This article is part of a partnership between Sixty Inches from Center and Black Lunch Table (BLT) partnership, Crowdsourcing the Canon—an editorial series diving into the lives and practices of Black artists based in the Midwest, especially those whose Wikipedia pages lack sufficient citations.

Five years ago, Harriet Watson wasn’t pursuing a career as an artist. In 2020, like many of us, she was simply trying to navigate a global pandemic and a moment of civil unrest that defined a generation. But, as a biracial woman in conservative Indiana, she found herself thrust into the role of educator and activist amid a world suddenly hyper-focused on Blackness. Black people and people of color know it’s exhausting, being forced to explain and defend your identity under a relentless barrage of questions, both in good faith and bad. Yet, Black people in white spaces often find themselves assuming this role—whether they want to or not.

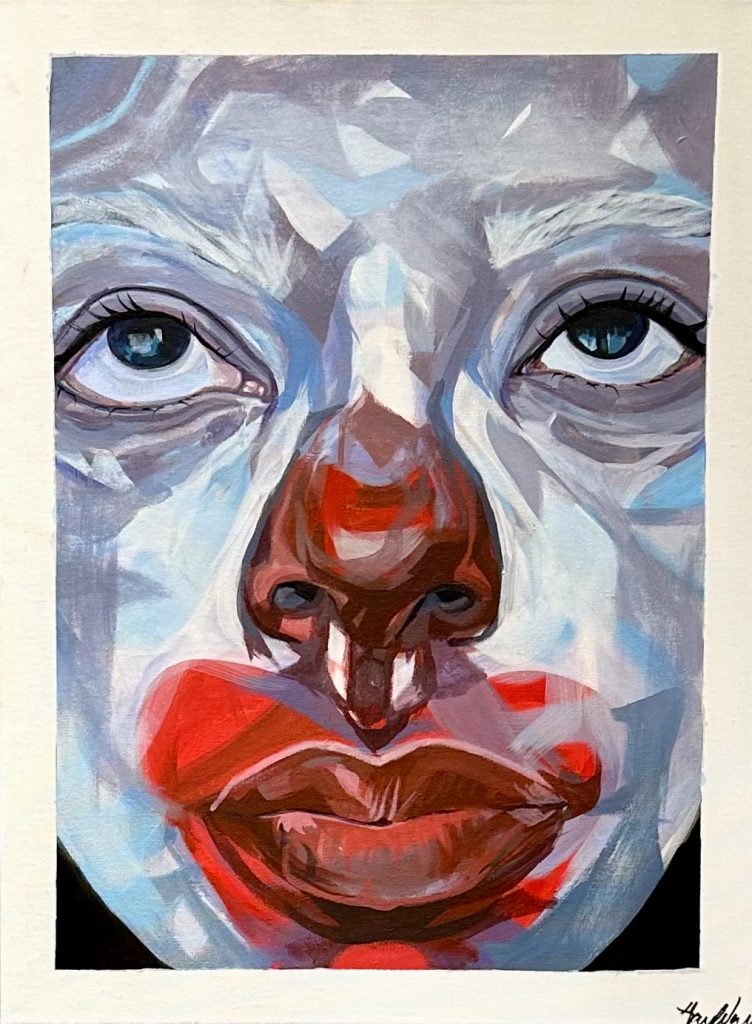

The self-portrait Fool’s Placation (2022) was her response to that moment and the external pressures placed upon her. This small acrylic painting is deceptively simple: a close-up of a blue-hued face with white-rimmed eyes gazing skyward. The mouth and nose are smeared red, the lips tightly pursed. It feels melancholic as if capturing the moment just after the show—the mirthful mask slipping to reveal the exhausted performer beneath. The clown isn’t laughing and neither are we.

For some people, there’s comfort in having an identity that’s easily understood. Harriet Watson is a multimedia artist living and working in Indianapolis, Indiana. Drawing from her personal experience, she has used figuration and portraiture to process the emotional weight of her experience with Blackness in the Midwest. But at the same time, an identity painted with broad strokes can be restricting, limiting, and incomplete. A mostly self-taught artist and part-time bartender Harriet Watson is biracial, adopted, and was raised by a white family in the very white very conservative community of Greencastle, Indiana. Over six years she attended Ohio Wesleyan, IUPUI, and IU Bloomington where she dabbled in art before ultimately attaining her BA in psychology. Her background, in her own words, is “complicated”.

With interest in Black art at an all-time high, it’s an exciting time for Black creatives in Indianapolis. The Midwest populace is more willing to engage with art, as evidenced by the commercial art opportunities, art fairs, murals, and galleries popping up all around the city. For the past few years, Harriet has been able to ride that wave successfully. Whether it’s her contribution to The Eighteen Collective’s Black Lives Matter mural located on the historic Indiana Avenue in Indianapolis (she painted the A in ‘Matters’) or her three years of successful showings at the BUTTER art fair, if you live in or around Indianapolis, you’ve likely seen her work. We first connected about two years ago, in the midst of her burgeoning art career. But, by the time Harriett and I sat down for a formal studio visit on a sunny February day she was already a few iterations into her brief career, and on the cusp of a new path entirely.

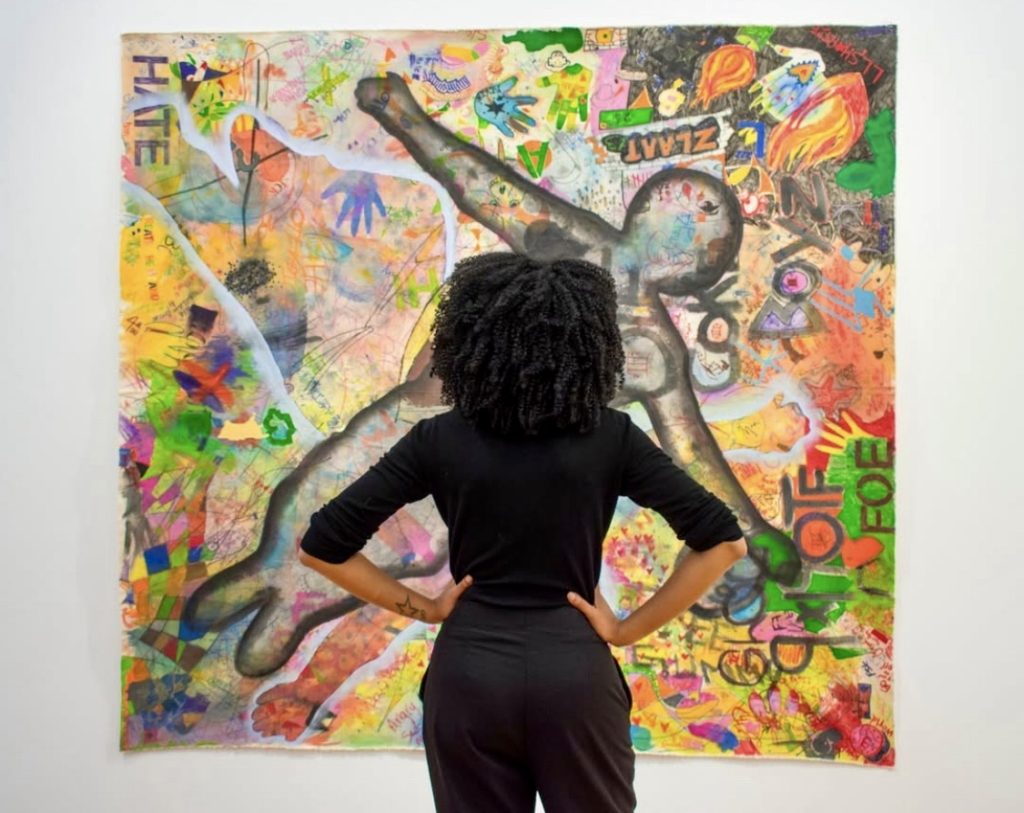

The first time I encountered Harriet’s artwork was in 2022. Her piece Welcome (Black Faces in White Spaces) was a part of the exhibition We. The Culture, a group show featuring works by The Eighteen Art Collective at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. In a contemporaneous review, I described the artwork as, “a digital image that depicts a group of people who appear to greet the viewer in front of a Neoclassical structure that resembles a government building. On the ground, a word in large letters reads “welcome.” Some members of the crowd hold white masks with simple smiley faces drawn on them. The faces of the crowd create an expectation as if they are viewing us and waiting for us to perform, it’s unsettling and concerning but you’re not sure why.”

From an early age, race shaped Harriet’s experience growing up in Indiana. As one of the few brown children in her community, she often found herself at the center of conversations about identity. In her art, she draws on her experience as a biracial person when it’s relevant. Yet, when I asked her about the term ‘Black art’ during our studio visit, she bristled, “If you’re Black and making art, you make Black Art,” she said matter-of-factly. In her work, you can tell she’s straining against societal expectations associated with race. Her subjects represent the surreal and often alienating experience of being Black, even so, she doesn’t necessarily identify as a maker of Black Art. She says, “People try to put you in a box. I’m really tired of being put in a box by society.” At this point in her career, she’s tired of the influence of the “societal construct of race” on her artwork.

When she first started making art it was a coping mechanism and outlet. She describes the painting of Fools Placation in 2022 as “cathartic” and a way to express what it felt like to be tokenized by the people in her community. But after exploring that subject for five years, it feels limiting and she’s ready to move on. “I’m done overanalyzing,” she says with a laugh. So for this next phase of her career, she wants to relax, have fun, and enjoy the practice of creating art again. What that requires is shedding identity politics and focusing on making and exploration. As our conversation progresses, she talks me through her current inspiration: abstract collages.

In 2024, Harriet debuted her first collection of abstract collages in a solo show at the Harrison Art Center. Titled Studio Notations, the series of about twenty works explores form, flow, and color through layered magazine pages and acrylic paint. These small yet dynamic pieces mark a striking departure from her previous figurative work. Each one is an explosion of color and texture, featuring no definite figures or forms other than what’s clipped from the pages of Vogue. These pieces are less about content, and more about her joy in the material, in dragging acrylic paint across magazine pages. Each piece is unique and vibrant; they’re exploratory, messy, and almost sensual.

“This is the only place I can do whatever I want,” she says of her studio, leafing through her collection of magazine clippings and paint swatches. The sun-dappled room in her modest Indianapolis home is small but filled with her inspiration and artistic experimentation. We look at pages torn from magazines, old books, and her clay creations. She’s relaxed and happy discussing a work in progress, while casually rearranging magazine clippings on the blank canvas. It’s unhurried, undefined. But what’s clear is her joy in the process, the discovery inherent in making art. She’s still exploring emotions, but less directly, less literally. At this moment she’s having fun. Abstraction is a powerful device, the indirect nature of the style demands that the viewer slow down and engage with the work to uncover its meaning. By moving into abstraction, in a way, she’s distancing her identity from her work, which is exactly what she wants. After being so emotionally raw and open, she wants to create work that “people can’t easily consume”.

As Harriet enters this next phase, she’s searching for balance—between personal expression, creating art people enjoy, and making work that excites her. As a self-taught artist, she acknowledges that technique is still an area for growth. Reflecting on her abstract pieces, she admits, ‘I’m not conceptually there yet,” But she’s eager to evolve by studying, experimenting, and refining her craft. She has a lot to say—and she wants to keep learning so she can say even more. But right now, she’s just following her intuition. “Every day I feel like I know myself better through my art.” She’s enjoying the process of shaping her ideas.

Black Lunch Table (BLT) is a radical archiving project. Their mission is to build a more complete understanding of cultural history by illuminating the stories of Black people and our shared stake in the world. They envision a future in which all of our histories are recorded and valued.

About the author: Jen Torwudzo-Stroh is an arts and culture professional and freelance writer based in Chicago, IL.

About the photographer: Cultural worker, imagist, and artist, Seed Lynn, submits remembrance as a liberatory practice. Whether sensually, technically, or artfully applied, Lynn meets the lens as an altered state through which listening and witnessing make voice meaningful. This state invades his work, frames subjects honestly, and in turn, shapes spaces where stories find students. Lynn’s own studies concern how we remember ourselves, how that memory is imaged, and how remembrance itself, in the face of oppression, is as radical an act as it is a work of art.