The colorful folded paper triangle takeaways prepared by Hương Ngô’s for her current exhibition “In the Shadow of the Future” open up to describe a narrative about Vietnamese fighter pilot Phạm Tuân heading to space under a Soviet program in 1979, the same year that thousands of people fled persecution in Vietnam to resettle in a suburb of Paris. Hương brings these two migration stories together under the same roof, connecting their journeys after 40 years of separation.

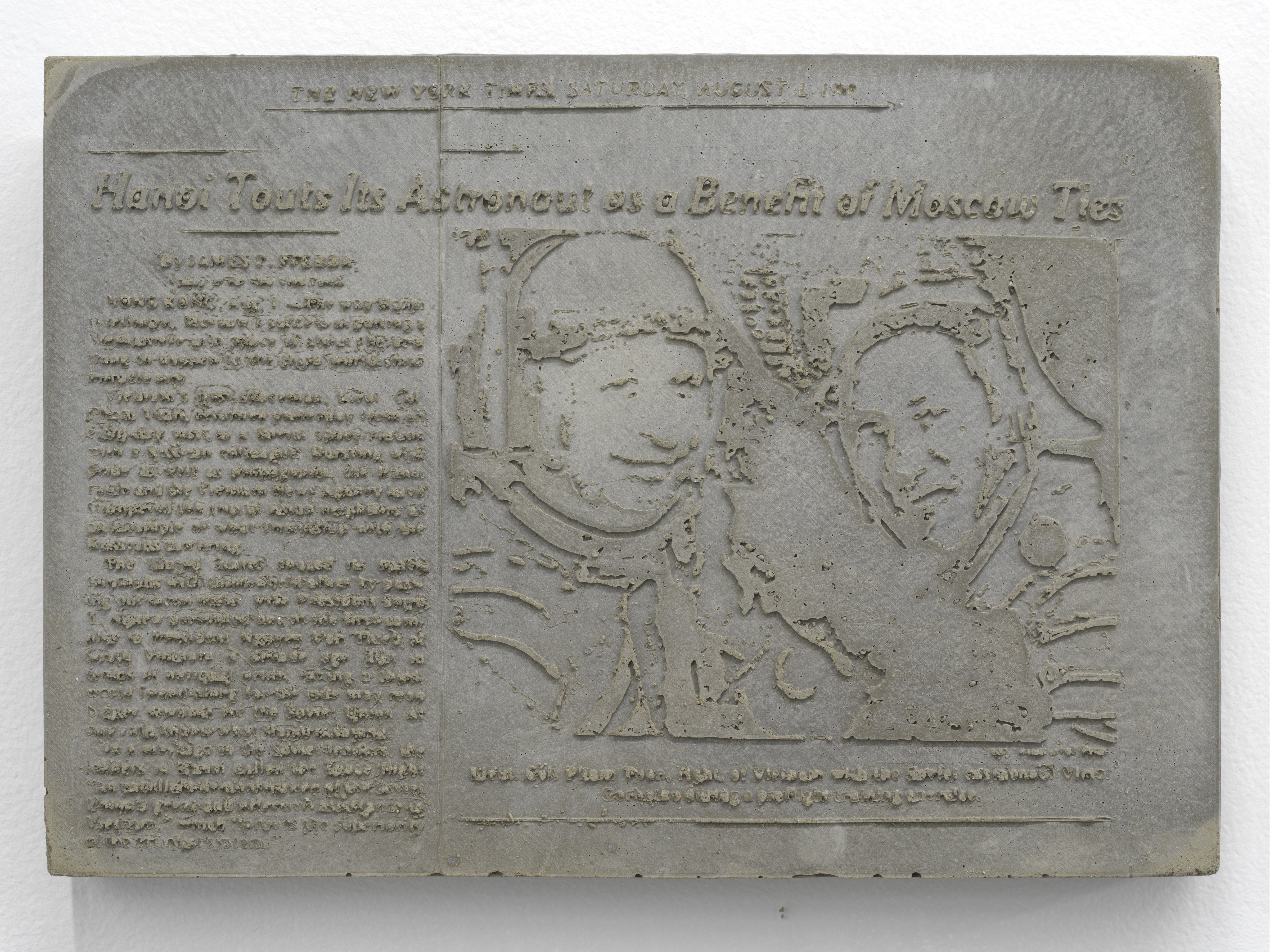

In the center of the room at 4th Ward Project Space, is a bright architectural installation made of collided triangular forms. Some have windows, and others are closed off in their own corners and have gardens of greenery. Two video screens protrude from the top of the piece, tilted up to the sky, and another is ingrained into the building itself, posited inches from the ground. On the wall of the gallery is a newspaper article cast in concrete from the New York Times regarding Phạm’s mission with the text slightly deteriorated.

The environment constructed by Hương felt really social, vivacious. I felt like I was looking at a diorama of a bright, clean triangular home with nice landscaping and room for community mingling. The sterile aesthetic furthered the idea in my head that this was a biology lab where we are invited to look under a microscope to view a complex organism; the ways in which it grows and how its pieces function within it. On the way out of the exhibition, I ascended up a couple of stairs to the shared garden space complete with a picnic bench, and eventually out to the sidewalk, leaving the installation below the rafters. For my first visit to 4th Ward Project Space, I left feeling like the installation, inspired by social housing, mimicked the art space itself.

This interview took place via email and has been edited for clarity. It was spurred by Hương Ngô’s current show “In the Shadow of the Future” that runs at 4th Ward Project Space until May 12, 2019.

Hương Ngô: My installation was based on the star-shaped architecture of Renée Gailhoustet and Jean Renaudie in Ivry-sur-Seine. Renaudie, especially, was inspired by natural patterns of growth and thought of the city as a living organism. He was adamant about each apartment in the housing project having a garden, which would be the point of exchange between/amongst neighbors. You might even say that they were opportunities for encounter or even invasion.

Maya Simkin: The installation is mostly seen by looking down into it, a unique perspective for how we usually see urban architectural forms (as well as many traditional forms of art). I interpreted this as a view from the cosmos, from the eyes of someone like Phạm Tuân, watching a different kind of migration happen beneath him on Earth. Can you elaborate on the vantage point of the viewer in this installation?

HN: Phạm’s experience of seeing Vietnam from space was similar to the perspectival shift often offered at World’s Fairs via panoramas, bird’s eye views, or as the case of the Colonial Exposition, miniature architecture, not just in a fundamentally different phenomenological experience but also in carrying the extra weight of national identity, heavier perhaps for Phạm’s newly formed country.

I later learned when Phạm was looking down at Vietnam from space, he was making a map of its terrain. The colonialist implications of this practice, that can also be thought of as making a diorama of a space or a representation of it, make me wonder if it’s the perspective of viewing from top to bottom and zoomed all the way out, that can conjure problematic map making. For example, if maps represent people, what does it mean for Phạm to be making an image that, if looked at more closely is rapidly changing as people are fleeing the country? Hương described that she intended for there to be multiple viewpoints to access this array of narratives- not just the vertical one of a cosmonaut, but one that requires the viewer to walk around the whole piece, bend down, look into, as well as down upon. Perhaps it is with these multiple viewpoints that a singular narrative of domination can be avoided or subverted.

HN: The panoptic view that I was most intent on creating was of these different historical events that happened at roughly the same time represented in the multi-channel video by news footage from Vietnamese refugees resettling in camps in France, inhabitants of Ivry-sur-Seine guiding the viewer through their living space, historical footage of Phạm Tuân, and finally re-performed and imagined moments where the historical figure of Phạm collides with these futuristic ruins.

MS: Do you expect the viewer to take a fictional historic role when interacting with the piece?

HN: I don’t know if I expect the viewer to take a fictional historic role, but perhaps my hope is to get closer to clarity through complexity – in other words to reach across cultural and temporal differences in a way that is only possible from positioning oneself in the present and looking backwards and forwards at the same time.

What interested me the most about the use of plants in this installation was that the list of mediums made it clear that both invasive and non-invasive (sometimes referred to as native) species were used. Unlike in a natural environment where a newly planted invasive species would essentially colonize the area, in this installation, the plants were all in pots with borders that hindered from taking up each other’s space. The pots had varying degrees of permeability from hypertufa to aluminum, and while some leaves and stems of plants touched each other, their roots were left independent and isolated inside their own protective membrane.

MS: Can you explain the decision to have this artificially built environment for the plants and its relationship to the rest of the installation? Do the vessels function to hinder “integration” or are they necessary to facilitate coexistence?

HN: My parents always gardened and I remembered these aggressive vines that would grow every summer. These plants would take over the roses or anything around them growing inches, maybe a whole foot, a day. To them, they were plants that reminded them of home while also providing fresh, nutritious food for their family. One in particular, called bitter melon, is especially gnarly – it has bumps all over and looks like the evil villain of all gourds. I don’t especially enjoy eating it but I can spot it a mile away. I remember seeing it planted in a community garden in Brooklyn even before seeing the Asian auntie who was growing it.

If planted in the wild under the right conditions, it could become “invasive.” Growing up in the American south, I remember all of our highway roadsides draped in Kudzu (a creeping vine) and the myths surrounding this plant; some people said that you could hear it grow, calling it “the vine that ate the south.” In truth, the plant is not as sinister as we have been led to believe and its proliferation was encouraged as a means to stop erosion and provided people with work following the Great Depression.

It has always struck me that many Asian flora and fauna, exported quite unnaturally and often intentionally because of their positive qualities, then become “invasive,” but often still identified as being Asian instead of shedding their origins like their European counterparts. Take the Asian Carp, for example, which were introduced to control weeds and parasites in aqua farms and are now threatening species from the Mississippi to the Great Lakes.

This contentious labeling and revaluing of flora and fauna is an area which lies at the intersection of my interests in language, migration, and my background in biology. We can see it play out in the way that migrants are often described as swarms or invasions, like in the most recent migrant caravan from Central America. A focus on control diverts our attention away from the actual crisis, which often explains the origins of migration.

MS: How do you shape the roles of invasive/native plants in the context of Vietnamese immigrants in Paris?

HN: I wouldn’t say that the plants represent a certain people in my installation, but the same ideologies are working on both in the way that we perceive and value them. The banlieues outside of Paris are known for housing immigrant populations, many displaced as a result of France’s history of colonization and spoken about in not dissimilar ways to how those in the migrant caravan were described.

I received these plants as gifts or through exchanges. I like that the viewer might not know which plants are invasive or not and also that ideas of friendship or exchange might have some kind of invasive potential for proliferation.

Another plant in the exhibition is less evident than the potted ones. This one is featured in the videos on a petri dish as well as on the exhibition materials. It begins as just a few cells and then grows rapidly in the container, an abstracted moment. Without knowing what the substance was, I immediately thought that this was a sign of colonization, a disease started in a lab that can’t be contained maybe. I forgot the possibility that growth and expansion can be a sign of prosperity, something amicable, or budding.

HN: Azolla was a plant that Pham brought into space. Different species grow indigenously around the world and have been viewed as both invasive species and as superfoods (either in their capacity as feed for livestock, fertilizer, or possibly even human food). Every once in a while, someone gets hyped about Azolla and thinks it will solve all of the world’s hunger problems. I found out that there was even a book written in 540 A.D called The Art of Feeding the People by Jia Ssu Hsieh (Jia Si Xue) that delves into the cultivation of the plant as biofertilizer.

I’ve tried growing the stuff several times, but it never works for me, so I will call it neither a superfood nor an invasive species, but I think it’s beautiful and reminds me of the fractal growths of Gailhoustet and Renaudie’s star-shaped architecture.

MS: The plants also made me think about how in the past you have worked with thermo-responsive materials that reveal information when touched by warmth – as plants are living and breathing and require nurture and attention and warmth and likewise are fruitful with what they give when paid attention to. Can you speak to a potential theme of care or attention within your work as a method of accessing knowledge?

HN: I definitely consider our histories as living and changing and I seek out material evidence of this idea in spaces like archives or ruins. From projects like “To Name It Is to See It” (DePaul Art Museum, 2017) and “Reap the Whirlwind” (Aspect Ratio, 2018), for which I was working in national archives in France and Vietnam, I witnessed the presence of past researchers through palimpsests of notes that they had made, pages that they had rearranged, worn down, or pinned and re-pinned in slightly different places.

The presence and care of archivists is apparent in those sites. In this era of digitization of archival materials, there are new signs of care and attention or lack thereof. Chunks of archives might get scanned, fail to be scanned, scanned at a low quality or without consideration of marginalia that are often important to researchers and artists. While digitization is meant to increase accessibility, it is often also an excuse to reduce accessibility of the original to a larger public, which is often argued to be in the interest of the care of the archive. I think this warrants a rethinking of care – is preservation of the document prioritized over knowledge potentially garnered from an unmediated interaction with it?

When I am in Paris, I always make a visit to the Palais de la Porte Dorée and the nearby Bois de Vincennes, located not to far from Ivry-sur-Seine. These are spaces that were built to house the Colonial Expositions of 1907 and 1931. Bois de Vincennes is a sprawling park where you can still find miniature examples of vernacular architectural models of former French colonies and exotic gardens, and be haunted by its former human zoos. Besides minimal upkeep, the site has mostly been left to fall into ruins, letting its history build up like the palimpsest of researchers’ marks on archival documents. Achille Mbembe has written about this tension between the materiality of the archive and the power to allow for decay. “The final destination of the archive is,” Mbembe writes, “[…] always situated outside its own materiality.” Thus, it is the collective memory to which we should prioritize our care and attention.

MS: In many other forms of migration, including the narrative you present in this exhibition, migrants fuel efforts into a new home that is characteristic of them and their new lives – by emphasizing the architecture of the physical living space, it seems to be important to have a home or rootedness. How do you think space and this particular narrative of a cosmonaut haunting his peoples’ new settlement conflicts or extends this tendency?

HN: I’m hoping that it complicates both narratives. The fact that these events coexisted at the same time is amazing to me, as the enduring representation of Vietnamese people is that of refugees and/or as timeless, othered peoples (as often happens with those who were colonized or exoticized). Seeing that these different experiences of Vietnamese people were happening at the same time hopefully makes us question any kind of monolithic representation. Phạm’s feat was not universally celebrated, by the way. Far from it. In the US (as you can see from the NY Times article cast in concrete), it was reduced to a mere propaganda campaign with purely political value. In Vietnam, the phrase “We have no rice, we have no noodles, so why are you going into space Mr Tuân?” circulated widely, mirroring the questioning of the space program in the US by people of color in defunded city centers.

MS: Do you think outer space presents an opportunity for identity to be deterritorialized?

HN: The Intercosmos program definitely fits into a Star Trek mode of multiculturalism but one which cannot and does not wish to shed its roots in national identity. But maybe an important aspect to deterritorializing or decolonizing space exploration is to first acknowledge how our space programs have always situated themselves in colonial and militaristic ideology.

In experiencing this installation and looking at Hương’s other works, I constantly felt the bearing presence of history and future and their interplays and performances. The title of the show, In the Shadow of the Future, is exactly what the environment felt like. Different from “the past,” the shadow of the future is something actively cast, existing only insofar as the future is there to cast it.

MS: When you worked with youth in France to create this narrative of a historical ghost, how do you think different timescapes interacted with one another? Do you think your use of archival materials (as well as materials you’ve created that can mimic archival ones) and research serves a performative function?

HN: Working with UJVF – yes they were performing the role of Phạm Tuân but also performing what it means to be Vietnamese, something that is actually still new and in flux in French culture. In France, it is recent for one to identify as anything other than French. Hyphenated identities don’t exist. To suggest that you are French-Vietnamese, you would say, “Je suis française, d’origine vietnamienne/ I am French, of Vietnamese origin.” Temporally, they do not coexist as the French way of expressing identity is based on nationality, not ethnic origins – French is what you are, Vietnamese is what you were. So, this group that I worked with are practicing and exploring what it means to express a Vietnamese identity. In the parade that we were part of (not all of the footage which is included in the video) members of the group (UGVF and UJVF) were dressed in clothing and playing instruments from ethnic minorities, áo dài (a national dress of Vietnam), and younger folks wore shimmery motorbike shirts more similar to the street clothes you would see today. It was a messy mash-up, but that is the reality of identity.

I should also mention that UGVF and UJVF do not represent all of the Vietnamese community in France. UJVF was started by Hồ Chí Minh when he was studying in France, and UGVF is, while not directly connected to the current Vietnamese government, they are “friendly,” let’s just say. Gisèle Bousquet’s ethnography Behind the Bamboo Hedge goes into detail about the different waves of immigration from Vietnam to France and divisions that still exist today. So the performance of Phạm Tuân also expresses a crossing of political lines – someone lauded by the communist party who performs the experience of an exile.

MS: Thank you so much for these generous and thoughtful responses. Do you have any summer plans you’re looking forward to?

HN: I’m expecting! I’m due in June, so after my spring teaching and exhibitions finish, you can find me in the pool everyday until the baby comes. I’m excited to have some time to reflect on past projects, dream about the future, and get to know this new creature in my life.

Hương Ngô’s upcoming exhibitions:

“The Warmth of Other Suns” Phillips Collection, Washington DC. June 22-Sept 22, 2019. In collaboration with Hồng-Ân Trương.

Contemporary Artists Reflect on the American War, Minneapolis Institute of Art. Opening Sept 28. In collaboration with Hồng-Ân Trương.

Solo Exhibition. University of Illinois Springfield Visual Arts Gallery. Oct 24 – Nov 21, 2019.

Featured Image: Video still of a figure dressed in a white cosmonaut suit. The figure stands outside standing in front of a multi-level tan building with lush plants dangling from the windows. Next to the figure is a large white geometric structure that comes to multiple points high above the figure’s head. The top half of a tall tree peeks out from behind the structure. Image courtesy of the artist.

Maya Simkin is currently interested in city mapping, using interview as a medium, beekeeping, geopolitical surveillance, and exploring a queer post-Soviet Jewish culture. Maya obtained their BA at American University and MA at the University of Westminster and once made delicious elder flower cordial in rural Bulgaria.