Image: An illustrated portrait of Erin Sharkey and Zoe Hollomon standing in front of a body of water with a stretch of open land seen in the distance. To the left a bright red farmhouse and another building can be seen in the distance, surrounded by trees under a blue sky with light cloud coverage. Illustration by Kiki Lechuga-Dupont.

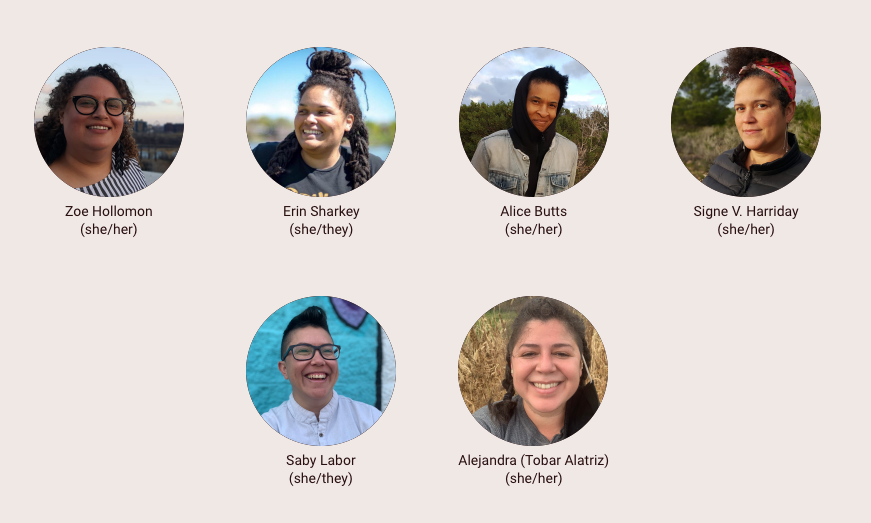

When I sat down to talk with Zoe Hollomon and Erin Sharkey, a married couple in love and life, the sun was blazing and the weather was still hot in Chicago. The days were slowly starting to get shorter and at that point the calendar was one of the only real signs that fall was on its way. The other sign was the pure joy that radiated from the computer screen as Zoe and Erin told me about when they would finally get to spend weeks on end at Rootsprings in Annandale, Minnesota, a 36-acre retreat center that they co-run on the unceded territory of the Dakota people. Fall 2021 would be the first time they would experience harvest season on those grounds, since February 2021 was when they and the other two married, lesbian couples of Rootsprings Cooperative reclaimed the land in the name of community, healing, revolution, and artistry.

To understand how these three couples, made up of artists, environmental organizers, and activists, acquired this ecologically vast and fertile site, you must first know the history. Prior to the members of Rootsprings Cooperative receiving the site, this Dakota land was known by some as The Fields at Wellsprings Farm. Before that, and since 1988, the land was occupied by the Franciscan Sisters of Little Falls who used it as a retreat space for the Franciscan community until it changed hands to private owners in 2014. In late 2015, a nonprofit organization called The Fields took over the management and operations of the retreat and the land, resulting in the renaming of it as The Fields at Wellsprings Farm.

The journey that led to the land being rechristened as The Fields at Rootsprings began with the social, political, and cultural jolts that shook us all in 2020, with one of the most galvanizing shifts happening with the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, where Zoe and Erin are currently based. In an effort to acknowledge the outcries for justice that were sounding loudly not only throughout the country but just hours away from them, the owners of Wellsprings Farm decided to begin conversations around transfer of ownership to local Black, Latinx, and Indigenous organizers as an act of reparations.

The space is now known as The Fields at Rootsprings. It is a site of healing and rejuvenation that centers queer and melanated artists, organizers, and healers in need of replenishment in a setting that caters to their values and also their dreams—dreams for themselves, their communities, and the Earth. The model that the six of them are creating is anchored in cooperative principles, reverence for the land, and the ancestral origins of people like them. Through Rootsprings, they are addressing the lack of spaces where freedom fighters can, if only briefly, remove their armor and focus on healing and nourishment. They are quite literally world-building towards an existence where the caretakers of the people are cared for and a life of subsistence is a distant memory.

As we enter more deeply into the winter months and sit at the edge of a transition into a new year, I am grateful for the chance to revisit Zoe and Erin’s words. The following conversation is a generous look into the endless depths of their work as individuals, as life partners, and as members of a cooperative that is sowing love seeds everywhere they go.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tempestt Hazel: How would you introduce yourself to someone who doesn’t know you?

Zoe Hollomon: I am a multi-racial Black, queer organizer and artist. I work with the Pesticide Action Network—I’m the statewide organizer for Minnesota, so I support several grassroots organizations around racial equity, local control of food systems, and environmental justice. We predominantly focus on industrial agriculture, which relies heavily on monocropping and pesticides use, and is the main type of agriculture in the state. The infrastructure that has made that so is very powerful economically and politically. I support coalition building and policy work to help transform our food system to one that’s more sustainable and equitable. I support farmers and rural communities most impacted by pesticide drift, soil or water contamination to have the tools and strategy to fight. Urban farmers, pollinator advocates, local food supporters, water protectors, many people and groups who see the shared risks of our current food system and are fighting too. I support organizations through campaigns or organizational development, or policy education. My organization does a lot of scientific research too, to help support that.

About two years ago I started organizing with farmers of color in the Midwest—mostly in Minnesota, but also in Wisconsin. Now, it seems like we’re growing to other states as well. We started bringing farmers together to talk about racial equity and what we want and deserve. With many of the baby boomers retiring farming, many are wondering who will be our food farmers? Farmers of color have been fighting to farm, but exploitation and oppression is what we’ve gotten. Most people of color have a legacy of growing for our families and communities and so we tend to do more sustainable farming and food production. That’s exactly the type of farming we need for food security, and to address the health, environmental and economic crises we’re seeing. It’s literally the future we need to support if we want to sustain life on this planet.

Erin and I did urban agriculture with young people and communities in Buffalo, New York, which was my entry into food justice work. It was a great way to use my academic background in urban and regional planning, also economic development as well as my passion and interest in community economic development and liberation organizing.

Midwest Farmers of Color was a group I was working with before I worked at Pesticide Action Network—their work is a big part of transforming our food system. I also support some groups that are doing well water testing, well water clinics, or working to find ways to expose how industrial agriculture is impacting people’s health and environments.

Then there’s work with other Black organizers as well. Erin and I have been a part of that in many ways since we moved here in 2012 and we helped form a group called Black Liberation and Abolitionist Cohort (BLAC) after George Floyd’s murder. I’ve been advocating on behalf of myself and other organizers of color who are doing so much but are rarely supported. We’re contracted by nonprofits who don’t pay us like employees. We end up not being supported with our healthcare, finances or taxes. There’s a lot to be done with local foundations and Black organizers to talk about how to build the ecosystem with support for those who are building and supporting the movement. I think groups like Black Visions among others are thinking systemically about how to make that happen and it’s really critical. I see that as an important point goal for Rootsprints, we really need support and healing for the Black organizing community.

Erin Sharkey: My mom is irritated because I don’t have one job, so it’s hard to tell her friends what I do. I apologize for what might seem like a laundry list! Zoe and I are married—we’ve been married fourteen years in October. She left that out, but it’s really important.

ZH: I left out so much of the personal things, too!

ES: There’s so much that she didn’t say, but we’ll get to that. Work is important—we’re workers! I’m a writer, cultural producer, and arts organizer. I’m an abolitionist and educator. I’m part of a cultural production collective called Free Black Dirt. For the past ten years or so we’ve been throwing the best parties in town and consulting with organizations that want to do programs in new and dynamic ways. We’ve been creating parades and puppet shows—things like that. Right now I’m editing an anthology called A Darker Wilderness with Milkweed Editions Press. I’m inviting Black writers to think about nature as a political space and the ways that Black folks have been in relationship with nature despite the ways that the state has aimed to disenfranchise us from nature. So each of the essays are connected to a piece from the archives. My contribution to the book is thinking about the way that urban places have natural rhythms, also thinking about Benjamin Banneker’s Farmer’s Almanac. And I may use the almanac as a form to think about our time in Buffalo.

So that’s part of what I do.

I’m also a film producer. I’ve been spending the summer producing a television show about Black-owned businesses and their particular challenges.

I’m also a teacher—a chronic adjunct teacher. But for seven years I’ve also been teaching with Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. I have the distinct privilege of bringing writing classes to our incarcerated loved ones and families. I teach 10-week or 15-week courses on writing about family, memoir, writing about nature—general intro into creative writing.

TH: What first got you into doing work with the land? Where did that desire and interest come from?

ES: I came from a family that camped every summer when I was growing up. I saw 48 states and all the provinces of Canada that touched the US. I got to sleep in the wild diversity of the biomes in the United States. I’ve always thought about nature as a way of marking time and how life is always teeming around us. Nature just keeps doing its work in the world.

Then, I had the serendipitous awesome experience of starting the farm project in New York, which started from a tiny project that I volunteered for—a job that really changed my life. Zoe and I were friends, and she was in grad school trying to think of a practical project to do. I asked her if she’d ever thought of a food-based project. Have you thought about a project where you could work with teenagers. And she thought that was crazy…

ZH: I didn’t think I wanted to work with teenagers because high school was so hard for me, socially. But I came and volunteered, and working with youth completely changed my life.

ES: The origin story of our relationship and even our connection to The Fields at Rootsprings started in some vacant lots in Buffalo and seeing how those spaces can captivate teenage imaginations, which is virtually impossible to do. It could be a place for them to work together, solve problems, imagine new things, set dreams for their lives, and create new communities and families. I don’t know if I just didn’t expect it, but when we moved to Minnesota things were different. I went into an academic space. We didn’t have the rhythm of the calendar year and the farm.

But in addition to being a camper, I also was a camp counselor and did a lot of things with young people and the woods. As an artist I’ve found nature and retreats to be pivotal to creating work and having space from the city, my cell phone, and reality television. It’s harder to get TikTok in the woods, and TikTok is in direct opposition to my writing [practice].

So, I started having a seed of a dream. Zoe and I both had great retreat spaces that helped us transition out of really hard work situations or to breathe new life into the work and dream about what we might make. It was that seed and conversations with Signe [Harriday] who is also part of the cooperative, that got this all started. We thought, “wouldn’t it be great to have a space where we could invite artists to come out and seed new theater work or work on writing?”

TH: So you both moved from New York to Minnesota?

ZH: Yes, Erin is from Minnesota.

ES: Yes, I moved to Buffalo thinking I’d be there for nine months and I ended up being there for ten years.

ZH: We met at this beautiful urban farm and food justice organization where we were teaching young people how to grow food but also really thinking about the food system as it is—and why is it like that? Why do some communities have access to food and others don’t? Why do some people have access to resources to grow food or have food-based businesses and others don’t?

We worked there for nine or ten years together, and worked with over 500 youth that we’re still connected to from the Massachusetts Avenue Project.

TH: That’s a whole other conversation! Zoe, what sparked your love and dedication to the land?

ZH: I grew up in Buffalo, New York which was really segregated. It is one of those post-industrial cities—segregated culturally, ethnically, and economically. It politicized me from a young age around race and class. It is a city that showed me and the world what happens when developers and big business interests get to do whatever they want. I think that pushed me into thinking about urban planning and economics and how resources are not shared. Although so many of us have contributed to the economic resources of this country, only some of us actually get access to them. So I was thinking about all of this before I got into food and agricultural spaces. I was raised in a single-parent family and my mom would, once a year, do a trip with other women and their daughters where we would go whitewater rafting in West Virginia. When I got old enough we would go every year and it was an incredible experience of being in nature. Experiences like those made me feel like nature is this amazing and special place to go to—it gives me access to all of this beauty.

I have also done a lot of thinking around us as women of color and organizers, and how we experience burnout. We sometimes learn it from our mothers, this concept of work, work, work—work on things in the community, work on our jobs, work on things for other people, and you let yourself and your own needs fall [to the wayside].

Getting into synchronized swimming with Signe Harriday, one of the Rootsprings Coop partners, became a way for me to embody care and do something that feeds and heals me. That’s also a really important connection point for Rootsprings and the work we are doing.

Before and throughout the uprisings, we were seeing all of these incredible organizers spiral out. They, we, were getting sick, experiencing so much trauma, and didn’t have the chance to process it or heal from it before other traumas came. Meanwhile, we had a lot of people around us—foundations and organizations—saying, “what do we need to do to support the movement?” And [we would say that] you need to support the people who are behind the movements.

TH: Right.

ZH: Many of them (Black and Brown organizers) have come to a place where they are physically sick, exhausted, making hard choices and stepping away from the work, explaining that they need to go to another kind of job that cares for them better. Thinking, “maybe I won’t be able to do the organizing work that I want to do, but I’ll be cared for.” We don’t want to be in a movement that doesn’t have space for healing and care—that’s actually part of the maintenance that is required for us to build these movements and do all of these things—police abolition, food systems development, and all of the things we’re doing.

Rootsprings is one of those things that will help. You can feel it when you go to the land. It’s an energy shift. When I go to Rootsprings and I’m surrounded by all of this incredible nature, I’m reminded that I am nature and that I’m connected to it all the time. It’s a perspective thing but also a practice thing. We get caught up in work and technology, and all of these things that put layers between us and the ecosystem that feeds us.

Also, a lot of Black and Brown people don’t have cabins up north or a place to get away. We don’t have these kinds of spaces but we should have access to them—spaces that help you feel free. Throughout [the pandemic], when we were getting so much cabin fever, it felt like we just needed to be out in a space that is natural and beautiful—not stressful.

TH: That’s so real. A lot of what you’re saying applies in Chicago. It’s something I see and feel myself, but I especially see it in the most present organizers here. And it makes clear how recovery is a strange thing because it’s not as if it’s static. I know that I, myself, as well as the many people who are doing work on the ground in Chicago rarely get the chance to even take some time to get to a place where they can say that they’ve recovered—whatever that means to each of us. We are in a perpetual and cyclical state of recovery.

ZH: Right! That’s so true.

TH: Which is why the mission of what you’re doing is important. So, I want to start by breaking it down—what is The Fields at Rootsprings, and how is it composed—as a cooperative and organization?

ZH: Yes. The Fields at Rootsprings is the partnership of our land equity co-op, Rootsprings, and The Fields, our nonprofit. Both important parts to make what we’re doing work.

ES: The Fields is a nonprofit that we took over when we got into a purchase arrangement for the land. It’s a nonprofit that was fairly dormant. They wanted a relationship where there was a [separate but direct] relationship between those stewarding the land and those doing programming on the land. We saw this as a big opportunity to think about the dynamic around a group of Black folks, women of color, and queer folks owning land together. We wanted to talk about what ownership means and how stewardship adds to the conversation. Having The Fields allows us to be nimble and think about how we bring money into the organization.

Of the six of us who are part of the cooperative, three of us are on the board at The Fields. I’m the chair of the board, and we also have artists and community members on the board. We imagine The Fields might also offer us the opportunity to support other land projects in Minnesota in the future. We could use the nonprofit to mentor someone else or raise funds and help another organization or group of people who want to do something similar. Within The Fields we are organizing with another Black land project and other groups looking to do different kinds of projects.

ZH: We sometimes describe it like Rootsprings Coop is the theater space itself and The Fields is the nonprofit production company that leases the space but does all of the activity that gives the theater space life. We’re still figuring out the best ways to explain this to people.

TH: I see. Can you talk more about the land itself?

ES: Rootsprings is about an hour and ten minutes north and west of Minneapolis. Minnesota is the state of lakes everywhere, and this land gets into cabin country. We have 36 acres of land. That land is in a lot of different biomes. We have the forest, wetlands, marshlands, and prairies. On the land there’s a small lake and three small hermitages or cabins on the land. We have a farmhouse and barn. We have a wellness center with a sauna, also a kitchen if you want to cook for small groups.

There’s also a bodywork room there, in case folks want to work in a massage during the time that they’re there. We also have a walking labyrinth for meditative work—or rather meditative non-work.

We have a little gaggle of chickens, guinea hens, and a guinea fowl. A couple of barn cats. We have a hefty garden and an orchard of fruit trees.

The land was acquired in the early 1980s by a group of nuns whose mission really was to provide respite and support folks in their networks who needed respite. They hosted people from across the state and the world who came to swim, sit in the hot tub and get massages and food made by the nuns. They did that until about six years ago. Then they sold it to a couple—Joan and Dan—who stewarded it until about a year ago.

It had a white lady spirituality feel to it. It was covered in iconography and images that were inspired by a Catholic tradition. And many of their guests were white women over the many years. After five years or so, Joan really had the heart for wanting to turn it over to BIPOC leadership. So, she invited five Black women who were doing interesting work [to see the land and have a conversation]—Signe [Harriday], who is part of our cooperative, was invited to come and see the land. I went with her because we had been dreaming about retreat spaces and had both heard of Wellsprings [which is what it was called before we took over]. That happened in June 2020.

I went into one of the hermitages, the geodesic dome, and I instantly had the feeling that I could write a book here—in this space. Something about it felt like the right scale, distance, awayness—the smell of it. So they offered opportunities over the course of the year to guest-host on the land and to have our community come out. We invited our community because we wanted it to be a collective decision. We wanted them to affirm the idea and say, “Yes, we can use this and this is something we could utilize. This could be an answer for some of the things we’ve been asking for.” In the winter, we formed this cooperative and started fundraising. Then, we took over in February.

This has been a really challenging 18 months in Minnesota. In ways it’s been challenging for everyone, but in Minnesota, it’s been really challenging. Zoe and I were living right in the center of the city and had been organizing in Minneapolis for several years. We could really feel the ways that people were having fatigue.

When George Floyd was murdered in our neighborhood, it wasn’t the first public execution by police in our community. The organizers that mobilized to support the community in the face of the uprising had mobilized before—and before that, and before that. And they were sleeping in tents outside of the 4th precinct when Jamar Clark was murdered.

I could see amongst my friends the ways that trauma was manifesting in harm among us. All of these resources flooded into Minnesota—more money than we’d ever had access to. I’d be hustling as an organizer and taking tiny resources and spinning it into gold, and suddenly, we finally have a full bank account, which sparked all of these strange feelings around jealousy and criticism. People would be saying things like, “Well, you hurt me before, so you couldn’t possibly do this right?” Or, “Why did they pick you? You’re not Black enough.” Or, “You’re queer, how can you serve Black people?” The amount of arrows flying everywhere.

ZH: Yes.

ES: And it wasn’t new. I can actually trace its origins back five or six years. A storm of call-outs and accountability comes with an influx of resources. It’s really hard to deal with.

ZH: We’ve also talked to other reporters and journalists who want to hear how Minneapolis and St. Paul are doing and how Black organizers are doing throughout all of this. It felt like there were several revolutions happening at the same time. So, you had Brown, queer, and trans organizers doing amazing work, but also a lot of separation and cleavages in the Black community. When all of this money started coming to Brown queer people from all over the country and the world, stuff got real angry. All of those schisms got ignited. And [that made it clear that] we have such a need for healing if we are going to be able to abolish the police, or create a new public safety system that’s life affirming, we’re going to have to figure out ways to work through these cleavages and the ways that we are cracked and divided. We need to do healing work.

That also was part of the question: how can we foster a space to do healing and work through how our traumas and the interlocking systems of oppression that make us go at each other and keep us from unifying against our oppressors. We’re excited to work with groups doing transformative justice and reconciliation work.

TH: As someone who first took in your work with The Fields at Rootsprings from a distance, one thing that I really appreciate is that this whole thing is under the vision of three queer couples. It is an effort that is literally birthed out of love. It’s really beautiful to not only have a cooperative, but to also have a cooperative that is intertwined with these relationships and taking it to the next level.

ES: We’ve all orchestrated things. We have a college administrator, someone who has worked against huge multi-national corporations, we have grassroots organizers, theater producers, and directors—very interesting and valuable skill sets for this work. But we’re also organizers, so there’s a lot of facilitation. We’re learning about one another in new ways, which is really exciting.

But, running a retreat center is also about doing laundry and work you have to do to maintain it and center the experiences of our guests. A focus on hospitality. To start out as couples and friend couples, also to have worked with one another in other spaces, it brings our relationships to a new level. We’re learning from one another in new ways. We’re stretching. These are all new things for us—and exciting.

ZH: We’re learning about how we each want to relate to the different aspects of this work, the hosting, the farm work, the administrative and programming work. There’s a lot that we’re learning, and have learned about starting a coop, fundraising and purchasing land—all things that we want to share. And we’re also still learning. But it’s been really cool to find a community with others doing Black and BIPOC land projects here and across the country.

ES: We also have to educate our philanthropic partners because they don’t understand this. They ask questions about why they should fund cooperative business models. There’s a lot of excitement about the idea, but the work of shifting their understanding of how the funding can work differently can be challenging. We’ve had a lot of success with individual donors, but donor education is a longer-term thing. And as we’re learning, there are some forward-thinking foundations that are helping us with that learning and figuring out ways to teach along the way.

ZH: As you know, Tempestt, cooperatives are a way to make organizing economically and many other big things our people need possible. Erin and I would have never been able to purchase a piece of property like this and do this whole venture by ourselves, but as a cooperative it’s possible and manageable. It’s something that our collective skills and connections can do. Cooperatives are such important tools for creating agency and autonomy in farming, housing, financial services, and schools—the ways that communities are trying to create systems that serve us, when the mainstream ones won’t.

EH: Funders understand that revolution is happening and we’re in the midst of it. And the nonprofit industrial complex is fueled by foundations that want us to do things bigger and better, more innovative, and new. As opposed to us doing the work that gets us out of the [root] problems. Identifying the essential component of organizing that is respite, rest, and care. We need time away to think and be strategic. You can’t just tack it on as a quick retreat for staff. It is essential.

ZH: We talk about this in the abolition space. It’s not just about tearing down the antiquated systems that aren’t working for us. It’s also about creating new ones, and that takes so much learning about our systems and how they came to be in order to plan for new systems that are wholly different from what we’ve been told we could have. We need space for ideation where we can come together and talk about how we’re going to build those things.

TH: With all that you’re saying, so many things come to mind, especially about educating funders and what role they can play when it comes to cooperatives. We also know that the nonprofit structure was not created with folks like us in mind. In many ways, it was created for and continues to be for people who already have access to wealth, resources, and a network of people who also have wealth and resources. To me, any funder who is actually trying to put support toward any form of Black, Brown, Indigenous, or queer revolution needs to understand that nonprofit isn’t the way to go.

“To me, any funder who is actually trying to put support toward any form of Black, Brown, Indigenous, or queer revolution needs to understand that nonprofit isn’t the way to go.”

ZH: That’s so true. I feel that the nonprofit sector became a way to address the systemic problems, symptoms, and outputs of problematic systems that are not built to give everyone things like healthcare, or education, or economic autonomy. They are band aids for people who are living without. The arbiters of power don’t intend to give the big social safety nets so that people can get good housing or healthcare or food. And since they’re not going to make that possible, here are these nonprofits that can kind of get people along. [Through cooperatives], we’re challenging this and saying, “No, we actually need assets that give us the ability and the wherewithal and resources needed to create our own destiny.”

ES: There’s also a lot of pressure in that, too. For instance, we can’t fail because that sets people back in terms of others who want to do this work. It also takes a lot of thoughtfulness to not replicate systems because they’re sneaky, right? I think having time, space, and resources to do good work in terms of the thinking, imagining, and creative problem solving part is really important. There have been many attempts to do things differently, but it ends up being the same boat, just a different color boat. So, how can we really get to the root of these things?

TH: I imagine the other coop members will have their own answer, but I want to ask you: If you’re creating a place for healing, rest, and respite for the sake of world-building, how are you both taking care of yourselves within all of this knowing how hard it is and what you mentioned before about the challenges of organizing?

ZH: Having a place like Rootsprings to go to, even though we’re working and building it, it provides respite for us. We had Erin’s family there, we spent a long weekend and went fishing, cooked out, and spent time enjoying it [ourselves]. It’s also a reminder and resource for embodying the things I know that I need. We not only need to work towards liberation, but we also have to figure out ways to be free as we work towards that future freedom. I practice synchronized swimming, use somatics, and try to take respite, to help me navigate organizing against the oppression machine. And then, working on making Rootsprings a place that gives respite to so many in our community who really need it.

ES: It’s convicting. I can’t keep telling my friends to spend time at Rootsprings when I’m not doing it myself. As soon as I hit the gravel road leading to the farm, it’s instant. While I’m there, time works differently. It’s cool to have a place to see through all of the seasons. It’s been the same land and different land over the past 8 months [since we acquired it]. It has its own personality. We were there during a meteor shower, you see the stars, you see the dome of the sky. It’s such a gift.

ZH: The sounds and the birds. The cranes that come down on the lake. The swans. When you’re surrounded by it, you think, “this is what I should be doing. This needs to be a regular part of my life.” That’s what I hope people get from coming here. And we want to facilitate that—to say, “hey, you’re a Black writer, artist, organizer. Can you figure out a way to make space for respite once a month or once a quarter? Or for your organization? Make that part of the work so that you can maintain your creativity and passion.”

ES: We have a group of committed people who have pre-purchased nights on the land. They have ten nights this year and spread it out how they want. It keeps us connected to a community of folks who are excited about this too. It has been, already, fruiting and producing benefits for us. That’s not the only purpose, but it’s been a great reminder. It helps me set my calendar and say hard nos so that I can say enthusiastic yeses.

We started the Black Abolition & Liberation Cohort which started meeting every day during the uprisings and thinking about Covid-19 and mutual aid. We’ve been helping folks through some conflicts. It’s been intense. We were trying to figure out a retreat because we’d been meeting in Zoomland over the past year. We decided to go to Rootsprings and started writing an agenda, but then started asking, “Do we even need an agenda…?” It was so nice because we got where we wanted to go—we got to deep relationship building and dreaming together but we didn’t force it. We could just make s’mores and look at the moon.

ZH: All of the truth about relational organizing and how important it is to build relationships so that you can do things together, the trust and level of commitment you need for good organizing. We need spaces and time to build those things. We’re excited about groups using this with the Fields at Rootsprings.

TH: Have either of you done retreats in other places before?

ES + ZH: Yes.

TH: You’ve talked about this a bit already, but I’m wondering if you can expand on how you’re thinking about Rootsprings differently?

ZH: When people want to come to the space, we try to get an understanding of what their needs are, and then also share information about how to be in community and care for the land—like composting and helping with harvesting and other sustainable systems we have here. When people come, we usually give them a tour, give them some history and show them what the place offers. We give them our cell numbers, then we just let them be. We have many offerings but don’t over program people’s time. Letting people find their own way feels really nice.

I had a really amazing retreat experience at a farm in Vermont that was connected to the Center for Whole Communities. It was coordinated with the intention of bringing organizers from different sectors together to dialogue and process some of our society’s big challenges in a beautiful space where our basic needs were well cared for. We got to slow down, had amazing food, we practiced quiet meditation, cared for the sheep on the farm, had deeply personal dialogues about our work and made personal connections. At the time I was preparing for a big transition. Erin and I were leaving New York and many organizations we built over the years and relationships in the move. The retreat experience was an important time for processing all the changes that were happening, grieving the things we were leaving and being in a place to look forward to new places and people. It was powerful for me, so I think about how Rootsprings can be powerful for others.

ES: We’re pushing against urgency stuff where we have to have everything all figured out and it has to be perfect from the start. We’re also doing an audit of the space and figuring out how the space can say yes to people. To think about different bodies—fat bodies, different abilities, and how to use resources that says yes more. Part of it is also acknowledging that learning how to rest and take respite is something that has to be practiced. It is something that is taught out of us often—we’re taught quick-fix things or to push things down in order to keep going or to rest. So, even though we want people to have a self-guided experience, part of it is also thinking about how that can feel really scary to those who aren’t too familiar with spending time with themselves and being outside of the city. So, we’re thinking about the experiences of the people who are coming to us.

Central Minnesota is also a little Trump-y…

TH: Central Illinois is, too…

ES: It really feels like you’re away when you’re at Rootsprings, but you can still get to a grocery store that’s eight minutes away. But you also have to drive past a Trump store to get there. You have to drive past places where people are using fences to say terrible things about women leaders in our state. So, we’re learning and wanting to be responsive, keep it emergent.

We’re not just building in opposition to something, but we want to be building in a way that’s thinking about what centering folks like us looks like. And for those who are even more de-centered in this work than we are. We want to understand and recognize our own privilege. We want to think about how as a cooperative of Black and Latinx people can be in relationship with the Dakota people who have been stewarding this land for forever. We have a lot of questions coming up, so we’re trying to feel the questions and not feel that they all need to be answered right now.

TH: I appreciate these answers because I’ve only had a couple formal retreat experiences and they’ve actually been really hard. For one, it was hard to feel deserving of that kind of care and such luxury and not pack the time with the burden of productivity—which is something that I am constantly trying to work through. Also, the safety piece was sometimes a big one. There were times when I didn’t feel safe and that really got to me and impacted my ability to enjoy the experience. Also, all of these experiences were white-led and there usually wasn’t a queer person in sight.

So, going back to what you said about what the past year and a half has been for organizers, what has the response been to the space from organizers outside of yourselves?

ES: I just want to reflect back to you that I’ve definitely been to retreats where I go into it thinking, “They gave me this retreat. I need to get this thing done during these days and when I leave here I need to have a plan or to have written 40 pages…” It can be really stressful, especially when you’re trying to figure out if the inspiration is hitting. So, we want to invite people to really rest—it’s not about productivity.

We had a group from a place called Irreducible Grace Foundation—a theater group for young people who have experienced foster care or are foster care adjacent. We had the most guests on the land at that time and we also had people from the Million Artists Movement. [Irreducible Grace] brought a bunch of young adult leaders who kept asking, “We can just go wherever?” And we would say, “Yea!” “We can go swing in the tree? Go into the cabins?” And we were like, “Yea!” “And we can come back here?” “Yes!” They were so excited. They even did a meditation at the labyrinth where they asked, “Think about a question you have for an ancestor about ways of achieving public safety that centers us.” It wasn’t exactly that, but something like that. Then, someone took quotes from Black and queer ancestors and placed them in the labytinth for people to find. So they walked the labyrinth and thought about their answers as they walked out. I want more experiences like that where young people are lying in a hammock, picking fruit off of trees, and finding frogs. It was a youthful glee.

They were also so surprised to know that we were the ones who owned the space. And I would say, “Yea, I’m surprised, too!”

We want them to be affirmed that this is for them too, and we want it to be accessible. We want people to come back. When I’ve done retreats I’ve had to apply and hope they pick me. Then half the time there’s imposter syndrome. But we want people to come back again and again.

ZH: Or to say, “I have a share and this is a regular thing.” We all deserve time, space, connection with nature, and a spiritual and emotional peace that comes with that connection. I definitely grew up without a lot of those things. And went to retreat spaces that didn’t feel like they were for me. I felt watched, like I or the youth of color we’d bring would damage this pristeen thing, we’d be too loud or somehow damage these places managed and owned by white people. And that’s policing! It feels amazing to just have a space where we don’t have to feel like that, where we are welcome, and that we deserve this!

I have a friend who is a Black and Indigenous farmer and she’s said, “I just want our people to feel entitled. Wouldn’t it be an amazing thing if we could feel entitled to things?” I want to see kids who just grow up with this and are like, “We have a retreat place that we go to where we do all of these things…”, know that it’s there for them and all of our communities, forever.

TH: Last question. A lot of what you’re doing or have been doing within the different communities that you occupy, you’re dreaming up something incredible. A year ago and before Rootsprings was a thing, one of the dreams was to have land and create a place to go to. Now you have that. So, knowing that dreams are perpetually created, shifting, and manifesting along the journey, what dreams do you have now for yourselves and your communities?

ZH: I’ve had a recurring dream since we started the process for developing Rootsprings where all our people, family and friends in activism and the art world are there on the land. Erin and I are there on a deck looking out to all of our folks and their kids—they’re swimming and jumping off the dock into the lake. They’re canoeing and picking fruit, giggling and running around with no one telling them to be quiet. They’re exploring nature and experiencing all of this. And it just feels amazing. It’s a recurring dream I have of our people just using it and having space to relax and be free. And it’s starting to happen.

It’s beautiful to see all of these BIPOC and Black-led projects that have cropped up over the past few years getting resources to make these long held dreams a reality. And many of us are helping each other, sharing what we know and connecting each other to the resources that make a difference.

ES: Similar dreams. I’m excited about the resources that we’ve been able to raise so far and the more that will come. I’m excited about us being thoughtful about Rootsprings and not needing to get bigger and bigger. We can keep an understanding that we don’t need to scale up, we can be in relationship with the natural systems of the space and people. We don’t need to gobble up more real estate, make it bigger, or cover the land with more gadgets. I’m dreaming about the ways that the land can hold us more and our folks more. I’m dreaming about a time when things like this aren’t super novel and more people have heard of [or created] something like this. We can’t hold all of the people who want to be at Rootsprings, which is cool and okay.

Zoe and I have been renters forever and we haven’t been homeowners before. So I’m also thinking about what inheritance looks like as queer people. How can we think about what we leave and how can we imaging that outside of heteronormative structures? Also, how can we think of stewardship long term, through relationships.

I’m also excited about spending October there. We don’t want to get ahead of ourselves and think too far down the road. I think that’s sometimes an issue for me because I sometimes ideate too much.

ZH: We have talked about a lot of things we want to do. Like Signe is a theater producer, so she wants to do plays and productions out at the farm. Erin and Free Black Dirt do these incredible salon style poetry gatherings and writing workshops. We have friends who are musicians and we’ve thought about concerts and even coordinating artist residencies. Erin has even thought about things like green burial. We’re trying to balance long term things with the value of the open space and it not being jam packed. We have a lot of ideas, but I do think it’s like what you said, babe—we can balance it with just seeing how things go.

ES: Right. We don’t need to always make work. We can also just be responsive and move into things with trust-oriented time.

ZH: When our communities—communities of color and queer communities get resources, we build systems and things that are beneficial for everyone.

TH: I think it’s important to restate that it’s about so much more than just land. A lot of the work you’re doing are practices that are in our blood and in our bones. There are endless possibilities. I’m really excited about the blueprint you will all create as artists and organizers. Your work has been nourishing for me, even from a distance. Thank you for the work that you do.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Matt Austin.