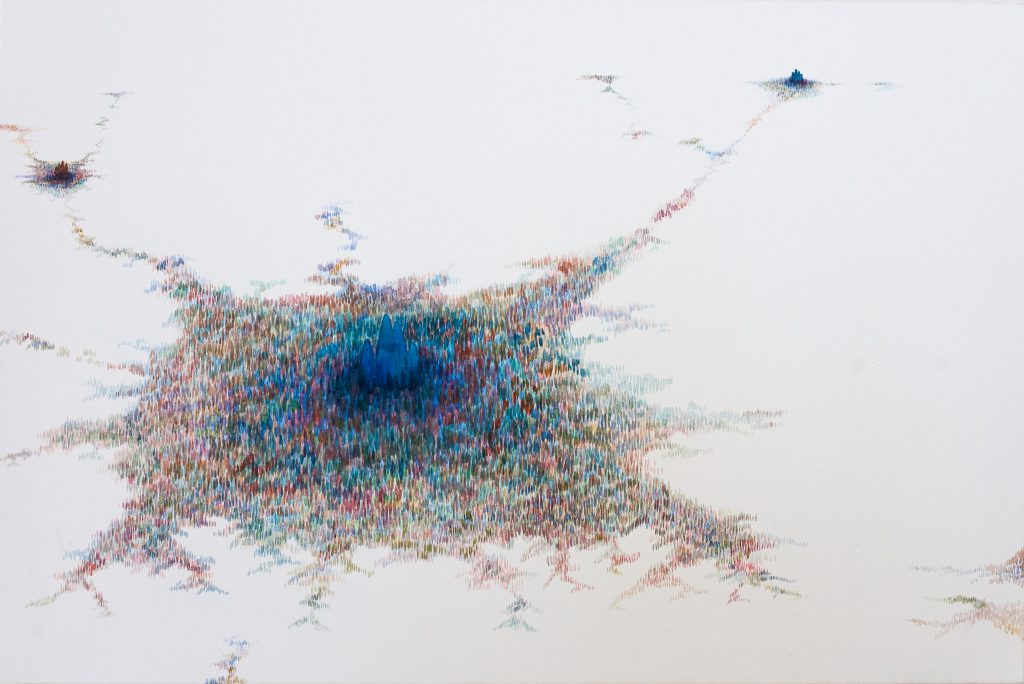

When talking to artist Preetika Rajgariah about how she arrived at her most recent body of work, I was struck by how a lexicon of movement naturally developed. She spoke about the strategies her family used to recreate the feel, warmth, and comfort of a home that was thousands of miles and oceans away after they settled in the city of Houston. She talked about how travel and relocation punctuated significant shifts in her work. She told me how one of her most commercially successful bodies of work addresses concepts of migration and accumulation but also whispers to how, aesthetically, macro perspectives mimic the micro and cellular.

But while motion might be one of the most immediately legible themes that one can draw out of her work, it is stillness that has actually allowed her practice to move forward in substantial and illuminating ways. Having discernment around what advice, suggestions, constructive criticisms are valid and useful and which ones counter her progression has allowed her work to bloom in ways that disrupt her original understandings of what art can be and what she ever thought she was capable of. What started off as a practice focused on large, heroic hyperrealism paintings has rapidly evolved into something far more abstract–aesthetically and conceptually–allowing space for her full self to breathe.

As she starts to count down the days leading up to a summer full of residencies, travel, and a slow return to Houston, Preetika and I spoke about the experiences and ideas that she will now take home with her. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Tempestt Hazel: When does it all start for you—this idea of being a studio artist and having a studio practice?

Preetika Rajgariah: That started a little later for me. Just being an artist as a profession was not why I went to college—I went for pre-med. I was starting my junior year and I didn’t even know that a person could be an artist as a career. I had very limited knowledge as far as what I was being exposed to but also when it comes to what I compartmentalized my life into. I was [split between] hobby and career. Art was my favorite hobby and that’s all it ever was. So, when I got to college I was able to fit a design class into my schedule. At that point I realized wait! People are art majors here?

I loved to make, I was always making art and I was a talented kid growing up. But when one of my professors asked if I’d ever considered art as a major or minor and I was like, “That’s a thing?” I didn’t even know. So, I switched majors and graduated with my BFA, fitting an entirely new major into my remaining two years.

And, honestly, I’m very appreciative of the people I got to work with, but at the same time I didn’t get a very deep, full BFA education at that point. I left a painting program not knowing who Kerry James Marshall is, or Barkley Hendricks—a lot of painters of color. I was very painting heavy and I was doing portraits. I look back and think, “Wow! I got an incomplete education!”

TH: Do you think you would have gotten that somewhere else? Would you have been taught about Kerry James Marshall or Barkley Hendricks at another school?

PR: I think if I went to an art school I would have. I went to a liberal arts school—really small, 2,500 students total, no graduate program. I think if I went to University of Texas or here [in Champaign-Urbana] with more students in the class, more faculty, more diversity…

So, I left not really knowing what it meant to be a practicing artist. My parents, of course, were like, “What is our daughter going to do with an art degree? She’s going to be a teacher! That’s what she’s got to do.” So, then I got a K-12 teaching certification. I got fully certified to be an art teacher because that’s the only thing I thought I could do with my degree. I feel like I was sheltered for a really long time—not only as a child in a very different way but also in my art career. I was in a very specific bubble.

It took a while for me to realize I didn’t like teaching K-12. Also, I didn’t make [art] for those two years and I became depressed. I also got married. My priorities were different, my life was different.

After quitting teaching I realized I wanted—although this sounds very selfish, it’s the truth—and I think artists or people who want to teach in general should be aware of this [when you feel it]…I wasn’t interested in putting my energy into teaching students and I wasn’t trying to make the next generation of artists. I realized that I wanted to put that energy into myself as an artist. So, I quit teaching and I immediately got into the summer residency at the School of Visual Arts. I got into this program and showed up not knowing what the fuck I was doing. It was a summer in New York surrounded by different levels of artists. This was in 2010.

But to answer your question, starting at this residency is when I was like, “Okay…this is what I want to do. And I have no ideas how to do it or what to make…” But at that point I had come into the residency with a very specific idea of what art was. And to me it was canvas and paint. So I got to New York, bought huge rolls of canvas and tubes of paint—I was so excited. Then, I had studio visits early on and everyone was questioning what I was doing and why I was using the medium [of paint]. Or why I was working at a giant scale. And I didn’t even know. I thought that was what you were supposed to do!

Then I thought, “You know what? I’m going to ditch all of that and think about, logistically, an easier medium to transport.” I was living in Houston and this residency was in New York—and whatever I made had to transport back [to Houston]. So I decided to do watercolor—abstract watercolor paintings. And for the first time, I started to think about where I come from. It was the first time that I thought about reflecting on my own life because [up to that point] I didn’t quite know what I was making about and I didn’t know anything other than my own story. So I let everything go and started thinking about people. And being in India.

Immediately when I think about my narrative my mind goes to India really directly, which is really strange because I’m not there regularly. I was born there and raised there for a few years as a baby and small child, and my family goes back every few years. Even so, it’s such a big presence in my upbringing and the way my parents tried to recreate India in America.

So, again, I started thinking about people and how many people are in India. I also started thinking about all these people in New York City and how it felt like being in India—all these different languages, all these people, and it was hot as fuck in the summertime. How people walk everywhere. It was everything—and that’s when I started making these layered paintings of bodies. And that’s when I started considering myself as a real, working artist because I became really connected with myself and my inspiration. I was doing these formal things but also I started painting figures that had a real narrative and a connection.

That body of work spanned five years. And throughout that time there was life stuff that happened. When I finally got to graduate school, I had a rude awakening and realized how far behind my knowledge of art was because of the knowledge I didn’t get in undergrad. For me, being an artist was such a natural thing—but I needed to catch up in the academy.

TH: I want to back up a little bit to when you realized that you didn’t want to teach and you wanted to turn your attention to your own work. Was there any guilt in that for you—realizing that teaching might not be one of your goals?

PR: I recognized that it was a selfish feeling.

TH: That’s an interesting word to use. Where does that feeling of obligation come from? Is it because that’s what you’ve been told is the logical path? Here, in Chicago, there are so many schools and programs and there are so many artists who teach—K-12 or in higher education. Although I have so much respect for teachers, I, myself, have never ever wanted to be in the classroom like that—so what you said really resonates and at the same time it feels against the grain. So it’s interesting to me that you would think of it as a selfish thing, when it’s maybe simply you identifying the best place to channel your energy at this moment in time.

PR: I think because I feel teachers are really generous people.

TH: Yes, for sure!

PR: They are the most under-appreciated people—in this country especially. Abroad it’s sometimes a different story, but here teachers are not respected while they put so much of themselves into the students. I was doing that and realized that because I was putting all of my energy into the kids, my practice was non-existent and I was becoming very depressed. I knew something had to change. I wasn’t doing anyone any favors—the kids or to myself. I got a lot of pressure with each of the decisions that I made with my life—from my mom specifically. She was concerned with how I would make a salary and why I would let teaching and, the stability that comes with it, go. So, I tried [several different jobs].

TH: Do you feel resolved now and good in your decision to go in the direction you’re going now?

PR: Yea, I really do. I realized I wasn’t the person who needed that kind of source of income. I can’t do the 9 to 5—I tried some gallery and art space jobs and I realized that it’s not for me either. But I’m happy that I like the hustle—as annoying as it is sometimes, it’s really rewarding too. I’ve come to live that way and that’s just how I roll—I’m fine with that.

TH: That’s a really great realization to have.

PR: Lots of learning.

TH: And a lot of listening to yourself, too, which I think is so important for longevity and happiness—and all of the things that we want in life. I want to hear more about when you realized that your work wasn’t doing what you wanted it to do, or you wanted it to do more, and you figured out that it was a way to understand yourself better.

PR: This makes me think of my surroundings at the time. I had just quit teaching and suddenly went into the artist residency. It was a mix of artists—some established, some mid-career—a range. And I was static for the first two weeks that I was there. I get insecure in places like that [because it seems like] everyone knew what they were doing there. Everyone had their practice at a time when I didn’t even know what an artistic practice was made up of. If I was to go into a residency now, I would know my materials, I would have a sense of that. At the time, I took cues from other people and had a lot of conversation. And eventually I sat with myself and thought about what made me different in that space.

It’s funny; I say that India came up then for the first time but I don’t give enough credit to my undergrad self—because it was so rushed—but my thesis for undergrad was oil paintings of myself in the nude done in classical postures from Hindu mythology, then collaged with my mother’s clothing. So, I started working with textile and the body ten years ago—and I got no real feedback one way or the other from my professors at the time. I remember thinking that these paintings represented me being a modern Indian woman because I’m naked in these paintings, in traditional poses and I’m collaging my mother’s fabric onto these canvases—which in a sense is exactly…

TH: …what you’re doing now.

PR: Literally, it took me to get here in order to have that hindsight. Really, this is what I’ve always been interested in. This is what I’ve always made work about, which makes me feel like I’m on the right path.

TH: If you were doing figurative work, what made you go to the other end of the spectrum of abstract painting? Even when it evokes a sense of the birds eye view of the collective, and there’s an individual figure in there somewhere—its extremely simplified and abstracted.

PR: I think there are a few reasons. Part of it is my nature as a maker—I’m a really impatient person…

TH: You wouldn’t know it from these pieces. There’s a lot of accumulation there!

PR: I know! Accumulation and repetition are my go-tos visually. But I’m so impatient and I wasn’t having fun [with the work I was doing before]. I was doing photorealistic portraits and was having a hard time stepping away from that. Attention to detail was my nemesis. I lost interest in that and it felt forced and limiting. It wasn’t conveying what I wanted it to—the material wasn’t right.

TH: Five years is a long time to spend in this work—doing watercolors. What made you break into the next body of work?

PR: I knew that chapter of work was pretty much done for me. I was ready to move on and challenge myself—and that’s when I applied to grad school. I wanted to get criticality [around my work]. During those five years I wasn’t getting any feedback—it was just me making and being in group shows here and there. I was selling a lot of the work and sold almost all of the paintings I ever made. I was ready to have criticality.

[With the next body of work], I started thinking about India again. I had just gotten back from my cousin’s wedding in 2011. I had just gotten divorced when I left Houston for [University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign]. So, I carried a lot of baggage—I always carry a lot of baggage around India, but specifically around being a divorced Indian woman—my family was broken at the time and still kind of is.

But I ended up here, in the Midwest, alone, which was great. I immediately noticed that it was a super different feel in Urbana-Champaign than in Houston. Making here was different than making in Houston. Going to the grocery store was different. I was the only person of color in my program—except one other third-year.

When I first came to grad school I was talking about my early paintings because it’s what I entered into school with and I went back to the place that inspires me the most. I realized that there was content in my story of being different. And I don’t get to hear my story, hardly ever—there’s power in that. I realized this is something worth sharing.

Ever since I got more into textile, which has been an ongoing interest of mine in non-art spaces and a way to connect with the women in my family, I have done a lot of unpacking over my relationship with my mother and connecting with that upbringing.

TH: To fast forward into the textile work—I find the evolution and how you talk about where you are with you work, and how everything keeps coming back full circle so interesting. For instance, I get a similar feel from your water colors as I do from your thesis installation of the Aunties. It goes from the birds eye view to the zoomed in view. There’s a way in which space is happening in your work—whether psychologically or conceptually. You’re moving into the life-sized and up close realm whereas before things were super small and distant. That could be interpreted as a metaphor for all kinds of things but I want to know how you think about that. How, when, and why your closeness or distance from these bodies changes…

PR: The idea to make [the Aunties] is a direct relation to my old [watercolor] paintings. I’ve always been interested in transparency, layering, revealing, concealing—so visually I was interested in that but I was definitely interested in how to make a three dimensional version of the painting. It was an interesting material challenge. They started off really small and looking like I recreated one of the temples at my mom’s house like in a lot of Eastern households. Hindu households usually have a proper temple with little idols and figures. I started off making hand-sized, three-dimensional things. I’d been working on the wall for so long. My whole concept of art had been on the wall. But now I really wanted to try anything and everything I could try. I wanted to experiment and see how far I could go. What does me making sculptures look like? I went through a period of flags—2-D but off the wall—banners and flags…

Once [the Aunties] were all little and they looked like a shrine or temple, I wondered if I could make them my size. I started creating my own tribe, basically. I loved creating and thinking about these women figures. Because of the material I was using, they were definitely gendered. I began creating the Aunties I would have wanted to grow up with and didn’t. The Soft Bodies collection as a whole represented a lot to me but first and foremost it was fun. I pay attention to when I’m having a good time at the studio.

TH: That makes sense. So, the Aunties seem to have their own evolution within your practice, but then there are these other works that happen throughout this time—like the video. I’m curious about how you re-introduced yourself into your work at this point, literally. What compelled you to do that?

PR: Honestly, it was me wanting to challenge myself in grad school. There was a performance class offered at UIUC—and I can be a performer sometimes. I have this [performative] part of my personality and it intrigued me. Then, I was being introduced to a lot of performance artists. Through them I realized I had a lot of ideas about the way I could use my body in my work because, again, my work is highly inspired by my narrative. I felt it was important to use my body as the vehicle for some of the conversations I wanted to start having. I have a lot of ideas, and I wanted to expand on that. But it’s super scary—like in the way that going from 2-D to 3-D was a huge leap for me—3-D to performance is another huge, seemingly insurmountable mountain.

TH: With your work—especially the Aunties—I love the titles. They’re sometimes so humorous. But also, there are other works I’ve seen by other artists where this accumulation of figures that are anonymous, life-sized, and hidden is used to evoke a certain kind of emotion that is definitely not humor. They’re much more moody—but how you’re doing it, there’s a way in which you disrupt the drama and moodiness that a presentation like this usually creates. Or the serious topics that are usually being tackled through approaches like this.

Once I read the titles, I felt like you were saying, “Don’t take this all so seriously.” But also, I had to check my assumptions for a second because I realized that maybe I was interpreting this as weighty simply because of the way this work is sometimes understood within a US context, which is very contested and contentious. It’s not just about the work or the work being in this art space. It’s not just about the fact that the work is beautiful and impactful. But it’s also about the realities that we live in, which are imposed upon the work. A viewer’s thoughts might wander to how this work speaks to xenophobia’s presence the country that we live in or contemporary conversations around migration and immigration—things along those lines. So, I’m curious since you were recently in this space of critique in grad school, have you noticed things that come up regularly or are imposed upon your work? Do people hit the mark sometimes, or are there unintentional interpretations of the work you do because of the era in which you’re doing it?

PR: When I first came into the program there were a lot of thoughts being projected on the paintings of masses [of people] I was doing because they have loaded titles—like one of them is called The March. At the time, things were happening globally with refugees, human movement, migrations, and crisis associated with those events was projected onto my work. That’s not necessarily what I was thinking when I made the work.

With the Aunties specifically, when I first started making them I was using darker saris because that’s what I was using to do my material studies—they were navy blue, brown, black-looking. Dark, concealed bodies in a space got a very funerary response. That wasn’t what I was going for! So, I thought to myself, “I’ve got to go rainbow! I need to queer this shit up!” I wanted to make things I was enjoying. And also, in India, the funeral colors are white, not black so…

TH: Right—this is the impact of context…

PR: There is also the hijab read, and the burka read. And with that I struggle—I’m a South Asian woman and not a Muslim woman. When I think about people in India, a lot of times, culturally, women will take their sash and wrap it around themselves for a number of reasons—[but it can be interpreted as Muslim].

I also get critique about the facelessness of them and to that I explain that it’s not about specifics or portraiture. They are embodiments—recreated nostalgia. They are pieces of memory that create a form.

Sometimes people put a negative spin on the soft bodies—more submissive or women being contained. But I see it as containment of culture, or how, at times, I’ve felt constrained, or conversely, supported by my culture. I have a [challenging] relationship with India and my background. I think it comes out in the bodies—they are kind of confined and bound but also adorned and independent. But there’s a lot that’s gone into them. And how they are arranged in space impacts the reading and the feel. I haven’t had the space to play with them [as much as I’d like to].

With the video “How about now?”, I get great feedback from non-art people, for instance, museum guards. Or the parents of other students [at UIUC]. Another South Asian graphic design artist who graduated with me, her parents came from India [to the MFA show]. Her mother came up to me and said the video resonated with her and asked what the piece was about. Then I asked her, “Why don’t you tell me what you think it is about, Auntie?” Auntie or Uncle are terms of respect and endearment. [She explained that] she thought it was about the violence that continues after a wedding, into a marriage. And India right now—well for a long time, really—but definitely recently has been getting negative press about how women are treated. It’s true and I’m glad that women are starting to tell their stories and be able to bring attention to this. But she brought that onto the work.

For me, the piece is about marriage—something I’ve been through. It’s about my personal experience with feeling good enough or successful enough [through marriage]. But because of the materials and the way that I handle the materials in this work and others, I’ve gotten interpretations of violence before—the burning, tearing, bleaching—these are violent acts.

TH: You mean in the textile works—the wall pieces?

PR: That’s right. Her interpretation really touched me, and made me want to say, “I hope you’re okay or I hope the people that you know are okay…” I felt like we had a conversation without saying much. It was a very interesting exchange. It made me feel like the show was a success. When people can personally connect with my work, I find that to be the greatest thing.

TH: I find it fascinating and so important that the guards, another student’s family—that those are the people who respond most. That’s not usually your intended audience when you’re pursuing your MFA. Or that’s not who you’re expecting a response from. But when it speaks to them—and also when work speaks to children, or family—the other people moving around the work—when it resonates with them you realize that they are actually the tough audience. And it resonating with them is a different kind of success and understanding.

PR: I completely agree! As I’ve started feeling empowered in my voice and like I have something substantial to say though my work, I’ve started to understand that these are the people I hope to connect with. I’ve also made it a side-mission of mine to increase art appreciation in South Asian culture because it’s pretty low. I want to go back to Houston to work within the huge Southeast Asian community there.

TH: I really love the portraits that you do of yourself. They feel like a middle ground of your work—because they reveal things about your own relationship to India, but then also what it’s like to be Indian in this country. But then, too, it speaks to something you said earlier about needing to queer things up. These photos feel like the intersection of all of the different things you’re thinking about. I’m curious about how these photos function for you.

PR: It’s funny, I always forget about those!

TH: Really?! I find them to be jarring and beautiful.

PR: For me, they function as a sketchbook almost, or a precursor to performances. They all came from performances. I almost see them as an in-process place. I really enjoy them.

TH: Some of the things that you’ve said about the work—the oscillation between being confined but containing culture. Or the concept of wrapping something and the different ways that can be interpreted. It’s interesting that you see them as a sketch because I see them as a collision of several different things and a connection point between all of the ideas you’re working with. It’s you, and it’s pointing to the Aunties, it’s pointing to the early work with your body and your mother’s textiles. They hold a specific place in the body of your work, in my eyes.

PR: I have a hard time seeing photography as the final product of my art. Maybe it’s because it’s so related to my side hustle. Maybe it’s because it’s too quick of a process for me. I’ve never thought of it as a place where I’m connecting all of these dots.

TH: Speaking of connecting dots, I find that the titling for your pieces are, in a way, excerpts or give beginning reference to your writings. The fabric wall pieces have titles that are cryptic and foreshadowing. The titles beg the question, “What’s the story there?” What I really like is how you’re able to mix the presentation of complete joy and humor with weighty commentary and discomfort. I think it’s very timely and I think art is at its best when there’s happiness and joy, but it also makes you somewhat uncomfortable. We’re in a time when we don’t know whether to laugh or throw something.

PR: We have to laugh to get past the atrocities—it’s why people make memes out of everything! But the writings are little snapshots to my memory. As people have read them, I’ve gotten a lot of great feedback because the writing offers insight and helps people connect. The stories are very honest and I think of them as comedy—a lot of my sarcasm and sense of humor comes out in them. They are short vignettes.

TH: The writings feel like title expansions to me. And the humor piece—where you bring in humor is important and—as I keep saying—very timely. All of the things in your big box of references and strategies and how you’re approaching and thinking about your work, humor plays a very important role. And that, for me, is what sets it apart from other work that is visually in conversation with yours, but the humor piece adds something different and cuts a tension that can happen in a quick read of your work. You allow for that tension to be easily broken if people dig a little deeper.

Also, I like to think about how your work would operate in different spaces with different audiences—especially since you’re working in so many different forms.

PR: I’m excited to take my work back to Houston—a big city with many diverse audiences. I look forward to re-entering the arts community as a more critically-positioned artist, which is something I was scared to do before with my paintings. This is why they had serious titles and were very subtle in that way. I think I can take charge of my work a little more now and address some topics that I am passionate about.

__

Featured Image: Installation view of Preetika Rajgariah’s MFA thesis installation. In a gallery setting, there are three distinct works. To the left is a wall-sized still from “How About Now?”, in the center there is a cluster of seven Aunties, and to the right, directly on the wall, there is a floor-t0-ceiling wall painting of Preetika’s silhouette in red, with large, red painted bindi’s outlining where her face would be.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including Cecil McDonald, Jr.’s In the Company of Black published by Candor Arts. You can also read her writing in the upcoming Art AIDS America catalogue for Chicago and the online journal Exhibitions on the Cusp by Tremaine Foundation. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including Cecil McDonald, Jr.’s In the Company of Black published by Candor Arts. You can also read her writing in the upcoming Art AIDS America catalogue for Chicago and the online journal Exhibitions on the Cusp by Tremaine Foundation. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com.