Featured image: Jovan C. Speller, “I sat there, Unafraid of the coming night.” Two wooden boards, split in the middle. Across the pair of them is an irregular black blob. On the right hand side, reflective wrinkles of light. In the bottom right hand corner, a seated figure with their back turned to us. Image by Avery Campbell. Courtesy of Aspect/Ratio Gallery.

Imagine, you’re newly dead.

You (the newly dead) have arrived from the world of the living by way of – you can’t quite recall: you remember a dark cloud branching out from the back of your head and you don’t know if it was spilled from your head or if it was being injected. You think you were seated when it happened, but who’s to say? You, the newly dead, are already beginning to lose conscious memories from your previous life. The experience of this makes you thirsty (or maybe you were just thirsty already, maybe you died from dehydration and your body remembers). In any case, you search for water.

The underworld has two rivers. OK, it actually has many but two close by: there’s Styx, (which frankly doesn’t look potable, you’re not sure if you can die again, but why risk it?) Once you’ve looked past the river that everybody knows, you see the clear soft waters of Lethe. You look in and see reeds, sand, silt. You may wade in. As you do you smell something familiar rising from the waters: magnolias maybe if I grab the first thing at hand. And then you cup your hands, dip them in, and sip.

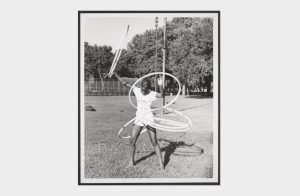

Within the work of Jovan C. Speller, her individual photographs are beautiful, contemplative, and rhythmic, gently pacing your participation in them. In her recent solo exhibition Eulogy at Aspect/Ratio Project, almost all the photos portray flowing water and most contain the floating or wading body of Speller’s stand-in. Speller’s brilliance comes from her understanding of a narrative: she cleverly constructs context. Her piece entitled Departure – two components of an accidentally incomplete triptych – displays wetlands, grass, a pier…and on the end of the pier, a collage: the discrete image of a person not of the surrounding photo explicitly, but maybe of the correct photo at a different moment. Speller’s collages casually introduce images, then shrinks and re-introduces them as jetsam in the water. The effect is mysteriously cumulative: sure, no piece stays for too long, but before it goes it slides something into your pocket. “Hold onto this,” the photos say, “it will be necessary.”

The photos are all verbs: action and motion, no matter what tempo.

Alternately, the artist’s photos that are cast in resin, tactile as they are, ground us on the material plane in nouns instead of verbs. Artifacts, for example, can literally be slipped into your pocket. Jennifer Armetta, the curator of the show, tells me that the whole piece can technically be bought, which includes each individual resin cube – though, so can the independent cubes: a cotton flower, an ancestor’s image, or a memory too opaque to perceive. The cubes can quickly become objects of power, so imbued with recollections as they are. The cotton flower in Artifacts and the seated figure in the collage/mixed media piece I sat there, Unafraid of the coming night both serve as potent souvenirs (that is “to remember,” not a cheap collectible.)

Eulogy ties directly–not as a development necessarily but possibly as a component of a cycle–to Speller’s previous exhibit Relics of Home, which established and re-established Speller’s ancestral farm in North Carolina as a point-of-intersection for all memories: those of intimacy, those of racial trauma, those of something neither-here-nor-there.

Eulogy presents much of that ambiguous Neither-Here-Nor-There, the doors quietly sliding away. After all, eulogy (Greek) is the word for words to send one off to another place, trailing off from this life to another. To get etymological, it’s good speech, an elegy, and what follows sending is a path. Speller’s exhibit is rigorously structured in such a way to either pull us carefully along or to allow us to surface and take a breath for a moment. The subject drifts down one long river from life to death to life to death to life, all the images held together by the right memory in the wrong life. No, the wrong memory in the right life. No, no, the right memory in the right life. I don’t know. It’s a memory that found me and I just can’t recall the whole picture. But it doesn’t matter so much: the river flows regardless of my ability to remember.

As I circle the exhibition space, it occurs to me many times that we don’t always find our way home the first time. Or even the second time.

Lethe, sometimes, destroys. Not in the bad way, but in a manner more like compost. Things are sometimes gone. And that’s good. This is the function of oblivion – opening up and making room for What Else.

Open your eyes. If you don’t, you’ll never know where your body ends and the water begins.

You’re in a river. Your hair is wet. Your belly is cooled by summer breezes. You stand. You’re not sure how you got here, but you’re not a water-dweller by nature so you look around. Your feet deepen their imprints in the sand and you see a shore with trees, driftwood where the water breaks. You’re vigilant not to step onto any of the drift, lest a splinter ruin your moment in the sun. And what a sun: you glance briefly up at the sky, fingers crossed… for what? And why are they crossing? What does that even mean?

You don’t know, but something inside you does. You turn away. You move towards something else.

Persephone Van Ort is a trans, white artist and writer living in colonized Chicago. They are the associate artistic director at the Prop Thtr. Their work has been featured with the Neofuturists, Walkabout Theatre, and others. They write about time, crisis, and dreams. You can find more of their work at jayvanort.com.