniform front. Revolution has a spirit. But we tend to get obsessed with language, law, and things that are litigious. [When that happens], activism starts to have fewer and fewer dimensions in popular culture. If something can’t be immediately read as a politic, it’s often dismissed.

For me, the studio is such a closed space. The activism I participate in is not in the studio. In the studio I’m more reflective. Once it leaves the studio, I hope it can enter the world in a multi-pronged way. I want it to be beautiful and visually arresting. I want that experience to lead to other possibilities of thinking. A lot of this work is violent visually and that’s important. It references the kind of physical trauma that’s happening in our country. They are paralleled.

TH: I think it’s important to have objects that serve as documents. I see your work as an addition to our moment’s documents and it serves a different purpose within that context. It’s not policy or legislation. It’s not a sign at an action or protest. But similar to the rock drawings that you spoke of before, I think art helps to push us forward while serving as a record for those who come after to reference. And like you said, change happens through a variety of approaches. Your approach functions in a different space (the art space) where sometimes laying it out literally doesn’t work very well and some people might tune out from a heavy handed message. I don’t subscribe to the thought that art falls short as activism at the fever pitch moments of tension and change. There are people for which art–in its many forms–is an effective way to reach them. Maybe the impact just isn’t as immediately evident.

JdlP: I’ve always seen the nature of textile as very political. Partly because it resists being singular. I’m interested in the fact that my works read as paintings, but they are clearly not painted. They’re not on canvas, and I don’t use paint. The work can move between identities and between contexts. I think that’s a good thing. It’s generative.

[For instance], using felt allows me to cut surfaces in ways that can’t be done with canvas. It can take different shapes that are maybe trying to be like a rectangle or a triangle, but not quite. That contour is really important because there’s something irregular or somatic about it. The felt is a bodily material, and that’s very charged language. But that’s also in the material. It’s not a reference to those ideas, it’s actually in the material in the same way that the blue of indigo is. It is itself an embodiment of colonialism and bodies under distress. And that’s a very textile way of looking at things.

TH: When did you move to making work on irregularly-shaped surfaces?

JdlP: Textile is an interesting thing to study because it offers you so many histories that are different from Western canon painting. You look at different objects and trajectories when thinking about art and materials.

Two things that impacted me when I was an undergrad at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago were Leon Glob’s paintings, which are very active and violent surfaces stretched in bizarre ways, sometimes with areas completely cut out or missing. The second was a Pawnee star chart at the Field Museum, I believe it was on rawhide. These two things were both transcendent visual experiences and linked to me somehow. They both deal with violence, but also a kind of hopefulness. They are both paintings but they aren’t in a rectilinear shape. [To me] they always felt more like objects or bodies.

In weaving, when you’re not a great weaver, the edges of your fabric are all wonky. I think it’s beautiful when I see my students try to find their body while weaving. Their moves are recorded. Every thread is a record of each moment and creates a timeline of activity. Then, as they get better the wonkiness in the edges goes away. Weaving shows how the grid of textile can be stressed by the body. I’m trying to create that [reflection of the body and irregularity] within my work, though it comes and goes.

TH: Do you use weaving in your work often?

JdlP: Almost never. I know so many incredible, incredible weavers and I’d much rather see the world populated by their weavings and not my own. But I weave as a kind of discipline, or a way to focus on the studio. Also, there’s a big part of contemporary art and craft devoted to sustainable production and revisiting how things were made traditionally. I don’t make things traditionally. I’m not interested in making a product in that way. But I’m interested in studying weaving in order to learn more about material culture, about the names of the places where products and materials come from, or the stories of people who brought it from point A to point B–those histories are really productive for how I view culture.

TH: Finally, I want to ask you about teaching. What relationship does it have to your practice?

JdlP: It is incredibly important. I talk with my colleagues about how people don’t really want to talk about teaching [in relation to their practice] because it’s so impactful but also a completely different terrain of thought. I don’t think it influences what I want to make. But it influences my attitude and how I handle myself as a person. One of the beautiful things about craft and teaching textile that I think about often is how, [for example], weaving is a 40,000 year old practice. The technology has changed some but the principles, for the most part, have stayed the same. As a weaving teacher I get to be one of the most recent human beings in this incredibly vast history of people to share this information with another group of people. It’s humbling. I think that’s really important as an artist–to see a picture that is larger than your studio and immediate art community, larger than the art world or art market, larger than the critical apparatus, and to see yourself as part of a community of humanity. That’s what it’s about for me when I’m teaching. It becomes a kind of simultaneous connection to history and the future. And I’m in the middle of it.

_

Feature Image: Late Night/Even Later, Screen-Print, mono-print and acrylic on wool, 94″ x 64″, 2016.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com