Thursday, July 3rd: Day One

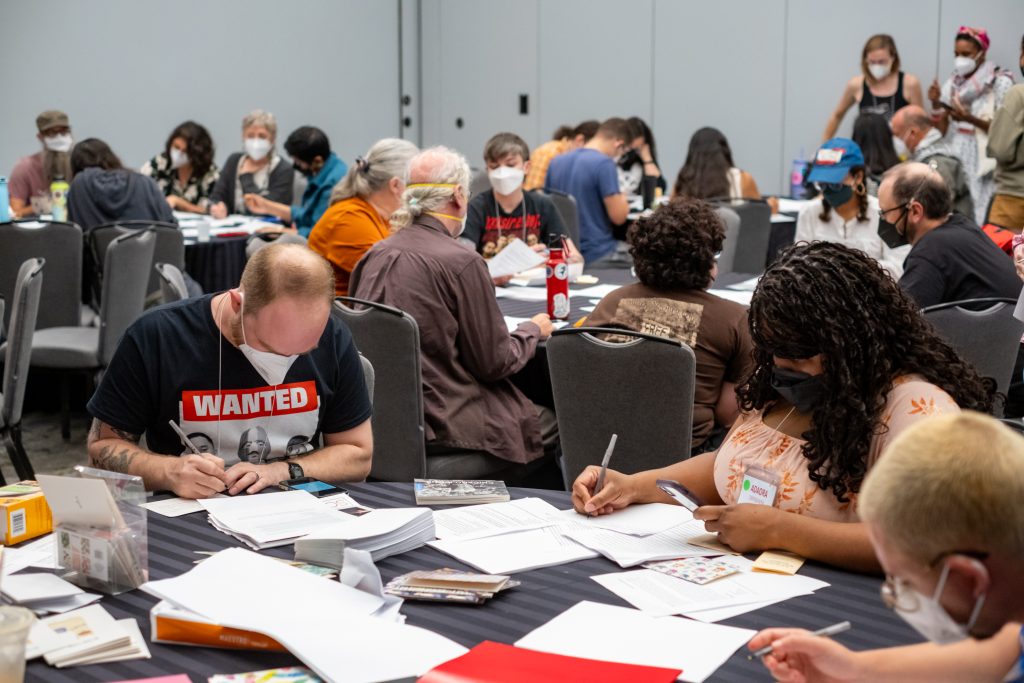

2:15 pm: The McCormick Place convention center is a behemoth grey compound overrun with leftists, all toting red-bordered name tags in plastic sleeves around their necks. It has a back-to-school energy. Attendees with fresh notebooks excitedly flip through a magazine-thick catalog of events. The line for registration is buzzing, and I recognize a couple of familiar names. After picking up my badge, I go to the end of a long, aggressively air-conditioned hallway to find my first session, and am relieved to see Anna in the front row. A friendly face is like an anchor while I’m adjusting to being in a sea of strangers. She asks if I want to sit together (of course I do). We chat for fifteen minutes before she tells me I’m in the wrong room and redirects me.

2:30 pm: AI and the Technofascist Power Grab for Our Data, Lives, and Resources.

Now in the correct room, I realize I don’t know much about how AI has progressed, even though it is an existential threat to me as a writer. I hope this panel will give me some insight and good talking points, because AI has become a frequent topic of conversation in my daily life.

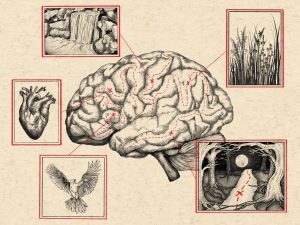

The panelists (Myaisha Hayes from MediaJustice; Alli Finn from AI Now; and Irna Landrum, former Kairos fellow) introduce themselves and put us in a group activity to talk to the people around us about how AI is impacting our lives. Next to me are a grad student from Chicago, a lawyer from Michigan, and a guy who runs co-ops and traveled here from Oregon. I mention the AI-generated summer reading list the Chicago Sun-Times ran a couple of months ago full of books that don’t exist; Mike talks about lawyers who file cases with bogus AI citations; another person chimes in to talk about how an AI medical scribe was used without their knowledge while they were getting their hormones, a worrisome blurring of patient privacy while US officials attempt to criminalize trans healthcare; an older woman joins our group and mentions the recent MIT study about ChatGPT’s effect on our brains, with regular usage causing a steep decline in cognitive function. I’m dangerously close to spinning out about how bad things are and ready to hear from the panelists.

Alli Finn goes to the basics first, tracing how exactly we got to the point where AI feels like such an inescapable beast. Finn tells us that “AI” is slippery to define because the term is ultimately just a marketing strategy: there are many different kinds of technology (machine learning, algorithmic, generative AI, etc.) being sold by Big Tech as part of the same unstoppable future. These companies are selling a bogus speculative future where AI inevitably takes over many of our functions, a false promise like so many other empty marketing schemes.

Finn wants the audience to understand AI is a deeply personal issue: this technology requires massive amounts of data and infrastructure, all of which are being taken from us. Every article I’ve published and post I’ve made is being scraped from the internet and fed to a hungry monster. Even this essay will eventually be slurped up by the clumsy behemoth that is ChatGPT. Right now, that’s where things stand, but we are at a pivotal point in the development of AI where it isn’t too late to put in place regulatory precedents protecting us as consumers and creators. In a big win, tech giant Anthropic recently had to settle a major lawsuit brought by authors for intellectual theft as their books were used to train AI without consent; there are ways to protect your data privacy to some extent; and above all, we can eschew the narratives that OpenAI has been spinning about what the future must hold.

A local organizer closes out the panel and highlights Chicago as a place where activists have successfully made a difference countering nefarious uses of AI, such as pushing to end ShotSpotter and the ACLU’s win restricting uses of Clearview AI facial recognition technology. The room gives a round of applause, and I’m grateful to live in a place where people see hope and where we are lucky to have such powerful organizers.

A text from Amélie: I’m tabling in Grant Park C all day, if you want to come visit?

4:10 pm: I find Amélie in a room where dozens of organizations are peddling stickers, zines, buttons, and a contagious enthusiasm for each of their specific causes, from freeing Kashmir to protecting social justice in academia. I run into a couple of my bookstore regulars, which I suppose I should have expected, and realize one is an editor for In These Times when he’s not busy playing the background role of “bookstore customer.” I pick up their special culture issue, and talk to the culture editor, Sherrell Barbee, about how their work is typically relegated to a minor section in the magazine. She’s the first fellow arts journalist I’ve encountered so far, and it is a bit of a relief—I’ve struggled at times to explain why it’s important that I’m here at this conference, when my typical beat is not socialist politics (though there’s still plenty of time to expand).

Waiting for the next panel, I read from her editor’s note at the start of this issue: I believe in art, music, literature, film, theater, dance and comedy. I believe these expressions of life, these gifts we give and these ways we show up for each other, can bring us closer to the future of our revolutionary dreams — or be weaponized to do the opposite.

4:30 pm: Art and Communism

Anna is already in this room, so I join her. People slowly pour in until there’s standing room only, because film director and musician Boots Riley is on this panel.

4:45 pm: Boots Riley is running late (the cursed NASCAR race through downtown Chicago made traffic horrendous). Most people decide to wait, Anna and I included. We try talking to the people behind us, two adults and a tween from Evanston. I try to engage with the young person by asking him if there are any panels he’s excited for, but he seems freaked out that someone asked him a direct question. My bad.

5:00 pm: Boots Riley finally arrives, and it’s clear he has a friendly rapport and long history with his interlocutor, the educator and organizer Jesse Hagopian. He says that the place of artists in the movement is to create feelings in audiences that spark them toward action. He also recounts how much his art has changed as he learned what galvanizes people: for example, at the start of his music career, he refused to have choruses on his songs because it felt like “selling out.” Over time, he realized that to make art that impacts the masses, you have to make art that mainstream people want to consume, which means songs with catchy choruses.

It’s a helpful reminder that making art popular can be a prerequisite to having a major political impact. He reflects on how one of the more meaningful moments in his career was realizing that the flashy satirical film Sorry to Bother You, which was about unionizing a call center in dystopian California, inspired people to organize in their real-life workplaces. Hagopian describes The Coup’s music as making people “dance like liberation is possible,” which makes me think of the In These Times article I’d been reading just before, where Barbee tells us that the gifts we give through art can “bring us closer to our revolutionary dreams.”

Boots shares he believes art must be accessible and explicit. For example, he takes issue with valorizing protest art like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, criticizing its vague anti-war sentiment with lack of specificity. It isn’t enough to say that “war is bad.” Of course, most people don’t think war is good. To truly make “communist art,” we have to name for our audiences that the American government is continuously enacting violence upon people at home and abroad, which Gaye failed to do.

6:15 pm: Conference organizers allowed the session to go late because of Boots’ delayed arrival, so Anna and I are now very hungry. We find Emma and J who went to a different session, and I steward them to Golden Bull. My fortune cookie says “It’s time to try something new.”

9:00 pm: I try going to Radical Trivia with J, but we are separated since two different teams need an extra person. I lose steam and have a long Red Line journey ahead of me, so I go home. J later texts me that the team I was assigned to ultimately won, but I needed the rest. This was only Day One, after all.

Friday, July 4th: Day Two

9:30 am: Emma and I decide to split a Lyft from our neighborhood. I hit my head getting into the car. There’s more NASCAR traffic. Unlucky start to the day!

10:00 am: Gender and the Rising Right

We arrive out of breath, but on time. My boss from the bookstore is knitting in the audience, and I’m glad to see them. I’m distracted at first by Sophie Lewis’ charming accent—a dainty blend of French, German, and British—but it passes. The panel features her, Rae Garringer (author of Country Queers), Andrea Ritchie, and Janelle Hope. All of the panelists are brilliant in their own ways: Janelle Hope gives a very academic but interesting historical introduction about Ida B. Wells and the Black anti-fascist tradition; Rae Garringer shares their experience living and researching in rural West Virginia; and Sophie Lewis goes over some talking points I recognize from her article about UK TERF-ism in Lux Magazine, TERF Island. It’s a constellation of rich topics which are all fundamentally interlocked, but 90 minutes clearly isn’t long enough to get into much of a dialogue with each other—most of it is spent on each individual summarizing their own work.

Garringer points out that the terrifying “MAGA Budget Bill” looming in the background of this day threatens resources that never existed in West Virginia to begin with. They say they’ve never had a trans-affirming doctor, the closest hospital is hours away, and they already have to rely heavily on their community to meet basic needs, emphasizing that queer people in red states have been “in this moment” for decades.

My favorite takeaway here is Sophie Lewis talking about the need to make leftism sexy to counter the seductive pull of being a “tradwife,” or a woman who embraces “traditional” gender roles in exchange for economic independence. Lewis argues we need to “libidinally recruit” people by showing them our values of interdependence are joyful and pleasurable, not just militant and righteous. I think she has a point, and I think art is one of the sexiest things about commitment to liberation! What got me invested in a fight for queer liberation wasn’t initially the theorists—it was things like the hot, tender romance in Giovanni’s Room or the signature disobedience of Ren Hang photographing queer bodies. I’m not sure exactly how I will go about “libidinally recruiting” people to the cause, but it’s a compelling question to reflect on how I did end up with the beliefs and political commitments I do.

11:45 am: I am startled while leaving the bathroom by someone calling my name. Turns out to be one of Sixty Inches From Center’s founders, Tempestt Hazel—this conference has been full of happy run-ins.

3:00 pm: The Role of Black Media Under Fascism

There are very few white people in this room, which makes me wonder whether they are disinterested in Black media generally, but I am also relieved to be in a space that is less overwhelmingly white. This might be the only panel at the conference like that, aside from the affinity mixers.

The panelists (Da’Shaun Harrison, Tea Troutman, Ko Bragg, and Aurielle Marie) are all connected through Scalawag Magazine. They are clearly having fun engaging with and pushing back on one another—Aurielle encourages the audience to “surround yourself with people who sharpen you and love you enough to call you out.” and it’s clear that these friends do that for each other in the way they debate the ethical questions we are always grappling with in journalism while knowing that they share the same passion for producing impactful, progressive media. Troutman and Marie have a back-and-forth on their feelings about the concept of “rigor” in journalism, with Maria saying it’s a tool of white institutions to invalidate journalism done outside of standard media practices, while Troutman values the framework a bit more.

Tea Troutman is harshly critical of “representation politics,” claiming that “representation in media is a sedative balm so we do anything but revolt.” She suggests that Hollywood, which I take to refer to the sprawling media industry in general, is simply allowing those who are oppressed to “create the films and soundtracks” to backdrop their struggle. I wish that I could see what a dialogue between her and the Hollywood-steeped Boots Riley around the purpose of Black media would look like.

5:00 pm: Reclaiming the Future: Outer Space as a Site of Organizing and Imagination

I’ll be honest: I am very unfamiliar with outer space, it has never been one of my special interests. But there isn’t another arts-related session during this part of the conference, and J endearingly loves space. I like to take an interest in the interests of my friends, so I come to see Chandra Prescod-Weinstein and Lucian Walkowicz, and am surprised to find that art comes up quite a lot.

The intersections of art and astronomy are ones I’ve never spent much time considering before, but Prescod-Weinstein makes a compelling case about how our relationships as humans to the night sky and the stories we tell about it are some of the oldest and most sacred. She discusses how cutting people off from access to the sky (especially in settings of incarceration) is a particularly cruel estrangement from our sense of humanity.

The imaginative aspect of outer space fascinates me and the panelists—Prescod-Weinstein talks about how the popularity of early science fiction novels like Alexander Bogdanov’s Red Star are what initially garnered public support for research into outer space. This also makes me think back to the discussion I had after Boots Riley’s talk: art really does shape where public support goes, and if we want to make art in service of the movement, it is our responsibility to consider how our work will do that.

Going into a session knowing almost nothing and coming out feeling energized about what I learned is one of the best conference experiences to end the day on.

Saturday, July 5th: Day Three

This panel is all about print media in a world where the internet “for all its underground potential, has become privatized, bordered, and unfree.” It is driving many journalists and others toward printed matter and analog ways of organizing and getting information.

Tracy Rosenthal is here representing WAWOG’s The New York War Crimes, a faux New York Times-style print publication that’s been all around the conference. The paper’s initial draw really is in its replica NYT format, which goes to show the gravitas that a simple typeface can have. That authoritative Cheltenham headline font harnesses such an authoritative institutional power that by the time you realize you’re reading a different paper, you’ve already bought into its legitimacy. I’ve always wondered how they got the NYT typeface and layout with the myriad copyright barriers I’m sure are protecting it, and Tracy tells us that basically they had a writer involved with access through work. They say this is a great example of the media worker’s power, and specifically that “we are the ones who have been making legacy media possible, and there are ways we can mess with it given those resources.” The many New York-based people in the crowd and on the panel are riding the high of Zohran Mamdani’s win in the face of negative spins from legacy media outlets. To them, this is a signal that independent news media matters, and can be more powerful than the backing of billionaires that Andrew Cuomo had.

A representative from Radar Collective digs into the importance of aesthetic and design for some newer publications like theirs. Influenced by the short-lived but influential Tricontinental publication of the 1960s, you can see the direct use of similarly powerful visual language of militancy with saturated colors depicting skateboarders. I think back to what Sophie Lewis said yesterday about making leftism sexy again, and Radar’s visuals draw me in on that level. Documenting revolutionary history has to be more than rigorously written to draw people in—it has to be beautiful.

Sunday, July 6th: Closing Plenary

I ask if Anna, J, M, S, or Emma will be coming to the closing plenary, but everyone else is too drained from the last three days. The last man standing, I hop on the red line to McCormick Place for the final time this summer to see the closing plenary led by Silky Shah, Eman Abdelhadi, Mikaela Loach, Scout Bratt. They thank the various organizations that make the conference possible—including the folks who ran the free childcare provided throughout the conference, making it possible for many parents to join. The speakers, when giving their closing remarks, all use some protest chants to get the room energized. It’s the first time I’ve done these chants (staples like I believe that we will win, or Free, free, Palestine) outside the context of an actual protest. The feeling really is powerful—rather than chanting from a place of jagged anger in an outside world where empathy is not a given, to be in a room where we all hold broadly aligned values affirming that we stand with each other.

I came into this conference curious about how committed, self-identifying socialists consider art to be part of their politics, but left with a larger question of how artists in turn can consider their work to be in service of liberation. One speaker calls it our collective duty to use our gifts to “make revolution irresistible.” I leave McCormick Center at once exhausted and nourished, hopeful that I can find a way to do my part from where I am.

About the author: Mrittika Ghosh (she/her) is a Bengali-American reader, journalist, and communications strategist currently based in Chicago. She holds a BA from Mount Holyoke College and an MA from the University of Chicago, where her focus was on migration and queerness in Francophone and South Asian contexts. She is a member of the Muña Art Writing Residency’s 2024 cohort, and has also been a bookseller, educator, and translator.