FOLD/UNFOLD: fashion designers and artists on dress, tactics, community, and power in zhegagoynak/zhigaagoong (Chicago) and beyond. *This iteration was written by row särkelä & madeleine le cesne.

Walking into fashion scholar Rikki Byrd’s house, the first thing you notice is the double archways framing the living room, a subtle nod to the soaring Gateway Arch of Byrd’s native St. Louis. Everything in the house feels intentional, like a lovingly passed down gift. While pulling up a chair at the 70s dining set passed down from Byrd’s step mother’s mom, a framed portrait of Byrd’s great grandmother comes into view, resting next to her grandmother’s hotcomb. Stacks of books on Black theory cover the dinette’s surface. In the living room, huge books on famous Black fashion designers like Willi Smith poke out from under the glass coffee table. Looking up, you see framed images of Zora Neale Hurston alongside a photo of Byrd’s mom as a kid, post cards, and magazine covers featuring Black figures in art. Everything is tactile and considered. You can tell that the person living here knows where they came from and where they’re going.

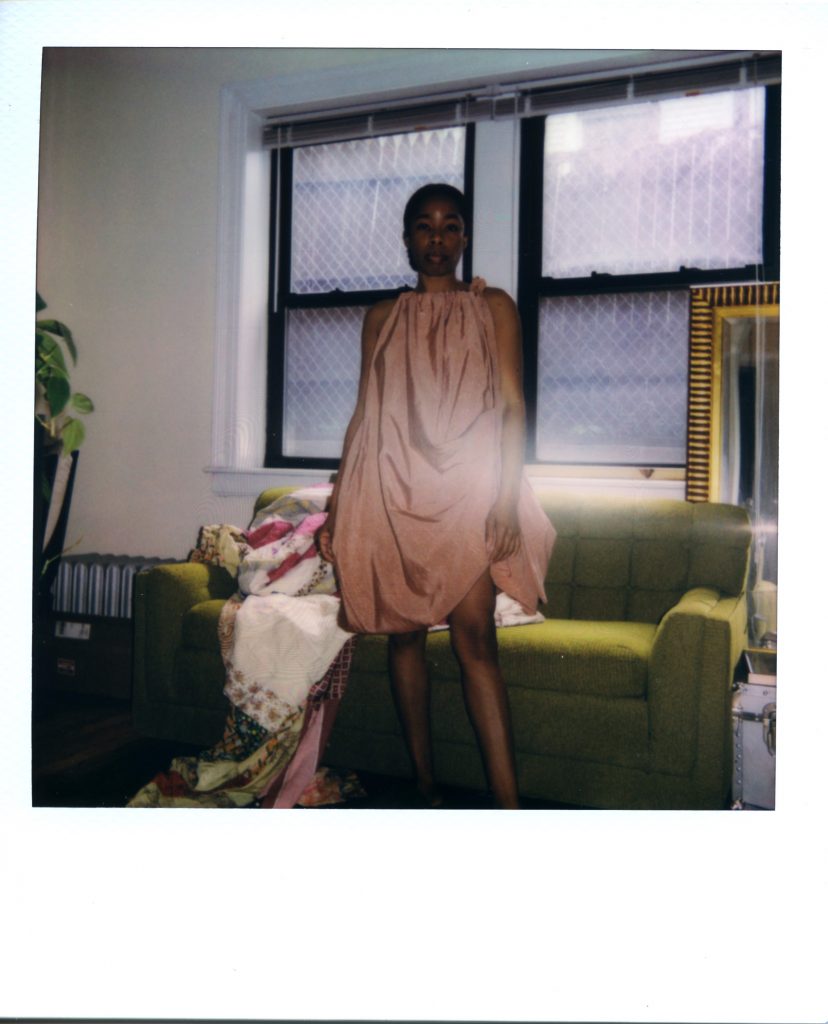

Byrd’s movements in front of the camera are intentional, too. She knows what she’s doing. Byrd’s mom is a fashion designer, and she laughs as she says that her mother asked her to model outfits all during her childhood. The legacy of women in Byrd’s family that have the power to turn fabric into art doesn’t end with Byrd’s mom — when Byrd pulls out her great grandmother’s quilts, we gasp at the care and artistry of the work. The love that Byrd’s mother, grandmother, and great grandmother show her is palpable as we take photos of her wrapped in the quilt. It’s freezing and windy by Lake Michigan, but Byrd is warm. This love is what animates Byrd’s work as a scholar, writer, and educator. People haven’t really told Byrd “no.” She gets what she’s after.

In our conversation, we talk about what might emerge if clothing and textiles were our starting points and core considerations instead of afterthoughts or awkward last-minute additions. Byrd shares about her research on Black funeral t-shirts, which she holds as a way to think about death and mourning in intimate and embodied ways. It’s important to me to frame this column with Byrd’s work because she surfaces archives and origin points that are typically ignored by dominant fashion theory. For Byrd, Black theorists like Christina Sharpe are the starting point for thinking about and experiencing fashion. This matters!

I hope, in reading this interview, that you feel the love that Byrd embodies. That you stretch in how you think about fashion. This one is long and super juicy and gets into grief and death, so I suggest having a glass of water nearby. As you sip, you’ll learn about which clothing item inspired Byrd to study the relationship between death, Black death, and clothing — and maybe even think about garments you wear that are part of your own process of mourning. You’ll hear about the path Byrd took to become a fashion academic and what a fashion academic even does. You’ll learn about thinkers who study Blackness and fashion, important Black fashion designers, and the questions we have to ask of archives to get answers that haven’t surfaced yet. Most of all, you’ll feel the gift of Byrd’s lineage. It’s palpable.

row särkelä: What did you study at Parsons?

Rikki Byrd: I was in their Fashion Studies program, which is a program that really invites people to think about fashion from all these interdisciplinary perspectives. There are people there who are studying the business or marketing [side] and, of course, I’m studying it from the African American Studies perspective. The program really allowed me to sink my teeth into my research and also provided me with a real closeness to the fashion industry that I thought I needed in order to get to the core of some of the questions that I was asking. I enjoyed it. And I had money from scholarships and grants as a student, but after I graduated I really wanted to go into a nine to five job, and Parsons didn’t have any teaching opportunities available. I was not willing to stay in New York City and just, like, struggle if I didn’t have to. It was a really good time, but I just noticed my body getting tired. I needed breathing room and the opportunity to live by myself, and so I came back home to St. Louis, which is where I’m from. I miss that apartment. I had an 1100 square foot apartment for $695 in St. Louis. So I had a lot of breathing room, and it was really good for me. Now I’m in Chicago and I have my own place, too. Some people are like, “You should come back to New York,” and I’m just like, “Not until I can live how I live now, or better!” I am not going back to that little box that I had.

rs: Yeah, my partner didn’t really know about the trope of how all the fashion people in Chicago are just here to make it for the small time before they go to New York and make it for the real time. I wonder how it is for you to come back [to the Midwest] from New York and how that different type of spaciousness feels for you?

RB: It was a big adjustment. Have you ever been to St. Louis or know much about it?

rs: I’ve only driven through it once, on the way home to New Mexico.

RB: That’s most people’s experiences: driving through, or they have a layover or something. St. Louis is characterized as this fly-over city. I grew up there and I went to undergrad two hours outside of St. Louis at the University of Missouri, Mizzou. I got my journalism degree there. Going to New York for Parsons was a shock, but then you get incorporated into New York and so going back to St. Louis was definitely different in that the hustle and bustle isn’t there, [and neither are] the events that you go to every week. But I was just at a place in my life where I needed to slow down. I [became] an adjunct professor at Washington University in St Louis. It allowed me financial flexibility and I’ve continued to go to New York a lot after moving back home. I knew that I wanted to pursue a career in the academy, and my interests didn’t require me to be located [in St. Louis or New York] in terms of archives. And Chicago is just a beautiful city that to me is the middle ground between St. Louis and New York. You definitely have the hustle of it and you feel like you’re in a city even though it’s the Midwest. The culture here is incredible. I do wish that there was more going on fashion-wise, because I think that [this] city has a lot of opportunity in that regard.

rs: What kind of opportunity do you think Chicago has for fashion?

RB: I just think that they have the resources, right? They have the really esteemed museums. They have the fashion programs where professors have been in the industry and where students go on from to have good careers in the fashion industry. [There’s] just something about all those things not really congealing yet to really create what could be a really great fashion economy here. I will say that the flip side to that is probably to the benefit of small business owners in that you do see a lot of boutiques that are able to survive here. I’m thinking of Sir and Madam, Notre, Fat Tiger, and streetwear designers like Joe Fresh Goods, who have really been able to sink themselves into the city and who know the city. They know the area and their designs and [their] work speak to that. Sometimes I do think it’s a benefit that it’s not this whole, “Chicago’s the next place for fashion week.”

rs: You were on the advisory board for the Chicago Fashion Lyceum, and I’m wondering how that contributed to your sense of what fashion is in Chicago, how designers are able to create more relationship-based work. I don’t know how you would delineate the congealing of a fashion world versus these designer-specific access points.

RB: The Chicago Fashion Lyceum is an incredible group of fashion thinkers, fashion scholars, curators, and people who just have an interest in fashion. The conference we were putting on was called Fashion at the Periphery. We were thinking about sites like Chicago or these areas that we don’t really tap into, not necessarily geographically based, but the fact that certain academic fields ignore certain topics of study. In the few conversations that I’ve had with them, I do think that they’re thinking creatively about not just Chicago, but about expanding the way we think about fashion being defined and centralized in a particular way. [They are] thinking about the four fashion capitals in the world, [London, New York, Milan, Paris] and what we are missing if we’re just focusing on those areas. What does it mean to really amplify the schools in Chicago? [When] I worked in the fashion program at Washington University in St. Louis, I would talk to people and they’d be like, “Oh, that’s cool, but I didn’t even know that Washington had a fashion program.” And we know the reasons why, right? It’s in St. Louis, but it’s also housed within this really prestigious university in the Midwest and it’s a creative field, and so it gets the least amount of attention. I think that those are the kind of conversations that the Lyceum is really trying to explore and tap into, to really account for the richness that we’re not thinking about when we just focus on those four capitals or [when] we just focus on Europe when we’re studying fashion.

rs: So you’re on the advisory board for the Chicago Fashion Lyceum, you’re a Ph.D. student, and you’re running the Black Fashion Archive. How are you managing all this and what is your current dissertation project?

RB: I keep my calendar updated, so that’s literally how I manage everything [laughs]. When I say I’m an interdisciplinary scholar and thinker, that’s really at the forefront of how I think about my work. [I’m] being really clear about what my strengths are and not limiting myself in exploring my strengths in different areas. Sometimes people are like, “How did you do this thing?” And when I really reflect on it, not that many people have told me no. Not many people have told me I couldn’t do a thing. A lot is certainly operating against me for a variety of reasons. If you don’t tell me no, I just go for it and I figure it out. I really like it, too, because it allows me to really decide what I don’t want to do.

I was interested in fashion in undergrad. Going into undergrad, the thing that you know about a fashion career is becoming a fashion designer and I knew for a fact I did not want to be a fashion designer. My mother is a fashion designer and I watched my grandmother and great grandmother sew and make quilts and I just did not have the interest — I just did not want to do this thing. But I fell in love with writing, and I really [went] for it.

My research since my senior year of undergrad has been focused on Black people’s experiences within the fashion industry. When I got my masters at Parsons, it specifically focused on the U.S. fashion industry and looked at different time periods where two things were happening. [On one end,] Black people were using clothing and textiles in their own ways to tell their own stories, create their own narratives, make their own mark, or really think about their identity or how they want to show up in the world. And then on the other end, the mainstream fashion industry was noticing these things and incorporating it into what they were doing. I looked at the 60s and 70s, when Black people were wearing afros and dashikis and really turning toward the continent of Africa to think about clothing and textiles and culture and art. And at that same time period, Black women were appearing, for the first time, in mainstream fashion publications. I looked at the 90s and early 2000s and the rise of urbanwear, so FUBU and Rocawear, and [thought] about [how] these white-owned brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren started to incorporate baggier clothes that [were] incredibly influenced by what they saw Black designers doing with urbanwear brands. And then I looked at the present day.

I had moved to New York [from St. Louis] a couple weeks after Michael Brown was killed [there]. And because I had done this research on the 60s and 70s already, I was really interested in how the fashion industry was going to respond. Because, I mean, Black people been on the cover of magazines — what are you going to do this time around? And so that’s where it became really beneficial for me to be in New York and have a particular access to the fashion industry. It became less [about] having access to knowing what mainstream publications were going to do or major designers were going to do, [and more about] really developing relationships with Black designers, Black people who are working in PR, and Black people in magazines. [I talked] to them about their experiences in the industry and had so many, if not all of them, tell me, “Nobody’s asked me this.” I didn’t think they were going to go on the record saying it at that time period because it was still taboo to say it. We say it a lot now, but it was still, like, “If I say something, am I going to lose my job, am I going to lose opportunities?” But I was just doing it for grad school to develop data. I appreciate them to this day for being so candid and honest, because it really shaped my thinking and experiences in the industry. That was me really sinking my teeth into what it looks like to do this type of research.

My dissertation now looks at the way that Black people work through death through textiles and clothing, and mourn and perform mourning through clothing. And that comes from a personal experience of losing my godmother a month after I graduated from Parsons. Now that I’m in a Ph.D. program at Northwestern, [I’m] also thinking about the way that death is studied and theorized in the field of Black Studies, and what happens if we turn our attention to textiles and clothing. How might we get different affective experiences like joy or intimacy? What does it mean to turn our attention to this topic that has been studied a great deal, and think about it a bit differently or from a different viewpoint?

rs: Wow, thank you. I love the approach of clothing as an intimate way to enter. The body becomes so much closer than if you’re studying it at a distance.

RB: And it becomes personal, right? That’s what I want to get close to with my dissertation. Yes, we need to deal with a lot of the conversations around Black death. We need to deal with the way that it is a spectacle. We need to deal with the way that it is commodified. Something I’m looking at is Rest In Peace t-shirts in conversation with t-shirts that have been popularized during Black Lives Matter protests, and thinking about whether or not that closeness is the same. I’m thinking about the fact that all of them are sold, even the Rest In Peace t-shirts, and so they’re commodities if we’re thinking about it in a quite literal sense. I’m interested in getting messy and playing with that tension, and I think the overarching impetus is because of my personal experience.

My godmom passed, [and I] inherited her clothes and [wear] some of [them] — this is a part of my grieving process. People always talk about [her] coat and I say the same thing all the time. I didn’t even realize how that was me making sure that people knew who she was and me practicing a citational practice. Like, it’s not mine, it’s my godmom’s, and this is who she was. I was like, whoa, this object I wear on my body has really aided me in moving through my own mourning process and my own grieving process. So I’m interested in getting closer to that. I’m in the early stages of the project, but at present, I want to think about people who lose a grandparent or a friend that might not be in the media and might not cause a movement. I read a lot of media articles on Rest in Peace t-shirts, and one thing that people say is, “It’s like we’re keeping them alive, it’s like we’re giving them a second chance at life,” because it’s actually a photograph of them on their body. They get to move around in the world and almost give this person a certain level of movement and a certain level of visibility. And it probably invites them to have a conversation where they get to talk about that person differently than if they would have maybe appeared in the media or how they are remembered in certain reports. Those are the things that I’m really trying to attend to in the project.

rs: A partner of mine died my last year of undergrad, and wearing her clothes can be so difficult, knowing that she hasn’t aged alongside me and thinking about where the garment would have gone. This garment is from a particular moment, and I don’t know if she would even still like it. I feel like this is such a big part of my life… like, my partner’s great aunt died, and we both wear her coat around. We’re always like, this is her great aunt’s coat, and that’s why it looks so good, right? It’s not just because it’s a good coat, but it takes up this person’s memory. And when someone compliments you —

RB: — you’re getting a story!

rs: Right! I’d love to see an image of your godmother’s coat.

RB: Yes, I will definitely send you a picture of the coat.

rs: Before this conversation, I didn’t know your mom was a fashion designer.

RB: Yeah, back in St Louis. She made my prom dress. She makes prom dresses for a lot of people, she’s a cool mom.

rs: So is that how you developed your interest in fashion? Did you always know you could be a fashion academic?

RB: My interest in fashion was from her, for sure. But I didn’t know being a fashion academic was a possibility. Before seventh grade, I was just following my peers. I was just like, “I’m going to be a doctor or a lawyer or a ballerina.” I was really invested in ballet. In seventh grade, a teacher came to the school named Shirley LaFlore. She was a poet and taught me that writing could be a career. I really didn’t know at that point that it could be. Once she introduced me to that, my world opened up in a totally new way. By the time I made it to high school, you could be in the school newspaper and yearbook, and I started exploring that. Journalism was right there in front of my face, [and I realized] that that was a career path that I could choose. So that’s what I did.

The fashion part came, though, from watching my mother, my grandmother, and my great grandmother throughout my life — watching them make clothes, or my nana sewing my uniforms to make them fit. Just watching these women really work with clothing and work with textiles — what else was I going to be interested in? It was completely brilliant to me that they could do these things. My mom can come up with her own patterns and make it, and that was incredibly fascinating to me. I was just in love with fashion magazines and once I discovered that journalism could be a career, I was just like, well, I’m going to write about fashion. So I pursued my journalism degree and originally it was to be a big fashion editor at a major fashion magazine, and that was the dream — and some of my friends say, don’t give up the dream, it’s still possible [laughs].

rs: It is!

RB: My senior year of undergrad I was minoring in Black Studies, and so I took this independent study for African American history — and I did not want to take this class. So I am completely and incredibly indebted to Dr. Keona Ervin, who was the professor in 20th century African American history, who took me on for independent study. And she said, “You can write about whatever you want, and your assignment is just to do a research paper.” But it was like 20 pages, and I was like, that’s a lot [laughs]. I didn’t know what to write about. I remember going to the library, and finding Vogue magazines in the stacks. I didn’t even know that was there, and it was a dark college library, and I was like, what is this place? They weren’t how you would see a Vogue magazine at Walgreens or something, they’re in these cloth covered books and they’re really big and heavy. And they went so far back. I was just like, I didn’t even know Vogue was this old, this is incredible! I started pulling them down and I didn’t know what I was looking at. Then something literally hit me. I was just like, “Wait, you haven’t seen a Black woman on the cover of any of the magazines that you’ve been pulling down.” And so I went back to my laptop and I said, well, when did the first Black woman appear on the cover of Vogue magazine? It was 1974, Beverly Johnson. And then I looked for the first Black woman appearing on the cover of any mainstream fashion publication. I took it back to my professor, and she said, go for it.

My professor walked me through the whole research process and I fell in love with research. My professor was like, “You have your question, you have your idea, but what’s the context?” And I would struggle with that; what does she mean by context? So she asked me, “What is going on in this time period that’s causing these Black women to appear on the cover of the magazines?” So thus became the first chapter of my thesis by the time I made it to Parsons. I was looking at the 60s and 70s and saying, “Oh, Black people are saying Black Pride. Black people are saying Black is Beautiful. Black people are saying Black Power.” That’s happening as the fashion industry has for so long [excluded] Black women on the cover of their publications. That’s why it’s so incredible now to see a lot of these conversations because it’s all so cyclical— which is why I pursued a graduate degree. I remember when I finished the paper, Dr. Ervin was like, “Have you ever thought about going to grad school?” And I was like, “Absolutely not!” [laughs] In my mind, I was like, “I am going to New York or Chicago, I’m going to pursue my career in journalism, I’m going to be a fashion journalist or fashion editor.” Like, grad school? What?! I have absolutely no interest in that. And so I took a year off and conversations started to happen about cultural appropriation and the lack of Black models on the runway. I would read the stories and be like, there’s no context. Then I was like, aha! Thank you to that professor; it finally clicked. I know the context, so I’m going to grad school and I’m going to sink my teeth into the context. That’s my career now.

rs: Are you in conversation with Professor Ford?

RB: Of course. I love Tanisha, she is brilliant—her and Monica Miller and Carol Tulloch. They’re incredible. I am just trying to follow in their footsteps the best I know how, and I hope I make them proud. They have really carved out a path. I remember discovering Monica Miller’s book on Black dandyism, Slaves to Fashion. It was one of the few books that I could find on the topic during undergrad. I’m so grateful for her, because it really affirmed me in saying that I can do this work. This is a very serious study that she’s created. Tanisha’s book came out as I was graduating with my master’s degree, and so I was just like, thank you, Black women, for making a way. Thank you so much. We’re able to pursue certain opportunities that we maybe didn’t even know was a possibility. I’ve had those moments going to speak, and people are like, “You can do this? You can teach a whole class on this?” As much as fashion requires and deserves serious study, it’s also very fun.

rs: Yes, it’s within a context! But that context is often what I see most fashion journalism really missing. Like an actual historical, cultural, racial context for the garments and why they matter now. Fashion theory journals still feel dominated by white perspectives and white fashion curators, and obviously I’m a white fashion writer. The Met as this site of “ultimate fashion curation” also feels so white.

RB: In regards to fashion theory, that’s still an area that needs a lot of work. We revert back to Foucault and the old white men who do the “theory stuff” [laughs]. So that’s something that I’m interested in exploring as I’m working on my dissertation. I’m thinking with Christina Sharpe’s wake work theory. She says, “I’ve been thinking of this gathering, this collecting and reading toward a new analytic, as the wake and wake work, and I am interested in plotting, mapping, and collecting the archives of the everyday of Black immanent and imminent death, and in tracking the ways we resist, rupture, and disrupt that immanence and imminence aesthetically and materially.” I’m really honing in on her use of the word “materially” to think about clothing and textiles. That’s my intervention into the field of fashion studies. What happens when we actually draw on scholars who are not the old white men who we always revert to? What happens when we think about Christina Sharpe’s wake work as we’re thinking about mourning, clothing, and attire? How does that allow us to expand the field of fashion studies and costume studies, with the preeminent texts and exhibitions being on European mourning attire, like the Met’s exhibition, “Death Becomes Her?” And I know the exhibition has to have a focus, so I’m not saying that a Rest In Peace t-shirt should have been in the exhibition, but what I am saying is that we get the same result if we rely on the same resources. There are so many archives that are not tapped into enough. There are so many theorists that are not drawn on across the board enough that deserve our attention. Of course, as a Black studies scholar, that’s what I’m thinking of, and perhaps that’s more available to me because I’m in the field. But I don’t think there’s an excuse. I think that you know other fields exist, and so you [should] go and look for those resources and engage those resources fully.

rs: I love that. Sharpe as an origin instead of Foucault.

RB: Sharpe is my starting point. Sure, I just read Freud’s Mourning and Melancholy. My project is about mourning, so I’m going to read that, but I’m still going to start with Sharpe. It’s also about reorienting our view. We come up with different things when we reorient our view. In the field of Black studies, what happens if we reorient our view to start with fashion and textiles, and not use it as an adjunct to something? My project starts there. It’s about looking at these two fields that come into conversation at certain points, certainly, but it’s really about pushing for interventions in both areas. [It’s time to] expand the fashion canon of history as we’re thinking about making fashion education more equitable and inclusive in more ways than just getting Black students and students of color in the door. How are you actually providing them with the resources, financially and otherwise, to thrive and succeed and take care of themselves?

rs: Is that part of why you started the Black Fashion Archive?

RB: Yeah, I would come across a lot of things as I was doing research for other projects that weren’t related to my project, and I wanted to create something that would drop some information publicly and hope that someone might pick it up and do something with it. I also started the Fashion and Race Syllabus with Kimberly Jenkins as a way to share resources with anybody, not just academics. I’m a nerd and one thing that I really like doing is just going on online archives and searching the word “fashion” and seeing what comes up. As you look at fashion exhibitions or fashion archives online or in person, they lack a lot of information about Black people or Black folks’ experiences. And if they do have Black designers, it’s the same ones over and over. So what does it look like to look in places like Jet Magazine, Ebony Magazine, and other Black newspapers and periodicals given that Jet and Ebony and really the whole Johnson Publishing Company that was here in Chicago was the source of culture and news for Black people historically? There’s so much information there about designers who didn’t go on to be Willi Smith or Stephen Burrows. We lose a lot when we don’t attend to these types of sites, ones that aren’t prioritized in other archives. For example, I would imagine that you would see a designer’s name in Jet Magazine, and then as an archivist or a conservator, you’d put resources behind going to see if you can find actual garments by that person. Many of these archives are lacking in that capacity because if you don’t know those names, if you don’t know who those people were, and if you don’t go and look in those places, you won’t have exhibitions that actually represent the breadth of Black design.

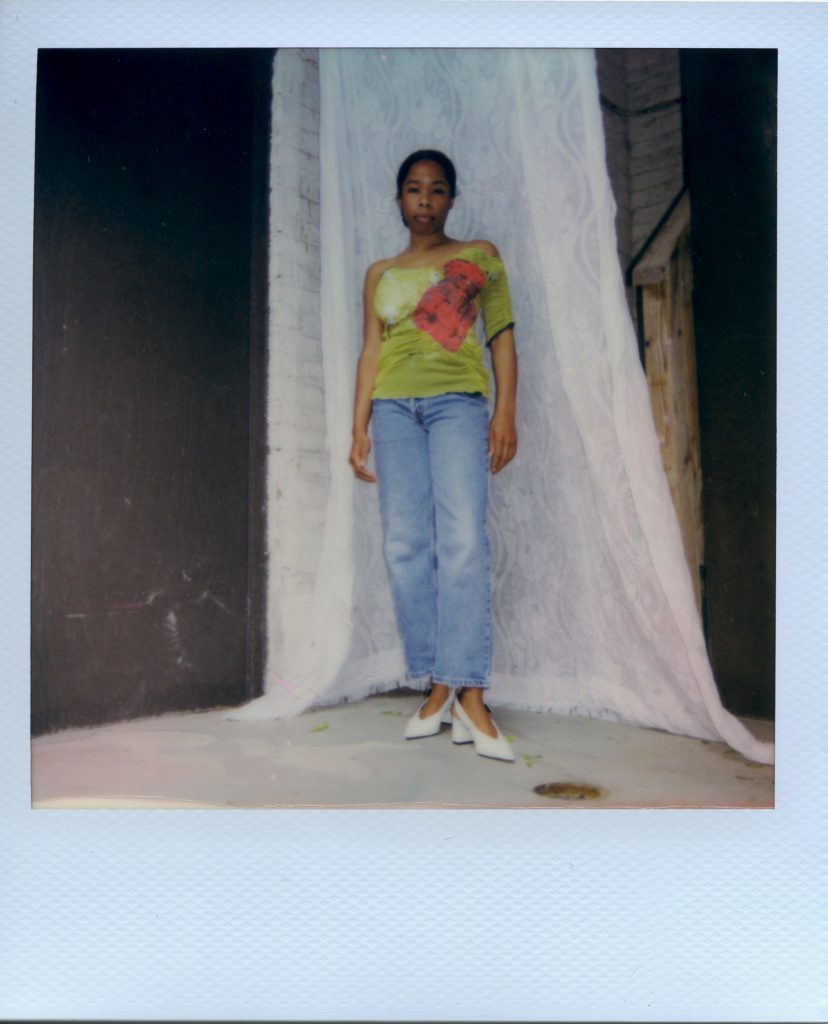

Featured image: A Polaroid photograph of Rikki Byrd sitting on a green couch in her apartment. She wears a dress by Chicago-based designer Adreain Guillory and sits next to a quilt made by her great grandmother. She looks forward directly at the viewer. Styling by row särkelä and Madeleine Le Cesne. Photo by Jared Brown.

row särkelä is an organizer, artist, and white settler raised in tiwaland and living in zhigaagoong. in “fold unfold,” row addresses the seepages between fashion and social movement organizing, surfacing the work of designers and artists who shape and intervene in chicago’s vestiary landscapes. row considers taste to be a political project and investigates how design and dress unfold in relation to local forms of racial capitalism.