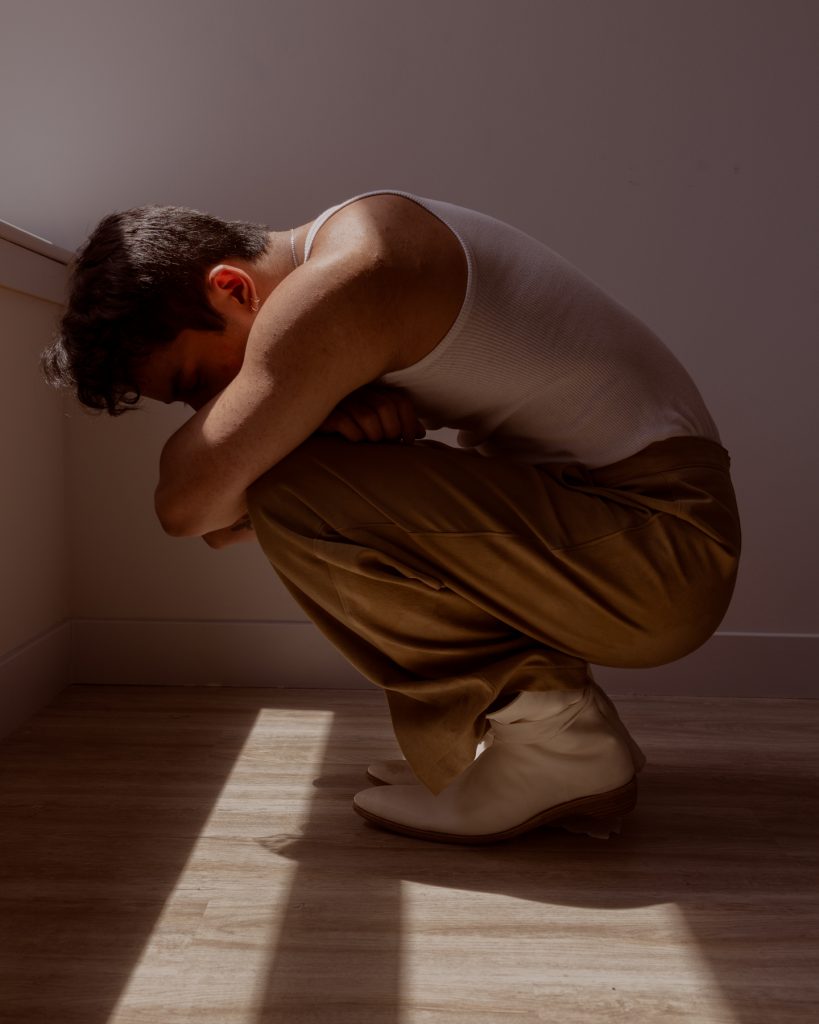

Featured image: Sam Fissell is in a backwards crouching position on the floor with his back to the viewer. He is wearing tan trousers, a white tank top, and white shoes with a white cloth tied around the ankle. Photo by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

FOLD/UNFOLD: fashion designers and artists on dress, tactics, community, and power in zhegagoynak/zhigaagoong (Chicago) and beyond.

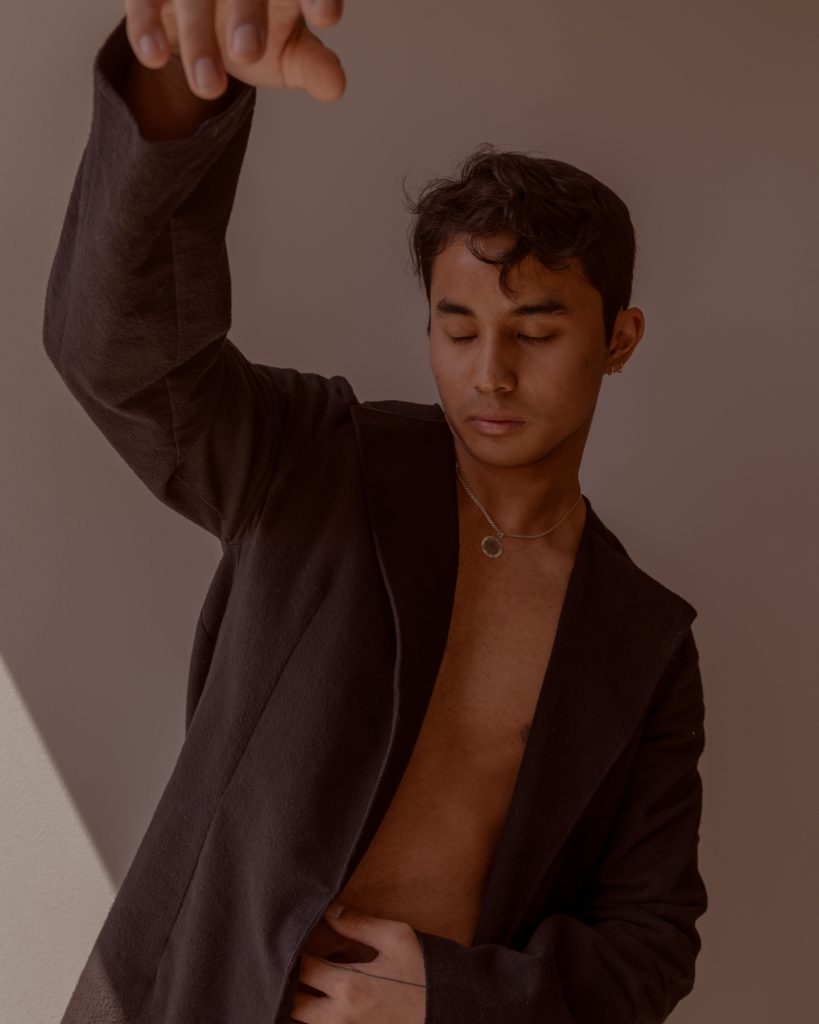

Sam Fissell’s light-washed apartment is sparse, modular, and neat. As a fashion designer, he has made the space feel ready for anything. Fissell’s approach gives a mix of precision and unpredictable intensity – someone who gets things done, but who also wildly trusts collaborators and leans into the unknown. Talking to and witnessing Fissell, you can feel his commitment to process over product and to the relationships and inheritances that make fashion matter to begin with. Care emanates from him as he picks minute pieces of dust off a garment we’re documenting from his most recent collection, crossing his legs to showcase the white leather boots his friend made for the collection. He holds that same care in our conversation as he assesses the cultural appropriation of beloved fashion houses like Margiela; he shifts the focus from the obviousness of the appropriation itself to what it would take to actually support non-white designers who consistently have their work stolen from them. In our conversation, Fissell highlights his identity as a Cambodian-American fashion designer, his investments in tailoring, the way his collaborations (including with his mother!) resist the romanticization of the individual artist, and what the slowness of Chicago does for his process.

row särkelä: Who’s your favorite fashion designer at the moment?

Sam Fissell: If I had to choose, I would say Martin Margiela – particularly his early years, like 1989. He made the iconic Margiela tabi boot after going to Japan with Jean Paul Gaultier. He wondered what would happen if he put the traditional tabi flats into a thick heel. I love the tabi boot, but there is definitely an interesting conversation [on how] we yell ‘appropriation’ at people we don’t like, but then for people we love, we don’t assert the same standards. My friend Max did his dissertation on some of the appropriation of the tabi. The tabi is a traditional thing in Japan, and I don’t think [what Margiela has done is] any different from people taking kimonos –

rs: Right, it’s always no to John Galliano for doing that, but yes to Margiela –

SF: Okay, but there’s a lot of [appropriative] stuff for Galliano [laughs] –

rs: Okay, true, but everyone stays on the RealReal lining up for almost full price Margiela tabis. And I’m not saying I’m any different. I love tabis, I have the Nike ones. But what about the craftspeople who made that aesthetic? What’s your final word on if we should be wearing tabis?

SF: I think there needs to be a larger conversation about appropriation. If Margiela outsourced the creation of tabis to the craftspeople themselves, the creators of the tabi, then that could be one solution, but on the other hand, [the craftspeople] might find that very offensive and it’s really about what they want. It also becomes a problem of who you are paying, because there’s so many people who create traditional tabis. It’s not as simple as redistributing a random amount of money to one person.

rs: My partner Madeleine Le Cesne was telling me that after the Black employees of Glossier made a set of demands for better treatment, Glossier met one of their demands by investing in Black makeup startups. So maybe it’s that Margiela uses their position to invest in young Japanese designers.

SF: Yeah, that’s a really great solution. And not just Margiela, but heritage houses [like Dior, Gucci, etc] in general need less power over the industry. I don’t think abolishing heritage houses is the solution. I think it’s giving as much props to smaller designers, or splitting the money between heritage houses and people who are coming up. Emerging designers need the money more than heritage houses do, but the rich customer base doesn’t really think like that. The younger generation is very aware. We’re all just very tired of the same shit every season. At the top, they know the younger designers are where it’s at. And that’s why they steal from us. Like Balenciaga stealing their interns’ work, and taking them in to take their ideas and then booting them out.

A contemporary designer I really admire is Peter Do. Peter Do is very new. He’s a Vietnamese designer who does contemporary women’s wear. It’s incredible to see another Southeast Asian designer make it so far. He worked under Phoebe Philo at Céline.

rs: Céline was my shit as a kid! I would always rip out their ads from the Vogues I would take home from the library leftover piles.

SF: Céline under Phoebe Philo is one of the most comfortable-to-look-at eras of fashion. Peter Do went to the Fashion Institute of Technology, then got awarded something where he worked under Phoebe for a couple years and had his own very small team in New York. The team’s thing is that they met on Tumblr.

rs: Phoebe Philo and Peter?!

SF: No, no – [laughs] the team [members] were friends on Tumblr and some [were friends] in real life, and then they came together. It’s sort of the antithesis of the age of the internet in the context of fashion. I have so many friends that I’ve met through Instagram or people who live so far away that enjoy my work and I enjoy theirs. It’s great to use the internet to your advantage in fashion specifically. I think it’s becoming a thing where we don’t need these big institutions.

rs: But what about access to things like digital pattern making? I wouldn’t know something like that existed without the support of a bigger institution.

SF: When I talk about institutions, I mean those that keep up the old guard traditions. I think there is a need for school institutions when it comes to learning work ethic. I’m so thankful for the instructors that have helped me and I’ve learned so much. They can make a world of difference. Or it can be the total opposite, and you can feel like you’re not learning as much as you could. I also learn so much from my friends and upperclassmen. Not being afraid to ask, actually: which teacher will help? Which teacher won’t help? You have to be honest with me.

rs: So much of your work is highly tailored. Was it scary to start learning pattern making?

SF: Yeah, it definitely was. Patternmaking is daunting. It involves a lot of math and geometry. It’s always a joke in my head that my algebra teacher, who I was always very cool with in high school, is laughing somewhere. Ha! I didn’t come into college as a fashion person. I always had an interest in fashion, but the application of it didn’t come until my sophomore year.

rs: I definitely feel like fashion is something that I’ve finally decided it’s okay if that’s all I want to think about and work on. I was just on this trip with eight of my friends and everyone was really into fashion, but we’d never even talked about it with each other. It’s not “art,” right? It’s not high theory. I feel like fashion still has a lot of layers, where people are like, are we really going to just spend all day talking about Prada? And people do get so excited when you spend the day looking at archival shows! But I think there’s so much bias against taking fashion seriously, even though I’m not even interested in fashion being serious, just that it can be something –

SF: – to live in. I totally agree. There’s so many different layers of fashion. It is what you make of it. I think for the person who doesn’t define themself as artistic, who’s outside of communities where art is who we are and what we live for, when they see fashion it’s like a commodity.

rs: I think that’s the biggest thing, right? The relationship seems only like commerce to people. And since so few people in their twenties or younger know how to sew, it feels less accessible to make garments for our own needs.

SF: And with the expansion of fast fashion, too, fashion has definitely become much more commodified. The tradition of the art – the hand-sewn stuff – is something only for couture houses instead of for everyone. It sucks to me. You have to move with the times, obviously, but I think it’s okay to miss the handcrafted elements.

rs: Why do you love fashion? For me, I just love to see how people interpret the world on their body. It’s a site of intimacy and violence. People are always making these intense decisions about how they want to be perceived or not, how they want to show up for the community that day. It’s these all the time, every day enactments; and that’s why I’m so interested in it.

SF: Yeah, this is a difficult question to answer. For me there’s a lot of cultural reasons, [there’s] personal information that’s imbued in my work in terms of where I come from. I’m adopted, I’m Cambodian American. There’s a lot where, with my past two collections actually, it’s been about the in-between. I talk about this a lot, the space in between two identities; my identities being very American on the one hand – there’s no denying it – and obviously my Khmer side as well, sort of fitting in between. I’ll always feel American. Where I went to school I was surrounded by whiteness. It’s not a hatred thing, I just didn’t have people I could relate to as hard so I didn’t fully fit. You grow up and you see things more and more and you try to learn more about yourself. Using fashion as a medium to explore that is at least, for now, my big thing. And my first ever collection was about that.

rs: Do you feel like you’re connecting with your specific ancestors in this collection? What is the form of connection for you?

SF: I think that’s a difficult question. It’s something that I’m still trying to figure out by looking through archives and looking at traditional Khmer-wear, by looking at how the silhouettes hang. There’s so much symbolism in cultural wear and I think it’s one of the most beautiful forms of any sort of fashion. I’ve been to Cambodia. It was definitely an experience that’s hard to put into words. I was so happy the whole time I was there, but I was also sad, because they looked at me as an American. Cambodia is where I was born, all my blood is from this country, but I can’t relate at a certain level. I think that shapes who I am. I would love to make a collection with a designer who grew up and works in Cambodia. I never had any Cambodian friends growing up. The first Cambodian I ever met was in my freshman year of college in Chicago, and it was the first time someone asked if I was from Cambodia right off the bat.

rs: In your most recent collection, I saw that you collaborated with your mom, who made beautiful metal buttons for your garment. Has she been an artist for your whole life?

SF: She’s actually a professor at Johns Hopkins University. Her art is a big part of her life, but she just started hitting her stride a couple years ago. Her buttons are incredible. We ask each other questions about process. These rings of hers [points to a set of rings on the coffee table] are in the shape of crocodile claws and were one of our first collaborations. The crocodile is one of so many animals in Cambodia that have a lot of significance to me.

rs: How would you describe your work to someone who has never seen it?

SF: I think that my visual language is a mix of identities. The way that I want to showcase my work is always through the past and the present, and showcasing my journey as an adopted Cambodian fashion designer.

rs: I feel like the work is very structural and that you care about tailoring.

SF: Yeah, tailoring is a really big thing for me. Showcasing good technique, the interworks of a garment, the structure, and what holds it together. I think it’s the same as any sort of human identity – there’s pillars and then there’s stuff that’s more fragile. I think there’s a lot of interesting ways that you can work tailoring into that idea. My good friend Todd [Barrera-Disler] said that clothes are meant to be worn. I love seeing clothes get dirty and worn. There’s certain things that obviously I would like to keep intact. At the same time, I love to see a pair of shoes get beaten up. There’s something beautiful about that that I really enjoy. I don’t think clothes are meant to sit in a closet. Archival stuff is cool, but I think you should wear archival stuff. I think it’s part of the story.

rs: How do you channel inspiration?

SF: I like a little balance when it comes to mind, body, and raw emotion. If you go too far in any of those directions, you get lost. Having a balance of chaos and organization, feeling and analytical mindset, you find some really great work because you’re pulling from all pieces. You go too chaotic and think too much, and you fall apart. If you go too emotional, you can end up in places you don’t want to. You have to take care of yourself. Me and Madeline Hampton talk a lot about good balance. You and I were talking about how we organize, do the mood boards, and what we want to say, but we never anticipate the shot itself. There’s joy when we see it get developed. Sketching it out and saying, “This is exactly what we want,” is redundant for us personally. And so far it’s worked beautifully.

rs: A lot of the editorial work that exists right now in magazines is pretty formulaic and top-down, maybe because it’s missing that element of trust in the collaborative process.

SF: Collaboration is such a huge part of my work, not just with Madeline, but with other close friends and family, like my mother. To trust the process and trust the other person is one of the most important things in my work. I trust their artistic vision, I trust myself, and it hasn’t failed me. Without trust you anticipate too much and then get disappointed.

rs: A lot of people’s unwillingness to do that is a product of fear and time. I know when I don’t collaborate, a lot of it is because I’m afraid I haven’t done the work to show up well in the relationship. Have you had moments where your trust hasn’t gone well?

SF: I think there’s definitely pieces where it’s not easy, where me and a collaborator won’t have the same idea, and I’ll push for one thing and they’ll push for another. But I think it goes back to that thing with trust where, so far in my life, I’ve had some really great friends and collaborators where we end up on a choice we’re both happy with. We might take both pieces from one another and figure out a medium. Sometimes I’ll flip and be like, actually you’re right, I thought about it last night and this feels like how it should be. Or sometimes it’ll be the opposite. I’ve been very fortunate where I’ve never had any big moments where it collapsed. And I think I’m a pretty level headed person. I’m not one of those people who needs it to be my way or no way, because I think that cuts you off from yourself.

rs: I think that’s part of what makes your work exciting – that you see that it’s made of many people.

SF: Yes, I’m very open about that. I think it’s good to not have that hidden. I know some people do collaborate but still present it as their work and their idea. I’m very open about saying that I’ve collaborated and there’s many people who help me with what I do. It’s very important to me.

rs: How does care show up in your work?

SF: It is something I actually think about a lot. There’s a romanticization of the artist, the individual artist, who does everything themselves and works tirelessly, sacrifices a lot, and doesn’t get enough sleep. Artists specifically put it on a pedestal – to be alone, do things yourself, a fashion person who does their own work and takes their own photos. It is commendable, but [as you] become more mature, you realize that is not sustainable mentally. You have to pace yourself, because fashion is very analytical. People who don’t study fashion or who are outside of fashion don’t understand how analytical it can be. Patterning, for example: you start with an idea, go through many sketches, and then you have to figure out how to make those things. That is very mathematical, you want to know the size, the proportions. It’s not easy, it’s planning. A quarter of an inch can make a difference. In two days, you can’t flip a collection. You can draw something in two days, but you can’t pump out a collection. It takes a lot of work. You need organization for your mental health. If you kill yourself over doing the work, it’s too much. I’ve definitely done the night before thing before, and it’s not healthy. Anyone who’s done it enough, you don’t do it too much after that. You learn very quickly that you get burned out. Pattern making, sewing it together, and making sure everything is finished well—it’s a whole process. People see the garments as a product, but don’t understand the work that goes into that. The drafts, the muslins, it’s unbelievable.

I have many friends who are not in the art world who have supported me for a long time with anything I do. Words of encouragement are a huge thing for me. I have friends back in Baltimore who are constantly asking what I’m up to and they’re so happy to see my work. It’s a loving thing and it keeps me going. It’s really nice to have those friends who are outside of the fashion world. I’m giving them a taste of the end product and showing them the process. It’s so fun because they don’t know anyone else who is a fashion designer. The excitement and joy that they see not just from my work but from fashion itself, is like them seeing it for the first time. That’s how I want my garments to make people feel – having something that they haven’t felt before is very important to me. My friends outside of the art world regularly give me that feedback.

rs: How is it being a fashion designer in Chicago?

SF: I love Chicago. Compared to some of the bigger cities with fashion schools, it’s a lot slower paced. To me, that’s a huge benefit. It might not be to everybody, but being able to have my own time and slow down really helps my practice; being able to go outside and not feel swallowed by the city. We have an amazing arts scene, great places to eat, but it’s a lot slower than New York. It allows me to process my own work and events in general, rather than jumping from place to place. Chicago has a really underrated fashion and arts scene. I love the people that I’ve met. It feels so fresh and very different in its own right [compared to] the other two, L.A. and New York. There’s this newness that is coming from this place that isn’t seen as a fashion hub, but we want to take on that challenge of not coming from New York or London. Todd Barrera-Disler, Jackson Napier–they’re doing amazing work on the same level as anyone else, but it’s got a Chicago flair. I haven’t been here long enough to say exactly what the feeling is, it’s there but I can’t pinpoint it.

Less pressure helps so much. The pressure in New York, a known fashion hub, of people getting these huge internships at massive companies, people getting discovered, people getting invites to shows–you have this feeling that you need to get off the ground now to catch up or solidify your place. I don’t feel that here, which is so nice for an up and coming designer. I don’t mind the fast paced nature. It has its place, and especially as I get more mature and confident in my process and work, I work faster and faster and I’m able to keep up at a pace where I can put out good work and also take care of myself. I think having the relaxed pace [here] helps because I don’t think I’m being hounded by my surroundings to be way past where I actually need to be.

I would love to see Chicago become as influential as another fashion city. One of my goals this summer is to start producing more, have more sample sizes, have a small collection, produce at a larger scale, and get my website up and running. It’s a very exciting thing – to have pieces I produce that people can wear every day rather than just couture.

rs: Are you reading or listening to anything right now that’s impacting your work?

SF: I’m a big music person. It’s one of the formats that I can do every part of my work to, from the sketching and the patterning, to the cutting and the sewing. Music can be a part of all of it. I love Yves Tumor. Me and Madeline’s last project was based on the feeling of listening to “Licking an Orchid.” We listen to the work so much. I love people whose whole life is their art, everything seems so fluid with who they are. That’s the kind of people who I’d like to work with in the future, people who are alive and are really envisioning my pieces on them in an artistic way. I’m also a really big fan of Dominic Fike, [who] I met once at RSVP. I think he’s part Filipino, and he makes amazing feel-good music. I love intellectual music, music that makes me think, but sometimes I just need good energy music, like when I’m cutting my patterns.

row särkelä is an organizer, artist, and white settler raised in tiwaland and living in zhigaagoong. in “fold unfold,” row addresses the seepages between fashion and social movement organizing, surfacing the work of designers and artists who shape and intervene in chicago’s vestiary landscapes. row considers taste to be a political project and investigates how design and dress unfold in relation to local forms of racial capitalism.