you for this is just blackness

you for this is just blackness

you for this is just blackness

G.L. – I don’t know that I can write his name here for fear of legal reprisal – haunts billboards from Chicago to Michigan (at least), his chin, the chiseled basin of his brickhead split open by bleached, saliva-polished teeth: sue the bastard who did this to you, we’ll make a buck, you’ll make a buck. On the CTA platform, I close my eyes, inhale and find my center in all the noise of rush hour while wind tunnels and pours dank air through the crowd. I do this for five minutes. I open my eyes. G.L.’s stupid face is waiting for me. I brought this up to my dad once, how unnerved I was by G.L.’s persistence, and he told me that a friend of his once called the number on the billboard, and that the office was not in Chicago but somewhere in Arizona.

G.L.’s interstate visibility bothers me. Not because of him (though I harbor some suspicions about successful white men and their motivations), but an itch triggered by signage and its persistent occupation of my mental real estate. For example, my joyfriend and I drove to Michigan and Wisconsin this year, seeking quiet places where we could hold our hearts in our hands and soothe our electric nerves. I see billboards: some about life beginning at conception, a gentle reminder that anti-choice is a strong movement in this country; others with simpler adages next to simple illustrations: “Stressed? [White] Jesus will be balm.”

How? A balm for twenty-eight years of anxiety? Does Jesus have an ounce of weed and serious experience as a masseuse? Because my shoulders are tight and I can’t tell if I’m breathing anymore. Whether he could balm up those stigmata-laden palms and massage some of the existential anxiety out of my shoulders, I couldn’t say. But I remember these signs. I dwell on them. I dwell on G.L.

This year, I have not been haunted by him because I hadn’t been on the CTA since March, and neither had the friend I met on the street beneath the Fullerton red line station. I double-masked for when the novelty wore off and I got nervous about sickness again. A few feet from where we settled on the platform, facing the DePaul Art Museum’s brick wall, somebody coughed heavily and loudly, my friend edging away from them and a little toward me.

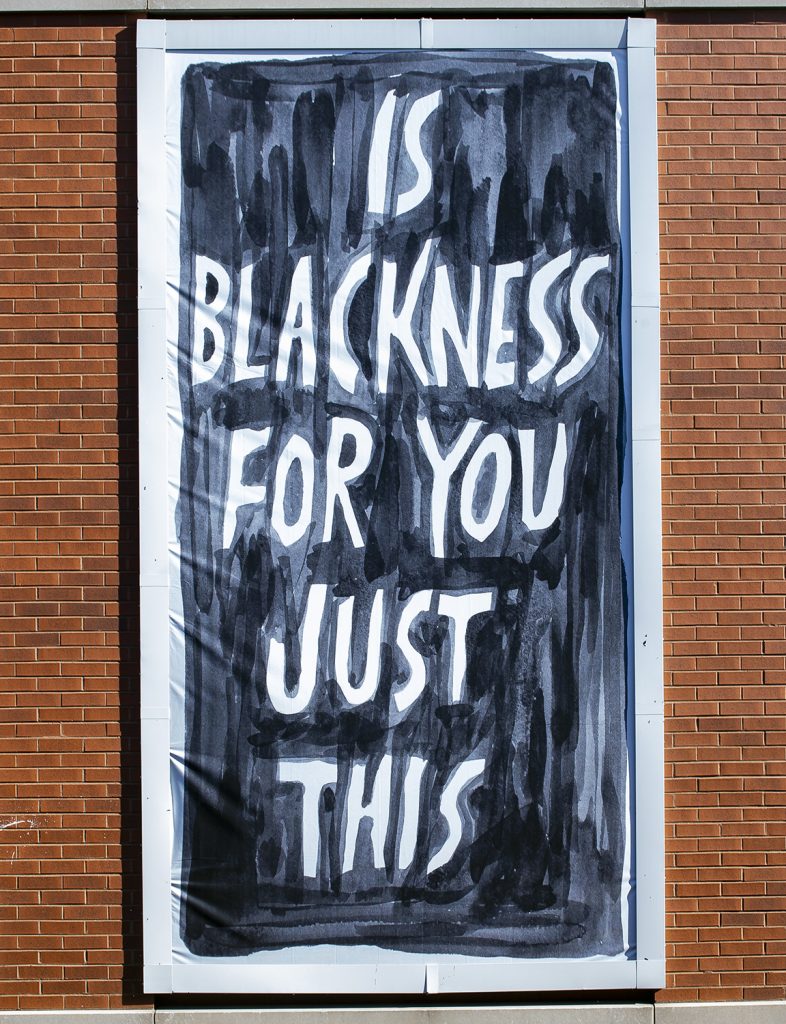

While we got reacquainted, the northbound train circulated in front of Ayanah Moor’s for you, four prints hanging on the building, each with the same ghostly words in the same curdling white on the same watery black backdrop, stretching maybe the height of one and a half people. Despite being latex strips periodically blocked by the train, they’re psychically firm. The words all capitals, repeated – “for,” “is,” “just,” “blackness,” “you,” “this,” – embed themselves into the walls and one’s mind in four arrangements, each just as vague as the last. Each banner rippled in the afterdraft of the train, open-ended questions: they resemble thought bubbles, koans about Blackness, about you, about where you are right now. The one furthest left, my friend told me, seemed belittling. I thought it felt mythic.

Moor has expressed interest in the way information is organized and what it reveals about people. In the link above, it’s a map of the most frequently searched terms on Pornhub by state. At the DePaul Art Museum, it’s how one organizes language for one’s self. In an aesthetic sense, for you’s simplicity and repetition resemble Glenn Ligon’s paintings, though if Ligon – not the same G.L. by the way – mutters to eternity, then Moor asks you to press your hands into this substantial moment and your substantial interior through these words hung momentously. She does not ask you (explicitly) to consider statistics of racist disparities or the brilliance and resilience of Black people in the face of genocide and disenfranchisement. But if you have those on hand, they’re good to remember.

In the context of the Fullerton stop, she expects us to come as we are: commuters, strangers. By declining to include narrative or quantitative information, an audience can only draw on our own histories and knowledge. In the cold, I rearrange emphasis and punctuation, decomposing and recomposing my intent, subaudible, pockets of air escaping my lungs in streams of bodiless words at the platform.

Moor’s (maybe) gracious ambiguity asks “Reflect. Perceive yourself and respond”: what is my relationship to Blackness? And which Blackness are we talking about? The American Blackness? The ambiguity gives enough reason to avoid being convinced of anything except my own complicity and a want for something else. American Blackness is just for you, Percy, just for you, G.L.; just for you, DePaul; just for us, white people.

After the murder of George Floyd – and many, many other Black Americans – we saw uprisings and protests across the world, while on localized, academic scales we heard a chorus of BIPOC students from places like Loyola, SAIC, and DePaul reach out to pull apart the white arcade of microaggressions and macroaggressions inside institutions acclaiming their diversity. Enraged slogans became easy to come by: Defund CPD; Justice for Breonna; Decolonize Zhigaagoong. These stick in my mind as well, far more so than the billboards…though the position they occupy is different.

Billboards, advertisements are ambient, presumed, pervasive. We just see them everywhere and I don’t welcome the rote mental space they occupy, while the persistence of protest signage is very much appreciated, an indication that the wrong and unjust (is this the just she means?) is in the process of being redressed: someone will be held accountable and something will change because finally things are hot enough to. Likewise, they gain their power from the repetition of a crowd. Protest signs have an explicit purpose, explicit messaging—not unlike billboards, though these signs are exclusively political and unseen outside protests. Certainly not on the train or bus.

Moor’s for you lives in the Venn diagram of protest signs and billboards, utilizing both the interrogative nature of the former and the ambient worminess/location of the latter. The questions posed here are for you—that’s you, specifically—to consider until you’ve arrived somewhere. It’s a passing thought, one you pass enough that someday it takes on more depth, a question that doesn’t judge you for your answer. You don’t have to think about it, but what if you did? I didn’t have to think about Masseuse-Highway-Jesus, but then I did for forty miles.

Indulge me. What if the space G.L. took up were occupied by Ayanah Moor’s suggestions permanently? What if for you occupied the adverts of the nation, posted up every forty miles of highway, every two stops on the CTA? I wonder about how integrated these words would be if truck drivers and wanderers and commuters glanced up between pine trees and between endless scrolls, saw these simple words as a simple invitation? What if we played with these words until we saw something new arise in ourselves, without any pressure to be right or wrong about these words, removed from an ulterior politics? What if it was printed all along the Jackson tunnel between Blue and Red lines downtown, or where Green meets Pink? Or here, on Fullerton, where Red again meets Brown?

this blackness is just for you

this blackness is just, for you

this blackness is just, for you

this blackness: is just for you

Though, it is Lincoln Park, where white people meet white people. My friend and I, white people, met here. for you is not a balm or salve for white people’s supremacist tendencies and defense mechanisms. It’s a demand for specificity of definitions and goals in ways that the audience deems fair and compassionate to themselves. You’re expected to expand with them.

Indulge me. If for you were posted across the nation, a question for you and only you: Would Black lives finally matter?

I recognize my own naivete regarding the power of questions and language, though the thought arrives from a place of stillness that for you requests. When I used to sit on the train, in motion but not, I found quiet. Now, I think that introspection—in a culture which willfully distracts away from discomfort and engages with pain as static disengaged from—is maybe the most tiny step towards collective engagement.

Finding stillness on the train—the literal transition from the minute and grandiose nightmares of capitalism to the comfort of our nesting—we have an opportunity to find a bigger world. A world with more choices of how you relate to each of those tiny expansions. for you is filled with the potential of moment-to-moment revelation and choice and infirmity, like pressing hands into ice until a gradual silhouette has formed in it and you understand the way your hands can help decide the shape of a glacier, dense, solid, seeming to never end. Look to your right, then your left: you see imprints in the ice. The shape of these hands is unfamiliar.

When my friend and I leave the station, adverts on the way down feature racially ambiguous, light-skinned people, all talking on the phone wearing Gap cardigans and beaming with teeth that are brighter, whiter, straighter than my own; each ad details a phone plan, the most basic cost dog-eared by an asterisk dragging your vision down to ant-sized legalese which I could read if I wanted to, but I don’t. The CTA blows past the collective for you banners, again and again, each time sending a different shiver across that skin.

for this blackness you just is

for this blackness, you just is

for this blackness, you just is

for this blackness, you just is

Ayanah Moor’s installation for you is on view at the DePaul Art Museum until December 28th. More info is available at the museum’s website.

Featured Image: for you by Ayanah Moor, at the DePaul Art Museum. Four tall latex prints, each with white text against a watery black background and a white frame, hung next to each other on a brick wall. To the left is the tail end of an outgoing train. Beneath the prints are a concrete barrier between the track and open air. Photo by Mark Blanchard.

Persephone Jones is a writer, theater maker, and visual artist whose work focuses on the interaction between the Waking and the Dreaming. They discover threshold worlds occupied by symbols given flesh, flesh turned into ideas, many bodies condensed into one and vice-versa. They’re the Associate Artistic Director at the Prop Thtr. You can find more about them here and here.