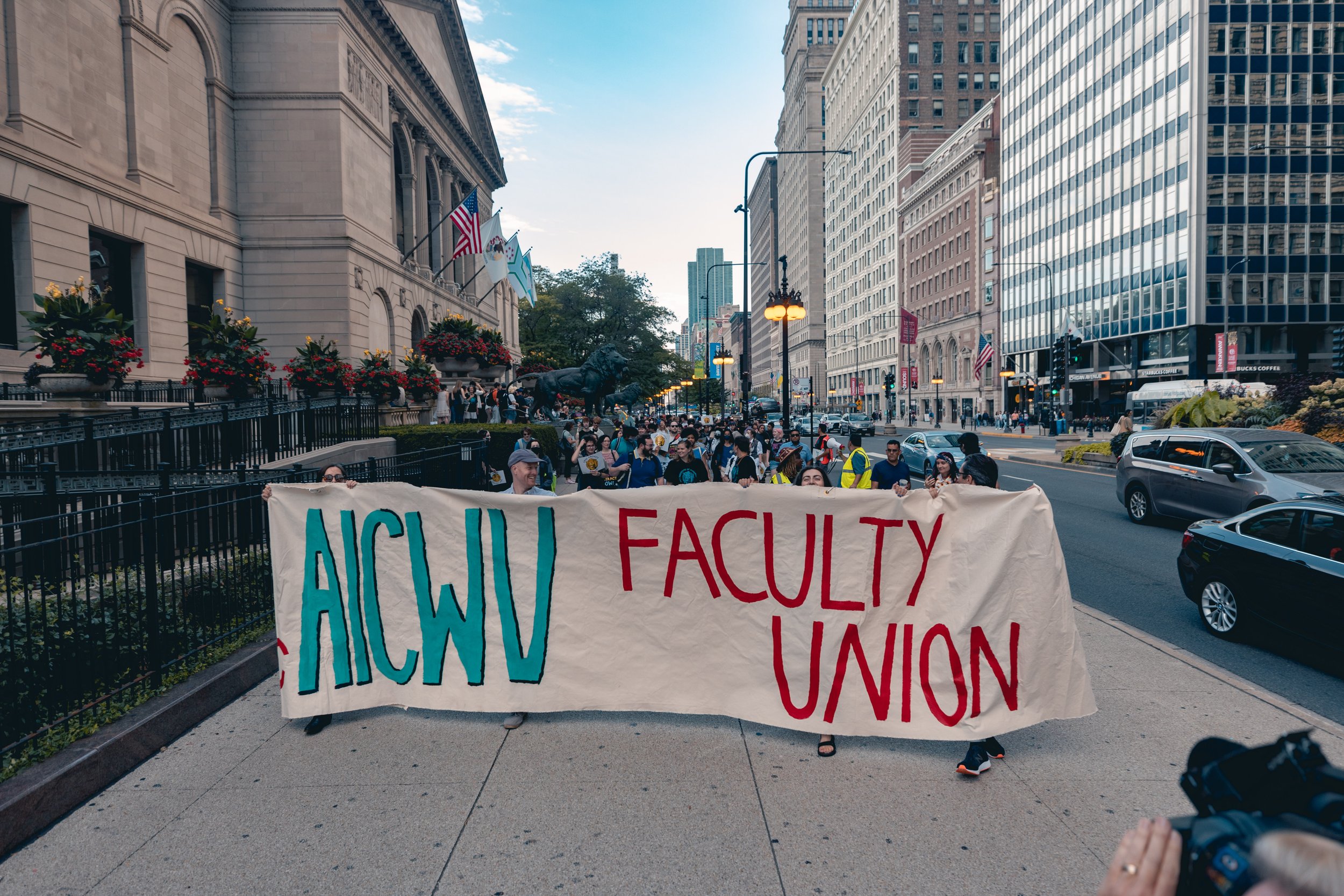

The following is the first in a series of interviews detailing the experiences of non-tenure track faculty at the School of the Art institute of Chicago before and during the fight to both join and expand the newly formed Art Institute of Chicago Workers United. The push for unionization began to accelerate during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Staff at the Art Institute and the School of the Art Institute were the first groups whose unionization was recognized by the National Labor Relations Board and AIC/SAIC administration; a win that occurred in January 2022. The staff of both AIC/SAIC voted to form a single bargaining unit at this time, which is what SAIC’s non-tenure track faculty are now fighting to join.

Since the non-tenure faculty filed for their union election with the National Labor Relations Board September 28th of this year, it is more important than ever to shine a light on the folx whose livelihoods, classrooms, students, families, health care, work, art practices, and very means of survival are affected by the union. Under capitalism, artists and arts practitioners are routinely cordoned off from the material resources, stability, and economic safety to create and teach. This series gives people fighting for dignity on the job, dignity in their work, and dignity as human beings in this world a platform to tell their stories.

Annette LePique: Can you introduce yourself and your relationship to SAIC/AIC to our readers?

Elena Ailes: My name is Elena Ailes. I am an Assistant Professor, Adjunct at SAIC. I teach primarily in Contemporary Practices, which is the freshman foundations program, as well as in the Sculpture department. I have been teaching at SAIC since the fall of 2016; first, just a few classes a year, but now I teach at least 6 classes a year, if not more. I teach at least 3 in the fall semester, and 3 in the spring, and the occasional winter course. I am currently the ‘Part Time Liaison’ for my department, a limited role which acts as a sort of mouthpiece for part-time concerns to the department chair, and to the administration. I also happen to be an alum of SAIC. I earned my MFA in Sculpture here, followed by an MA in Visual Critical Studies.

AL: How would you describe your working conditions?

EA: My working conditions at SAIC have never been very consistent or predictable until very recently. When I first started teaching, I had multiple jobs alongside my work at SAIC. I freelanced as a production artist, worked as an art handler, worked as a writer and editor occasionally, and depended on my at-least-once-a-week bar shift. I never knew if I was going to have a class the next semester or not, and — if so — when, and I was always worried that a change in department leadership would mean I would be forced out. I made myself available to pick up last-minute classes, step in when the department needed faculty to cover in emergencies, and generally just said yes to any opportunity that was presented to me. This led, over time, to more and more courses being offered to me, and I could expect to teach at least a few classes every semester.

Then the pandemic arrived. Like all teachers everywhere, I scrambled to move my studio art classes online, all while navigating new technologies, student’s anxieties, my own anxieties, and my family‘s health. When we returned in the fall of 2020, I returned to mostly teaching in person. The school had implemented a masking and contact tracing policy, and reduced the amount of people who could be in a classroom without actually reducing the number of students who could enroll in a course. Each department dealt with this problem differently, but for some of the classes I taught it meant that half my class met in person while the other half worked asynchronously online, then we would swap over the lunch break — those online would come to class, those already at SAIC would go home. Every demo or lecture I did in person had to be done twice, and I also had to make sure that those working at home or online had guidance and instruction while they worked asynchronously, which meant that I had to organize two lesson plans for each day. Basically double the work, with no increase in my course rate. And, of course, while students had less exposure to people carrying a potentially deadly virus, I still saw everyone and was in the classroom for the entire day.

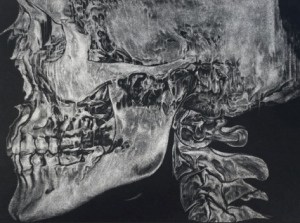

I was promoted from Lecturer to Adjunct in the Fall of 2020, which meant that I had access to employer-provided insurance for the first time in my life, which many, many of my colleagues did not. Many people were teaching in person without access to good health insurance during a global pandemic. Unfortunately, the past two years have seen the promotions process at SAIC grind almost to a halt. There has been a minuscule number of Adjunct positions opened each year for the many, many eligible Lecturers to apply for. Promotion to the Adjunct status is the only way part-time faculty has access to SAIC’s insurance plan; it doesn’t matter how many classes you teach, or how many years you have been employed, or what sort of service you have done for the school.

Even after promotion, and even with teaching a larger than ‘full’ course load, I still don’t make very much money. My partner and I depend on the health insurance we get through SAIC, and my career as an artist wouldn’t be possible without the summers off afforded by the academic schedule (of course, I wouldn’t be able to continue as part-time faculty if I didn’t also maintain my practice as an artist, the very thing that qualifies me as a professional in the field) so it is hard to envision leaving this work for another career. I do think about it all the time, however, and coming up with another plan has felt more pressing during the pandemic.

Oof, last point: adjuncts and lecturers who teach a ‘full-time’ course load at one institution are not eligible for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program that applies to full-time faculty teaching the same course load, in part because of how they are designated ‘part-time’ by their employers. When you are contracted to teach three classes in a semester, which SAIC considers a ‘full load’, the school counts that as 21 hours of labor. Each class is six hours long, and the school allots for three hours of prep for each class, so 9 hours total per course. Unsurprisingly, this accounting does not line up with lived experience. This does not account for the hours and hours that go into writing your syllabi, reading texts, grading and giving student feedback, doing research for lectures, writing those lectures, meeting with students outside of class time, answering emails, etc. It is impossible to do all of those expected tasks every week in only 3 hours. Because the school only credits this full course load as 21 hours, as opposed to more hours or just ‘full-time’ (even though it is equivalent to a full-time faculty’s job description), an adjunct or lecturer teaching a full load is not eligible for PSLF. I’ll tack on a gentle reminder that the price of tuition for an MFA from SAIC currently is $111,600 — not including supplies, fees or living expenses. An MFA is required to teach art at any higher learning institution.

AL: How has or how could the union change those conditions?

EA: First and foremost, our union would be a mechanism for part-time faculty to have a voice when it comes to the conditions of our work. The current mechanism, while well-meaning, does not have the power or leverage we deserve. We have a handful of (wonderful!) elected part-time representatives to a faculty senate that serve in an advisory role only, meaning they do not actually have a vote at the end of the day. Over 75% of the faculty are represented by a position that is constantly undermined and undervalued by the administration, and that have no actual vote when it comes to making decisions.

Having a union will mean that the administration is required by federal law to sit down with empowered representatives of the part-time faculty and to negotiate a living wage for the work that Part-Time Faculty do at SAIC. Each year the administration increases your course rate by like 2% or so, which doesn’t cover ‘typical’ inflation much less the increase in the cost of living that we’ve seen over the last few years. It will mean that we can work towards a fairer and more meaningful benefits structure, which will allow more workers to have access to health care or to save for retirement. And, fundamentally, the union acts as a reminder to both the administration and ourselves that we have value and deserve respect; that body of part-time faculty is made up of brilliant thinkers, creatives and problem solvers with decades of experience.

AL: How does this unionization affect the future of arts work in Chicago?

EA: Our efforts at SAIC are just a small part of a much larger conversation around the value of labor in general, and creative labor specifically. Chicago, like many moments in US labor history, is right at the forefront of that national conversation. This type of organizing is a bit contagious, and I am excited to see how the larger conversation around labor and education has been shifting over the last few years. For example, the part-time faculty union would never have been possible without the incredible groundwork that our staff colleagues at the museum and school forged. We learned so much from their campaign, and they continue [to] be leaders in pushing for positive change at the school.

I do hope that our work is also adding weight to a shifting attitude towards the value of the arts and art workers. Artists and other creative professionals are unique in that our work is both romanticized and completely undervalued, and we are burdened with the myth that we are uniquely suited to suffering and that our love of the work sustains us. But, as Sara Jaffe so succinctly points out in her book Work Won’t Love You Back, love doesn’t pay the bills! I am hopeful that bringing our story to public light helps put some of those old myths to rest, and helps build understanding for folks outside this particular community.

AL: What does the union mean for you?

EA: Something I didn’t expect in the process, and which has been deeply meaningful to me, is getting to know and work alongside more of my colleagues across the school, people I would never have met otherwise. There isn’t traditionally any reason for a sculpture professor to brainstorm solutions with a math professor, and yet that happens all the time here and it is wonderful.

It is also something that I feel I must do as an educator, especially when working at an institution like SAIC. I just can’t square working with students who are taking on a huge personal financial burden to be at a place like SAIC, when I know that the job market that they are being trained for doesn’t appreciate or value their skills, or that there are so few jobs that are sustainable for normal people that vast majority of art graduates go on to do something else. That system needs to change, and if we don’t do it — all of us, together — I’m not sure who will.

About the author: Annette LePique is an arts writer and Lacanian. Her interests include the moving image and jouissance. She has written for Newcity, ArtReview, Chicago Reader, Stillpoint Magazine, Spectator Film Journal, and others. She has a background in dance and music.